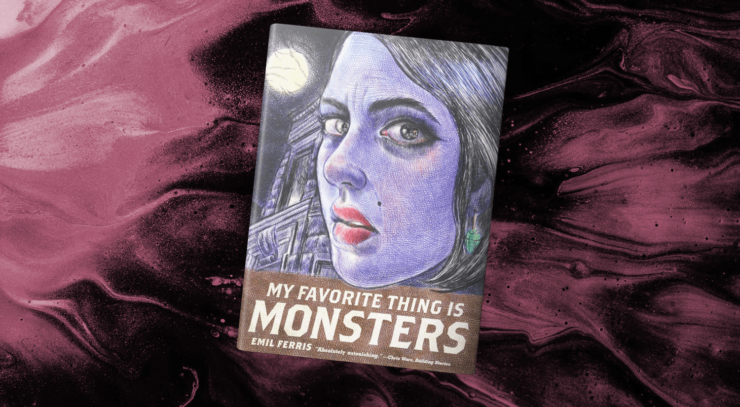

In 2017, Emil Ferris and Fantagraphics published the first volume of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, and I have been waiting for the second volume ever since. It’s not often that you find a graphic novel quite this ambitious: not only does it cross genres and decades, it also explores the ugliness of love and grief and, well, monsters.

In the pages of MFTIM, the year is 1968, and it is a year of transformation. 10-year-old Karen Reyes knows better than anyone that monsters are lurking on every corner of her neighborhood in Uptown Chicago. In writing and illustrating the diary of her life, Karen confides that she wants nothing more than to be bitten by a werewolf or a vampire, to become as powerful and terrifying as the creatures from her brother’s pulpy magazines. When her beautiful neighbor Anka dies, she is convinced something equally sinister is at play—and the more she learns about Anka’s past, the less she has to think about her own crummy life.

It would be easy and cliché to say that Karen learns that humans were the real monsters all along. Kids are smarter than we give them credit for, and so are comics. For all its complicated morality, Karen knows who the bad guys are, whether they’re taking Anka to a camp in 1930s Germany or murdering Martin Luther King Jr. in her own time. But even the good ones are monsters—even Karen’s beloved brother Deeze. Beauty, the grotesque, and the banal coexist in MFTIM—in its visuals, its characters, and in its driving ethos.

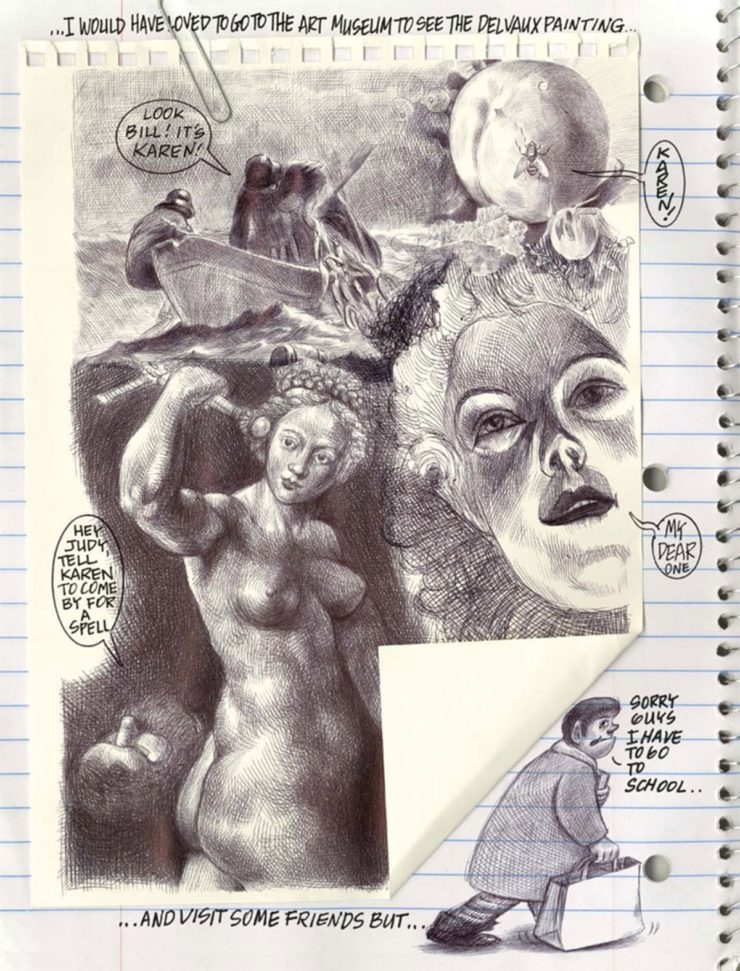

MFTIM messes with our expectations in lots of ways, but its playfulness with genre and form are chief among them. The comic is a queer coming-of-age story, as it follows Karen’s first experiences of grief and realizations that her family is less than perfect. It is a crime noir—complete with trenchcoat, hat, and tape recorder—as Karen devours the mysteries left in the wake of Anka’s death. It is historical fiction, it’s a love story, it’s a pulp-y monster and ghost story rolled into one. Somehow, none of these elements feel disparate—because we’re reading from Karen’s point-of-view, there’s a child’s logic that holds everything together. A painting is never just a painting—it’s a clue to a murder scene. An outsider is never just an outsider—they’re a monster, a ghoul, a protagonist of their own story.

In a sense, that is the ethos of MFTIM: that even the things and people on the fringes are connected to something bigger. Karen often looks to her brother Deeze for explanations of the world, but in one quiet moment of the story, she disagrees with him:

“Deeze says that most things in life aren’t right or wrong. He says there’s not too much black or white. To his eyes most stuff is like pencil shading. Lots of shades of gray. Mama says different. She believes it’s either right or wrong. Me? I think they’re both wrong. For me it’s like in a photograph. You have to look close. It looks like shades of gray, but it’s really lots and lots of tiny dots of inky black on a perfect page of white.”

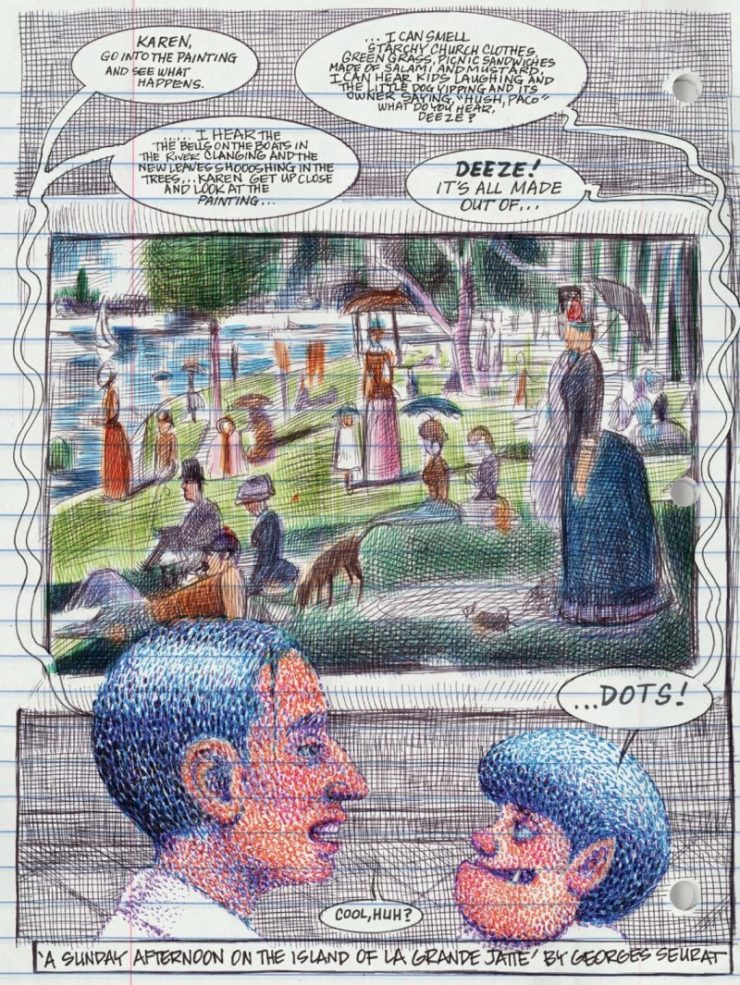

This hearkens back to another scene in the comic where Karen sees A Sunday on La Grande Jatte by Georges Seurat for the first time—the delight and wonder at getting close enough to see the gaps between the dots that compose it, standing far enough way to see how they connect. Neither perspective on its own is the truth; only by looking both ways can anyone appreciate the painting. Only by seeing the beauty and ugliness in people can we see how they’re connected.

The physicality of MFTIM is undeniable, and not just because the visuals mimic these plays on perception: as we witness Karen crawling inside paintings at the Art Institute and talking to their inhabitants, we become tethered to the act of consuming artwork in a whole new way. No longer are we just turning pages, but we’re inhabiting them, just like Karen. We begin to see the world as she does, even seeing her as a little werewolf instead of a girl.

Ferris’ artwork itself is mostly intricate pen and marker, sketchy and cross-hatched but rarely messy. Her style, however, changes depending on Karen’s state of mind or on her allusions to other artwork (there are layers of references to monster movies, pulps, and classic art—all put on the same level, all loved and rendered tenderly). One of the more remarkable stylistic choices, I think, is the use of panels—far more sparing than in your typical graphic novel, and often used to impose order or temporality onto a given scene. Ferris’ style isn’t just functional to the story, it very much is the story.

But that story is still very much incomplete. We still don’t know how Anka died, still don’t know what dark deeds Deeze has committed, or whether Karen will ever truly transform into a monster. By the ending of the first volume, it’s obvious that the second installment will play with our perceptions even more than the first. I’ll be interested to see how, and how in particular those perceptions shape the ways that Karen loves the many monsters in her life.

I adored My Favorite Thing Is Monsters—even more on the second read. I’ve spent the duration of this essay trying to wrap my head around all the many things it’s saying about a little girl that wants to be a monster, but I still have so much left to unpack. With a September 2020 release date for Volume 2, it seems I’ll have plenty of time to keep trying.

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters is available from Fantagraphics.

Buy the Book

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters

Em Nordling reads, writes, and manages research in Louisville, KY.