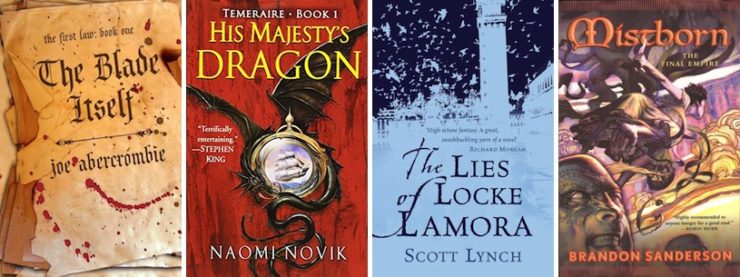

If you’re a fantasy reader (and, if you’re reading this, I suspect you are), 2006 was a vintage year. One for the ages, like 2005 for Bordeaux, or 1994 for Magic: The Gathering. The Class of 2006 includes Joe Abercrombie’s The Blade Itself, Naomi Novik’s His Majesty’s Dragon, Scott Lynch’s The Lies of Locke Lamora and Brandon Sanderson’s Mistborn: The Final Empire. All of which, remarkably, are debuts (except Mistborn, but Elantris was only the year before and Mistborn was the breakout hit, so we’ll roll with it). And hey, if we stretch the strict definition of “2006,” we can even include Patrick Rothfuss’ The Name of the Wind in the mix as well.

These are five authors that have dominated the contemporary fantasy scene, and to think that they all published more or less simultaneously is, well, kind of ridiculous.

However, as tempting as it is to examine the lunar conjunctions of 2006 in the hopes of finding some sort of pattern, the fact that these books all published at the same time is total coincidence—and, in many ways, irrelevant. Publishing ain’t quick, and by 2006, these books had all been finished for some time. For some of these authors, their books had been out on submission for several years. If anything, we’re actually better off prying into 2004, since the process between acquisition and publishing is generally around two years. What was in the air when five different editors all decided to lift these particular manuscripts from the stack?

Or do we go back further? We know, of course, that these books were all written at completely different times. The Name of the Wind was the culmination of a decade’s hard labor, beginning in the 1990s. Mistborn, given Sanderson’s legendary speed, was probably written overnight. But what were the influences of the late 1990s and early 2000s that would’ve led these five different people to all write such amazing, popular books? In the years leading up to 2006, there are some clear trends. These trends may have impacted the authors as they wrote these stunning debuts. They may have influenced the editors as they chose these particular books out of the pile.

Or, of course, they may not have. But where’s the fun in that? So let’s take a look at some of major touchstones of the period:

Harry Potter

From 1997 onward, the world belonged to Harry Potter. And by 2004, five of the books were published and the end of the series was on the horizon. Publishers, as you might expect, were pretty keen to finding the next long-running YA/adult crossover series with a fantasy inflection. Moreover, Potter proved that a big ol’ epic fantasy had huge commercial potential, and could be a massive breakout hit. It also showed that the hoary old tropes—say, coming of age at a wizard school, detailed magic systems, and a villainous Dark Lord—still had plenty of appeal.

The British Invasion

Rowling—deservedly—gets the headlines, but the Brits were everywhere during this period. Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell was one of the breakout hits of 2004, a fantasy that couldn’t be more British if it were served with scones and a gently arched eyebrow. China Miéville collected every major genre award between 2000 and 2004. Looking at the Hugo finalists in from 2000, you can also see Stross, Richard Morgan, Ken MacLeod, Ian McDonald, Iain M. Banks… and that’s just in the Novel category. Seeing so many British authors up for what’s traditionally been a predominantly American award shows that the UK was, well, trending. That could only help inform—or sell—a UK author like Joe Abercrombie, or a British-set novel like Novik’s His Majesty’s Dragon.

A Game of Thrones

This is a little weird to think about—by 2006, every A Song of Ice and Fire book (save A Dance with Dragons) had already been published. The Potter arguments apply here as well—ASoIaF was proof of concept: big fantasy series would sell, and publishers were on the prowl for the “next” one. And, for authors, ASoIaF had dominated the scene since 1996: even before the HBO show, it was a massively popular series. Big Fantasy, again, could be successful—and by subverting the tropes, Martin ushered in a new world of possibilities. Characters could die. Good guys could lose. Surprise was as interesting—and as rewarding—as simply doing the expected.

* * *

But if we simply limit ourselves to books, we’re missing out. A lot. The Class of 2006 was surrounded by storytelling in a host of formats, both personally and professionally. Abercrombie and Novik, for example, worked in the film and the gaming industries, respectively. So let’s also consider the impact of the following:

The Lord of the Rings

The three most successful fantasy films of all time were released in 2001, 2002, and 2003. Everyone knew how to pronounce “po-tay-to” and had an opinion on eagles. The films were ubiquitous, breath-taking and, most of all, lucrative. Jackson’s trilogy meant that Hollywood wouldn’t shy away from Big Fantasy, and, as with Harry Potter, everyone was on the prowl for “what would be next”…

Gaming

The biggest and best fantasy worlds weren’t in cinemas—they were in your home, to be devoured in hundred-hour chunks. 1998 alone saw the release of, among others, Thief, Baldur’s Gate, Half-Life, and The Ocarina of Time. By the early 2000s, games weren’t just hack-and-slash; they were about stealth, storytelling, meandering side-quests and narrative choice—with a rich visual language that stretched the boundaries of the imagination. From Baldur’s Gate 2 (2000) to Final Fantasy (1999-2002), Grand Theft Auto (2002, 2004) to Fable (2004), huge worlds were in, as were immersive stories and moral ambiguity.

Games were no longer about levelling up and acquiring the BFG9000; they involved complex protagonists with unique skills, difficult decisions, and complicated moral outlooks. Whether it’s the immersive environments of Scott Lunch’s Camorr, the unconventional morality of Abercrombie’s Logen Ninefingers, the deliciously over-the-top Allomantic battles in Sanderson’s Mistborn books, or the rich and sprawling world of Novik’s Temeraire, it is easy to find parallels between game worlds and the class of 2006.

The Wire

Television’s best drama started airing on HBO in 2002. Critically acclaimed (and sadly under-viewed), it’s had a huge impact on the nature of storytelling. Big arcs and fragmented narratives were suddenly “in.” Multiple perspectives, complicated plotlines: also in. Immediate payoffs: unnecessary. Moral ambiguity: brilliant. Pre-Netflix, it showed that audiences—and critics—would stick around for intricate long-form storytelling. The Wire’s impact on fiction in all formats can’t be underestimated.

Spice World

In 1998, the Spice Girls had sold 45 million records worldwide. Their first five singles had each reached #1 in the UK. The previous year, they were the most played artist on American radio—and won Favorite Pop Group at the American Music Awards. Yet, later that year, Geri Halliwell split from the group. Sales foundered. Lawsuits abounded. The Spice World had shattered. As an influence, we can see here the entire story of the Class of 2006. The second wave British invasion. The immersive, transmedia storytelling. The embrace of classic tropes (Scary, Sporty, Ginger)—and their aggressive subversion (Posh, Baby). The moral ambiguity—who do you think you are? The tragic, unexpected ending: what is Halliwell’s departure besides the Red Wedding of pop? The void left by their absence—a vacuum that only another massive, commercially-viable, magic-laced fantasy could fill.

* * *

Okay, fine. Probably not that last one.

But it still goes to show the fun—and futility—of trying to track influences. With a bit of creativity, we can draw a line between any two points, however obscure. If anything, the ubiquitous and obvious trends are the most important. We don’t know everything that Rothfuss read or watched while crafting The Name of the Wind, but we can guarantee that he heard the Spice Girls. If a little bit of “2 Become 1” snuck in there… well, who would ever know?

Chasing an author’s influences—or an editor’s—is nearly impossible. There are certainly those inspirations and motivations that they’ll admit to, but there are also many more they don’t. And many, many more that the authors and editors themselves won’t even be fully aware of. We are surrounded by media and influences, from The Wire to BritPop, Harry Potter to the menu at our favourite Italian restaurant. Trying to determine what sticks in our subconscious—much less the subconscious of our favourite author—is an impossible task.

What we do know is that, for whatever reasons, many of which are completely coincidental, 2006 wound up being a remarkable year. Thanks, Spice Girls.

With huge thanks to r/fantasy and /u/TeoKajLibroj for kicking off the conversation.

Jared Shurin is the editor of Pornokitsch and over a dozen anthologies, the latest of which is The Djinn Falls in Love and Other Stories.

Jared Shurin is the editor of Pornokitsch and over a dozen anthologies, the latest of which is The Djinn Falls in Love and Other Stories.

Anecdotally, I’d say there was something in the 2004 air that opened minds to fantasy. It was the year I started reading Lorde of the Rings and Wheel of Time, and they both took over my brain to an unprecedented degree.

I don’t know what age group Harry Potter is officially for, but it’s in the “chidrens’” section of my library for some reason.

Sanderson wasn’t writing things overnight in 2004. He didn’t have his team in place yet. :-D

But luckily, he did already have Isaac Stewart for the maps.

As you said, fantasy had proven itself lucrative, therefore worthy of being published. Thankfully, there were some great authors waiting for their shot. And they nailed the bullseye.

@1: Since Harry starts out at 11 years old, the books will always be considered Middle Grade = Children’s section. Despite the fact that as Harry grew up, the books became darker.

Okay, I’m going to be That Guy.

While it’s pretty arguable that Final Fantasy was hitting its peak from 1999-2002, publishing a game a year with each of them being huge commercial successes, the franchise started in 1987 and is still going today – Final Fantasy XV was released last November, and the next expansion to the second MMORPG, FFXIV, is out next Saturday.

So I’m not the only one who noticed. I remember that is the year I went from; desperately searching for books I want to read and having I big gaps between reading sci-fi/fantasy novels, to having to make hard decisions between which book of several, I wanted to read next.

Interesting article Jared. I would add a couple of others:

Wheel of Time was also at around peek popularity at that time, and likely a broader influence than A Song of Ice and Fire (or Game of Thrones as people call it now). For example, we know that Wheel of Time was hugely important as an influence to Sanderson.

But, more importantly, I think that the internet and various precursors to social media also played a huge role. That was the hey day of message boards and there were even list serves still around. Many of those who were wrote the books that came out in 2006 were inspired by these early online experiences (most of us over the age of 40 or so dived into the fan part of the internet in the late 1990s and early 2000s), and these publications culminating in 2006 is no coincidence given the typical lead time for publishing. It’s the same reason why so many blogs were coming online at the same time (my own started in early 2006). This was the time when the ‘fan reviewer’ was really starting to hit mainstream and publishing houses were starting to take notice.

Ironically, it was probably Jaq D. Hawkins with her Goblin Trilogy in 2005 who might have started new interest in Epic Fantasy. Maybe she should have sent it to Tor.

This was a fun bit of nostalgia – 2005/2006 was the year I graduated from college, and my first year of graduate school, and while Sanderson (and Rothfuss) are the only authors in this group I’ve read, I didn’t actually get to either of them (or Martin, for that matter) until well after they had initially published their works. I got into Sanderson (like most, perhaps) when it was announced he would finish WoT, and Rothfuss when the second book came out (I went to a signing with some friends who were big fans of the first book). Fun fact, GRRM came to a small Madison sci-fi/fantasy convention in 2008 (it was right when I had started my new job after leaving grad school). I hadn’t read any of his books either, but had heard good things…and if I recall this was about when buzz about a TV show deal had come about, but before he was a mega star in the wider world. So I got to have a more intimate fan experience than perhaps you would get now (I recall being in a room with just a few other people towards the end of the convention basically just shooting the shit with him).

Even Harry Potter I didn’t get into until after the 4th book came out (I was a senior in high school and had mostly ignored the phenomenon as for kids until I noticed a friend whose taste I respected reading them). And I can’t really be blamed for this given my age, but I didn’t learn about Wheel of Time until my German teacher lent me the first book my junior year in high school (1999)…at that point I think up to Path of Daggers was published. So I guess I’m always doomed to be getting into things secondhand, probably because I’m always trying to play catch up with the stuff that’s already out!

The Spice Girls thing had me laughing out loud. (Funny conicidence, for shits and giggles I put on a 90s nostalgia station and a Spice Girls song was the first one on, hehe).

I think Star Wars could possibly be another thing going around – whatever your opinion on the special editions/prequels, from 1997-2005, Star Wars movies were a big thing (if I recall, people worried that the re-release of the Special Editions would basically just be a dud and show that nobody really cared about Star Wars anymore but were proven completely wrong), and the EU also experienced a resurgence. Star Wars was my first exposure to things like midnight premiers, going to a movie in costume, etc. Now people even do stuff like this for book releases!

And more to this point of this article – I definitely found that the fist half of the 2000s (well, and beyond) was a kind of sweet spot were suddenly being a geek was cool – it was perfectly acceptable to be geeking out about Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter and stuff like that. And heck, in 2005 is also when Weird Al came out with White and Nerdy and I remember that going quite viral (I am a lifelong Weird Al fan, and I remember when Straight Outta Lynwood came out, all of a sudden there were all of these ‘serious’ music analysts taking him seriously as a cultural influence whereas before he’d kind of been dismissed as a novelty) and a lot of analysis about nerd culture, etc.

Of course that’s also when I was in college/grad school so perhaps also had more exposure to fandom in general – that’s also when I started getting introduced to Neil Gaiman I think. So like somebody above points out, the market was now ripe and these authors were there at the right time (Brandon Sanderson had several books already written by the time he actually got one published, basically waiting for his break).

There terrorists attacks on 9/11 may have also played a factor. From what I understand books sales hit an all time low after 9/11, didn’t they? Not sure when sales recovered,but maybe it was around 2005/2006.