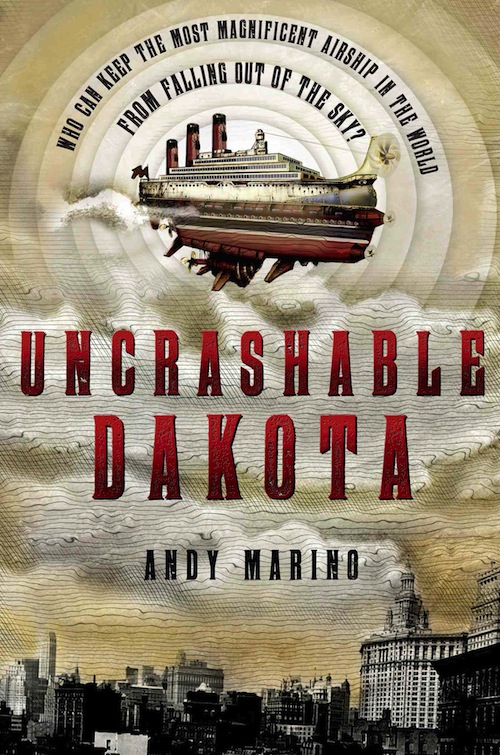

Check out Uncrashable Dakota by Andy Marino, available November 12th from Henry Holt and Co.

In 1862, Union army infantryman Samuel Dakota changed history when he spilled a bottle of pilfered moonshine in the Virginia dirt and stumbled upon the biochemical secret of flight. Not only did the Civil War come to a much quicker close, but Dakota Aeronautics was born.

In 1912, and the titanic Dakota flagship embarks on its maiden flight. But shortly after the journey begins, the airship is hijacked. Fighting to save the ship, the young heir of the Dakota empire, Hollis, along with his brilliant friend Delia and his stepbrother, Rob, are plunged into the midst of a long-simmering family feud. Maybe Samuel’s final secret wasn’t just the tinkering of a madman after all…

Prologue

1909

Hollis Dakota was ten years old when his parents took him to the shipyard that sprawled like a spilled bucket of ash across the river from New York City. His family owned the shipyard, but Hollis had never been there, because he lived in the sky.

The Dakota family business was airships. The yard was their clattering, smoky birthplace. Hollis had seen it from above: a gated compound the size of a city, gridded with factories and littered with the skeletal husks of unfinished ships. He pictured it this way, spread out in his mind like a full-color map, as he followed his parents along a wide gravel road between two hangars. The sulfurous smoke that hung about the yard slithered into his nose. His eyes began to water. He stumbled dizzily behind his parents with rubbery legs and hesitant steps.

He was getting groundsick.

“Whoa!” his father said after a while, as if Hollis and his mother were horses. They stopped walking. They were somewhere in the center of the yard, past the hangars, standing in a vast expanse of packed dirt. Hollis didn’t know why they were here. The whole trip had the winking, secretive air of Christmas morning. His father cleared his throat with a phlegmy rasp and swallowed with a pained grimace.

“You are free to spit in front of me if you must, Wendell,” his mother said. “I’ve seen worse.”

“That was more dust than spit, I’m afraid.” His father used the tip of his finger to balance loose, smudgy spectacles on the bridge of his nose. “Well. Here we are.”

Hollis rubbed the grit from his eyes, and the hazy confusion of his surroundings sharpened into a magnificent scene. He had been led into the heart of a grand excavation: the remains of some prehistoric monster whose rib cage alone would dwarf a whale. Unearthed silver bones curved up to challenge the tall buildings of Manhattan rising out of the fog to the east.

“You see,” his father said, “I want you both to experience firsthand the not-so-humble origins of what will one day be the flagship of the Dakota Aeronautics fleet.”

Not monster bones, Hollis thought. The steel frame of a new airship big enough to carry a Hawaiian island in its belly. He tried not to look disappointed that he wasn’t touring a city-sized fossil.

“Hot rivet!”

Hollis tracked the insistent shout to a scaffold embracing the nearest steel rib. Fifty feet above the ground, a man flung a tiny piece of metal from a steaming brazier. There was an arcing flash, and his partner caught it in a wooden bowl. In a single practiced motion, he extracted it with a pair of tongs, held it against the framework, and answered with a “hot riv-ETT” of his own. Two diminutive figures bearing mallets emerged from a shadowy part of the scaffold, and a quick, brutal bashing took place to drive the rivet in.

“What you’re witnessing up there is the hull in its infancy,” his father said.

Hollis was entranced by the loose-limbed courage of the workers. In less than a minute, they secured four rivets. Their voices rang out in a call-and-answer that harmonized with others up and down the row. Some of the voices sounded like they belonged to women.

Not women, he realized, squinting. Children.

“She’s going to be a real cloud splitter,” his father said. “The perfect combination of luxury and practicality, relaxation and exploration, comfort and luxury. Brought to life by all this productive sweat you can feel in the air.”

Hollis tried to detect moisture.

“I’m just not sure it’s going to be big enough, dear,” his mother said.

His father failed to catch the gentle sarcasm. He unclasped his hands from behind his back and stretched them out straight to either side.

“Darling, I assure you, you’re standing inside the framework of the world’s first metropolis in the sky, with all the familiar diversions and entertainments of Manhattan and space to accommodate enough passengers to rival the population of a modest northeastern town. And the first airship to be positively”—he paused to nod at a gang of passing workmen shouldering long wooden boards, then lowered his voice to a whisper—“uncrashable.”

His mother snorted a single quick hmmph. “Uncrashable?” She shook her head. “That’s a bit cavalier, don’t you think?”

“But, Lucy, you have to remember… ,” his father said, trailing off before he could tell her what it was she had to remember. Hollis considered the word cavalier. It conjured images of charging cavalry horses and puffs of pistol smoke.

“Don’t you but, Lucy, me,” she said. “You know as well as I do where that kind of headstrong attitude landed your father.”

“My father never landed anywhere.”

She put her hands on her hips. “Exactly.”

Chapter 1

On a clear, bright morning in April of 1912, Hollis helped his mother cut the ribbon that hung across the first-class entrance to the Wendell Dakota. It was a two-person job, because the scissors, like the airship, were enormous. One of the silver blades caught the sun and beamed it across the faces of the crowd gathered at the Newark Sky-dock; everybody blinked at once. The blades snapped together. There was a momentary hush as the halves of the ribbon whipped and fluttered in the wind. Then the crowd erupted into cheers. Tall black hats tumbled up into the air along with short-brimmed bowlers and floppy caps.

A pair of earnest young crewmen hopped up on the platform with Hollis and his mother. They took the giant scissors and disappeared, leaving the two Dakotas to wave and grin and bask in the hoots and hollers of the exhilarated crowd. Hollis felt a gentle hand on his shoulder and glanced up at his mother. Without unfreezing her smile, she fanned her face with a few up-and-down waves of her hand and rolled her eyes. Hollis gave a quick nod in agreement. He was sweating right through the fabric of his custom-tailored suit, giving some of the richest people in the world—not to mention their servants, biographers, music instructors, translators, masseuses, and governesses—a fine view of the spreading stains that had already claimed his armpits. And he thought it must be ten times worse for his mother, who was wearing a complicated dress topped with a lace collar that crept up her neck and presented her head to the world like a blossoming rose.

Hollis let his gaze drift across the jostling landscape of passengers waiting to board, their faces flushed and shiny in the heat. Uniformed stewards assigned to each prominent family were scattered about to ensure that no first-class feathers were ruffled by line-cutting or a lack of decorum. Redcapped porters dotted the crowd like cherries on a rich dessert. As high as the roof of a midtown office building, the top of the sky-dock was the first-class rallying point, where the wide gangway transferred passengers to their expansive staterooms in the upper third of the airship. Below them, second-class travelers looked forward to their own wellappointed rooms, while third class would make for shared bunks (men to starboard, women to port). At the bottom of the towering sky-dock, steerage passengers were bound for the holds that surrounded the coal bunkers and boiler rooms.

“I suppose I’ll take a hot day over a stormy one,” Hollis’s mother said, blowing a kiss to some ancient specimen whose pince-nez flashed as he bowed.

“I have to get out of this suit,” Hollis said, resisting the urge to loosen his tie. Using his hand to block the sun, he observed the far edge of the platform where the last passengers were gathered. Beyond them, the blue sky hung empty, and he imagined the clouds had been driven away at his father’s command.

Besdies the crew members readying the ship for launch, Hollis was the first person to climb aboard. It was part of his belated birthday present: he’d turned thirteen last month. He clanked up the ramp from the snipped ribbon to the first-class promenade deck in heavy, steel-lined boots. Every passenger wore them for boarding a Dakota Aeronautics ship so as not to get blown out into the sky by a vicious gust of high-altitude wind. Accidents happened, but the boots kept the blowaway rate to a minimum.

Hollis was greeted at the top of the ramp by Marius Rogers, one of the laborers at the fringes of any given airship’s crew—assisting the chief second-class purser, performing minor plumbing repairs, helping the ship’s librarian stay organized. The joke was that Marius had a secret twin; he always seemed to be in two places at once.

“Morning, Mr. Dakota.” Marius tipped a nonexistent cap by tugging on a lock of his hair. Hollis held out his hand, and they shook. Marius made a face. “You stick that in water?”

“It’s hot out.”

“Oh, come on, now. We’re in New Jersey, not New Guinea. And it’s not even summer.” He dropped Hollis’s hand with exaggerated disgust. Then he stood a little straighter and added a crisp, “Sir.”

“Not you, too,” Hollis said. Lately, crewmen had begun to treat him with an alarming level of professional respect. “Marius, you don’t have to sir me.”

“Better get used to it.”

“Don’t—”

“Sir.”

Hollis sighed. “When did you slink aboard, anyway?” “Been here three days.”

“Shoveling coal?”

Marius laughed. “I doubt the stokers want me anywhere near a furnace.”

Hollis eyed the screw top of a hip flask peeking out of the crewman’s uniform pocket. “I’m glad you caught this assignment.”

“Honest truth, I would’ve booked passage anyway, just for the ride.”

“Maybe next time you’ll get to,” Hollis said. Marius smiled weakly. Concerned that the man had taken this as a threat to his job, Hollis pointed at the screw top. “I don’t care about that.”

Marius shifted his weight, and the flask dropped out of sight. “You know, Mr. Dakota,” he said, “I never seen anything like this ship. Every hair in place. They could load the passengers, give it a shove, and let it fly itself across the Atlantic.”

“It would have to be a pretty big shove.”

Hollis stepped out onto the flat expanse of the first-class promenade deck. The fresh-cut pine planks had been sanded, waxed, and buffed to a glossy sheen. Straight ahead, the overhang of the topmost recreational area—the sundeck (steellined boots required at all times)—sheltered fifty reclining chairs bolted down in a perfect row. In the enticing shade behind them, a hundred round black stools squatted next to a mahogany bar as long as a city block. Unopened bottles of clear and amber liquor, including his grandfather Samuel Dakota’s patented Moonshine Whiskey, were stocked ten feet high along the back of the bar, the small print of their labels reflected in gilded mirrors. Bright little dots of light slid up and down the bottles in time with the gentle bobbing of the docked airship.

Above the bar was the row of glass that defined the starboard edge of Il Bambino’s Restaurant. Its chef had abandoned a thriving career in Florence to create a first-class menu for the Wendell Dakota’s maiden voyage. On his birthday, Hollis had been treated to Il Bambino’s signature dish—braised rabbit on a bed of prunes in a white wine reduction—which he suspected was a punishment disguised as a gift. Skewering the center of the restaurant was the false smokestack, an exact replica of its two functional sisters that loomed over the back half of the sundeck. Each funnel was emblazoned with a black beetle, the logo of Dakota Aeronautics.

Hollis leaned against the rail and craned his neck in the other direction, toward the bow. Both the promenade and sundecks continued unimpeded for a few hundred feet, then began to slope upward, gently at first, then severely, until Hollis’s eyes were following a vertical wall up into the sky, as high as the smokestacks. This was the forward prop tower, built above the nose of the ship to house the turbine that spun the main propeller—the biggest in the world, and Propulsion Weekly’s current centerfold. Only three of the eight steel blades were visible from his vantage point, each the size of a freight-train car.

“I think Mr. Castor is trying to get your attention,” Marius said, pointing toward the dock.

Hollis tore his gaze from the tower. His mother waved up at him. A tall man had joined her on the platform. He put his arms out at his sides, palms up, and cocked his head—the universal gesture for quit messing around and get on with it.

Hollis gave his stepfather a brusque professional nod. He pulled a glass vial from the breast pocket of his suit and dangled it out over the rail. The crowd hushed and watched him expectantly. The christening ritual for a new airship’s maiden voyage was usually performed by one of the company’s board members, but earlier this morning, Hollis had unwrapped a surprise present to find the vial of dirt. He could still hear his mother’s low, serious voice:

Send her off, Hollis. Your father would have wanted you to.

Down on the dock, photographers hid behind black curtains, thumbs crooked over the triggers of their silver flashbulbs. Hollis glanced up at Marius, who said softly, “If you’d like, I can give you a nudge when the wind’s just right.” Hollis took a deep breath. “Thanks, but I think I’m supposed to do it myself.”

A proper airship christening was performed by spilling the dirt out into the sky at the precise moment the wind shifted, scattering it away from the ship. It was bad luck for the dirt to blow back onto the deck, which was why the more experienced members of the aeronautical community generally performed christenings.

Hollis uncorked the vial and closed his eyes against the blinding pops of a few premature flashbulbs. He felt the wind swirl around him. He concentrated, listening hard, trying to plot its meandering course. The glass vial was getting slippery in his sweaty hand.

Don’t rush it, Hollis.

All at once, the wind began to cool the back of his neck. He pictured the dirt scattering above the crowd. He could practically trace the journey of each little particle through the air. It was now or never.

He tipped the vial.

The crowd cheered. He opened his eyes in time to see the dirt float down in a loose spiral away from the side of the airship before vanishing into the sky. He exhaled. Flashbulbs popped. Frantic photographers rushed to pull glass slides from their cameras as assistants replaced the bulbs. His stepfather beamed. Leaping up onto the platform, his stepbrother, Rob Castor, whistled shrilly between two fingers jammed in the corners of his mouth, then doffed his hat to let hair the color of sun-bleached straw whip in the wind.

Marius saluted and returned to his post at the top of the ramp. Hollis put the empty vial back in his pocket, a souvenir of his first christening. When he glanced down to shield his eyes from the extra-bright glare of a flashbulb surrounded by a white reflecting umbrella, his breath caught in his throat.

A tiny pile of dirt sat atop the otherwise spotless railing, a smudge that hadn’t been carried out into the sky.

He told himself that it could have come from somewhere else. A bit of debris that fell from the prop tower. Ash from a crewman’s cigarette. But he knew that every inch of the ship had been scrubbed, spit-shined, and polished for today’s maiden send-off.

It had to be dirt from the vial.

Hollis leaned his elbows casually against the rail as if he were taking one last look across the dock and nudged the dirt with his sleeve to brush it over the edge. He strained his eyes to make sure every last speck blew away, but such a tiny bit was lost as soon as it hit the swirling air.

Chapter 2

“Hey, Dakota!”

When Rob Castor yelled his name, Hollis had already been at the entrance with his mother for an hour, greeting the first-class passengers as they clanked on deck. To distract himself from the secret little smudge of dirt that darkened his thoughts, Hollis was keeping a tally of the old society ladies who insisted upon treating him like the cutest baby in the world. So far he’d endured eleven head pats, seven cheek pinches, and three nightmarish kisses. Now, instead of merely being damp, his clothes were infused with the clashing odors of mothballs and lavender.

“Rob,” he said with relief as the two Castors appeared beside him. At fourteen, Rob stood an inch or two taller than Hollis. Since the day they met nearly three years ago, Rob had always been the heavier one, until a bout of influenza that kept him bedridden on their last voyage aboard the airship Secret Wish had left him gaunt and hollow-eyed. Although he’d been fully recovered for several weeks, his former stockiness seemed to have deserted him for good. Equal parts dapper and shabby, he wore a finely tailored pinstripe suit like his father and a beat-up peaked cap that he hid when he slept so Hollis’s mother couldn’t dispose of it.

“How are the celebrities?” Rob leaned in close. “Pungent, it seems.”

“And never ending. The Countess of Rothes tried to peck off my face.”

“How terrible for you. Heavy lies the crown, eh?”

“I wouldn’t know.”

A pair of yelping Pekingese bounced daintily onboard, their leashes attached to the gloved fist of a fierce-looking old maid trailed by a coterie of pursers bearing luggage. With maniacal insistence, the animals demanded the attention of Hollis’s mother and stepfather.

“Did you hear about our class schedule?” Rob asked.

“I assumed it would be the usual.”

“It is. Except it starts today.”

Hollis’s plastered-on smile wavered. “What do you mean, today?”

“I mean today as in these waking hours we’re currently occupying.”

“We’ve never had classes on launch day before.”

“The Pea’s exercising her authority to hit us where it hurts. She’s been cozying up to Captain Quincy.”

The Pea was Miss Betzengraf, who favored green wool dresses too tight for her short, plump figure. She traveled with the aeronautical families, charged with maintaining a normal schedule of lessons amidst the constant chaos of embarking and disembarking, sky-docking and sky-crossing. A few of their classmates insisted that she was a gypsy from Romania who was constantly placing ancient curses upon her two least favorite students, Hollis Dakota and Rob Castor.

“You know,” Hollis said, his mother’s most recent lecture fresh in his mind, “I think we should try a little harder. Go to some of the classes, at least.”

Rob shot him a squinty sidelong glance, then nodded solemnly. He removed his cap—first undoing the chin strap that kept it from blowing off his head—and held it across his heart. “You speak the sky’s honest truth, Dakota. We haven’t been fair to Miss Betzengraf. We haven’t been fair to our parents. And most of all—”

“I’m not joking. People are starting to take stock of my behavior.”

Now Hollis was quoting his mother directly. Rob arranged his face into a droopy mask of sadness and regret, wiped an invisible tear from his eye, and flung it down to the deck with a dramatic flourish. “We haven’t been fair to ourselves.”

There was a riot of blue and gold as an army of porters rushed past with luggage carts and began dismantling a teetering pile of trunks and boxes dragged aboard by five weary attendants. The dogs transferred their affections to a peacock-feathered handbag. Hollis’s mother and stepfather stiffened their postures. She straightened her dress while he smoothed his necktie.

“Behold,” Rob whispered. “His lordship and the lady Sir Edmund Juniper!”

The Junipers appeared in the shadow of their suitcase mountain. Edmund Juniper was the fourth-richest man in the world and was dressed, as always, like the avid golfer he most certainly was not. (He simply preferred the “fashions of the links.”) Hollis had seen him decked out in plaid shorts for stuffy, unbearable dinners where all the other men wore tuxedos. He also refused to wear sky-boots on the exposed decks, which used to make Hollis’s father agitated, forcing him to fix his spectacles several times a minute. Edmund hailed from an old New York real estate family (the lordship was Rob’s invention) and, as far as Hollis could tell, didn’t do anything except spend his family’s money. According to Rob, this money was very old and arranged in piles.

Edmund strutted over to Jefferson Castor and gave him a vigorous handshake. Then he pulled the cigarette from his mouth and handed it to an attendant who had materialized beside him at just the right moment.

“My whole damn body’s shaking like a leaf!” Edmund said happily, stamping his foot on the deck and visibly unnerving Hollis’s mother and stepfather.

“On behalf of Dakota Aeronautics,” his mother began, “I’d like to welcome you—”

“A ship like this gives off electrical vapors,” Edmund explained, taking her hand, “which I can feel in my toes. Have you met my wife?” He groped the air behind him.

Hollis tried to imitate his mother’s professionalism and held his vacant smile. The newest Mrs. Juniper wore a simple dress that looked light and comfortable, unlike the dense, showy garment Hollis’s mother wore. He figured that when you were as rich as the Junipers, you didn’t have anybody left to impress. Maybe that was why Edmund didn’t seem to care what anyone thought of his domestic arrangement. His divorce had been frowned upon, but high-class reputations had survived worse. It was marrying a nineteen-year-old governess that gave his social circle a case of the horrified gasps.

“And you must be young Master Dakota.”

Mrs. Juniper was standing before him, offering an alarmingly pale hand which dangled at the end of her arm, palm down. Was he supposed to kiss it? She smelled like honeysuckle and had very white teeth. It occurred to Hollis that she was only six years his senior. And married to a stout old man.

“I am the… young master,” he agreed—at the same time wanting desperately to kick himself. Young master, Hollis? Really?

He could sense Rob’s internal quiver as his stepbrother stifled laughter. And suddenly Rob’s hand was holding Mrs. Juniper’s as he brought it to his lips and kissed it gently.

“Clarissa Juniper,” she said. When Edmund turned to collect her, she gave Hollis a small bow. “We are very much looking forward to spending time on your uncrashable ship.

It’s all anyone is talking about.” The newlyweds walked off, arm in arm.

“I hadn’t realized it was your ship,” Rob said.

“Oh, shut up.”

“Whatever the young master wishes.”

Rob nodded at a hawklike patrician thudding his cane along the deck with every step. Hollis scoured his brain for the man’s identity. His mother gave him little pop quizzes from time to time, as it would soon be his job to know every important passenger by his or her face.

“Colonel something-or-other,” Hollis said.

“General,” Rob corrected. “Swallowtail Ovaltine the Fourth.”

Making up first-class names was a reliable source of launch-day entertainment, but right now Hollis was vaguely annoyed that he couldn’t think of the man’s actual title. Behind the colonel/general with the percussive cane, a plump little boy was showing a sweat-drenched steward a card trick. The steward pulled a card from a fanned-out deck. The boy screwed up his face, bit his lip, and closed his eyes. Finally he exclaimed, “Three of diamonds!”

The steward reluctantly turned the card toward the boy and said, “So close, sir—king of hearts. I’m sure that was your next guess.”

“It was!” the boy said, snatching the card. “You threw me off, that’s all.”

“You are a wonderful and mysterious magician, sir,” the steward said wearily.

“I know.” The boy handed the steward the pile of cards in his hand. “Please arrange these carefully on my night table.”

“Yes, sir.” The steward sighed and clicked his heels together before pocketing the cards and rushing off to attend to the boy’s parents.

“He really does seem like a wonderful magician, that one,” Rob said.

“The true young master of this voyage,” Hollis agreed. “So what time’s our first class supposed to be?”

“Dakota, you can’t be serious.”

“I am serious. Except… ”

“Ah. I knew you’d come around.”

“We do have to meet up with Delia.”

“Delia!” Rob exclaimed, as if he’d just now remembered the name of their friend. “So I’m not worth it, but when Delia enters the picture, you’ve once again conveniently forgotten the location of the classroom.”

“I have that stuff she wanted me to bring her,” Hollis said.

“What stuff?”

“Electrics. Wires. Junk. I don’t know.”

“For a bomb.”

“Not for a bomb, Rob.”

“She’s an anarchist. I always suspected.”

“She is not. She’s just, you know, Delia.”

“Either way,” Rob said. “It’s yes sir, no sir until after lunch, right? All Ps and Qs. Then we accidentally get lost on the way to lessons.”

An immaculately groomed hound sniffed its way across the deck, clearing the lane for a young couple and their twin daughters. Dr. and Mrs. Jacob Wellspring. Hollis was proud of himself for the speed of his face-to-name association. And their children… but before he could think of the girls’ names, his mother was calling out, “Junie! Jessie! How wonderful of you to join us!”

One of the girls ran over and curtsied. Hollis watched his mother oooh and ahhh at the stupid bow in Junie or Jessie’s hair, air-kiss her pudgy cheeks, and make a theatrical fuss over how pretty and grown-up she looked. Jefferson Castor beamed, placing a hand on his wife’s waist. Their eyes met. Hollis was struck by something he had never considered: his mother could be planning to have a child with Castor. A new baby to unite their fractured families. His collar suddenly felt like it was choking him. He took a deep breath and tried to reassure himself. She’s still Lucy Dakota. She kept my father’s name.

The other twin hung back, making some kind of inscrutable face.

“She looks like a little schemer,” Rob said.

The girl pulled a toy pig from her pocket and twisted its curlicue tail until a tinny melody filled the air: “Pop Goes the Weasel.”

Hollis shuddered inwardly. He didn’t like that toy one bit, although he would have been hard-pressed to explain why. Voices of the boarding passengers seemed to rise in pitch, an onslaught of nonsense syllables grating against his nerves.

“You ever seen a mulberry bush?” Rob asked.

Hollis and the little girl locked eyes for a moment.

“I wish she’d quit it with that pig.”

Later, as the sun crept past its highest point, the boarding ramps were withdrawn into the empty sky-dock. Hollis watched the last of the first-class passengers—a group of single men who’d made a big show of waiting until women, elderly folks, and families were aboard—cross the deck and disappear down the Grand Staircase beyond the bar. From there, they would disperse into a labyrinth of thickly carpeted corridors and funnel into their staterooms, where they would remain until the ship had safely launched.

Hollis and Rob followed their parents through the shade of the overhanging sundeck in time to see the final passenger make his way down, ushered by a patient steward. They rested for a moment, silently basking in the splendor of the Grand Staircase, which had been designed to evoke the sumptuous interior of an Italian prince’s villa. De’Medici, Hollis thought. Or maybe da Vinci. His brain was scrambled from the day’s forced chatter. It was a prince who favored solid gold, at any rate—the railings alone looked as if they weighed several tons. Hollis wiped his forehead with his sleeve. Jefferson Castor mopped his with a monogrammed handkerchief.

“One of these days, I’m going to hire a substitute family to stand in for us as the welcoming committee,” Jefferson said. “We’ll put out an advertisement for look-alikes, or some such. One more clammy handshake from a perfect stranger, and I’ll abandon ship.”

Hollis almost chimed in—same here!—but caught himself before he could give his stepfather the satisfaction of a shared moment.

“You were positively charming, Jeff,” Hollis’s mother said as she collapsed into a bulky, overstuffed sofa that reminded Hollis of Miss Betzengraf. “The passengers value the personal touch.” She nodded at Hollis. “On the other hand, you looked like you were ready to stick your head in the propeller.”

Jefferson knelt and helped his wife pull off her steellined boots. He placed them in a cubbyhole beneath the sofa and retrieved a pair of soft white slippers, then waited until she’d curled and cracked her toes before sliding them onto her feet.

“Thank you kindly.”

Jefferson stood and rested his long fingers on his son’s shoulder. “Rob, give me a hand with a bit of last-minute scheduling, and we can watch the launch from my office.”

“Top flight,” Rob said without much enthusiasm.

“Or the prop tower,” Jefferson offered.

Rob shrugged. His father was chief operating officer, which mostly seemed to involve writing letters, reading contracts for supply shipments, and handing envelopes to people. To Hollis and Rob, this was scarcely more exciting than one of the Pea’s droning lectures.

“Catch up later,” Rob said. Hollis joined him in studying the frescoed walls that lined the staircase while their parents kissed good-bye. Then he watched Rob and Jefferson get smaller as they crossed the deck.

Hollis’s mother took him by the elbow. “Now you may join the lady on the bridge.”

Hollis was speechless. No one but his mother, the captain, and the navigational officers were allowed on the bridge. Supposedly not even Jefferson Castor, although Hollis didn’t know of a crewman who would stop him. The bridge was crammed with the sensitive machinery that stabilized the ship, along with the eighty-phone switchboard that connected the flight crew with the propeller technicians in the tower and the lift engineers belowdecks.

Hollis tried to make words come out of his mouth. “Bridge… ,” he managed. “Here? The ship’s bridge?”

“Well I’m not referring to the architectural marvel in Brooklyn,” his mother said. “Unless you’d rather spend the afternoon in the stateroom, helping the maid dust the drapery.”

“The bridge,” Hollis said one more time. He’d just bungled the simple act of tilting a vial of dirt. Maybe the delicate nerve center of the ship wasn’t the best place for him to be. But his mother laughed and handed him a pair of shiny black shoes. Of course he was going to the bridge. She’d have him examined by some Austrian head doctor if he refused. And despite his nerves, Hollis wanted more than anything else in the world to see the bridge of the Wendell Dakota.

He yanked off his boots so fast he almost removed his feet at the ankles, then laced up his shoes with trembling fingers.

“There’s something I want to make very clear first,” his mother said. “You have Miss Betzengraf at three. If I find out that you’ve skipped lessons again, I’ll hire her as your personal tutor, and you’ll spend all day in her stateroom, conjugating Latin verbs until we dock in Southampton. I don’t care what Rob Castor does—you’re a Dakota. You have to think for yourself sometimes, you know.”

Uncrashable Dakota © Andy Marino