“Why isn’t Greg Egan a superstar?” Jon Evans tackled this question on Tor.com in 2008. More than a decade later, perhaps the relevant question is: “Why isn’t Greg Egan’s fiction getting film or TV adaptations?” Egan’s body of work is seminal and canonical; he is the author of award-winning and cutting-edge science fiction that could easily be the basis for eye-popping and thought-provoking adaptations into other media.

To begin with, Egan’s short story “Glory” (2007), with its adrenaline-inducing battle finale, has a similar feel to an episode of The Expanse (2015-present) and could be just as visually thrilling. And “Luminous” (1995) with its sequel “Dark Integers” (2007) would make an exciting premise for radio or film adaptation. If you thought the surgical “birth” scene in Ridley Scott’s Prometheus (2012) was scary, you might find the fake-pregnancy in the grief-laden “Appropriate Love” (1991) absolutely bone-chilling. First collected in Egan’s excellent debut collection Axiomatic (1995), “Appropriate Love” is a science fiction horror story as original and “high concept” as Chiang’s “Story of Your Life,” which served as the basis of Denis Villeneuve’s 2016 film Arrival (adapted by screenwriter Eric Heisserer).

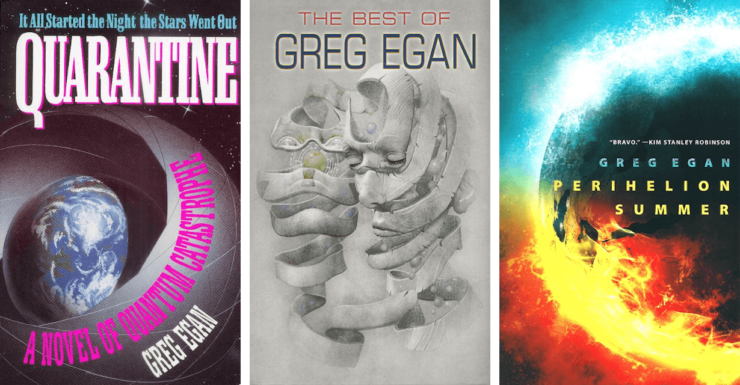

For more oomph and action, there are plenty of places to start: Pick any story from The Best of Greg Egan (Subterranean Press, 2019; North American edition publishing July 2020 with Night Shade Books). Devour “Chaff” (1993) or “Silver Fire” (1995). Sample “The Planck Dive” (1998) or “Crystal Nights” (2008) on the author’s website for free. Or read “Uncanny Valley” (2017), “The Nearest” (2018) or “Zeitgeber” (2019) here on Tor.com. (I’ll return to some of these stories below.)

Buy the Book

Perihelion Summer

The BBC radio adaptation of Ted Chiang’s “Understand” (1991)—read by Rashan Stone—is one of the finest productions of all time for me; it’s basically director Neil Burger’s Limitless (2011) in prose. If the BBC can adapt and produce a new version of “Understand” for a wider audience, I don’t see why “Luminous” can’t benefit from similar treatment. Both Chiang and Egan are best known for their short works of science fiction built around complex ideas and hard science, and both “Understand” and “Luminous” explore the uncharted frontiers of mind, knowledge, and consciousness. While Chiang is less prolific than most SF writers, including Egan, Chiang is certainly more influential than most SF writers—the very definition of a genre “superstar.”

That brings us back to the old question: Why isn’t Greg Egan a superstar, yet? Well, Jon Evans’s answers are still relevant: Egan is demanding, to say the least. There are writers whose work benefits from being read with “a pad of paper and a pen beside it,” of course. But many casual readers don’t imagine diving into fiction as a pastime that requires the kind of “note-taking and diagram-scribbling” Egan describes—unless the reader is a writer or an academic, perhaps.

Egan’s fiction is more scientifiction than most of what passes as science fiction today. He believes that science fiction should be as hard, rigorous, and scientific as physics or mathematics. And while he is too “shy” to upload his mugshot on the Internet—there isn’t a single author photograph online or on the jacket of his books—he is certainly not shy about making a scientific contribution or two when he can. According to Quanta Magazine: “A new proof from the Australian science fiction writer Greg Egan and a 2011 proof anonymously posted online are now being hailed as significant advances on a puzzle mathematicians have been studying for at least 25 years.”

There are writers and there are writers’ writers, and I read Egan because I am a writer. For most readers, Egan’s books offer epic or intellectual “conquests”—he is the go-to man for challenging, complex ideas, whose fictional inventions are discussed on Silicon Valley forums. His fiction is dissected and taught in maths classes.

He is one of the authors featured in the University of Illinois Press’s Modern Masters of Science Fiction list edited by Gary K. Wolfe. Karen Burnham’s terrific book-long study Greg Egan, published in 2014, remains an essential reader’s companion to his work that illuminates the reclusive author’s themes, motives, and characters. I do hope Burnham receives the time and incentive to bring her monograph up to date when the next edition of the book comes out. Nevertheless, it’s a good place to start, compared to searching through online reviews or Reddit threads, to make sense of a challenging and mind-expanding body of work.

In case you haven’t fully encountered the phenomenon called Greg Egan or would like to take a trip down memory lane, as they say, the author recommends these five short stories for your reading pleasure:

“Learning to Be Me”

I was six years old when my parents told me that there was a small, dark jewel inside my skull, learning to be me. Microscopic spiders had woven a fine golden web through my brain, so that the jewel’s teacher could listen to the whisper of my thoughts. (p. 7, The Best of Greg Egan)

If we can trust an artificial heart, surely we can trust the jewel—a powerful computer—to replace our brain, right? Well, there are concepts like ego and identity attached to the organic supercomputer that is our brain… Science fiction puts the reader in an uncomfortable situation, forcing us to experience the characters’ internal and external struggles, and by the end of these journeys, we become them or unlike them.

The brain scans of neural activities show little difference between reading about and living the same experience. If the jewel comes with the promise of youth and longevity, as it does in “Learning To Be Me,” I’ll sign up for the upgrade (minus the existential crises) any day.

“Reasons to Be Cheerful”

I sat on the floor, trying to decide what to feel: the wave of pain crashing over me, or something better, by choice. I knew I could summon up the controls of the prosthesis and make myself happy—happy because I was “free” again, happy because I was better off without her… happy because Julia was better off without me. Or even just happy because happiness meant nothing, and all I had to do to attain it was flood my brain with Leu-enkephalin. (p. 254, The Best of Greg Egan)

In Stephen King’s mammoth post-apocalyptic novel The Stand, Frannie Goldsmith (Fran) refuses to marry Jesse Rider because she thinks he wouldn’t understand or appreciate her involuntary giggles or laughing condition. Egan’s protagonist in “Reasons to Be Cheerful” has a real medical condition that releases “happy” chemicals in his brain. As a result, he is “cheerful” all the time. After a surgical intervention, he can deliberately choose his exact response to what makes him happy. When you can choose what makes you happy, is such happiness even “real”?

Side note: I don’t think Fran would have said yes to such a medical intervention. She didn’t want to marry Jesse, and you know the rest of the story. Had she kept a diary during this time, and had Jesse stolen a peek, I don’t know if he would have become Jackal or something, if not the alpha version of Harold Lauder, aka Hawk.

In other words, Egan’s characters can be as real as King’s. Seriously.

“Uncanny Valley”

[Adam] searched the web for the phrase [“targeted occlusions”] in the context of side-loading. The pithiest translation he found was: “The selective non-transferral of a prescribed class of memories or traits.”

Which meant that the old man had held something back, deliberately. Adam was an imperfect copy of him, not just because the technology was imperfect, but because he’d wanted it that way.(p. 586, The Best of Greg Egan)

When your original decides to hold something back from you, what do you do? You become a sleuth, discover a body or two. You can read Egan’s version of a murder mystery here on this site.

Egan is vocal about the rights of “sentient” software or AI—which brings us to the next story.

“Crystal Nights”

Daniel said, “You’re grateful to exist, aren’t you? Notwithstanding the tribulations of your ancestors.”

“I’m grateful to exist,” [Julie] agreed, “but in the human case the suffering wasn’t deliberately inflicted by anyone, and nor was there any alternative way we could have come into existence. If there really had been a just creator, I don’t doubt that he would have followed Genesis literally; he sure as hell would not have used evolution.” (p. 483, The Best of Greg Egan)

In “Crystal Nights,” the fastest way to create a human-like or advance artificial intelligence is through Evolution—the birth and death of multiple generations of sentient algorithms and their collective suffering, i.e. the human condition. Daniel’s role in the story reminds me of the pitfalls of playing god or exposing yourself as the master creator—remember the alien encounter in Prometheus which ends in a beheading?

“Crystal Nights” is a fine story, one eminently worthy of Hollywood or Netflix adaptation, for it crystalizes (ahem) Egan’s ethical concerns relating to AI development for all to see. If you’re a fan of Black Mirror, you should binge-read The Best of Greg Egan immediately, and be sure not to skip this one.

“Zero for Conduct”

Latifa found her way back to that desk. The keys were hanging exactly where she remembered them, on labeled pegs. She took the one for the chemistry lab and headed for the teachers’ entrance.

As she turned the key in the lock her stomach convulsed. To be expelled would be disastrous enough, but if the school pressed criminal charges she could be imprisoned and deported. (p. 516, The Best of Greg Egan)

Latifa is a young Afghani immigrant girl in Iran. She is a child prodigy who achieves a rare feat, overcoming the perceived challenges and shortcomings resulting from her origins and circumstances. “Zero for Conduct” is a story about the scientific spirit, the quest for understanding and invention, and the personality and genius required to own and profit from such endeavors. I imagine that this story could become a film along similar lines to Chiwetel Ejiofor’s The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind (2019, written by William Kamkwamba) or perhaps a storyline set in the larger world of a TV series based on Egan’s novel Zendegi (2010), also set in Iran.

***

Reading strategies and preferences as the international community shelters under quarantine from the global pandemic COVID-19 will, of course, vary. Stephen King’s The Stand: The Complete and Uncut Edition (1990), clocking in at 500,000 words, might be a good choice for those looking for the end-of-the-world fiction with adolescent optimism or occult mysticism. It’s pure escapism and entertainment unburdened with modern-day concerns such as scientific accuracies and diversity of faiths and characters.

Those interested in award-winning contemporary trilogies might consider series like N.K. Jemisin’s the Broken Earth, Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem, Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch, or Jeff VanderMeer Southern Reach trilogies. And then there are hard science fiction trilogies such as Egan’s Subjective Cosmology, featuring Quarantine (1992), Permutation City (1994) or Distress (1995), and the Orthogonal series, which comprises The Clockwork Rocket (2011), The Eternal Flame (2012) and The Arrows of Time (2013).

Egan’s short stories and novels may not be seen as obvious candidates for film or TV adaptations by screenwriters, directors, and producers who imagine the practical difficulties inherent in translating his alien creatures, dimensions, concepts, and worlds into a new medium. Or they might suspect Egan’s fiction will simply be too complex to work as a mainstream film or a web series. Even Cixin Liu’s comparatively screen-friendly The Three-Body Problem, which was in the works in 2015 and rumored to release in 2017, has now been postponed indefinitely. Making successful cinema or TV is certainly expensive and tricky—even The Expanse has had to fight to survive despite all the critical acclaim it’s received.

And yet, while Egan has only one short film to his credit to date, I’m confident that there will be a legion of adaptations of his work made by amateurs and professionals in the days and years to come. As film technologies, audiences, and markets continue to “mature,” filmmakers will find new and creative ways to adapt and resurrect all types of speculative fiction, whether hard, soft, or mundane. If the flesher humans fail to recognize his genius, there’s always a filmbot to rescue him from relative obscurity to Matrix-like Hall of Fame. But until we reach that point, it’s up to us as readers to explore and champion Egan’s work—there are so many excellent places start (including the five above), and so many stories to revisit, paper and pen in hand. What are your favorites?

Salik Shah is the founding editor of Mithila Review, a journal of international science fiction and fantasy. His poetry, fiction, and non-fiction has appeared in Asimov’s Science Fiction, Strange Horizons, Samovar, and Juggernaut, among other publications. You can find him on Twitter @salik. Website: http://salikshah.com.

I see the point, in a way, but to me, Greg Egan has obviously been a superstar since the flood of great short work began in the early 1990s. Seriously, for SF insiders, there’s been no doubt since then.

I consider his novelette “Wang’s Carpets” (often ignored, as it became part of the novel Diaspora — it’s better in its novelette form) to be one of the greatest SF stories of the past few decades.

I first encountered Egan in the late, lamented Pulphouse The Hardback Magazine, with his story “The Moral Virologist” — genius stuff. I really enjoyed the first couple of novels of his I picked up, especially Permutation City, but increasingly found his work to be very dry, and the characters seemed less important than the science MacGuffins. Perhaps not as much as, say Arthur C. Clarke, but enough that I stopped buying his fiction. I’d probably pick up the occasional book and enjoy it, but he’s not at the top of my list anymore.

Endorsing both ecbatan & joelkinkle’s comments: Egan came into the field as a more or less instant supernova; “Wang’s Carpets” is a work of genius, and only one of many from this period; but the escalating rigour of his work over the last decade-plus has knocked him off the list of writers I follow.

I would also note a recurrent issue in the early to mid-period work: when he takes a lighter tone, there’s a cynicism & bitterness to the humour I find difficult to enjoy. I can’t think of many writers whose best work sits alongside quite so many stories I’d warn people not to read first.

Egan’s Dichronauts is the acme of his difficult but rigorous longer fiction. Well worth the work, but yes, you’d better have that pad and pencil by you as you read. I had to go to his website and look at his background material before I really understood what was going on there.

To me the question is why he is not the Science Fiction’s Superstar.

In opinion, he is a Superstar already.

About Zendegi – a SF book about fatherhood and parenting. The protagonist Martin has married an Iranian woman, albeit not one he has found in front of a divorce court. They are rising a son, who is just about to start going to school. On his first day of school a disaster strikes. And then another one. Until we understand that ultimately this is not a trans-humanist post-singularity novel, but a story of personal loss – loss of family and friends, loss of a country and culture. This is a novel about how to cope with those blows of the fate. Deep underneath the engaging story Egan tries to answer the question if technology can be of any help to us in this impossible endeavor. In my interpretation of the novel, the author ultimately paints the technology as a tool – not a goal in itself as other hard science fiction writers often do. He points that the real help and friendship come from the people. Our failures and successes come from and are measured against the human relationships, not against technological achievements. The novel’s conclusion is neither particularly optimistic, not too pessimistic, but it is surely one that made my hearth heavy with sadness. I think Zendegi was badly overlooked and undervalued by the general readers. As far as I can find on the Internet, it earned no awards or nominations. It is a rare novel in the genre about the parenting, loss and change. The characterization is good – perhaps some other reviewers have mistaken what I think are reserved attitudes of some protagonists for shallow descriptions. I highly recommend Zendegi. It is a complex book, but not mathematically, as Diaspora was; it is an intricate piece of fiction on political, psychological and cultural level. At the end, one of the main characters reaches a satisfying closure, but the story line of the other leaves some unanswered questions, possibly hinting at a sequel.The inner monologues of Martin, when he speaks to himself as if he is parenting his son, are especially powerful. I especially appreciated being given glimpses into the artificial reality environment Zendegi (the word means life in Persian), into the Persian mythology. Many Persian words are sprinkled on the novel without translation (but there is always Google) and help to create a special atmosphere.

Egan’s latest short story collection is pretty tasty.

SPOILER!

Last warning!

It’s only after a few – mind blowing – stories that you realise that some of them are connected. It’s like you’re reading a novel by stealth.

Highly recommended.