Ah, love. A many splendored thing. Here is a rather unusual love story, sweet and strange as could only happen in the post-magical reality of the Indigo Springs “event.” Blue Magic, the sequel to Indigo Springs was published in April and here's a tasty tale from that world to tickle a reader's fancy.

This short story was edited and acquired for Tor.com by Tor Books editor Jim Frenkel.

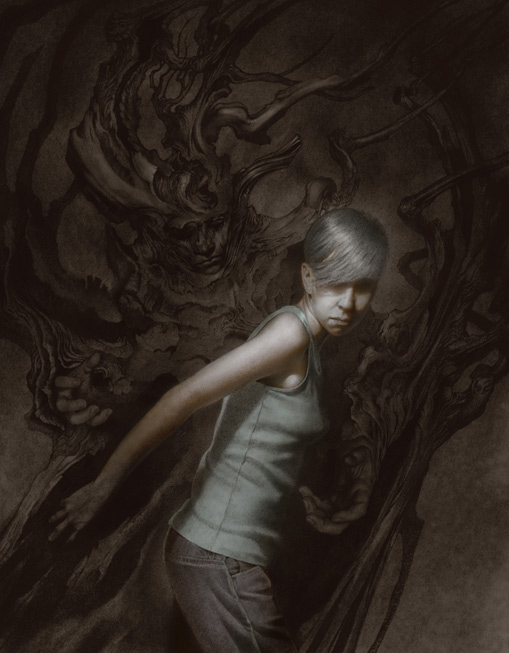

My swamp man wasn’t what you’d call a sexy beast, though I found his skin strangely beautiful. It was birch bark: tender, onion-thin, chalk white in color, with hints of almond and apricot. He was easily bruised, attracted lichens, and when he got too dry, he peeled.

Instead of hair, he grew whisper-thin stems. Every morning we made a ritual of shaving his scalp, breaking those new-grown shoots. Once when time got away from us and they were left to grow a couple days, he broke out in catkins, a crown of fuzzy, pollen-laden locks of gold.

He was always cold. I had to keep him out of the rain so he wouldn’t dissolve into the ecosystem, rooting in whatever soil was closest, erupting in clumps of moss while salmonberry runners snagged him, tearing him with their thorns. The bog (and Vancouver is surprisingly boggy, though you might not think it) wanted him back.

But when it was dry and summer-hot, Aidan stood with a man’s firmness and spoke with a voice deep as a drum, and he could almost pass for normal.

I first saw him standing in a streamer of dawn mist rising off the surface of Burnaby Lake.

I was running a loop around the park, fighting to pass the fitness exam for a job I wasn’t sure I wanted anymore, one my lungs had about given up on. I was gasping for wind on a narrow stub of beach when I spotted him, still as a stump in the slate water, thigh deep and surrounded by paddling mallards and their ducklings. The sun had only just crested the treetops behind him and he was just a well-formed shadow.

Wheezing, I raised my phone, taking a snap for Cutemeat. The blog was my friend June’s idea: join an online community, she’d said, show that department-appointed therapist you’re still interested in boys. Sign of mental health, right?

“Adonis, fishing without a pole,” I captioned the shot, hitting SEND.

Then I thought: And without hip waders. Isn’t he cold?

I looked closely. No sign of rubber boots or any other water gear. I squirmed involuntarily, imagining cold water lapping at the join of his legs.

The sunlight brightened and I realized I was looking at his bare ass. The phone bleeped, loudly, to say it had sent the photo. Startled, I dropped it on the sand.

“Don’t be afraid.” Bass voice, fog-cool, lapped across the lake. “Please . . . ma’am . . .”

Just when did I become a ma’am?I scrabbled for a hefty branch, in case he came after me with a machete.

A machete hidden where? He’s got no pants!

But it had all been an illusion. As the mist gusted away I saw his limbs were wood, his nose a curl of bark. The ducks were gone.

“Who said that?” I shouted. The sound vanished into the brush.

I circled, club raised, then retrieved the phone, checking to see if someone had called, trying to explain the trick. But no. Apparently I was having a nervous breakdown.

Or was I? A year earlier, a couple witches in Oregon had spilled (or unveiled or unleashed, depending on whose spin you were buying) magic into the U.S. Actual friggin’ magic, as June puts it: flying carpets, people wielding lightning bolts, monster fish in Puget Sound, the whole nine yards. Mount St. Helens erupted and terrorist wizards sank a U.S. aircraft carrier. The forest north of Portland overgrew and jammed up with trees—weird, enchanted, supertall trees—and monsters too.

But Canada was supposed to be mostly clean: the government had gone to the expense of posting signs at Burnaby Lake, promising it was safe.

Would it be better if I was insane?

Maybe we were all a little crazy now. Last Christmas our biggest problems had been climate change, the recession, and war in the Middle East. Now it was glowing rabid raccoons sneaking around Seattle, magic-wielding cults fighting the FBI, refugees, missing persons by the thousands, tsunamis, hurricanes, volcanic eruptions, quakes in the news every week, and people turning into animals.

Plusclimate change, war, and an even worse recession.

I ran on. By the time I’d got as far as Piper Spit, it was obvious something was wrong with my phone. Sap caked the memory card slot, and the whole thing was cold, cold enough that water beaded on it, running down the screen. I pulled it apart, extracting the card, disconnecting the battery, and giving all the pieces a fierce rub with toilet paper cadged from the bathroom at the nature center. The sap tore at the tissue while sticking the paper to the phone itself. All I achieved was getting goo and paper stuck in the burn scars on my palms.

Magic it is, I thought. I stuffed the bits of the phone in my day pack, then shared out my granola bar with the ducks, starlings, and Canada geese mooching after handouts on Piper Spit. There were a couple of birders out with big cameras, seated under little neoprene sheets of camouflage-patterned plastic, breath puffing as they waited, waited, for the perfect shot to come along.

I picked at the sap on my palms, in the scars.

“Okay, this is good. It’s better if it’s magic,” I told the birds. “I can still pass that physical, show the doctor I got mental health by the truckload and a strong libido too, and get back into the firehouse.”

They scrabbled at my feet, in single-minded pursuit of my crumbs.

“Sometimes I ask myself, why do I feel this way? Why does it feel like my heart’s beating for us both? What’s this tie between us I can’t imagine cutting?”

“I wonder why you feel this way too,” Aidan said, in his syrupy Georgia drawl. “Lovin’ someone with my limitations . . .”

“I hate it when you get all ‘I don’t deserve you.’”

“Just not sure I do,” he said.

“Everyone has limitations,” I said—that much, I knew for sure. “Everyone’s a lot of work.”

“One good pourdown and I may yet fall apart. I get chilled, I stiffen up—”

“I’ll try to keep you warm.”

“I’ve got no papers, Calla, I’m in the country illegally. I should be under magical quarantine.”

“Shut up,” I replied. I’d man-napped him away from the bog, to a rented trailer in the heart of wine country, in the desert town of Oliver, near Lake Okanagan. Fleeing east down the highway, a six-hour drive from Vancouver, to a climate where it was drier and hotter and hopefully safer, had seemed like a great idea at the time. “Anyway, I’m contaminated now too.”

“Because of me.”

I waved that off. “My point is: why you? Why you and me, why this thing? We’ve both had lovers before. We worked at it, I know. When it ended, all those other times, I didn’t shrug it off, did you?”

“No, you’re right. I’ve had my heart broke.”

“I never had this feeling before, that cheesy teen romance thing where if you died, I feel like I would too. I’m a practical person, not some doe-eyed movie heroine.”

It was almost dawn. Aidan had found work making buns and custard cakes in the scorching heat, cash under the table, in a bakery that purported to be Portuguese. Now he was out on his break, in the alley. We’d missed each other too much to wait the six hours until his shift ended.

He said: “Maybe the clichés were true all along. Maybe there is one perfect soul mate for everyone.”

“Not a bunch of people who’ll do?”

“I didn’t believe either—I was a scientist, Calla.” He pulled me close and my heart trip-hammered. He had come straight from the kitchen, and his skin lacked its usual chill. He was almost as warm as a man. “Love at first sight . . . I never bought into that.”

“Maybe it wasn’t true all along,” I said. “Maybe when all that horror-movie stuff escaped near Portland, fairy-tale things came too—”

“Things,” he teased.

“Love at first sight, like you said.” I poked him in what should have been his ribs. “Someday my damn prince will come.”

“One glass slipper, one foot to fit? Happily ever after?”

Nose to nose, we giggled nervously. If we got caught we’d be separated, locked away just for being freaks. Maybe all this nigh-painful joy was just the knife edge of secrecy, the intensity of being cut off from normal life. We had to be everything to each other; we couldn’t trust anyone else. “We’re not Cinderella and Prince Charming, Aidan. More . . . Bonnie and Clyde.”

“Without the guns,” he said, and I found myself wishing he’d denied it. “Thelma and Louise.”

“Without the big kersplat?”

“Let’s hope.” He kissed me and I savored those lips, that warmth. “My break’s over.”

One more squeeze and he was gone, with a blast of hot air from the baking ovens and the clang of a fire door. I was alone in the alley with a couple of hopeful, garbage-seeking grackles and my thoughts, which tended to the grim.

My swamp man made love more or less as a man did. He was shaped right, even if the feel of him against my skin lacked an animal’s heat. I had to learn not to bite him, ever, because the marks lasted for weeks, and the acrid tang of plant juice on my tongue was too much of a reminder of how far removed from human he had become.

I couldn’t think about his swampy self, about what he was like in the rain. Instead I watched his face as I moved over him, his expressions twisting in normal, undignified, apelike contortions of pleasure. He groaned and shuddered and came like any man, and sometimes when he did, there was a rush of sound, wind through poplar leaves, and I’d feel something titanic, an internal battering wind, irresistible, pleasure so intense it was as though it might fling me across the room. I’d feel him and me, locked around each other, and our problems became as ephemeral as tissue paper.

Also, he wasn’t uptight: he let me name that part of him Woody.

We kept to ourselves out of necessity, playing hermit to protect our secret, and so we made love a lot. Our days in the desert were sex and TV, book reading and naps, walks together in the heat, sleeping odd hours and as much cash work as we could get. Warmth and sunshine for him, food for me, all the money we could squirrel away. We were always poised to flee: cash in the truck, a packed suitcase, full tank of gas and the endless speculating. Where next?

“Alberta’s dry,” he said one day as we were strolling through an orchard, six-foot trees laden with green, rock-hard apricots.

“The winters are cold,” I said. “You’ll stiffen up.”

“You’ll keep me warm.”

“If I can.”

“We don’t know that you’ll hibernate.”

“We don’t know that I won’t. We should try to get into the States, Aidan. Hotter country and more people to hide among. A whole culture of illegal migrants. I could be someone’s nanny.”

“How would you get me through the border?” He was American, but he was on the missing list. The bog, ever a jealous lover, had eaten his ID along with his clothes and his research team.

“I’ve already seen the Prairies. I want—”

“Just one winter. Longer we’re loose, the better our chances are,” he said. This was his mantra, that thread of hope I didn’t quite believe in. If the mystical apocalypse kept getting worse, he thought, governments might run out of resources for chasing those of us who’d been contaminated by magic.

I took a long whiff of the sandy air, trying to dry the tears that threatened whenever we had these conversations. As long as we didn’t look at it square, I wasn’t unhappy. When we did, I got to thinking: is it really going to be marginal jobs and fear of the cops and the packed truck ready to go, for as long as we live?

Aidan must have sensed the storm building in me, because he changed the subject. “What happened that day in Vancouver? The day you lit out for here? You’d kicked me out of your place, told me to get lost. Why’d you change your mind?”

“I can’t get out of the habit of rescuing people?”

“Don’t be glib.” He adjusted his glasses on his nose; he didn’t need them anymore, but somehow he’d hung on to them through it all: they were the only past he had left.

I thought back to the storm: standing on my back porch with a paper birthday hat melting on my head in all that warm, pouring rain. Aidan had been hunched in a corner, semiconscious, obviously hurting. Cedars and maple saplings were sprouting on his legs, using him as a nurse tree. Black slugs and leopard slugs pooled in his elbows and in the hollow of his neck. A stack of shelf fungus was fluting out on his rib cage.

It was an unsettling, unpleasant memory; this was what I screwed every day, after all, this guy who just needed a good soaker to reduce him to a spongy mass of rotten vegetation.

If I’d left him where he was that night, he’d be gone, absorbed back into a forest that wanted its mind back.

“Calla?”

“I was trying to get back on the job. There was the physical stuff, with my lungs.”

“Which are improving.”

“Love heals,” I said.

“Not the dry air? Or the magical contamination?”

“Love,” I insisted. “There was this physical I had to pass, and the therapist with her questions. Why’d I go into that building again when I knew it was unsafe, why did I risk myself and the guys from my firehouse? How’d I feel about the civilian dying? Civilian, she’d say, like he wasn’t even a person. How’d I feel about being burned? She seemed to think I needed friends and hobbies . . .”

“Friends and hobbies and a normal life?” he asked, a little wistfully.

“It was stupid, I told her. Plenty of time to putter in the garden and go for drinks with the guys: give me my job back. Who am I if I’m not a firefighter?”

“Who are you now? A fugitive.”

“I’m yours.” I wrapped my arms around him, locking eyes until the sadness went, until he nodded that I should go on with the tale.

“You kissed me, Aidan, and we argued. You didn’t square with getting my job back, and I was scared. So I forced myself to tell you to clear off.”

“You stormed out,” he remembered. “‘Be gone ’fore I’m back from physio,’ you hollered.”

I’d never made it to the physiotherapist’s: I’d gone down the road to the public library, locked myself in the women’s bathroom and sobbed until they kicked me out. Instead of telling him that, I said: “My friend June had hatched this plan to show my shrink I had a social life on the go. A surprise party, for my birthday. She’d been waiting for me to leave for physio.”

“She had a key to your place.” Aidan nodded. “I was about to leave when she came into the house with a dozen people. The decorating committee for the birthday party. I had to sneak upstairs.”

He’d been cowering in the closet when I finally made it up there, hours later. Safe enough, but miserable. And I was so relieved. “Don’t go, don’t leave, I’m sorry,” I had begged him, and we ended up necking like horny teenagers. I remember that crazed teen romance part of me thinking it was capital-D Destiny, that June had saved me from a terrible mistake.

Destiny was nosy. She set me to cutting a cake and went up to investigate what her guest of honor had gotten up to. It all turned a bit French farce, after that: Aidan had to climb out the window and down to the porch to escape her, and that’s when it started to pour.

“But what happened at the party?” He repeated. “What happened between our fight in the afternoon and when you came upstairs? What changed your mind about getting rid of me?”

“I realized all those people I used to know . . . they were looking for the old me, the Calla from before the fire. Maybe even the Calla before my dad passed away and Richard dumped me, the me from before the magic spilled out and the world started circling the bowl—”

“Those people cared about you.”

“You love me,” I said. “You.”

“They didn’t?”

“Whoever it was they loved, she’d burned away. I pretended to be that woman they’d known, for two hours. For me, too, not just for them. I had to know: could I do it? Just two short hours. But it was like walking in boots that didn’t fit anymore. It rubbed me raw; it hurt, every step hurt. My lungs were full of steel pins. So I sent them home and scraped you off my porch.”

“It wasn’t about loving me, then. It was about being done with your old life.”

“What is this, insecurity? I wanted you to live,” I told him. “I’d fallen for you. Love at first sight and you die, I die and all that magical bullshit, remember? It is mutual?”

“It’s mutual.” He pressed his wide, cold hand to my chest, feeling my pulse between our joined skins. “I love you.”

“It’s enough,” I told him. “It’s gotta be.”

We sprinted back to the trailer and jumped into bed. All the talking in the world wouldn’t change the situation. We were sometimes tired, we were often scared, there were rewards out for anyone who turned in the contaminated, and the world, for all we knew, was ending. The two of us and everyone else, we were all just pretending to believe we still had a future.

Sex at least was here and now. Joy and love and shaking the trailer until we were spent, post-coital giggles and pillow fights drove it all back to a manageable distance. For a while, anyway.

It was the first time I moved Aidan that I got magically contaminated.

He’d come home with me from the lake, inside the phone’s memory chip. I’d captured the picture and he had got in there, and then, like a sprout, he’d grown. By the time I’d showered off my run, he was lying on my kitchen floor, in the shredded remains of my day pack, buck naked, fetal, immobile as a statue, and with water condensing all over his birchy skin.

I’d heaved him across the house and into the tub, thinking he could drain there. He fell in face first, his butt pointed up at the ceiling. I meant to call the police, but even so I couldn’t leave him that way. It was undignified; it felt cruel.

So I reached into the tub, wheezing with the effort I’d already made, and tried wrangling him over, onto his side or sort of sitting. I was pulling on his feet—I didn’t want to grab the obvious handhold near his center of gravity. Awkward, slippery fumbling in a close space, and all of it made harder by the thick, numb scar tissue on my palms. By the time I had him flipped upright, I was soaked in sweat . . .

. . . and my hands itched.

Know how a hot dog looks after it’s been skewered and stuck in a campfire? The red, burned meat, the seared brown-black blisters? I made a point, in those days, of not looking at my palms much. Other people stared when I went out; I refused to wear gloves, to hide. But I was something of a genius at getting through the days without looking at the burns myself.

Naturally, this was another thing the therapist had an issue with.

(After we ran, the story I gave out about my hands was half the truth: I told people I was a firefighter, told them I got burned doing a rescue. But I also said I saved the guy, that it was Aidan, and that his weird pale skin was grafts. I’d give them a good look at my scorched-sausage palms and say, “And then we fell in love.”

“Awww,” these strangers would reply. Everyone loves a romance, right? So far, nobody’d turned us in.)

Anyway, the hands—I’d moved him and they itched. I took a good look.

It was splinters, driven into the burns. They were lined up like little dominos, bristles driven in to the lines of my hand, life line, heart line, brain line . . . all the grooves where palm readers look for meaning. Tiny spiked fences of bristling birch, dividing my hands into mapped terrain, lumps of territory, each filament barely aglow with the blue that had come to mean magic.

“Go to jail,” I whispered. “Go directly to jail. Do not pass go.”

Behind me, someone answered, in a voice so deep it vibrated my bathroom mirror: “Ma’am? May ah have some pants, please?”

My best cash job that summer was delivering concrete statues to people who wanted Italian Cupids or ornate birdbaths or what-have-you on their front lawns. My boss, Vitaly, claimed to ship them from whatever country the designs nominally originated in, but he really cast and painted them in his garage. All very authentic, he was fond of saying. He pronounced it “Aww Thenn Teek.”

It was a good gig. I drove all the back roads, coming to know offbeat ways to get from town to park to vineyard, identifying a dozen isolated spots where Aidan and I might hide if a manhunt broke out.

When he wasn’t at the bakery, I’d bring my swamp man along. We turned off the AC, letting the cab of the truck heat up. I swigged water and sweated as the sun baked in. The almond tint in his birch-bark skin came out and he looked as human as anyone. We’d pretend-fight over music as we drove around the little British Columbia locales with their funny names: Osoyoos, Penticton, the Naramata Bench.

We explored the Similkameen, delivering jumped-up lawn dwarves, the occasional Buddha or Ganesha, once even an Easter Island head the size of a ten-year-old boy. The vineyards and orchards spread out on either side of the highway, cultivated land in patchwork arrangements, divided by fences. It rolled down to the powder-blue waters of Okanagan Lake—which was supposed to be home to a monster, Ogopogo, they called it, sort of a Canadian Loch Ness monster, a tale from before magic broke into the world.

I wondered about Ogopogo when I had nothing else to keep my mind off my problems. Was it there before the magic escaped? Was there one now? Sea monsters had been sinking ships in the Pacific since the magical outbreak in Oregon.

Was Ogopogo alone, or did it have a mate?

Our best conversations happened on those long stretches in the truck. I’d pick a random childhood memory: my favorite book when I was ten, the first movie I saw in a theater, some toy I got for a Christmas present.

Once: “When I was a kid, my mother bought jelly in cans.”

Aidan busted out grinning. “Yeah. There was a plastic lid on the bottom of the can, for once it was opened—”

“Like for canned coffee. And you used a can opener.”

“The jam would have these grooves from the can lid,” he replied.

“Like circles in a pool of water, but frozen in place, and full of fruit seeds. I liked raspberry.”

“Strawberry for me.” He drummed his fingers on the dash, keeping time with his clangy Nicaraguan jazz. “You could get those circles with coffee, too, if you opened the can carefully enough.”

“Yeah, and then trace them with your finger until the machine pattern disappeared, and it was just like sand, with finger-circles.”

We loved finding these little ‘before’ things we had in common. Like the fact that we both studied Sparta in grade four. We’d both tried and failed to get our mothers to buy us Cap’n Crunch—too much sugar, was their ruling. We’d both collected soup labels for a while, to mail in for some prize neither of us could remember getting, and sold magazine subscriptions—unsuccessfully—for school fundraisers.

Nostalgia, I concluded, after the coffee can conversation ended with us screwing madly in the back of the truck, next to a full-sized concrete Roman warrior swaddled in bubble wrap, had become some kind of aphrodisiac.

One of our grim little in-jokes is that the bog loves Aidan for his mind.

“Spill it,” I’d said, that first day, after I got him out of the bathtub and into a discarded pair of Richard’s pants and a Vancouver Fire Department T-shirt. “What happened to you?”

“I got caught in the magical outbreak, in Oregon.”

“You’re one of the missing townspeople?”

“Not a local. I am—well, I was a biologist.”

“A scientist?” It was stupidly thrilling just to be near him; I hadn’t felt like this since I’d had a pointless crush on my grade six social studies teacher. He could have been talking about the War of 1812 and I would have been riveted. That I managed to say, “Go on,” and not, “Do me now!” was something of a miracle.

But he was magic. Contaminated. He had to go, or I’d never get my old life back.

“We’d camped on the edge of a riparian zone, taking DNA samples. We’re—we were—building a taxonomy database. Three of us: me, Debbie, Ian. Then Debbie didn’t come back from the weekly food run to Indigo Springs. When we realized she was hours overdue I decided we should go out, trace her steps, report her missing if need be.”

“We were packing up, and the quake walloped us. Trees fell across the path, there were aftershocks, and naturally we lit out for town. We couldn’t know that was the epicenter. After sunset, we were blind. The magic was changing everything, the trees were getting bigger, and the wildlife—”

He rubbed his face. “Pitch black, the sounds . . . and we realized all the animals who could were fleeing past us, running away from the direction we had taken. But then I pitched off the edge of the trail and into an ice-cold pool. I swallowed—I all but drowned. I scraped myself on all sorts of things, and a birch branch stabbed through my forearm . . .”

I remembered holding on to the burning man as long as I could. They’d had to force me to let go; one of the guys from the firehouse almost broke my wrist. It was the day after we’d found out that magic existed and I’d been so scared and angry.

As Aidan talked I pulled the blue splinters out of the meat of my palm, leaving dotted lines like tattoos among the burn scars.

“Ian called my name, for a while,” Aidan said. “Until somethin’ scared him. He ran, and I tried to follow. I thought I did follow, in some fashion. I could hear him. I was beside him or with him. But it was all a muddle. I was in the forest, becoming tangled with it, and it was as if the trees and ferns and all the little birds were watching Ian, and I was within them . . .”

“He died?”

“There was an ants’ nest. Big, magically contaminated ants. They tore him apart while the rain forest watched . . . ” His hands drifted up, as if to cover his ears.

To block out the memory of screaming, I thought. I held up my scorched, punctured palm. “I saw a man burn to death that same day. It was slow. I couldn’t help.”

He reached out with just a fingertip, tracing my heart line. We stared into each other’s eyes, dizzy, voltage building between us, until it was break apart or kiss. I knew there was no way, no way at all, I’d ever call the cops on him.

He’s gotta go, I thought again. Keep your lips to yourself, Calla.

Finally he closed his eyes and drew back, saying, “I’ve been woven into the rain forest ever since. Diffused. Watching, growing, spread thin.”

“We’re hundreds of miles from Oregon.”

“An ecosystem is one big body, just as a person’s a big collection of cells. I gathered in that lake, more of myself every day, caught somehow near a swirl of lilies by the dam. I found my glasses on the lake bottom and grabbed on to a birch stump. It’s taken months to be me again, Calla. And this morning, I felt something separate, a part of me that wasn’t tied to it all, a way out—”

“The picture I took?”

Aidan stared out at my yard. Salmonberry canes were growing against the door, extending long thorns around its frame. It was crazy, but we could both sense they wanted to get in. “It wants me back. I might be better off if I go to the authorities—they’d put me in a plastic room; it might be safe.”

“Safe,” I said glumly, looking at my palm. “If what you’re saying’s true, the whole Pacific Northwest is . . . ?”

“Saturated with magic,” he said. “Every leaf, every tree, every rat, bug, and starling.”

“Nobody knows?”

“Government must know,” he said. “They just can’t admit.”

It was all I could do not to put my arms around him. “Don’t worry,” I said. “I don’t keep plants or pets. We’re the only things alive in here.”

Like most of the contaminated, I was devolving into an animal.

The process started with my nose.

I was allergic to dust and pollen as a kid, and both my parents smoked. I’d never thought I had much of a sense of smell, even after I left home. But that day I fled with Aidan, a whole World of Stink flowered out to find me. An hour after I’d driven off, outstripping the chronic gridlock of the suburbs, I started picking up the faint whiff of oil in the AC, the ghost of a dog Richard had taken with him nine months earlier, when he left me, and the salt and oil in a bag of chips wedged under the backseat.

I smelled blackberries ripening on the side of the highway and had to fight an urge to pull over. Because that was the other thing: I was hungry. The last thing I’d done before leaving Vancouver was eat everything remaining in my fridge, finishing with the six leftover squares of June’s birthday cake.

When I parked at a highway rest stop, I got my first mind-blowing, heady whiff of fresh salmon. I felt my entire body lurch at it, ravenous, straining to grab, to eat it raw, to eat it all.

So, I’d thought, digging out my wallet and making for the vendor, who was selling fish burgers out of a big white catering van. I’m a bear.

I got strong too—scarily strong—over the weeks that followed. It made it easy to wrangle Vitaly’s concrete monuments onto and off of the dolly I carried in my truck.

The smell thing I was fine with; the strength too. But bears live to pack on the fat in the summer and snooze through the winter. What was Aidan thinking when he said we should move to Alberta? The cold and dark would slow his sap, and I’d be under the covers, dreaming and belching fish. We’d be helpless; anyone might come for us.

One of the few people I did repeat deliveries to was a woman who ran a funk and antique store in Osoyoos—she seemed to like having one concrete albatross in stock at any given time. I supposed she must have sold them; she reordered, maybe one every two to three weeks. She’s the one who told me that technically the South Okanagan wasn’t a desert—it got an inch or two too much rain, each year.

My swamp man said ecosystems didn’t have tidy boundaries: they blurred. Wine country lacked the lush wet of Vancouver—no ferns, no squash of cedar mulch underfoot, no Emily Carr landscape with its filtered green light and heavy blankets of blue spruce vegetation. The desert landscape verged on Georgia O’Keeffe: sagebrush, trembling aspen, and ponderosa pine, the latter dying by the thousands as an infestation of pine beetles—not magical, a disaster predating the current crisis, but still going strong—gnawed its way through the province.

But animals weren’t ruled by neat climate-zone borders on human maps. Maybe the coast didn’t have rattlesnakes or praying mantises or wild mountain sheep, but the sky was all one piece, and within it the osprey hunted from the sea to the vineyards and beyond. Under it, salmon made the long voyage inland from the ocean every year. Honeybees and bumblebees spread pollen like messages, from plant to plant and province to province, crossing the border without regard for our rules, our guards, and our guns.

So we got found, of course; it had only ever been a matter of time. But it wasn’t the police who came for Aidan.

In the hollow on the acreage where our rented trailer was parked, it started to rain, water pounding like a thousand ball bearings on the roof one night when we were screwing. The storm continued through to the dawn. The locals called it a cloudburst at first, welcoming the break from the thirty-five degree heat. But then it went on, growing from anomaly to nuisance to, ominously, a threat to the harvest. People stared at the skies, muttering about grapes and hang time and mudslides.

Even then, we didn’t realize what it meant. As lightning pounded and crashed overhead, Aidan went to the bakery in rubber boots and a slicker, and I thought nothing had changed but the weather.

Vitaly called and I drove to his workshop, crawling the highway at thirty miles an hour, headlights on, windshield wipers squeaking in vain. He was waiting under an umbrella, beside a concrete rendering of a scantily clad nymph with a big bird in her arms.

“What do you think?” he said.

“Leda and the swan, I assume?” The bird looked less like it was nuzzling her affectionately and more like it might be about to bite her ear off.

“Met a guy online who’s using the magical outbreak as an excuse to develop a Greek temple. Says the old gods are coming back to get us.”

I laughed. Then I thought: Oh, shit, what if they are?

Vitaly thrust a bigger-than-usual wedge of paper at me. “Shipping forms.”

I scanned them. “In the States?”

He shrugged. “You said you had ID. Is it a problem?”

“I can get through the border,” I said. The papers were import documents, all legitimate enough, though Vitaly’d filled the forms out by hand with green ink. There was space on the grid for more entries.

“So?”

I wrapped the papers in plastic, carefully, to keep out the water. “Tell me one thing.”

“Yeah?”

“It is actually statues I’ve been delivering all this time? They aren’t full of pot?”

He howled laughter into the downpour. “I’m a net consumer, Calla—not a producer. I’d smoke myself silly in a week if I was dealing. ’Sides, I’m too old for adventures in cross-border smuggling. You won’t get arrested, I swear.”

“Okay.”

“Not on my account, anyway.”

“Okay,” I said again. “Can you pay me in U.S. this time? So I have money to buy . . . whatever, while I’m there?”

He nodded and fished in the unlocked cupboard in his garage for a few bills. “So we’re good?”

“We’re great.” I was so excited I’d almost broken a sweat.

I drove to the nearest greasy spoon, bought four double burgers, ate them one after another as I made for home. I found the trailer in a growing puddle, the sodden sagebrush and prickly pear of our yard looking like it was fixing to gasp and drown. A flock of maybe seventy Canada geese and their newly fledged young were waiting, staring intensely at the trailer. They hissed at me as I passed.

“He’s mine,” I told them. “You can’t have him.”

Aidan was inside with the heat on and the stove running all four burners, watching the birds watch him.

“At least it’s not the police,” he said weakly.

I didn’t point out that the bog was bigger than the cops. “I say this qualifies as not getting away with it anymore.”

“Yeah. So . . . Alberta?”

I shook off the water, drying my hands over the burners. “I want to go to the States, Clyde.”

“You’ll get snagged trying to save me,” he said. “I’m not worth it.”

“You are precious like rubies,” I said. “But it’s not just about saving you. I want to go south. I’ve seen the Prairies, and winter frightens me.”

“You don’t know that you’ll hibernate,” he said.

“If we go toward the cold, I will. I know it.”

“So we exploit that. Find somewhere to hole up for the winter, ride out the weather in a shared coma.” He cupped my face in his hands. “You know I love to sleep with you.”

“That sounds like a great way to wake up in custody,” I said. “Aidan, even if we don’t get grabbed, even if the world doesn’t end before spring, there’s always an end. That same ticking clock, am I right?”

His pale lips were set, a mulish expression.

“I want time with you. I don’t want to spend it unconscious in some moldy rented basement. I want to see adobe houses and a Civil War battlefield or the Bonneville Salt Flats. Even the friggin’ Alamo would do.”

“I want to give you that, Calla. I love you; I want to give you whatever you want.” He couldn’t quite hold his temper. “But I have no goddamned passport, and the border ain’t some joke.”

“You don’t have to give me squat.” I shut off the burners. “I’ve worked out a way to get it all by myself. All you have to do is say okay.”

Without the heat, Aidan cooled off quickly—the whole trailer did. The flesh tones leached from his body and his joints stiffened.

Cold bit into me too. Oh, I’d hibernate, all right. Maybe it was psychosomatic, but I was yawning as I brought the truck up to the camper door and stretched the waterproof tarp tight over the back. I pulled out a crate I’d filched from Vitaly (passing up the temptation of his cupboard full of cash) and made Aidan a cozy nest of inert, safe Styrofoam peas. As it got colder and colder, I put on a sweatshirt, then a sweater. My swamp man was moving slowly, as if he’d been drugged. I chugged water; the worse I needed to pee, the less I wanted to sleep.

He sat at the tiny dining table with that look on his face; he was scared.

“It’s going to be okay,” I promised. “We’re gonna get away with it, Bonnie.”

“You’re Bonnie,” he said. “I’m Clyde.”

I kissed him, keeping a space between our bodies, withholding my body heat. “Look,” I said, showing him Vitaly’s import papers. “Item: statue. Description: Leda and the swan. Value: nine hundred dollars U.S. Here’s his tax number and exporter permit and here—”

“. . . is a blank line.” He nodded.

“See? We aren’t gonna bother trying to fake you a passport.”

“I’m goods,” he said, bitterly amused. “How much am I worth?”

“More than nine hundred,” I said.

“Nine hundred and one?”

“We don’t want to look cute. Let’s put . . . Item: statue. Value: nine-fifty.”

“What do we say for a description?”

“Classic man?”

“What does that mean?”

“It means you’re crossing the border with your pants off. How’s that for bold?”

“If they do catch us, it’ll save ’em time when they strip search me.”

“They’re not catching us. How about: Adam in the garden?”

“Because I’m so innocent?” His words came out syrupy; he was getting colder.

“Do we have to capture the essence of your being on the forged smuggling form?”

That got him; he laughed. “We should get me a wine barrel and suspenders.”

“Holy shit. My dad totally had one of those statuettes in his office! Yours too?”

“My uncle. It was gross. The big barrel came off, and—”

“Sproing. There was a smaller wine cask on a spring attached to his crotch. So very hilarious.”

“Maybe the world is ending, but at least the seventies ended first.” He got to his feet, stretched, and began unbuttoning his shirt. “Write Michael—it’s my middle name.”

With that he lay down in the crate and I sat beside him, my hand on his, until he lost consciousness, until he glazed and froze. When he was completely immobile, I took his glasses off and kissed his lips, one last time. Then I packed his limbs ’round with garbage bags, as a last defense against the rain, and nailed down the lid of the crate before opening the camper door.

The bog had other ideas about my grand getaway plan.

The swamp hadn’t been content to rain down a few birds with a guilt-trip. The truck and trailer had sunk farther within the growing puddle, and the birds were doing what they could to help, sitting atop the tarp and the roof of the cab.

“Heeetchchch . . .” Dozens of goose beaks, shoe-black, opened to hiss, revealing bubblegum-colored tongues. They smelled of fresh meat and the promise of a long winter nap.

It wasn’t just birds. Six squirrels were jumping up and down on the roof of the truck, and a row of small brown bats dangled on the tailpipe. The sight of a patrolling skunk gave me pause—getting sprayed would get me noticed at the border. A blacktail deerwas standing in front of the truck, giving me the damn doe eyes. The coyote dug methodically at the sand by my front tires.

“Seriously?” I said. “You’re all staging a sit-in?”

They’d learned this from him, I suspected—Aidan had said he’d been arrested in some logging protests, way back when he was an idealistic student.

“You don’t need his brain back,” I told them. “You learned all you could. You’re doing fine without him.”

The animals stood firm, letting a second defiant hiss from the spokesgeese make the swamp’s position clear.

Go on, they seemed to be saying. Throw him in the back, see if you can pull out of the mire and run over that doe before we tear off the tarp and get a few salmonberry runners into Aidan’s leg.

It damn well loves him too, I thought.

I had one of those hot, three-year-old tantrumy bursts of emotion. Dammit, I want what I want, give me what I want. I’ve lost so much, you’re not stealing him away . . . And it was the big rage, all the long-contained anger and fear in my half-bear heart, spilling out as I drew my first full lungful of air since the fire, pulled it deep into my lungs without the faintest hint of a cough or stabbing cramp, pulled it in and let out a frustrated . . .

. . . Well, if I’d meant it to be anything at all, I suppose it would have been something like: “Aarrrgh!”

What came out was a sustained, ursine bellow. Here I was, crossed by a bunch of damned geese and rodents. I’d lost my job, my friends, my faith in an orderly world where you worked hard and didn’t complain and somehow were taken care of. My humanity itself was in question.

I’d found one thing, one, that more than paid for it and I wasn’t going to lose True Fucking Love to a rain cloud and a bunch of edible, honking birds.

The sound of all that anger, roaring out of me, vibrated my eyeballs. It smacked in to the geese like a physical blow—their little beaks clicked shut, and they recoiled in sync. The coyote shot away from the tire and took up a stance ten feet away, coiled to spring farther if I came out swinging. The skunk vanished into the brush with a pungent fart. The squirrels jumping on the truck froze in midbounce with “Holy shit!” expressions on their faces.

“He’s. Not. Yours,” I shouted, with the last of my breath.

The echo of my voice was coming back at me from across the lake. My throat was raw, and I was hungry, so hungry. The burgers I’d eaten were all burned up. I thought about seizing one of the geese and making a violent sashimi example of it.

Instead I reached back inside the camper, grabbed my crate, and slid Aidan under the sagging tarp, beside Vitaly’s statue of Leda. I bellowed again as I leapt into the six-inch-deep mud beside the truck. The flock burst upward, blasting the air with a hundred wings and leaving behind a slime of half-digested grass plugs. I kicked water at the coyote and it bounced back another five feet, growling.

I stomped to the front of the truck and grabbed the slippery, rain-soaked deer by its unresisting torso.

“Go on, start singing ‘We Shall Overcome,’ I dare you,” I said. I’d never been good at sustaining anger; I was starting to think this was funny, and that was bad, because I hadn’t won yet.

Still, I couldn’t wait to tell Aidan about all this.

I dragged it all the way into the bush and wrangled it so we were nose to nose. “You’re fast, Bambi’s mom,” I said. “You can beat me back to the truck. But if we have to do this twice I am duct-taping your neck to this pine tree here, and you can strangle yourself trying to get loose.”

With that, I stomped back to the truck, engaged the four-wheel drive, and drove myself out of the pocket swamp, spraying water as I fishtailed onto the desert highway.

The rainstorm followed me for sixty miles, past the border—where an indifferent blond Amazon in uniform squinted at the customs paperwork and my passport for all of a nanosecond before waving me through. It chased me past the delivery address, where I left the first statue in the shelter of a half-built replica of a Greek temple whose columns were made of cinder blocks. It poured buckets on me and on the state wilderness area I was fleeing through, sluicing down the windows, gushing along the narrow, twisty roads, overflowing the banks of the shallow ditches. The wind gusted so hard that I could feel the truck rocking on the switchbacks.

I cranked the stereo, found West Side Story, sang along loudly—“I like to be in America, okay by me in uhMAAAREica”—fought to stay on the road, and tried not to think about how hungry I was.

Then I crested a hill and before me and below, through a break in the trees, I saw a little town that had been fixed up so the storefronts all looked like something from a Wild West movie: hitching posts, old-fashioned saloon doors, the whole nine. It was maybe a mile ahead, and there the sun spilled on to the road like gold, a clear demarcation between danger and safety, the nice clean line Aidan said didn’t exist.

Magic, I thought, driving out of the deluge and into summer heat. The hood of the truck steamed.

Warmth was good—it revived me—but I was almost faint with hunger. I checked myself in the mirror, finding no overt signs of bear. I did look a little desperate, capable of eating the first thing I saw; every random smell of things edible, fresh or rotten, even the trash bins, was driving me to tears. I hit a gas station with a car wash and bought a box of Twinkies. Golden sponge cake and crap cream filling; bad nutrition. I knew I should have meat—eggs, fish, beef—but the box had practically screamed at me when I went inside. Sometimes my inner bear, she liked her junk food.

I sat on the back of the truck and unwrapped the first, shoving it deep into my mouth, bracing for disappointment. But the sugar sent a primal surge of pleasure through my body; it was as good as my six-year-old self remembered. It made everything better. I moaned, and the sound was deep and guttural and inhuman.

Nobody heard.

The second one broke in my hand, smearing filling everywhere. I managed not to lick it off. The burns on my hands had darkened to brown, I saw, and the damaged flesh of my palms looked a bit like the pads of animal feet.

One problem at a time, I thought, hosing the thousand plugs of sodden goose shit off my tarp. We were through the border. That was enough for now.

In the coffin-shaped crate beside me, something stirred.

I threw one more Twinkie back, went into the station, peed, and then used Vitaly’s cash to buy all their buffalo jerky and a quart of Coke. Protein and caffeine, brunch of champions. After a second’s thought, I bought a fishing rod too, a license and a can of worms.

Then I went out, patted the crate, and jingled my keys. “Hold on a little longer,” I said, sotto voce. “Gotta find somewhere discreet to unbox you.”

The road was narrow and had no passing lanes, but within half an hour I found a turnout for a campground and drove in, paying for a parking spot by a high, burbling stream under the pines.

“Okay! Either we’re clear or we’re not.” The sky was cloudless and hot. I parked in a patch of sun, opened the crate, and shoved Aidan, as gracefully as I could, so he was lying across the driver’s seat and the passenger side. He was stiff as bone; he might have been dead.

I wasn’t worried.

I chugged all of the Coke and got to work on the jerky as I fumbled the fishing pole together, trying to work out, from the instructions, how to string the line. I could smell fish in the stream, and part of me figured it’d be easier to stand in the water and grab at them with my hands. Who knew if the pole was even right for river fishing?

A meadowlark landed on a branch beside me, and I tensed. But it fluttered a little, settling, and began grooming its feathers.

I had hooked my first worm when I heard the truck door opening. World music twanged out; Aidan had turned off my show tunes.

“I bet you know how to fish,” I said, without turning around. I tossed the line in the water. If there were nuances beyond that, I didn’t know them.

“If this is the alternative, I’m willing to help you figure it out,” he replied. He had a wrapped Twinkie in one hand and a pair of green camouflage pants in the other. I’d been afraid to pack much in the way of clothing for either of us, in case the truck got searched.

I gestured at the stump across from the fire pit, inviting him to sit. “My grandma was a Twinkie fiend. She always had a box in the house. If I cut myself or scraped a knee or got upset, whenever anything was wrong, she’d shove one down my hole. Sugar first, bandage second.”

His expression was dreamy. “Mine carried butterscotch candies in her change purse.”

“With the change?”

“Yeah. Made my mother crazy, her sugaring me up that way. With ‘dirty candy,’ she’d say, as if Granny was giving me heroin.”

“I half-think that’s why mine did it, to irritate Mom.” I held out my hand so he could see the paw pads.

He put the cake in it and stepped into the pants. “Might take another box to fix that.”

“I think once I’ve eaten the last eight cakes—”

“You got six left.”

“Fine, six. I was hungry.”

“You were saying?”

“The rest of that box should take care of my psychic pain.”

He took the fishing pole from me, bracing it against the stump with an ease that spoke of practice, and said, “So you don’t need a kiss to make it better?”

I wrapped my arms around his waist, noticing that he almost felt like a man, noticing too how he didn’t quite, and not caring either way. We fit together, he and I, we were interlocked like jigsaw pieces and maybe I didn’t know why the picture we made was so complete, but I could roam now, in every direction but north, and there was no sense wrangling with why? anymore.

“Kisses make everything better,” I told him, but instead of offering up my mouth, I pressed my head to his chest and held on, listening to my caffeine-amped pulse thrumming in the pocket of air between his birch-bark skin and my ear, and knowing that that now I had what I needed to keep us both warm and dry.

“Wild Things” copyright © 2012 by A.M. Dellamonica

Art copyright © 2012 by Allen Williams