Conversations about WarGames these days tend to focus on things like how ridiculous the idea of a kid hacking into NORAD’s weapon systems is, or the old-school gadgets and hardware, or how it’s dated because of the Cold War stuff, or any number of ultimately superficial and/or misremembered details. This is the problem with movies we haven’t seen in 20 years. This is why rewatching them is great, because it leads to pleasant surprises like WarGames still being awesome.

That wording was chosen very carefully, because there are a number of ways in which WarGames isn’t a “great” movie, and there are indeed a number of ways in which it’s “dumb,” but a brief statement of principle is necessary here: a movie, to be good, needs to make logical and/or emotional sense. If it meets at least one of those standards, it works. Thus, while having some logically preposterous elements and a devil-may-care attitude toward little things like cause and effect, WarGames is still a really terrific thriller, with Matthew Broderick giving by far his best 80s dorklinquent performance as the hacker who almost starts World War III by trying to get his hands on new video games early.

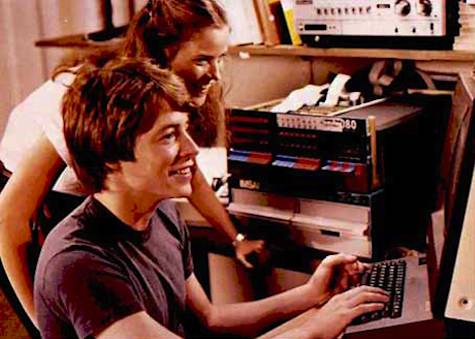

Aside from being a well-made pop movie with an endearing cast (Ally Sheedy is all the adorable, and Dabney Coleman turns in one of his best turns as a harried, grumpy, but ultimately swell professional) and a terrific electronic score, WarGames is a pretty incisive look at just how easy it would be for a number of dumb things to happen and lead to WWIII. We open with a neatly executed sequence leading to the revelation that there is some concern over the possibility of human error impeding America’s ability to defend itself in the event of a nuclear first strike by the Soviets. Dabney Coleman proposes the solution of delegating this responsibility to a computer the size of a room with lots of flashing lights. (Brief aside: the prevalence of actual computers has completely ruined one of the great traditions in movie math, to wit: size + number of flashing lights = computing power.) They do so, but before they can fully secure the network, video game-crazed slacker Matthew Broderick inadvertently hacks into it to impress Ally Sheedy, a noble effort to be sure. Things escalate, to the very brink of Mutually Assured Destruction. People (and computers) need to learn lessons, suspenseful stuff needs to happen, and the movie needs to take a very brave stance against the world being blown up by nuclear bombs. And—spoiler alert—everyone needs to live happily ever after. That’s how these things work.

The thing that really keeps WarGames from getting fatally silly is the sure (and invisible) hand of director John Badham. One doesn’t think of WarGames as virtuoso filmmaking or anything like that, but it’s a lot harder to make something look effortless than one normally thinks, and Badham keeps the focus squarely on things like “Look! Matthew Broderick making grownups look dumb! Awesome!” and “Hey! Ally Sheedy in legwarmers!” and “Dudes, seriously, Dabney Coleman ruled,” and “There is no greater thing in cinema than computers that take up an entire room and have dozens of flashing lights.” The movie’s tight as a drum, and hits all the right buttons right when they need to be hit.

Writers Lawrence Lasker and Walter F. Parkes, to stretch a metaphor excessively, do a good job building the keyboard which allows the above-mentioned buttons to be pushed. There’s a very important balance with a movie like WarGames—as well as Lasker and Parkes’ subsequent and tonally quite similar collaboration Sneakers—between keeping certain things as real as possible so that the wacky stuff and the “well, yeah, some doof who’s flunking biology breaks out of NORAD using a couple random items in the room he’s being locked in, exactly” moments work. One touch that makes the “breaking into the national missile defense system” thing fly is that the way in which Matthew Broderick does so is a lot more in line with the way real hacks are compassed than the typical movie “pound away like crazy on the keyboard while shouting at someone about rerouting the encryptions” buffoonery. He does a little research and then runs a program on his computer that dials every number in a certain exchange in a certain area code, and then goes off for a few hours while the computer runs. Sure, this ends up with Matthew Broderick derping his way into a military mainframe, but the credibility of where it starts gives the flights of fancy sturdy pairs of wings. Also, credibility-wise it helps that the mad scientist is poorly socialized and a little nuts, because, not to speak ill of fellow nerds, but come on.

Really, though, it’s WarGames. The reason we remembered it being awesome is because it is. It wears its age remarkably well for a movie of its type and era, and is the rare Cold War movie that isn’t heavily reliant on archaic context for dramatic resonance. This is because it’s not a movie about the Other, as so many Cold War movies were about The Commies. WarGames is about personal maturity, realizing that yeah, maybe you shouldn’t just hack into any computer because you can; yeah, maybe just because life is transient doesn’t mean letting Earth get nuked to glass is a good idea; and yeah, sometimes the only winning move is not to play. How about a nice game of chess?

Danny Bowes is a New York City-based film critic and blogger.