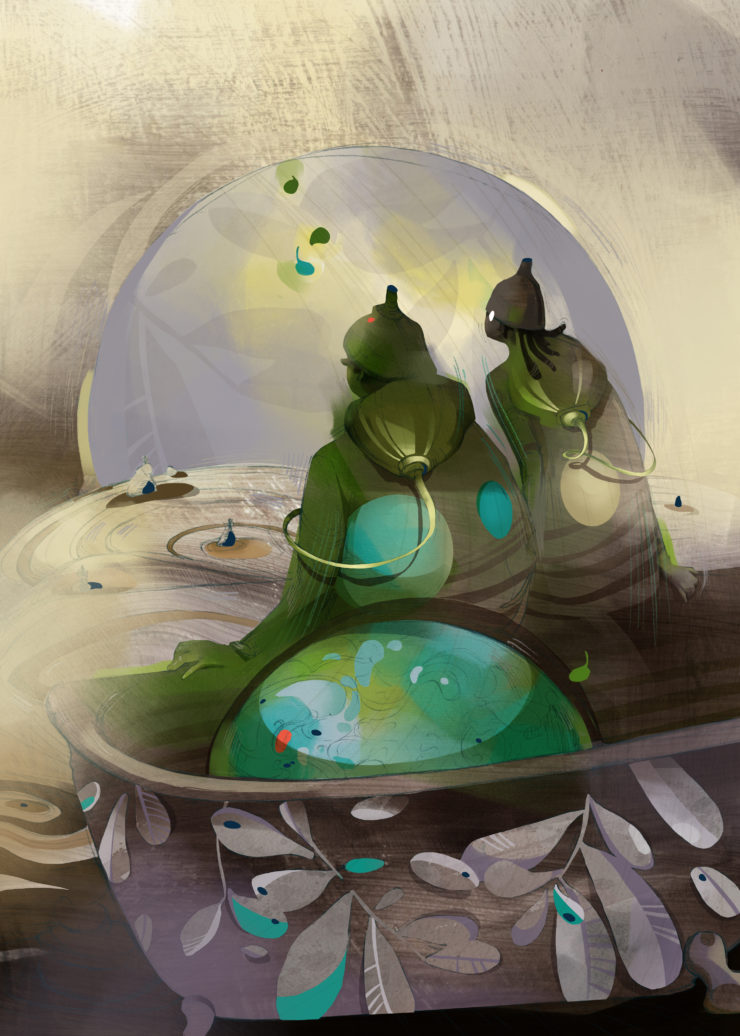

The planet of Quányuán is arid to the point of being uninhabitable. Wetness is a concept left back on Earth. That doesn’t stop one elderly woman from stepping outside the safety of the colony whenever she can for the brief opportunity to fully experience the outside world.

Her bath is deep and steaming. Light falls from the high windows, splashing the marble with wealth. My grandmother has opened these windows a crack, and wet spring air slithers in.

I stand at the edge of her claw-foot bathtub, its rim up to my naked chest, her glasses in my hand. I pull the stems into my fist and rake the lenses through the water, mesmerized by the ripples.

She stands in the other room, undressing. I can see her age-mottled back in the mirror, skin discolored and papery over muscles straight and strong.

She ties up her hair and sings.

Since Adrianna Fang died last year, I’m the oldest one left. I’m supposed to feel sad and alone, maybe, or at least the chill of my looming mortality, but I don’t feel that way at all. Instead, I feel wonderfully unmoored.

I am now the only person in the colony of Isla who has any direct memories of Earth. This means that I can abuse this position at my pleasure and tell them all kinds of bullshit stories they have no way of disputing. It’s my way of getting back at them for the way they treat me now: like some kind of minor god rather than a human being.

It’s my own fault, I guess. It’s what I get for being lucky. Someone like me, who goes outside three or four times a week, ought to have died from cancer by age thirty-five. “Your mutational load is astounding, Marie,” Dr. Davies always tells me, but I have yet to get sick.

I didn’t know I’d stay this lucky, either. I’ve been going outside that often ever since the Rex touched down—before we knew the surveyor probe had made a terrible mistake, and before we realized what this parched atmosphere would do to us. And I kept going outside even after we did know. By then, both Sadie and I had fallen in love with Quányuán’s ferocious desolation, and I figured, well, I’ve got to die sometime, and if I am to die, let it be because I held hands and took nature walks with her.

Buy the Book

Water: A History

When Sadie died, I petitioned the coroner’s office for a cremation. She was Earth-born, too, I argued, and people on Earth don’t recycle the corpses of their loved ones for biomass. But my petition was denied. Her remains were integrated into the community food supply, and now even that pompous asshole Gilberto has part of her inside of him in some way, which I can’t bear to think about.

So when I next went outside, after her remains became thoroughly intermingled with my own chemical compounds, I peed on a rock. Now some of Sadie’s chloride will remain in the wilds of Quányuán, even if her ashes won’t.

Unauthorized atmospheric release of water. They gave me a big fine for that one.

There’s a girl in Isla named Lian. She’s spontaneous, courageous, and kind, and she reminds me so much of Sadie, it makes my heart both ache and sing. I like to imagine a future time when someone will fall for Lian, and she for them, because then something like Sadie and me will be back in the world.

Lian listens to my lies about Earth sometimes. But she isn’t intimidated by my age or position. Most people, when they’re around me and the subject of water comes up, will pause, secretly hoping I’ll offer some revealing anecdote but lacking the nerve to ask. But not Lian. She comes right out with it. “What was Earth like?”

Her directness surprises me out of lying. “Er. Well. The footage pretty much covers it, actually.”

“That’s not what I meant.”

“Mmm,” I agree. “Videos aren’t the same.” I look out the window. I was sitting alone and reading in Lounge Four until Lian came in and politely asked to join me. I could tell she’d sought me out specifically, since nobody else likes to come to Lounge Four to hang out. The room faces the plain instead of the mountains, and the view is nothing but a sea of rock-studded dust for miles and miles. “Let’s see. You’re, what, sixteen?”

“Yes.”

“So that means you did your internship working in the greenhouses last year, is that right?”

“Yes.”

“So you know the smell of soil.” I clear my throat. “Well, Earth was like putting your nose into fresh-watered greenhouse dirt.”

Lian closes her eyes, imagining.

“That dirt smell was everywhere. The whole planet was wet. The oceans tasted like tears, and standing under a waterfall wasn’t like taking a shower. It felt like rocks getting dumped on your head.” Lian laughs. My real stories about Earth are stupid, nothing but a bunch of disjointed details. But Lian nods for me to keep going, so I do.

“You could take walks every day, for as long as you wanted, and never worry. That’s what I miss the most. I lived on the edge of a forest, and my father and I would go walking there, every Sunday morning. He’d tell me all about Earth and all about the stars. It’s part of the same universe, he liked to say, so every part is beautiful and worth knowing about.”

Lian nods, her eyes still closed.

My chest aches for her. Lian will never walk in a forest, not with anyone. “That’s how I got to Quányuán. You had to be eighteen to sign up for the colony ship, unless you came with a parent. My father was one of the engineers who designed the Rex, and the government asked him to go. I could’ve stayed on Earth with my grandmother, but I wouldn’t let him leave without me. I was nine years old.” I shift in my seat, but it’s not that kind of discomfort. “Sorry. I’m rambling. You asked about Earth, not me.”

Lian opens her eyes and smiles.

“Why are you even asking me? Is this for some kind of school project?”

“No,” says Lian. “I just wanted to talk to you. About stuff. Like—I was wondering.” She looks out the window again. “I’ve never . . . I mean how do you . . . do you just go outside?”

I don’t know what she’s asking. “On Earth? Sure. Almost every building is freestanding, and they all have doors that go directly outside. So you—”

“No,” she says. “I mean if I wanted to go outside here. Would I just—do it like you?”

I stare at her. A goofy grin unrolls across her face, revealing gaps in her teeth. Her expression is raw with excitement. “You just . . . go. When you do it. Right?”

I open my mouth. I’ve never been a mom, but a mom-like tirade comes to mind: You can’t just go, you have to save up some money, you have to pay the fee and file for a permit, you have to cover every inch of skin with two rounds of sunscreen, you have to wear long pants and long sleeves and a special hat, and even though I don’t wear gloves, I’m an idiot, so you shouldn’t do what I do. And even I still have to wear a water pack and keep the end of the hose in my mouth so I can sip from it continuously the entire time I’m out there, because while I am an idiot, I don’t have a death wish.

But I say none of this.

Lian turns shy. “I want to know what Quányuán smells like. And I want to feel wind.”

My chest aches again. “Quányuán smells like rock and heat. And wind just feels like a fan.”

“Stories are better than video footage,” says Lian. She looks down at her hands and picks at a hangnail. “But they aren’t the same, either.”

I remember myself at her age, when Sadie and I once pressed our faces against an east-facing window, watching the xenogeologists take soil samples in search of the permafrost and water-rich aquifers our survey probe was so very wrong about. Their newest devil-may-care game was taking off their exosuit helmets to pull in deep lungfuls of alien air. My cheeks grew wet, and when Sadie asked what was wrong, all I could say was, The woods, my woods, I want to go outside and walk in the woods.

Does Lian dream of trees?

My throat is dry, as if I’ve just played a round of the xenogeologists’ game. “Listen,” I say. “If you’ve never been outside before without an exosuit, it’s probably smart if you go with a partner.”

Lian looks up, her face hopeful and eager.

Twelve days later, Lian and I stand together in Airlock Twenty-Three, our water tubes ready in our mouths. Her greasy bare hand is entwined in mine, and my fingers tingle with somebody’s pulse.

It becomes a regular thing.

“Isn’t it heartwarming?” “Isn’t it cute?” “That poor woman—she never had any children, you know, and isn’t it just so nice of Lian to keep her company?”

The gossips in Isla don’t know. Fools. Once again, I’m lucky. If I were fifty years younger—but I’m not. All they see is a lonely old lady and a child who never knew her grandmother. Well, that’s okay, because that’s true, too.

I show her around. The Four Brothers (rock formation), Little Mountain (big rock formation), the Dais (rock formation you can climb on). There isn’t much “around” to show, really, without an exosuit. You can only walk so far in five minutes.

Mostly we sit and look, sipping water between occasional sentences. Lian plays in the dust like a toddler, and sometimes, I join her. We roll pebbles across the Dais. We stack up rocks in the Graveyard, where many walkers, including my past selves, have made rock towers. I point out the ones that Sadie made. Quányuán has no storms to topple them. “This is a game from Earth,” I say, from around my water tube. “I used to make these with my father.”

When three hundred seconds elapse, the issued alarms on our wrists beep, and it’s time to go back. Alone in our rooms, we recover from dehydration, coping with headaches, irritability, and exhaustion. Dr. Davies warns me that I’m way too old for this. Under the guise of argument, I tell her a long and passionate lie about hiking the Appalachian Trail at age fifteen with nothing but a buck knife, a compass, and a half-liter water bottle, but the art is lost on her. Nobody on Quányuán remembers Appalachia.

One day, Lian and I sit on a rock and look north. We’re by Airlock Twenty-One, which is next to the middle school. A handful of kids are crammed against the windows and snickering at us, but I’ll get back at them when the school asks me to speak there on History Day. “I’ve switched my career track,” says Lian.

“Hmm?”

“I’m going to be a miner.”

I smile. “How exciting.”

“Thank god somebody thinks so.” Lian sips her water. “My mom says it’s a waste of my talent.”

“Your mom would do well to remember that if it weren’t for the miners, we’d all be dead.”

“I know, right?” Lian squints north, as if she can see across twenty miles of nothing to the entrance to the nearest ice mine. “And they need people now more than ever. Did you hear about the—”

I wave my hand to both acknowledge and silence. Fifty years of news stories about another depleted subsurface ice vein and everyone on Quányuán someday dying of thirst get tiresome. “You’ll make a great miner,” I say. “And with an exosuit on, you’ll get to stay outside for hours.”

Lian nods and sips. “Have you done it? Taken walks around here in an exosuit? The permit’s much cheaper.”

“I know. And I did, for a while, in the beginning.” I sip, too. “But not for a long time now. It’s not the same.”

Lian smiles around her tube. She reaches down and scoops up a handful of fine, powdery dust. It floats through her fingers like a cloud, staining her palms and making us both laugh and cough by turns. “Not the same at all,” she agrees.

On my next visit to Dr. Davies, a routine follow-up for some labs, she folds her hands and gives me the Look. It’s a funny kind of relief to finally receive it, after waiting so long.

The cancer has come at last.

Damn.

I talk about it at length with Sadie’s nonexistent ghost that night, before we fall asleep. I’m troubled. For over a decade, we had it all planned out: assuming it was cancer, I’d go outside for one final walk, lie down by Sadie’s tallest rock tower (and her chloride), and die a fitting and deliciously romantic death.

But lovestruck notions, while heady, are delicate. The littlest whiff of reality pops them. In my mind, Sadie’s voice points out that, as soon as my wrist alarm went off and failed to show me moving on a homeward trajectory, the Office of Exodus would dispatch a rescue team, and that would be the end of my dramatic gesture.

And then there’s the matter of my nutrient-rich biomass. I’m not as sentimental as I once was, and if I went outside to die, I’d be depriving a number of living people (whom I might not like very much—but that’s beside the point) of my body’s minerals. I’m no heroic ice-miner-to-be, like Lian, and if I’m honest with myself, I haven’t done very much for Isla, either. When I worked, I was a clerk in the city records department; now that I don’t, I tell lies about a planet we cannot return to. The least I can do is not rob my brethren of my literal pound of flesh.

Sadie says it doesn’t matter how I die, because she’ll be with me wherever I go.

I tell her I’m glad.

When she binds up her hair and sings, my grandmother’s voice is clear. Years later, when I recall my childhood on Earth in a jumble of steaming bathwater and golden light, I’ll remember, too, the clarity of her voice, clean and hot like water, deep and pure like water. I swear to god, I’ll go swimming in the north Atlantic at age nine with my cousins, the summer before my father and I board the Rex, and when I look down through that green-glass sea right to the bottom, I will think of her.

Earth is wet. The whole planet is wet, and the oceans taste of tears.

“I’m dying,” I say.

Lian and I are inside, for once, sitting in Greenhouse Eight. The smells of plants envelop us. It’s night, and up above, past whatever complicated synthetic comprises the ceiling, blaze the stars. With no clouds to soften the blow, the night sky of Quányuán is frightening in its intensity and color.

Lian looks at her lap. Her hair falls forward, and I cannot see her face.

“I’m sorry,” I say.

She nods. Her chest moves quickly. “Cancer,” she says.

“I’m not surprised, either.”

Her fists clench and unclench. For a long time, neither of us speaks. I get the grim and heavy feeling that I’ve dicked this up, but how else was I supposed to say it?

“I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to upset you. I mean—I thought you should know. Since you’ve . . . since you’re my friend.” For a moment I feel small and oddly ashamed. Friends with a child? Marie, what are you even doing?

Then one of her clenching hands grabs mine. Away from sterile Quányuán, her fingers are smooth and firm. Mine must feel so revoltingly old to her—fragile and cool, the way my grandmother’s used to feel—but Lian hangs on.

“You’re my friend, too,” she cries.

I feel even worse.

“This is my fault. If I hadn’t found you and asked you about going outside—”

“No no. No no no no. I would’ve kept going out. You know that. Hell, I’m worried about you, going outside so often, so young.”

She wipes her eyes. “I have every right—”

“Then so do I. I knew the risks, I went outside, and here we are. That’s life.”

Lian sniffles and does a terrible job of controlling herself. Sadie says, I love you, but you’re being a selfish old crab right now. About what? I demand, but Sadie only makes that little hissing noise between her teeth.

“Listen. Lian. Don’t. It’ll be fine. Look at me. I’m happy. I got to have plenty of wind and sunshine, and I’ve seen sunrises and I’ve watched the stars come out, and most people in Isla can’t say that. It’s been a good life. I’ve no regrets. Okay, I do regret that I can’t have a spectacular death outside by Sadie’s Tower, but if that’s the only thing wrong, then I can’t complain.”

Lian still won’t look at me. “Can we go outside one last time?”

“Until I’m a pile of bones, my dear, we can go outside as many times as you wish.”

We sit in the Graveyard, facing each other. The rock towers glow, shadowless, from the everywhere-illumination of Quányuán’s night sky. I’m reminded of sitting at the bottom of my cousins’ swimming pool, our legs crossed as we faced each other in pairs, miming sipping from teacups with our pinkies extended. Having a tea party, we called it. Try to make the other person laugh and force them to surface for air before you do.

Lian looks at her alarm. We have 272 seconds.

“I guess this is the closest thing Quányuán has to a forest,” says Lian. “Or at least, the closest thing there is to a forest around here.”

I smile. “Thank you.”

“I mean—”

“I know.”

Sadie leans over to see past my shoulder and through the little sprouts of rock, as though checking to see we weren’t followed out of the airlock. “Are you ready?” Lian asks.

“Hmm?”

She sits back. Her face is very serious, even when she puckers her lips to sip on her water tube. “If you were to die right now. Would you be ready?”

Now I’m the one looking around. “What? Here? Tonight?”

Lian looks uncomfortable. She nods.

“Well, sure,” I say. “It would be as good a time as any, I suppose. Why do you ask?”

She holds out her hand. “Give me your alarm.”

The request seems so banal. I remove it and hand it over, as if she’s asked to inspect a piece of costume jewelry. I’m not sure what’s happening. “What are you doing?”

“I’ll take it inside with me,” she says. “I’ll spend a long time in the airlock, as if we’re standing there talking. By the time I come inside and check in with the Exodus desk . . .” She looks away.

I open my mouth, then close it swiftly around my drinking tube to prevent all that moisture from being sucked away. “Lian—”

“I’ve thought about it,” she says stubbornly. “They won’t do anything to me. They need miners too badly, and you’re old and sick, and I think everyone would secretly be happy if they heard you got to die outside. She died doing what she loved. You know that’s what they’ll say.”

I don’t want to argue. I feel like I have to. “My biomass—”

“—will get picked up later by a rescue squad, so what does it matter?”

I fall silent. I sip at my water tube.

Lian stands, surfacing for air.

I look at her, so smooth and beautiful under the fierce light, my wrist alarm in one clenched hand. Her face melts. “Thank you, Marie,” she whispers.

“Thank you, Lian,” I say.

“I’ll miss you.”

I almost say Me, too, but in a few moments, I won’t be able to miss anything. Not even Sadie. So I just say, “It was a privilege to know you.”

She nods.

Her alarm chirps. Mine chimes in. She turns and moves back to the airlock, so very slowly, weaving in and out among the knee-high towers, as if they really were stupendous trees, each trunk a new horizon.

The airlock yawns open. Gold light splashes over the wasteland. Is swallowed.

Alone in my forest, under Sadie’s tree, I remove the water pack from my back. There’s still about one third left. I hold it above my head with one hand, then I yank out the drinking tube with the other.

I tip my face up to the rain.

Buy the Book

Water: A History

“Water: A History” copyright © 2019 by KJ Kabza

Art copyright © 2019 by Mary Haasdyk