Dystopias have been written by mainstream writers—they are the form of science fiction mainstream writers are most likely to attempt, and most likely to succeed at. The more I think about this the more I wonder if it makes sense to think of dystopias as a subgenre of science fiction, rather than a mode of mainstream fiction that science fiction writers use from time to time, similar to noir. Dystopia was forged outside of SF, by Huxley and Zamyatin and Orwell. It’s largely been writers outside of SF like Atwood and Levin who have carried it forward. This recent burst of young adult dystopias are mostly written by YA writers and not by SF writers. Dystopias existed when SF was a still very young genre. And when I think of canonical dystopias it tends to be ones by mainstream writers that leap to mind.

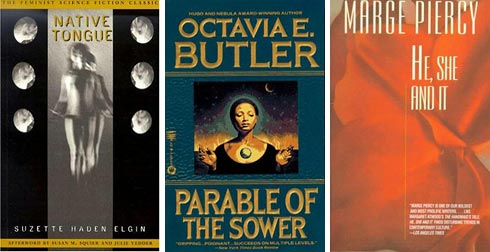

Genres are marketing categories, but genres are also useful ways of thinking about things that are in dialogue with each other. We certainly have dystopias from within SF, like Elgin’s Native Tongue or Butler’s Parable of the Sower, but we also have SF noir and SF mysteries and SF romances. Science fiction writers are adept at taking mainstream modes and taking them into SF.

Does it make sense to look at something like Piercy’s Body of Glass (aka He, She and It) or Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go (post) in a science fiction context? They are certainly “set in the future” but that isn’t a very useful way of looking at things. There’s a worldbuilding thing that science fiction does that they mostly don’t do because they’re more interested in doing a mainstream thing, and if you look at them as SF you start saying they don’t make sense from angles that their authors haven’t even considered because that’s not what they’re interested in. Never Let Me Go suffers if you compare it to Cyteen (post) because while Ishiguro has done the social extrapolation he doesn’t really understand the science of cloning. But if you compare it to his other work, and to Ian MacEwan and Vikram Seth and other contemporary mainstream writers you can see much more interesting connections. On the other hand, Cyteen is inarguably in dialogue with Brave New World.

I’ve argued before that science fiction isn’t a genre in the “set of tropes” “fears pool” sense, while it absolutely is in the reading protocols sense. Dystopias are definitely a genre in that first sense. They take a current fear and push it hard to come out with a world where everything is as bad as the writer can imagine. They have a shape of story, in which somebody accepts their world as the way the world is and then comes to reconsider, question and learn deeper truths about it, and then attempt to change it. The attempt can go well or badly, and the more the book is part of SF, where worlds are characters and more likely to change, the more likely it is to end well. But they mostly don’t require SF reading protocols. And they are mostly in dialogue with the news and literary fiction rather than with current SF.

Dystopias are certainly doing “what if,” which ought to make them SF. But it tends to be what if one thing only carried to the worst excess, rather than a more science fictional complexity. It’s interesting that Le Guin wrote an “ambiguous utopia” and Delany an “ambiguous heterotopia.” Science fiction tends to be more nuanced and ambiguous in this area, and to have more things in it that are there because they’re cool and not just to serve the theme. Mainstream writers writing utopias and dystopias tend to be warning or preaching, or using what they’re doing as metaphor for talking about something else.

But maybe this is the wrong question. Dystopias aren’t really either firmly within SF or firmly within mainstream. Maybe they are best seen as an encapsulated subgenre on an uneasy border, their own thing? Or is this too utopian a suggestion?

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.