As the great philosophers Aqua once said in their song “Barbie Girl,” “Imagination, life is your creation.” In other words: toys, by being actors on the stage of imagination, can help birth a new reality. While this “creation,” and the life within it, may never leave the realm of the mind, movies offer one arena in which toys can interact, literally and metaphorically, with a greater mythology and have actual, in-universe consequences. Furthermore, because toys can exist both in-narrative and in the hands of viewers, these objects provide a unique opportunity for a story to transcend the screen and extend into the audience’s reality—perhaps even taking with them a bit of the source material’s mythos. And there’s no clearer example of this than one of the single most popular sources of both film and toys in popular culture: the Star Wars franchise.

Star Wars has had a ubiquitous presence in toy aisles for years, and much has been said about the cultural impact of wave after wave of Star Wars action figures, vehicles, and role play toys. But what about the significant presence of the toys we see in the Star Wars universe itself? Let’s consider a sampling of the toys present in the Star Wars films so far—in doing so, I think we’ll find that Star Wars toys mean as much to Star Wars characters as they do to us here in the real world.

In fact, I would argue that watching these characters and stories bestow these objects with such importance has the effect of granting the audience permission to do likewise—in a sense, we are encouraged to view the imaginary world we create by playing with Star Wars action figures and other toys as a potential reality because that is exactly how the characters value their own intratextual toys. We’re simply echoing the behavior we see onscreen…

Luke Skywalker’s Model T-16 Skyhopper

One of the earliest images we see of Luke Skywalker in A New Hope is of him playing with his T-16 Skyhopper model. Though brief, we see him whoosh the toy vessel around through the air as he holds it by a stand attached to the ship’s underside. Through his play, we’re clued into an important aspect of Skywalker’s character: that his passion for flight extends into his imagination. Luke Skywalker not only (allegedly) flies an actual T-16, but imagines himself, or an avatar, flying a Skyhopper on missions perhaps more fantastic than anything available to him on Tatooine. Later in the film, when Skywalker’s impressive piloting ability becomes obvious, we can reference his earlier play as evidence that his role in the film’s climax, piloting an X-Wing down the Death Star trench, could be similar to what he’s imagined himself doing for years. Sure, we also know that the Force is at work there, but something just as great is making itself known, as well: the once-imaginary turned real. In fact, much of the imagery we associate with the use of the Force—closed eyes, hands directing movement through the air—matches the visual cues of imaginary play. Thus, it is no surprise that the film presents the end result of play and the power of the Force in the same breath: the unseen seen. The toys, themselves, are even branded as the “Power of the Force” line, further strengthening this Force/play bond.

In 1996, Kenner released the Skyhopper as a vehicle roughly the size of Luke’s model as part of the “Power of the Force 2” line. This fit a standard 3.75-inch Star Wars action figure, and separated into a smaller craft for added play value. The toy also came with a missile—possibly good for blasting tiny womp rats? This toy invited its owner to engage in the same type of play Skywalker did on screen, and then some. One could both be Luke playing with his toy or control a Luke avatar in an imagined play scenario. Of course, the number of consumers who actually bought this toy thinking it would provide them with the same sort of meaning and foreshadowing of destiny as it did for Luke Skywalker is surely negligible. I convinced my parents to buy me this toy because it was (a) on clearance when I stumbled across it at Kay Bee Toys and (b) probably something I could use in stories with my other toys. This academic redefining and re-reading of the T-16 toy only occurred when I became much older, of course—but once you’ve made the connection between Luke’s on-screen actions and the existence of the toy in the real world, it’s hard to ignore the way that play connects viewers and characters as they engage in the same flights of imagination, mirroring one another in fascinating ways.

Similarly, I’ve also found myself reconsidering the 1999 Power of the Force 2 Commtech Luke Skywalker action figure. This 3.75-inch figure was a miniature Luke Skywalker that came with an even more miniature T-16 accessory that Luke could hold. The figure also “talked” via a Commtech (RFID) chip that connected to a special reader (sold separately!) and offered such choice Skywalker cuts as “What a piece of junk!” and “I’m going full throttle!” Here, one’s play is limited to the third person. Miniature Luke is meant to interact with other miniature characters, not assist the player in becoming an embodiment of Skywalker. This places its own importance on toys, however, as it deems a toy (the T-16 accessory) important enough to exist in smaller-scale play scenarios. Toy companies constantly evaluate and re-evaluate how much of our reality enters the 1:18 scale. In the Star Wars toy universe, lightsabers and laser blasters are permanent fixtures, important elements needed to recreate key moments in the story. By placing a tiny toy representing an actual toy (the Skyhopper model) in the hands of the Luke Skywalker action figure, Hasbro effectively states that this moment of play deserves as much attention as moments of battle. Through the literary value assigned to the toy T-16 in A New Hope, it is clear that both toy and source film understand and celebrate play as a meaningful story element.

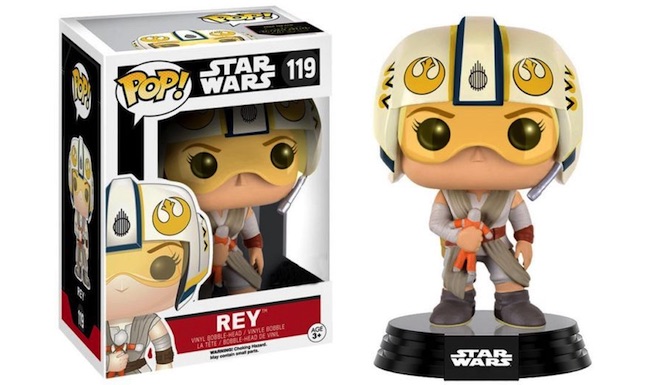

Rey’s Rebel Pilot Doll In The Force Awakens

Just as we see that Luke Skywalker’s moments of play have a particular significance, the same can be said for Rey. At the beginning of The Force Awakens, we see that Rey owns a hand-made Rebel Pilot doll. According to the Star Wars: The Force Awakens Visual Dictionary, Rey made that doll “when she was 10 years old, out of debris she found in the junkfields.” Both the existence and identity of this doll are important.

The doll’s existence shows us that there is a piece of her childhood’s imaginary play realm that she is holding on to. If we’re familiar with the overall plot, we know Rey is able to use the Force. We know that she eventually goes on the journey to find Luke Skywalker, even though she has some initial reservations. What the doll gives us is some insight into Rey’s motivation. Of course she will eventually accept the whimsical mission that is her fate. She has, through the doll, held onto her play even when there was no practical reason to do so. The period of Rey’s life where playfulness was allowed to rule was important enough to preserve by saving a doll for years, even through the hard times that have made her into a survivor. It makes sense that she hasn’t forgotten those moments of openness, imagination, and possibility when she ultimately answers her call to action.

If that’s the only association we’re meant to make, though, then the doll could have been anyone. A standard stick figure would have revealed the same information about Rey’s connection to her childhood. This isn’t an anonymous figure, though. It’s a Rebel pilot. This means that Rey has spent her youth doing exactly what we off-screen fans have been doing: playing in the Star Wars universe. She even has the actual Rebel helmet for cosplay! A common complaint about The Force Awakens rests on its rehashing of the original trilogy’s plot structure. To me, this doll, which is for all intents and purposes a homemade Star Wars action figure, helps to makes that “rehash” work. I connect with it. I’ve been doing the same thing with my Star Wars action figures. I use them to recreate memorable scenes from Episodes 4-6, with my own tweaks. (Maybe Mon Mothma fights the Emperor? Perhaps Dr. Evazan steals Han’s Stormtrooper helmet?) The ultimate fantasy for any child is that these imagined play scenarios, which strongly rely on a foundational text, would come alive and absorb you into their narrative (as it does in movies like The Last Starfighter, pure wish fulfillment brought to cinematic life). For Rey, that fantasy comes true, and it fits perfectly with how I conceptualize this form of play.

Furthermore, it is possible to interpret this toy pilot to be Luke Skywalker himself, as we’ve certainly seen him don that gear many times. If we accept this reading, Rey’s encounter with Luke at the end of the film carries even greater weight. She isn’t just meeting some abstract legend. She’s meeting her hero, her own chosen avatar in the Star Wars fantasy, only now the avatar is real, and she’s as much a character in the story as he is.

This moment also found its way into the toy world through Funko POP!’s 2017 Game Stop exclusive bobble head, which fixes Rey’s doll to her hand (an accessory that echoes the T-16-wielding Luke Skywalker action figure mentioned above). Again, fans are able to bring home a plastic version of Rey frozen while acting out her own fandom. This Funko POP! becomes our entrance into a fantastical universe, its importance justified by its own mold: a character using a doll for the exact same purposes we are.

Jyn Erso’s Stormtrooper In Rogue One

Like both of the previously noted scenes, Jyn Erso’s toy moment also comes early in Rogue One, an introduction to events to come. After she has fled the incoming Death Troopers as a child, we see that she has left behind one of her toys: a Stormtrooper action figure. Around the time of the film’s release, Entertainment Weekly confirmed with the filmmakers that, yes, this is supposed to be “a galactic version of a toy soldier.” This could indicate that Jyn’s toy was not self-made, as Rey’s was. Instead, this miniature Stormtrooper may have been mass-produced—toy propaganda meant to ensure that the Empire would have a strong (presumably positive) presence in the imaginations of children. If this is the case, it would be logical to infer that Galen Erso, Jyn’s father, either purchased this item for her or that she was given it by someone else. This allows us to see the extent to which the Empire has permeated this home. Imaginary play wasn’t an escape, necessarily, for Jyn; it was just yet another place conquered by the Empire. That isn’t to say her play wasn’t fun—it probably was, if she held onto the toy—but it was at least partly defined by the forces she would come to fight.

We can assume Galen’s disillusionment with the Empire became clear to young Jyn on at least a handful of occasions; after all, there was an entire plan of escape in place if the Empire ever came after their family. We don’t know how Jyn engaged with her toy Stormtrooper, but, with this climate of bitterness in the home, one possibility is that the Stormtrooper, through the transformative nature of play, became an agent of liberation—perhaps a savior in disguise. This would pair well with adult Jyn’s infiltration of Scarif, where she has to, essentially, become a “Stormtrooper” (okay, Imperial Deck Technician) in order to steal the Death Star plans. The idea to disguise herself seems logical on its own, but imagine that it’s the actualization of a play scenario she imagined time and again as a child. The presence of her toy allows us to make this leap, and, while it could never be verified by the film, it would locate Jyn’s motivation in the same place as Luke Skywalker’s and (though many years after Jyn’s death) Rey’s: the realization of childhood imaginary play.

Beyond the screen, Stormtrooper action figures are as common as can be. Kenner/Hasbro have produced numerous versions over the years, even excluding the multiple editions of Snowtroopers, Sandtroopers, Spacetroopers, Clone Troopers, Death Troopers, and Scout Troopers also produced. It’s also worth mentioning that Funko POP! preserved Young Jyn and her doll in bobble head form. My favorite, though, is the replica of Jyn Erso’s toy Stormtrooper that ProCoPrint3DProps makes on Etsy. While the licensed action figures are fun, I can’t resist the juxtaposition of a toy that is likely bulk-manufactured in-universe becoming the boutique, hand-crafted doll in our world. Based on the name of the Etsy shop (“Prop” being in the name, not “Toy”) and the price point of this item ($49.50), it’s unlikely that many people are buying this as a toy for their kids, especially when Hasbro’s $6.99 version is available. It’s interesting to think about why these replicas hold such value. I suspect that the answer might lie, at least in part, in the role it plays in the film itself. Jyn had to leave the toy behind—a small, early tragedy in story filled with tragedy and sacrifice. We equate an appreciation of her toy with an appreciation of Jyn herself: the toy becomes a symbol, the embodiment of her otherwise intangible struggle, and, as such, gives us a way to connect with her world. As a fan of the movie, that’s enough motivation for me to count out 4,950 pennies from under my couch cushions.

The Force-Sensitive Children’s Figurines In The Last Jedi

At the time I’m writing this piece, we don’t know much about where we’ll go after the end of The Last Jedi. All we get from the film’s final scene is a group of possibly-all-Force-sensitive kids gathered around a doll while one child narrates a story. Though he does this in a language we can’t understand, we do manage to discern the words, “Luke Skywalker, Jedi Master,” as he puts down a doll. In the Star Wars: The Last Jedi Visual Dictionary, we learn that the storyteller is Oniho Zaya, and he, in fact, owns a “Jedi doll,” an “[AT-AT] Walker toy,” and a “Gangster doll.” The toys all look hand-made, like Rey’s, indicating that, while the characters of the Empire (like Erso’s Stormtrooper) could be manufactured products, Rebel (or Resistance) characters have no place in the official material culture of the galaxy, except in a homemade, underground sense. This means that the act of play is also an act of rebellion. These seemingly now-liberated child slaves are given the power, through toys, to tell a story that was once forbidden, a story that may become their own story, as well.

By placing this toy scene at the end of the film and not at the beginning of the movie (as is more common, and happens in all the Star Wars movies discussed above), The Last Jedi shows us that toys can be more than a starting place. They can also provide an effective ending, communicating hope and possibility, underscoring that a massive, intergalactic struggle was won at great cost so that the next generation may be permitted to re-enter an imaginary realm that was at risk of being closed to them forever. Because we understand toys to be agents of the imagination, they are the logical objects to depict the reopening of this space. Additionally, we receive this message from a group of children that are racially and gender-diverse—representation always matters. How empowering that is, then, for younger viewers who will find their own “Jedi dolls” and use them to tell their own stories?

Indeed, privilege is always a factor in conversations surrounding toys. Whether or not a child can receive an official Star Wars toy depends on a number of financial factors. But The Last Jedi, like The Force Awakens, responds to this issue in an interesting way. In both of these films, the toys are clearly hand-made, offering the possibility that the most meaningful ways into the imagination are through objects you make yourself at a very young age. (In the animated TV series Star Wars: The Clone Wars we see that young Padawans also make their own lightsabers.) I’m not so sure how this message will resonate with most kids who may desire the cool, plastic Obi-Wan on the blister card made by Hasbro over the self-assembled stick-and-cloth Jedi, but I’m also not going to assume the message is lost. I’ve talked to many adults that have incredibly significant connections to the found or homemade objects they played with as children. Perhaps The Last Jedi validates that play most of all, even if Hasbro remains extremely good at marketing.

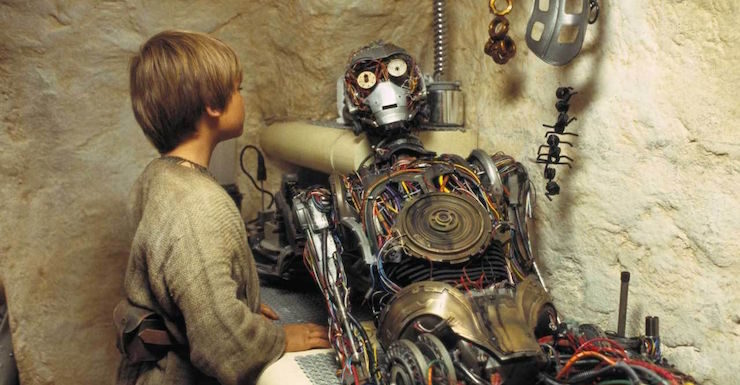

Anakin Skywalker’s Toy In The Phantom Menace

In Episode I: The Phantom Menace, Anakin Skywalker doesn’t engage in the same type of play as the other characters mentioned above. There is no model, doll, or action figure that seems central to his imagination. Instead, he focused on what he has built. One such creation is especially striking, as it looks like a human-sized, autonomous action figure: C-3PO. Not only is C-3PO humanoid in appearance, he interacts with the world in a way that is identifiably human. When Padme meets the droid, she refers to this creation as “he,” and gives every indication that his feelings are just as legitimate as those of a flesh-and-blood person.

The interaction between Anakin and C-3PO sounds a little different, though. While Anakin does claim that C-3PO has been “a great pal,” he also uses predominantly technical language toward him, apologizing for not getting to “finish” the robot and put “coverings” on his exposed circuitry. (Earlier in the film, this conversation is framed as C-3PO being “naked,” but to Anakin he is simply unfinished, an important distinction when thinking about differences between the language assigned to human bodies and the jargon reserved for man-made objects.) It also seems as though C-3PO understands Anakin to be not father or brother but “maker.” Anakin notes that C-3PO could be sold, though he’ll try to make sure his mom doesn’t do that. All of this is evidence that Anakin tends to view C-3PO as more of a large, self-made toy than as an equal.

Since we know Anakin Skywalker becomes Darth Vader, this paints young Anakin’s play in a troubling light. In a universe that clearly has toys accessible to even the poorest characters, Anakin chooses to build a robotic person without granting that creation personhood. Instead, C-3PO can never be anything more than a playful project in the eyes of his creator, easily abandoned when a more interesting opportunity comes along. Anakin’s toys can look like people, and they can be discarded when they no longer serve his purpose. When we consider how Darth Vader treats the people he encounters—Force chokes, lightsaber battles, manipulation—we see his evil as rooted, at least partly, in his play. Here, again, the Force is a factor: Darth Vader has given himself to the Dark Side. But, given that we have seen his version of childhood play, the Dark Side may only exaggerate tendencies that were there from an early age. Anakin doesn’t value his “toy” person, making it less shocking that Anakin fails to value the actual people that will later surround him.

To be clear, this isn’t to say every kid who trashes their toys will turn out to be a some kind of sociopath. Virtually all credible research on play suggests that play itself does not cause violent behavior. Play, regardless of its manifestation (within reason), is an important part of development. However, obsessive behavior (whether it occurs in play or not) that occurs over a long stretch of time can be one of many factors that negatively impact one’s social development. Anakin’s disregard of the human-shaped C-3PO provides interesting metaphorical mileage, but perhaps more disconcerting is the time it must have taken the very young Anakin to build such a complex machine, only to toss him aside on a whim.

Happily, if you buy the 1999 Electronic Toy Talking C-3PO, who talks to you as you build him, there’s no danger of repeating Anakin Skywalker’s path to evil. Hasbro’s C-3PO was built in a factory, probably very quickly, and is presented to you as a toy. You don’t actually build it. Instead, you can “play build” it over the course of roughly ten minutes, take it apart, and put it back together in roughly another ten minutes. Anakin, on the other hand, surely devoted a significant amount of his free time—whatever free time child slavery allowed him—to constructing his droid along with his podracer. Through Anakin’s best friend Kitster, we see that he has socialized somewhat, but questions surrounding his investment in (and ultimate abandonment of) C-3PO leave us wondering whether he was ever able to spend enough time building meaningful bonds with others.

Whether the toys are self-made or mass-produced, Star Wars has a lot to say about play. In all of the above cases, we see that toys are used to indicate two things: how a character’s personality is rooted in past imaginative play, and a foreshadowing of their future arc. When children receive toys, it is common for them to think about how this toy will fit into the imaginary universe they’ve created with all their other toys. (Adult collectors may do this, too, but perhaps some of us are a little pickier about paint applications and bent cards.) Rarely, though, is the toy’s potential role in our futures given any thought. Star Wars, however, allows us to look at a Princess Leia action figure, for example, with new eyes. We get to see her as a member of a galaxy that does not necessarily need to end: It can keep going. You can carry it with you on your own journeys. You can interact with it. You can let its lessons seep into your other reality. You can let her inform your future, the person you become. She can be toy and totem. Imagination is creation, and, as creation, reality. The Star Wars universe believes that there is life in plastic—and, yes, it’s fantastic.

Jonathan Alexandratos is a playwright and essayist who writes about action figures and grief. His edited collection of academic essays on toys, Articulating the Action Figure: Essays on the Toys and Their Messages, is out now from McFarland. Find him on Twitter @jalexan.