“There is no real perfection.”—Pete Ham

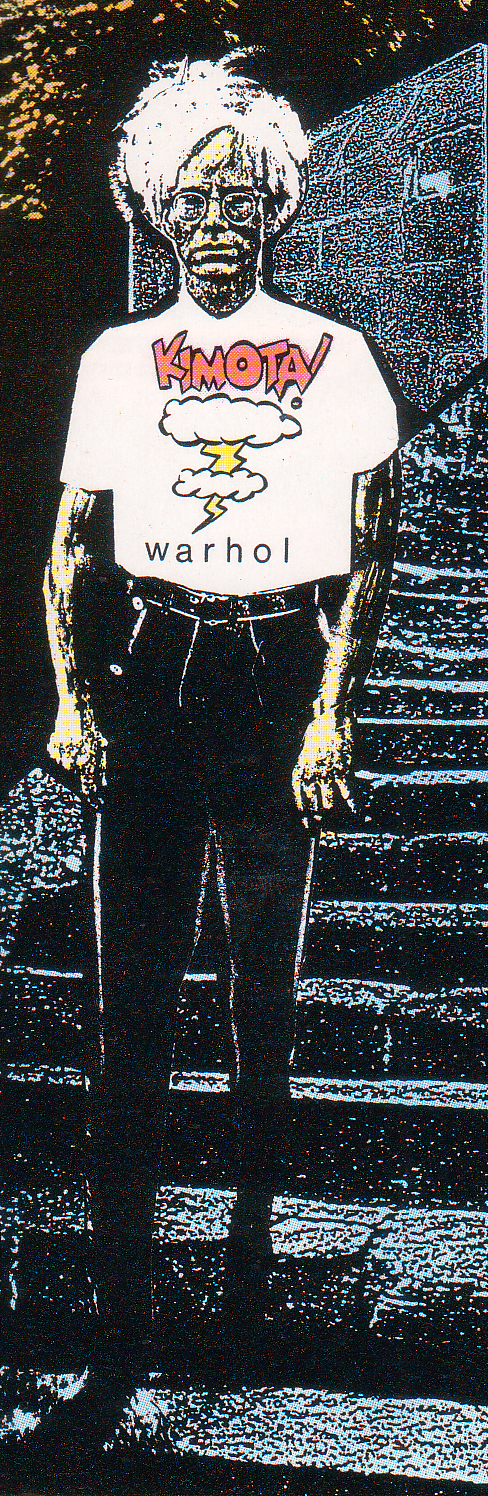

Neil Gaiman has stated that Alan Moore presented him with the notion of being his Miracleman successor in 1986. Moore recalled, “I think that I just handed it over to Neil. We might have had a few phone conversations, I don’t remember, but I think I knew he would have great ideas, ones that were completely fresh, ones that weren’t like mine. And indeed he did. He did the excellent Andy Warhol [story] (Miracleman #19), for example, which I think he took from a random line from one of my stories about there being a number of Warhols, but he expanded that into that incredible story. I can’t take any credit at all for Neil’s work, apart from having the good taste to choose him as a replacement, really.”

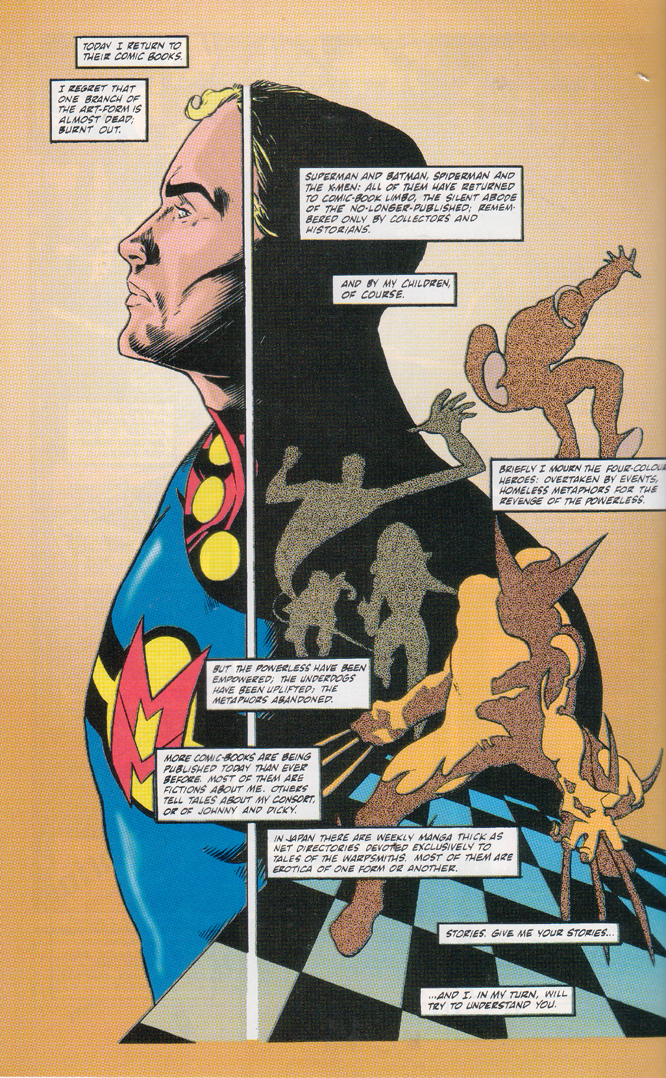

In spite of Gaiman and Buckingham’s first Miracleman being the short story/prelude “Screaming” in Total Eclipse #4, their “official” reign on the Miracleman series started with issue #17 (1990), the start of their “Golden Age” storyline—the new team also inherited Alan Moore’s one-third share of ownership in the character. “The Golden Age” (Miracleman issues #17 to #23) was an anthology of stories that explored the ramifications and effects of the citizens living within the utopia created by Moore and John Totleben. Each of these captivating issues featured a different protagonist, and each issue was beautifully executed and rendered in radically different art styles by Mark Buckingham, the first (and perhaps the most intense) of his many collaborations with Gaiman. The pair took a great chance by not putting Miracleman in the forefront of these issues, but each highly captivating tale has all the hallmarks of Gaiman and Buckingham’s finest work: beautiful and believable characterizations.

In spite of Gaiman and Buckingham’s first Miracleman being the short story/prelude “Screaming” in Total Eclipse #4, their “official” reign on the Miracleman series started with issue #17 (1990), the start of their “Golden Age” storyline—the new team also inherited Alan Moore’s one-third share of ownership in the character. “The Golden Age” (Miracleman issues #17 to #23) was an anthology of stories that explored the ramifications and effects of the citizens living within the utopia created by Moore and John Totleben. Each of these captivating issues featured a different protagonist, and each issue was beautifully executed and rendered in radically different art styles by Mark Buckingham, the first (and perhaps the most intense) of his many collaborations with Gaiman. The pair took a great chance by not putting Miracleman in the forefront of these issues, but each highly captivating tale has all the hallmarks of Gaiman and Buckingham’s finest work: beautiful and believable characterizations.

In regards to his approach on “The Golden Age,” Neil Gaiman commented, “I hadn’t even read it (“Olympus, Miracleman: Book Three”). But to me, immediately being told that you got a utopia and you can’t have any stories there… What I loved was the fact that you couldn’t do the stories that you read before—which was completely the delight of it. My own theory about utopia is that any utopia by definition is going to be fucked because it’s inhabited by people. You can change the world but you don’t change the nature of people. So immediately the idea for the very first story was the idea of people just going to pray. It’s like, okay, well, we’ve got God coming here. God is on Earth, he’s living on a giant pyramid on the top of somewhere taller than anything you can imagine—so let’s go and let’s pray. I loved the idea of someone getting all the way to top. And if you pray to God and he’s there, sometimes he’ll say no. That really was just the thrust of the very first’s premise.”

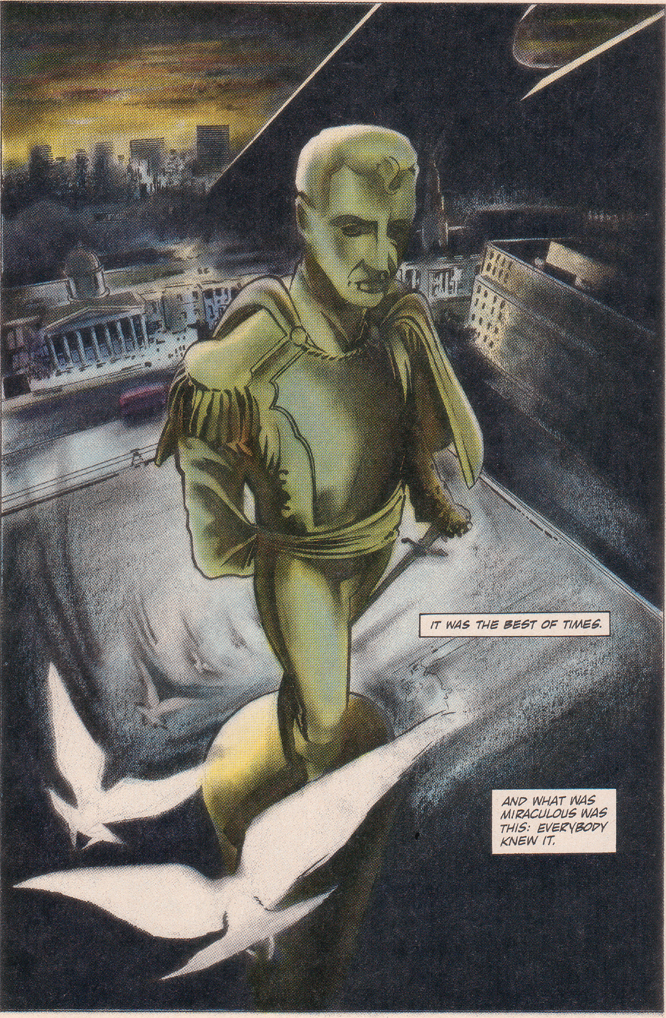

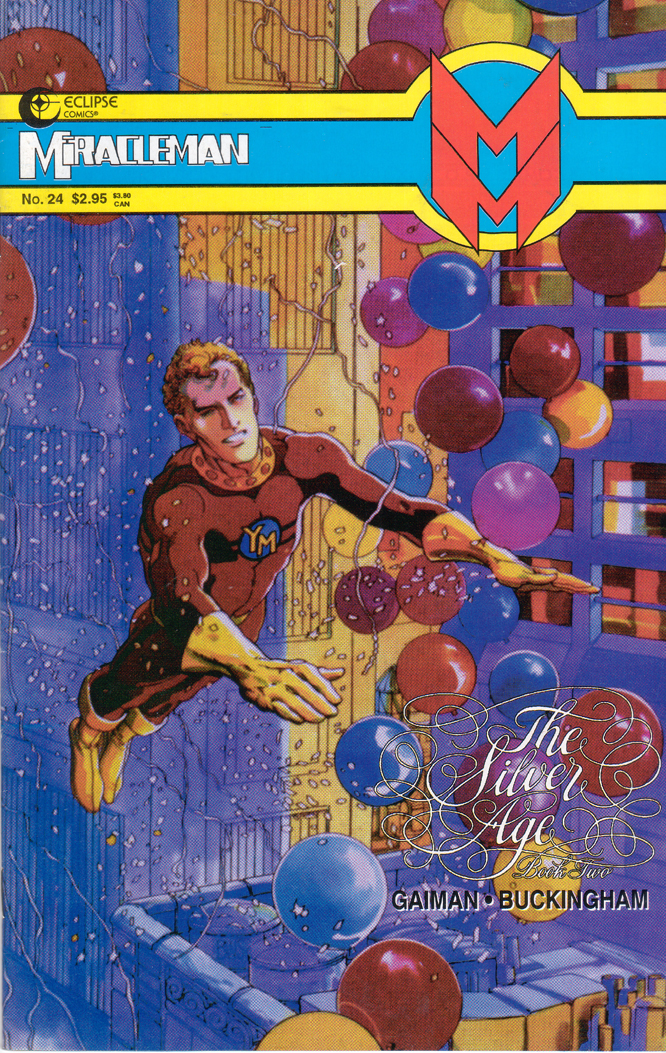

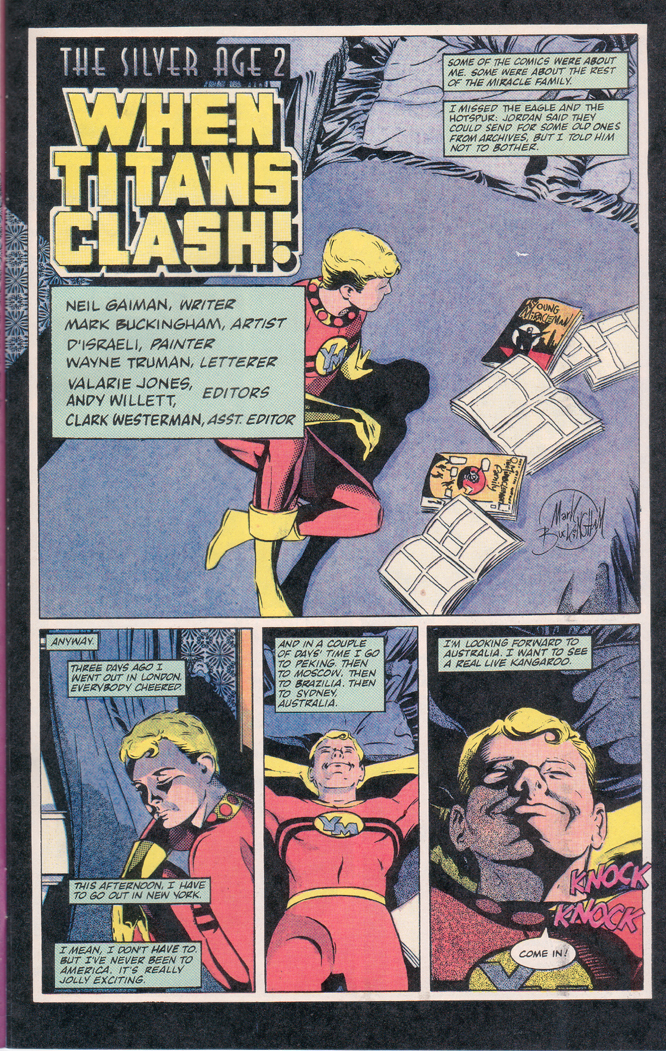

The follow-up books to “Golden Age” were to be “The Silver Age” and “The Dark Age.” “The Silver Age” would have dealt with the self-discovery and journey of the resurrected Young Miracleman. Only two issues (#23 and #24) were released, and a completely drawn and lettered issue #25 remains unpublished since the final days of Eclipse Comics. Gaiman and Buckingham’s final arc, “The Dark Age,” was a storyline set further into the future that would have seen the villainy of the ever-popular Johnny Bates return for the end of all days.

Unfortunately, these plans went unrealized as Eclipse Comics, financially struggling, closed its publishing door in 1993 (and ultimately filed for bankruptcy in 1995). The financial difficulties of the company had already hampered the release and creative production of the series in 1992 and 1993, since only a single Miracleman comic was released in each year.

Before Eclipse’s demise, the 1990s appeared to be a period of big expansion for Miracleman with the release of the Miracleman: Apocrypha mini-series and an impending brand new series named Miracleman Triumphant. A recent revelation to me was the fact that Eclipse had begun to work with Mick Anglo on straightening the Miracleman/Marvelman rights, once and for all, because Hollywood was expressing interest in Miracleman’s film rights.

In the upcoming new edition of Kimota!, Dean Mullaney discloses, “After Eclipse acquired the trademark ownership from Dez (Skinn), Garry Leach, and Alan Davis (Alan Moore retained his 30%), we starting pitching the character for movies and were getting lots of interest. The production companies, understandably, wanted clear title before they would do a deal. So, my brother Jan started negotiating with Mick Anglo’s attorneys. We had a handshake agreement, by which Anglo would license to Eclipse his ownership, and we, in turn, would pay him an advance against a percentage. But then the shit hit the fan when the Rupert Murdoch-run HarperCollins put Eclipse out of business (but that’s a whole different story). The upshot is that the deal was never signed. Where that leaves it now is up to everyone’s attorneys.”

On February 29th (leap year, no less) of 1996, Todd McFarlane purchased all of the creative properties and agreements held by Eclipse Comics in New York bankruptcy court for a mere $25,000. His admiration for Dean Mullaney and the possibility of mining Eclipse’s catalog of characters led to his purchase decision. Amongst those properties, McFarlane would technically assume the 2/3 ownership of the Miracleman character. In the years since the purchase, McFarlane and his company have done very little, comic book-wise, with the Eclipse properties. However, he did introduce Mike Moran in the pages of Hellspawn for a few issues, and would release his artistic interpretation of Miracleman as a statue, an action figure, and a limited edition print (with artist Ashley Wood). More recently, a redesigned and rebooted version (with the familiar MM logo) of the character as been renamed now as Man of Miracles; he’s appeared in Spawn #150 and Image Comics: Tenth Anniversary Hardcover, and, even, as an action figure of his very own.

Throughout the late nineties, Neil Gaiman tried to resolve his differences with Todd McFarlane over royalties that he felt entitled to for characters (Angela, Medieval Spawn and Cogliostro) that he co-created (with and for McFarlane). A 1997 attempt to trade the writer’s co-ownership in these Spawn-related characters for the infamous Eclipse two-thirds share of Miracleman never materialized.

At a 2001 press conference for Marvel Comics, a fund called Marvel and Miracles, LLC was announced—the fund would use all profits from Gaiman’s Marvel projects to legally procure the Marvelman rights from McFarlane. Ultimately, the Gaiman and McFarlane’s legal showdown took place in the verdict held on October, 3rd of 2002, a court proceeding in a United States District Court. The English writer won $45,000 from Image Comics (for the unauthorized use of his image and biography in Angela’s Hunt) in damages, $33,000 in attorney fees for the Angela’s Hunt portion of the case, his share of the copyright of his co-creations for McFarlane and, lastly, an accounting of the profits due to him for those three characters—the Miracleman rights were not resolved in this courtroom.

The legal case was always about creator rights, which is why Gaiman’s attorneys optioned for a decision on the monies owed as opposed to enforcing the botched 1997 trade for the uncertain Miracleman rights. During the trial, Gaiman’s attorneys were able to see all the old Eclipse documentation for Miracleman, and afterwards felt extremely confident that they had found ways to begin publishing Miracleman comics. Their only product, thus far, has been Randy Bowman’s 2005 Miracleman statue, a limited item of only 1,000 copies.

Sometime in 2005 and 2006, the name of Mick Anglo (now a nonagenarian) began to make waves. It was rumored that he was seeking to re-establish his Marvelman copyright in the British courts. In actuality a new player, a Scottish man named Jon Campbell and his Emotiv company, were doing their dandiest to establish Mick Anglo’s copyright on Marvelman under English copyright law. Within 2008’s Prince of Stories: The Many Worlds of Neil Gaiman book, Gaiman stated, “I know they (Emotiv) bought the rights from Mick Anglo for four thousand pounds and have been working hard to establish his ownership of the property…” By buying the rights, they could do all the legwork in the English court system for the elderly Anglo. Since work-for-hire doesn’t exist in the U.K., it is possible for someone to commission work and take an assignment of rights many years later. It’s likely that this was the scenario which led to Anglo and Emotiv successfully proving their case—but very little information has been disclosed publicly about all the real drama behind this. By technically establishing Anglo’s copyright, the scenario would make any prior claim to the complex ownership of the character null…. at least in theory.

With the Anglo copyright to Marvelman in their hands, Emotiv looked at various scenarios to bring back the character before engaging in conversations with Marvel Comics in 2009, after Gaiman’s attorney put both parties together. After substantial due diligence, Marvel negotiated the rights from Emotiv and announced their ownership of the vintage Marvelman—the stories and art from Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman stories are owned by the writers and artists of these stories, and were not a part of Marvel’s purchase.

A year later, Marvel has just begun to reprint those old Marvelman strips from the Len Miller days. Although there isn’t a huge public outcry for these vintage stories, Marvel is doing their part to stake their claim on the character and enforce the copyright of their acquisition. The “House of Ideas” has made no solid announcement about the day when they’ll actually print the real deal—the books penned by Moore and Gaiman. The negotiation to bring the good stuff back to print continues to this day. Weep not, my friends, there’s always hope that Marvel will get the classic Miracleman stories done right; in a way that will hopefully treat the great artists of the classic material with a touch of class. Once in print, these stories will no doubt be a perennial seller, whether as books or films.

For the last creative team of Miracleman, there would be nothing more satisfying than wrapping up the stories that they spoke about when their careers were just in their infancies, more than twenty years ago. In 2000, Mark Buckingham said, “It remains the project I would drop everything to return to. Just because it’s the most obviously me of anything I’ve done. So many other projects I’ve worked on or things I’ve done have shown influences of other people or have been me tailoring material to fit what’s gone before or what I’m feeling the audience wants from me. Certainly with Miracleman it was very much my personality and Neil’s personality coming to the full and telling a story that we wanted to tell in a way we wanted to tell it. I don’t think I’ve ever had as much freedom creatively on anything else and would relish the chance to be pure again. [laughs]”

There you have it: the gist to most of the drama surrounding my favorite superhero character, on the page and behind-the-scenes. Hard to believe that when I started writing and interviewing for what eventually became Kimota!: The Miracleman Companion, back in 1998, all I wanted was for people to never forget the great stories penned by Moore and Gaiman, to always remember the awesomeness and beauty of the unforgettable artwork rendered by John Totleben, Garry Leach and Mark Buckingham. After the demise of Eclipse, it truly felt that the character of Miracleman and his classic works would be forever trapped in a black hole of litigation, destined to be lost as a silly urban legend of comics. Some day, hopefully very soon, all of you will be able to experience a legitimate presentation of this entire saga, in its entire splendor. Yeah, I’ve never stopped believing in miracles.

Kimota!

Read Part One. Part Two. Part Three.

George Khoury is the author of the upcoming brand-new edition of Kimota! The Miracleman Companion, The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore and more.