This week, Saga Press releases a gorgeous new omnibus edition of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Books of Earthsea, illustrated by Charles Vess, in celebration of A Wizard of Earthsea‘s 50th anniversary. In honor of that anniversary, this week we’re running a different look at Earthsea each day!

When I heard Ursula K. Le Guin had died, I wept.

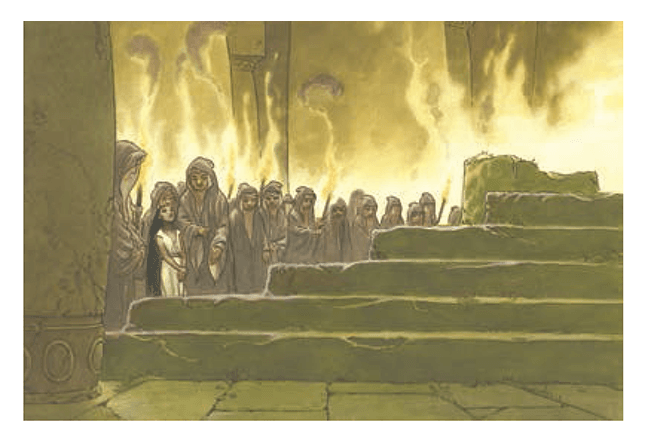

The first Ursula K. Le Guin story I ever read was The Tombs of Atuan. Now, I can’t tell you why I read The Tombs of Atuan before I read A Wizard of Earthsea, only that I first encountered the book when I was ten years old. I’d been graced with one of those precious and glorious class periods where we were encouraged to go to the school library and do nothing but read. The librarian at my elementary school recommended I watch a special View-Master reel for The Tombs of Atuan, truncated and highly edited, but paired with illustrations. (This was before personal computers, people. I know.) I promptly checked out the actual book and read that instead.

I hadn’t yet read the first book in the series, which I know because that book bore a dragon on the cover. Since I was contractually obligated to read any book with a dragon on the cover immediately, it follows the library must not have owned a copy. I would meet Ged for the first time through Tenar’s eyes, through her perspectives on his villainy and later, on his promise of redemption and hope.

Please believe me when I say I was never the same again.

The obvious: I drew labyrinths the rest of that year, unknowingly committing both my first act of fan art and my first act of world building. Every day, obsessively, sketched on precious graph paper in math class, in English, in history—every day a different permutation of Tenar’s treacherous, mysterious maze dedicated to nameless gods. Endlessly varied and repeated, I mapped the unknowable. (That love of mapping and defining the edges of the imagination has stayed with me all my life, too.)

The less obvious: I was always a voracious reader of fairy tales and fantasy stories, but it had never once occurred to me to question the role girls played in the books I loved. Never mind that they were seldom the protagonists: what had slipped my attention was the way in which they were always role models, shining beacons of goodness and light, carefully placed on lovingly carved pedestals. It was never a Susan or a Lucy who betrayed Aslan for a taste of Turkish delight. Princess Eilonwy never wandered from freehold to freehold, seeking her true vocation in life. These girls were sometimes allowed to be petulant, but nearly always were sweet and nice, to be protected (and in so many of these stories, Chronicles of Narnia excepted, eventually married by the hero once they both reached adulthood). They were never tormented, confused, lonely.

But Tenar was.

Tenar, or Arha, the young priestess of dark gods, She Who Is Eaten, was willful and disobedient, guilt-ridden, and—blasphemously, heretically—often wrong. She had been lied to by her elders, fed on a legacy of hate and power sold to her as righteousness and justice. She was not perfect, and while she was protected, her guardians and rivals also acted as her jailers. She was wonderfully, perfectly unreliable, the drive of the story rising through her own gradual challenging of her beliefs, her heartbreak and outrage at discovering that the adults in her life were hypocrites, just as fallible and mortal as herself. Even Ged. Maybe especially Ged.

Buy the Book

The Books of Earthsea

And it was not Ged’s story. How powerful that idea was! Even as a child I knew it would have been so easy for Le Guin to have written it from Ged’s perspective. After all, he was the one imprisoned, the one striving to defeat the forces of evil. He was the hero, right? And didn’t that make Tenar, responsible for his execution, the villain? Tenar had all the power, literally so, in their relationship; Ged only survives by her sufferance. Telling the story through Tenar’s eyes seemed to break all the rules, the very first time I can remember ever reading a story where compassion and empathy truly seemed to be acts of heroism. Not a girl doing right because she was born gentle and pure of heart, but because she made a conscious choice to defy her culture and beliefs. Tenar lived in a world that wasn’t fair or just, a world where light and dark could exist simultaneously, where something didn’t have to be an either/or. Tenar could discover her gods, the Nameless Ones, really existed just as she also discovered mere existence didn’t make them worthy of worship. She could discover she had power over life and death just as she discovered she had no power over herself. Tenar could help Ged escape the Labyrinth and also contemplate his murder later.

While I would later read from Le Guin’s own words that she considered much of The Tombs of Atuan as an allegory for sex, a physical sexual awakening didn’t seem to be the point. Tenar had grown up in the most bitter sort of isolation—her yearning for intimacy and connection spoke to a deeper need than physical contact. And blessedly, Ged clearly had no interest in a child except to light her way.

I love so many of Le Guin’s books, but this one has a special place in my heart. In all the years since, I have never lost my taste for shadows and labyrinths, for those places in our souls where light and dark mix. If so many of the women in my stories have their dark sides, their fears, their capacities for selfishness and even cruelty, it’s because of Ursula K. Le Guin. It’s because of The Tombs of Atuan.

If I have any regrets, it’s that I never had the opportunity to thank her for the extraordinary impact she’s had on my life. Because of her, I am not afraid of the dark.

The Books of Earthsea omnibus is available October 30th from Saga Press.

Jenn Lyons lives in Atlanta, Georgia with her husband, three cats, and a nearly infinite number of opinions on anything from mythology to the correct way to make a martini. Her debut epic fantasy novel, The Ruin of Kings, is scheduled for release from Tor Books on February 5, 2019.

Jenn Lyons lives in Atlanta, Georgia with her husband, three cats, and a nearly infinite number of opinions on anything from mythology to the correct way to make a martini. Her debut epic fantasy novel, The Ruin of Kings, is scheduled for release from Tor Books on February 5, 2019.