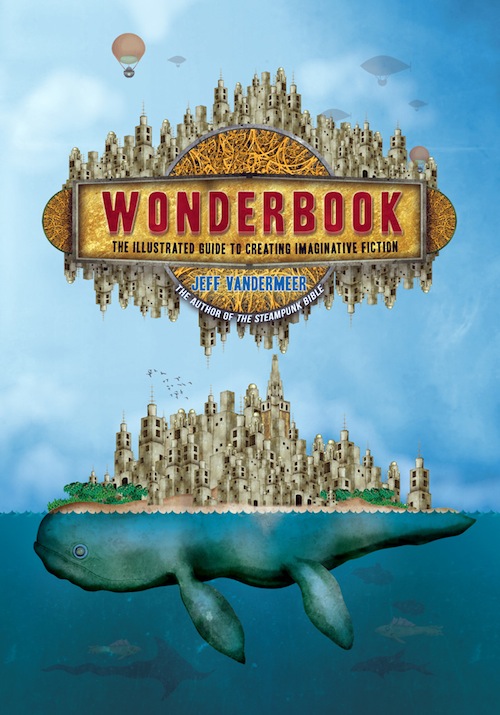

Check out Wonderbook by Jeff VanderMeer, available October 15th from Abrams Image!

This all-new definitive guide to writing imaginative fiction takes a completely novel approach and fully exploits the visual nature of fantasy through original drawings, maps, renderings, and exercises to create a spectacularly beautiful and inspiring object. Employing an accessible, example-rich approach, Wonderbook energizes and motivates while also providing practical, nuts-and-bolts information needed to improve as a writer.

Aimed at aspiring and intermediate-level writers, Wonderbook includes helpful sidebars and essays from some of the biggest names in fantasy today, such as George R. R. Martin, Lev Grossman, Neil Gaiman, Michael Moorcock, Catherynne M. Valente, and Karen Joy Fowler, to name a few.

What Not to Dramatize

One advantage to cutting scenes before or at the point of a confrontation or other significant encounter is that not every such event needs to be dramatized in your story or novel. Sometimes this has everything to do with the point of view of the novelist. China Miéville’s decision in The Scar, about pirates and a floating city of boats, to cut away before the character’s ultimate encounter with a leviathan expressed the author’s explicit intent not to cater to the usual expectations about how certain types of fantasy novels end. But other reasons apply—for example, you may not have the skills to convey a particular type of encounter and yet need that event to occur during the time line of the novel. There’s no shame in this. If you have no interest in or proclivity for writing battle scenes, you shouldn’t necessarily have to write one.

Beyond the eccentricities and skill set of the writer, the decision about what to dramatize concerns emphasis and how “bringing it to life” will either support or destabilize your story. Action scenes with no emotional stakes involved are fairly pointless to commit to the page. A noisy, prolonged fart may be a battle cry in a comedy of errors pitting class against class or just an embarrassing mistake on the part of the writer. Meals may or may not have any more significance or importance when dramatized than if summarized. In Babbett’s Feast by Isak Dinesen, food is a means of communication and fosters a sense of community central to the core of the novel. Not showing sumptuous banquets would be a mistake. But the same meals pushed into Miéville’s The Scar would be just as much of a mistake; sometimes a pirate’s sandwich is just a sandwich.

Similarly, it’s instructional how Daphne Du Maurier handled the sexual relationship between husband and wife in her famous 1950s novella “Don’t Look Now” compared to director Nicolas Roeg’s approach in the movie version. Because Du Maurier could use words to convey the couple’s relationship and Roeg only had images, Roeg’s version is forced to be much more explicit in attempting to show the intimacy and love between the two. How would explicit sex have changed the balance of elements and the role of scenes in the novella version?

Some writers almost always take a “less is more” approach to certain subjects. Stephen Graham Jones, known for horror and noir, is a writer who usually lets the sex happen off page. “Not because it is automatically weak writing or undeserving of page time. It’s mostly that I’ve always suspected that people write those pages long sex scenes for the same reason other writers wax on about unicorns: because, man, they’d sure like to see a unicorn someday.”

Wonderbook: The Illustrative Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction © Jeff VenderMeer, 2013