The future is arriving sooner than most of us expected, and speculative fiction needs to do far more to help us prepare. The warning signs of catastrophic climate change are getting harder to ignore, and how we deal with this crisis will shape the future of humanity. It’s time for SF authors, and fiction authors generally, to factor climate change into our visions of life in 2019, and the years beyond.

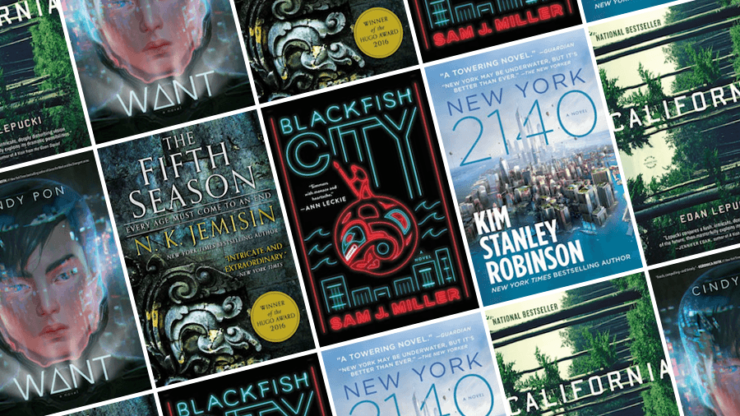

The good news? A growing number of SF authors are talking about climate change overtly, imagining futures full of flooded cities, droughts, melting icecaps, and other disasters. Amazon.com lists 382 SF books with the keyword “climate” from 2018, versus 147 in 2013 and just 22 in 2008. Some great recent books dealing with the effects of environmental disasters include Sam J. Miller’s Blackfish City, Edan Lepucki’s California, Cindy Pon’s Want, Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140, and N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy. It’s simply not true, as Amitav Ghosh has suggested, that contemporary fiction hasn’t dealt with climate issues to any meaningful degree.

But we need to do more, because speculative fiction is uniquely suited to help us imagine what’s coming, and to motivate us to mitigate the effects before it’s too late.

Climate change “no longer seems like science fiction,” Robinson recently wrote. And in many ways, this seemingly futuristic nightmare is already upon us. The rate of melting in Antarctica’s ice sheet has gone up by 280 percent in the past 40 years, and the oceans are warming faster than predicted. Already, there are wildfires and abnormally destructive storms in the United States—but also, widespread famine in East Africa and the Sahel region, as rains become erratic and crucial bodies of water like Lake Chad shrink. Millions of lives are already threatened, and even the current federal government predicts it’s going to get scarier.

“I live in New York City, and I’m scared shitless about how climate change is already impacting us here, and how much worse it will get,” says Blackfish City author Miller. “We still haven’t recovered from the damage Hurricane Sandy did to our subway tunnels in 2012. And I’m infuriated at the failure of governments and corporations to take the threat seriously.”

Jemisin says that she didn’t set out to create a metaphor for climate change in the Broken Earth trilogy, but she understands why so many people have viewed it as one. “I get that it works as a metaphor for same, especially given the revelations of the third book, but that just wasn’t the goal,” she says. Even so, Jemisin says that she believes “anyone who’s writing about the present or future of *this* world needs to include climate change, simply because otherwise it’s not going to be plausible, and even fantasy needs plausibility.”

It’s become a cliché to say that science fiction doesn’t predict the future, but instead just describes the present. At the same time, because SF deals in thought experiments and scientific speculation, the genre can do more than any other to help us understand the scope of a problem that’s been caused by human technology, with far-ranging and complicated effects.

Science fiction “provides a remarkable set of tools” for exploring intricate systems such as the atmosphere, ecosystems, and human-created systems, says James Holland Jones, an associate professor for Earth System Science and Senior Fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment at Stanford University. “These are all complex, coupled systems. Tweak something in one of those systems and there will be cascading, often surprising, consequences.” A science fiction novel provides a perfect space to explore these possible consequences, and what it might be like to live through them, Jones says.

“I think that this modeling framework is just as powerful as the mathematical models that we tend to associate with the field” of environmental science, Jones adds. “SF allows the author—and the reader—to play with counterfactuals and this allows us to make inferences and draw conclusions that we otherwise couldn’t.”

We need to imagine the future in order to survive it

And any real-life solution to climate change is going to depend on imagination as much as technical ingenuity, which is one reason why imaginative storytelling is so vitally important. Imagination gives rise to ingenuity and experimentation, which we’re going to need if humans are going to survive the highly localized effects of a global problem. Plus imagination makes us more flexible and adaptable, allowing us to cope with massive changes more quickly.

Jones cites a 2016 interview with Mohsin Hamid in The New Yorker in which Hamid says that our political crisis is caused, in part, by “violently nostalgic visions” that keep us from imagining a better future.

Says Jones, “I think it’s hard to overstate how important this is. We are actively engaged in a struggle with violently nostalgic visions that, like most nostalgia, turn out to be dangerous bullshit.” Science fiction, says Jones, can show “how people work, how they fight back, how they engage in [the] prosaic heroism of adapting to a changed world. This is powerful. It gives us hope for a better future.”

And that’s the most important thing—solving the problem of climate change is going to require greater political willpower in order to overcome all the bullshit nostalgia and all of the entrenched interests that profit from fossil fuels. And empathizing with people who are trying to cope with the effects of climate change is an important step toward having the will to act in real life.

“To me, it’s the job of a science fiction writer—as it’s the job of all sentient beings—to not only stand unflinchingly in the truth of who we are and what we’re doing and what the consequences of our actions will be, but also to imagine all the ways we can be better,” Miller says.

And it’s true that there’s no version of Earth’s future that doesn’t include climate change as a factor. Even if we switch to entirely clean energy in the next few decades, the warming trend is expected to peak between 2200 and 2300—but if we insist on burning every bit of fossil fuel on the planet, the trend could last much longer (and get much hotter.) That’s not even factoring in the geopolitical chaos that’s likely to result, as whole populations are displaced and/or become food-insecure.

So any vision of a future (or present) world where climate change is not an issue is doomed to feel not just escapist, but Pollyannaish. Even if you decide that in your future, we’ve somehow avoided or reversed the worst effects of climate change, this can’t just be a hand-wavy thing—we need to understand how this solution happened.

Heroes, and reason for hope

Science fiction, according to Jones, provides an important forum for “humanizing science and even politics/policy.” Pop culture and the popular imagination tend to depict scientists as evil or horribly misguided, and civil servants as “contemptible, petty, power-hungry bureaucrats.” But SF can show science in a more positive light, and even show how government is capable of implementing policies that “will get us out of the mess we’re currently in,” says Jones.

“With Blackfish City, I wanted to paint a realistically terrifying picture about how the world will change in the next hundred years, according to scientists,” says Miller—a picture which includes the evacuation of coastal cities, wars over resources, famines, plague, and infrastructure collapse. “But I also wanted to have hope, and imagine the magnificent stuff we’ll continue to create. The technology we’ll develop. The solutions we’ll find. The music we’ll make.”

“The Road/Walking Dead-style abject hopelessness is not entertaining or stimulating to me,” adds Miller. “Humans are the fucking worst, yes, but they’re also the fucking best.”

Buy the Book

The City in the Middle of the Night

Robinson has been called the “master of disaster” because of how often he depicts a world ravaged by climate change, in books ranging from the Science in the Capitol trilogy to the more recent New York 2140. But Jones says Robinson’s novels “are generally incredibly hopeful. People adapt. They fight back. They go on being human. They work to build just societies. And the heroes are just regular people: scientists, public servants, working people.”

Jones also gains a lot of hope from reading Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, with its “visceral exploration of human adaptation.” He also cites the novels of Margaret Atwood and Paolo Bacigalupi, along with Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, Richard Powers’ The Overstory, and Hamid’s Exit West. (I’ve also done my best to address climate change, in novels like All the Birds in the Sky and the forthcoming The City in the Middle of the Night, plus some of my short fiction.)

Speculative fiction has done a pretty good job of preparing us for things like social media influencers (see James Tiptree Jr.’s “The Girl Who Was Plugged In”) or biotech enhancements. But when it comes to the greatest challenge of our era, SF needs to do much more. We’re not going to get through this without powerful stories that inspire us to bring all of our inventiveness, far-sightedness, and empathy to this moment, when the choices we make will shape the world for generations.

So if you’re writing a near-future story, or even a story set in the present, you have an amazing opportunity to help transform the future. Even if you don’t want to write a story that’s explicitly about climate change, simply including it in your worldbuilding and making it a part of the backdrop for your story is an important step towards helping us see where we’re headed, and what we can do about it. In fact, in some ways, a fun, entertaining story that just happens to take place in a post-climate change world can do just as much good as a heavier, more serious piece that dwells on this crisis. And really, we need as many different kinds of approaches to climate issues as possible, from hard-science wonkery to flights of fancy.

Few authors, in any genre, have ever had the power and relevance that SF authors can have in 2019—if we choose to claim this moment.

Charlie Jane Anders’ latest novel is The City in the Middle of the Night. She’s also the author of All the Birds in the Sky, which won the Nebula, Crawford and Locus awards, and Choir Boy, which won a Lambda Literary Award. Plus a novella called Rock Manning Goes For Broke and a short story collection called Six Months, Three Days, Five Others. Her short fiction has appeared in Tor.com, Boston Review, Tin House, Conjunctions, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Wired magazine, Slate, Asimov’s Science Fiction, Lightspeed, ZYZZYVA, Catamaran Literary Review, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency and tons of anthologies. Her story “Six Months, Three Days” won a Hugo Award, and her story “Don’t Press Charges And I Won’t Sue” won a Theodore Sturgeon Award. Charlie Jane also organizes the monthly Writers With Drinks reading series, and co-hosts the podcast Our Opinions Are Correct with Annalee Newitz.

If that is the good news, then I hate to hear what the fucking bad news is. You have it the wrong way around. By putting that in your books you are telling people it cannae be solved, that there is nae point trying, and that it disnae matter what they do. You’re reassuring the do nothing brigade, and ra hope is ae a lie troupe that they can just keep oan preaching about the futility o life and hoo selfishness is ra richt coures o action.

Aye, you dae, an this how:

SF Authors need to be writing about post-scarcity, the benefits of post scarcity utopias, and the path to them too. Not reassuring each other than dystopia is the only option, not saying that the path to post scarcity is bad, not buying into the idea that hatred will always be with us and there is a serpent in every Eden. Half the problems in the world can be laid at the feet of those who have said it is too hard, or that trying to change for the better is unrealistic in some way, and SF authors have joined in with that lemming like too. Dare to believe things could be better, dare to accept that we can have all our needs met and it can be good, dare to condemn those who claim otherwise. Then you’ll have achieved some damn good speculative fiction, and helped change the world a little better than constant strife fiction ever could.

As for climate change and environmental fiction, SF authors could dae a lot worse than look tae things like yon Captain Planet and Ferngully as models; with the stipulation that the only real problem wi those was that apparently they were too damn fucking subtle in their messaging.

I beleive that SF-writers should write from their heart, and not from some kind of political agenda.

Personally, I’d like more SF about climate SCIENCE, not climate change thrown in as mere background material. Something like Bruce Sterling’s Heavy Weather but updated and more science-y, maybe even to Neal Stephenson infodump levels. If Heinlein inspired lots of people to work in aerospace, lets see some people inspired to work on climate science!

I think by including it as part of the background, climate change will just end up being one of those amusing things that SF writers “got wrong” like all those stories based on an impending ice age written in the 1970s and 80s.

The problem is that much – if not most – SF concerns existential threats to humanity vastly more serious than even the worst prognostications related to CO2-induced global warming. A realistic depiction already puts us in near-future territory that many would dismiss as the realm of the ‘techno-thriller’ rather than true SF.

This is why I started Little Blue Marble, a pro-paying flash fiction market solely for climate change speculative fiction: to encourage more writing about climate change.

@vinsentient, #3: If you are interested in fiction *about* climate science, you might like Kim Stanley Robinson’s Science in the Capitol trilogy. I read it in its original three-book form — Forty Signs of Rain, Fifty Degrees Below, and Sixty Days and Counting. But KSR has cut it and released it as a (still long) one-volume novel, called Green Earth. I can’t vouch for the short version, but it was cut by the author, so presumably it’s the one to get.

I guess that Solarpunk fiction would be considerated as SF that deals with Climate Change at the same time that offer possible solutions, isn’t?

I am a big fan of Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985) – not a novel, a polemic about news being treated as entertainment. Makes me want to go back to a scarcity-mode Internet of dial-up, when one was selective about sites consulted because it t o o k s o l o n g to get content. No stupid Facebook viral posts.

#Solarpunk is here to save the day. I’m personally a Solarpunk author and I hope Tor will be willing to work with agents promoting solarpunk long-form novels such as mine, The Carbon Coast!

The sifi channel dumbed everyone down. For years promoting the earth is the enemy and only bad science/magic will stop it. Promoting dystopian cultures. Sharknado is the perfect example. This with the “no child left behind” & the “faith based initiative” helped seal this ignorance.

I admit to being somewhat amused by the whole “climate change” debate. Mind you, my degree was in Geology and Geophysics. . . which shows that Planet Earth is currently in an Ice Age, has been for the past ~4.5 million years, and that we’re merely between Continental Glacial Advances.

But let’s assume that the concerns for Climate Change are real. All it would do is return the planet to the climate it has experienced for most of the past billion or so years. . . .

People have been writing about doomsday due to humans destroying themselves for a long time, now. In the eighties, we were all supposed be fighting each other over soylent green in a desert wasteland being chased by sentient robots… or something… by the 2000.

Then there’s waterworld.

We’ve gone over the population “limits” and yet, crime rate has dropped, more countries enjoy 1st world status (in spite of the US bombings), and we are no longer running out of oil. Most starving populations are due to government mismanagement than it is due to food shortages.

There’s a lot of people who won’t listen now because a lot of them heard it all before and if you try to shoehorn this into your stories, it will be met with a lot of eye-rolls and low reviews.

I think the only thing that would be beneficial is to write what we should strive to be. People mostly read to be entertained, not to be preached at.

SF authors have been writting about climate change and scarcity for decades.

While many of these books posit different causes and effects, the topic is not new.

Hall Clements’ “Nitrogen Fix”, posists that man alters the planet that most free oxygen is removed from the atmosphere.

Niven & Pournells’ “Fallen Angel” posists a frozen earth after a “fix” to global warming goes wrong and plunges the earth into a deep ice age.

There’s a great sci-fi book with climate change as a theme called Last Centurion. Very good. Highly recommend.

As always, we ask that you keep the tone of this discussion civil and constructive; you can find our full Moderation Policy here.

There’s a scientifically modelled SF book on climate change, Mother of Storms, by John Barnes, put out in 1994. Grim, with a hopeful ending. Pretty decent plotting and characters too.

I’d say it’s more important for writers in general to be talking about climate change, not just sci-fi writers. It’s pretty much preaching to the choir with most science fiction fans anyway. Less so with other genres. How about a True Detective-style procedural where climate change figures into the plot? Or a reality TV series? Or a game show? Or a climate change musical?! Well, you get the idea.

You wanna broadcast a message, you gotta go broad.

IMO an “Alarmist” novel would just hurt the author’s career – and the pond is way too tiny with the monopolized markets vs the flood of digital indie publishing…

A while back there was this awesome novel – “Random Acts of Senseless Violence” by Jack Womack. Pretty much predicted what’s happening now, and I thought more works should be like that – from the boom of the 90s realizing there was too much upflow of money and outflow of jobs…

Well the novel – the critics spewed venom on it and it didn’t sell well. The big thing they used to dismiss it was the plot element that films weren’t made anymore they just re-released old stuff to capitalize on nostalgia… After all, during the real “Great Depression” the film industry was at its height, right?

But, whoops, look how reality can out-do what any author would dare use in fiction… They don’t just re-relase films, they re-boot them… Spend 10x as much money as the originals. And they SUCK. And they keep on making more. G-D help them if they risk $ on NEW writers, new stories…

Hey, even earlier go to “The Sheep Look up” and to a lesser extent “Stand on Zanzibar” – 70s era predictions on social trends, enviornmental destruction, antibiotic resistant diseases… A huge catalog of predictions that came true. Again ultra hated book, I think the Sheep one nearly derailed John Brunner’s career.

Oh, and way way way back, H.G. Wells’s book “When the Sleeper Wakes” actually predicted Netflix for the most part. Also the vast divisions in class more as we see today (born lucky, good business) versus then (right family, nobility, peasant). And it’s the book most hated, most often excluded in collections….

So, TOR, you want someone to make a novel that gets people to clamor for emergency enviornmentalism – how about propping up a NEW scifi/fantasy writer who can write a good story and supporting their work for a few books as long as they keep writing good and try to get movies and such made so they launch a career not derail it with Limbaugh fans threatening their death….?

Oooooh, yes. Love “Fallen Angels” and “Last Centurion”.

Don’t forget Paolo Bacigalupi

Indeed, a very important topic and true, it has been a major topic in SF for some time.

One recent book that hasn’t been mentioned, but deserves it, is Austral, by Paul McAuley.

Set in an era when the warming has made Antarctica habitable, it tells the story of the birth of a new nation in the new continent. at the time when the original enthusiasts have been replaced by “efficient managers”. Very humanistic novel, great characters. Parallels with a lot of classics – from Jack London’s stories to Ursula Le Guin’s Left Hand.

Ben@19: Oscar Wilde wrote: “One must have a heart of stone to read the death of little Nell [a Dickens character] without laughing.”

Brunner’s _The Sheep Look Up_ suffers greatly from the Little Nell factor. It is the literary equivalent of Lou Reed’s Berlin.

No they don’t NEED to do anything of the sort. God, I hate that finger wagging “we need to talk about…”language.

Firstly, science fiction writers HAVE been addressing environmental disasters for decades. John Christopher’s “The Death of Grass” from 1956 is a good example.

Secondly, anyone who says this does not understand what fiction is, or how it works. It’s not fiction’s job to forecast what might or will happen, let alone make recommendations, and if it manages to do so, that’s a happy coincidence. To quote Martin Amis: “Fiction is about what didn’t happen and science fiction is about what isn’t going to happen.” Fiction writers tell stories: myths, if you like, dramas that portray unlikely, tragic or wonderful things that happen to people and which, in doing so, illustrate things about what it is to be alive and human (or alien, or a robot) in a way that can never be captured by non-fiction, that deals with data and populations.

In doing this, fiction can leap ahead of current or even near-future events and forecast or rather prophesy what it might mean to feel alive in 100 or 1000 or a million years’ time, sometimes with uncanny intuition. But that’s still not its job. Fiction, in its ability to shortcut to the fantastic, the weird, the idiosyncratic, does not talk about today: it invites people to *feel more keenly* what it’s like to be alive today, or yesterday if you’re writing historical fiction, or tomorrow if you’re talking about science fiction, or elsewhere if you are writing about people not like you. It doesn’t, if it’s any good, portray a future society but instead puts you inside the skin of someone living in that society (or lack of it).

And fiction writers are not scientists; they are poets, artists who manipulate symbols Ito something more resonant.

Take an example. Philip K Dick was no scientists but had a keen fascination with fundamental philosophical questions such as: “How do I know I’m alive? How do I know if my memories are real? How do I know if my existence is a simulation?” He wrote crazy, chaotic novels about characters so afflicted by these existential crises that their experience fractures the very narrative in which they participate.

In churning out his stories, he did manage to dramatise scientific questions being asked at the time by neuroscientists, psychologists and cyberneticians and also drew up future scenarios that were uncomfortably close to dilemmas we grapple with today. Politically, some would say that his fascination with false experiences and identities spoke eloquently of the way US capitalism was commodifying people’s very lives, and was forecasting the echo-chamber of social media.

But the point is that he didn’t write to forecast or warn. That’s the job of scientists and economic modellers. He was confronting people with the weirdness of it all; that’s what artists do. He was inspecting reality, and finding it terrifying, wonderful and tragic. The same could apply to the fragmenting dystopias of JG Ballard, to the reality-as-computer-game cyberpunk of William Gibson, to the ennui-plagued post-scarcity society of Iain Banks, to Ursula le Guin’s lonely proto-feminist heroines lost amid the stars.

Science fiction writers are artists, and artists should never do what they SHOULD do.

Thank you, Charlie Jane.

As the effects of anthropogenic enhanced and accelerated climate change become more and more prevalent, ignoring it and not addressing it is at odds not with some medium or long term future, but rather the present that SF written speaks to now.

FWIW,I used to like Fallen Angels, until I re-read it, older, and more experienced, and realized I did not like the politics the authors present regarding environmentalists after all: the environmentalists are anti technology AND anti-science, obfuscating science for their own political ends. It s written very cleverly to get the reader to see them as evil, see their agenda as evil, and I feel shame I didn’t see it the first time through.

@12 Nancie

I think you are missing the fact that not all of those possible catastrophes were avoided by waiting them out. Because they were publicized (well, and because of economic signals) a lot of very hard work was put in by armies of scientists and engineers to avert them.

Climate change is tackled thoughtfully in Brian Andrews’ thriller, RESET, which was the #1 SF title on Amazon this week. Definitely worth a read (or listen – the audiobook is narrated by the incomparable Ray Porter).

A very good and timely post by Charlie Jane. Bravo. And yes, Amitav Ghosh was wrong to look down at genre fiction as beneath him. His new novel Gun Island is a cli-fi genre novel set for release in June. And since cli-fi is a subgenre of Sci-fi, his new novel fits in well with Anders’ op-ed here. This 21st Century is going to be an interesting one, and SF will lead the way.

IMHO, writers of any gender should indeed have opinions and cast their votes about the pressing issues of their time, but they should write about whatever is in their hearts.

This. But also more SF about positive alternative futures, where we don’t just give up.

Apocalyptic fiction is just lazy and unimaginative.

No author NEEDS to write about anything other than what they enjoy writing about and maybe what they think readers will enjoy reading.

Carrie Vaughn’s Bannerless and Wild Dead describe the effects of climate change.

What modern SF authors need to be doing right now that they have been doing too little of lately is telling good stories. The last thing we need is a series of lectures plugged into a supposed dramatic narrative. Now if they choose to incorporate climate change speculation into their settings and plot, that’s fine as long as it doesn’t distract from the characters and the story. Didactic SF is as boring as hell.

@37: THIS. A hundred times this.

Couldn’t agree more. Hate to say it, but I think a hero of some epic proportion is what it will take to create the necessary momentum for any work of fiction to move the masses to action. Must become a “blockbuster” film, too. Great article.

Well I was recently looking at some of the data about the shifting of the magnetic poles and some of the effects that happen because of it. It is mentioned that the shifting poles effects weather, and also damages the ozone layer due to the weakening of the magnetic fields. So the ‘hole in the ozone’ that was at the south pole could be just as much that as any form of pollution. Is it true? I don’t know…but every time I hear ‘the debate is over’, I tend to doubt the group saying it….since debate on things we don’t know for certain shouldn’t be over till we all agree it is certain, not because someone says so. And on ‘Global Warming’ now ‘Climate Change’ because the world stopped warming….so apparently the debate and science aren’t over or done.

My biggest problem with the latest political scare being forced into my fiction reading is that I get too much of politics and political science (since science is not really needed if the idea fits the political desires) on tv and in just about ever other area.

Sadly I totally have to disagree with writers trying to shove this into stories. Stories are to escape the political nightmare and enjoy good fiction that supports a plot driving that story. I’ve stopped reading quite a few books that get to preachy. If I want a sermon I’ll go to church. When I want good scifi, I expect to escape into a world that doesn’t try and tell me how I should live or how I’m wrong for not being one way or another.

Thanks for the article; I have shared it and agree. Science fiction is now a love story (to quote a friend), and climate change is a subject in fiction that propels us right now–a subject many more are tackling and being successful at than some believe! See https://eco-fiction.com/title-author-publication-date-search/ for a database of over 600 novels, the majority of them dealing with the modern environmental place we’re finding ourselves in.

One of my favourite climate change books is Robert Silverberg’s “Hot Sky at Midnight” – he makes a profound connection between ecology, biology and culture. The cultural (captialist) activities that lead to irreversible climate change find a potential solution not in preserving an already changed ecology but instead changing our biology to suit the new environment – quite a challenging idea but possibly more feasible than reversing climate change!

If you haven’t read it, check it out; it’s a book that stays with you long after you have put it down.

Thanks for this Charlie Jane! i’d love to see companion work from Tor and other publishers, about efforts they are making now and expected targets for 2020, in changing climate impacts. How can book presses of different sizes, and print and digital literature and journalism publishing projects, show leadership in making their operations not just carbon neutral, but successful in distributing texts and also net balance ecologically regenerative impacts? There’s companion leadership opportunity too among sci fi (and other genre) authors, and among fans/consumers, in demonstrating commitment to not just needed narratives (yes, not merely dystopic ones), but also in choosing to produce or promote and purchase texts that circulate with paper, ink, and electricity sourced sustainably and publicly accounted for. Cultural producers can level up re: ecological budgets for our activities, and not wait for legislative requirements. Teamwork for a creatively manifested future!

Just a reminder about the site’s Moderation Guidelines. This discussion is an opportunity to engage with the ideas and opinions discussed in the original post in a civil and constructive manner–as always, rude, aggressive, or dismissive comments aren’t part of the conversation.

@48: You may be interested in this overview of Macmillan’s sustainability efforts over the last decade.

John Barnes nailed it in 1994 with Mother of Storms. Everything he wrote about is coming to pass. I’ve never forgotten it.

https://www.amazon.com/Mother-Storms-John-Barnes/dp/0312855605.

This is my first-ever on-line comment.

It seems that most readers are unaware of Philip Wylie’s apocalyptic novel, The End of the Dream, written in 1972. I did not read the entire comments list and maybe it is mentioned there.

In The End of the Dream, humankind’s despoilation of the earth, leads to the end of life. I read it when I was in my 20s and it has haunted me ever since.

Everyone knows Silent Spring ; I wish more people knew The End of the Dream.

I take this opportunity to also mention Wylie’s The Disappearance, in which:

“An unexplained cosmic “blink” splits humanity along gender lines into two divergent timelines: from the men’s perspective, all the women disappear and from the women’s, all men vanish. The novel explores issues of gender role and sexual identity. It depicts an empowered condition for liberated women and a dystopia of an all-male world. Wylie’s setting allows him to investigate the role of homosexuality in situations where no gender alternative exists.”

Wylie was a very prescient writer. His work couldn’t be more relevant today.

Another Cli-Fi novel not mentioned, but one I found fascinating, is Claire Vaye Watkins novel, Gold, Citrus, Fame. It is set in a world where water shortage has become catastrophic.

When I began reading SF, there were still stories in reprint anthologies about the coming population implosion. This quickly turned to the population explosion that was definitely going to destroy civilization, no later than the distant, futuristic year 2000. They had a computer model called Limits to Growth to prove it, and everybody knows computers are never wrong.

There was Henry Harrison‘s Make Room, Make Room, which predicted we would all be eating Soylent Green no later than, well, now. (“Soylent Green is people!!!,” Charlton Heston hammily informed us.) A few years back, at an East Coast convention, I got the chance to ask Harrison how he got the early 21st century so totally wrong. I expected him to say that he had taken doomsayers, like the always-wrong Paul Ehrlich, too seriously.

But Harrison just laughed and said his book was “pure propaganda“ (his exact words). This raised questions in my mind about the ethics of writing fiction that I have not yet resolved.

The most notable population explosion novel of the time was probably John Brunner’s Stand on Zanzibar, which was great fun and won a Hugo and other major awards. It certainly didn’t hurt Brunner’s career, as a previous comment had it.

On the other hand, Brunner’s next doomsday book, The Sheep Look Up, was dank and depressing and soon went out of print. Air and water pollution will kill us all, no later than the distant, futuristic year 2000 … I guess it still sounds plausible if you’re sufficiently ill-informed, or live in China. (When I was a kid, and my family drove to New York City, we could smell it before we saw it. Since then, they cleaned up the air.)

I guess the general principle to be drawn from these and many other examples is that: the sky isn’t falling. The sky is never falling. It’s simply that activists believe if they don’t exaggerate a problem (real or hypothetical), no one will take the actions they believe desirable.

The late Stephen Jay Gould was very critical of climate doomsayers. If rainfall patterns change, or if sea levels rise, he said, these are very serious problems. But, he continued, when a paleontologist hears global warming doomsday scenarios, he smiles: because he knows how warm the Earth was in some of its most verdant epochs.

I think fiction tends to reinforce existing prejudices, rather than change people’s minds. Also, wide use of global warming as a trope in SF may actually be counterproductive, leading people to dismiss it as just another SF trope, like alien invasion or FTL travel.

I sort of recoil from demands that any fiction take a didactic role – it’s a constraint on creativity and I really don’t believe fiction works that way. Also I feel SF has been dealing with climate change for a very long time – at least as far back as J. G. Ballard, possibly even our most ancient mythologies. I find it strange to suggest that contemporary writers aren’t – obviously Paolo Bacigalupi comes to mind – his The Windup Girl is one of the best, but all the usual suspects have included climate change in their world-building: Kim Stanley Robinson, Stephen Baxter, Margaret Atwood etc.

i agree with Robert (above) that writers should write from the heart and not from a political agenda, but if that writer’s heart favors that political agenda, he/she definitely needs to speak out in his/her works. Science-fiction definitely has a crucial position in literature in that, by its nature, it can speculate on possible futures, thus forming a valuable complement to science, whereas good science is limited to hard, peer-reviewed facts. Science-fiction can speculate on issues or problems that might arise in the future, thus enabling humanity to at least intellectually prepare for disasters well before they arise. Before NASA started tracking comets and asteroids that could destroy Earth, how many books and movies were there that imagined that scenario?

I’d rather have a story set in the future when the climate change threat has been solved. How it was solved could merely be indicated in casual references and features of the environment. There are after all possible solutions, including the Thorium Molten Salt Reactor and Supertorrefaction. Perhaps reference could be made to an extreme event in the past that convinced people that serious action was needed – a Superhurricane destroying Washington D.C. perhaps. But no need to show this or to turn it into a disaster movie; instead, show a world that has benefited from it’s commitment to science, as well as from achieving a fair degree of international cooperation. It is that kind of society, after all, that would be in the best position to do things like terraform Mars and Venus.

No one who values science needs to be convinced by a science fiction movie of the perils of climate change; no one who does not value science is going to be persuaded by a movie.

Not exactly SF but fast moving, raunchy, Bond-like novels are my latest platform for trying to raise awareness about key challenges we confront. My latest, the Hwanung Solution, is about how climate change is impacting on traditional lives in the Arctic, how melting sea ice is opening up new maritime routes, the political and military consequences – mixed up in a story about treasure hunting, love, and resource issues. I am the former CEO of the UK branch of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development. I ‘retired’ in 2014.