I’ve never liked my brother-in-law much, and now he’s caught the zombie infection. Do I have to invite him to our family Thanksgiving celebration? I’m worried he might eat someone’s brains instead of the turkey.

He may be undead, but he’s still your brother-in-law. Blood is thicker than water, and in this case thicker than brains, too. You should be respectful of his dietary preferences, just as you would provide an alternative for vegetarians or those with food allergies. If he skips over the cranberry sauce, stuffing, and deviled eggs and goes straight for the blood pudding, it’s not your place to criticize, especially if you want to stay on your sibling’s Christmas list this year.

Don’t expect much in the way of intelligent conversation, either. Consider seating him across from your aunt who nods off in the middle of every meal, or maybe at the kids’ table; somewhere where his mumbling and moaning won’t be noticed or remarked upon.

However, it is not only appropriate but responsible to set down some guidelines beforehand and recruit your sister or brother to help enforce them. “No snacking on other guests” would seem like an obvious choice.

I’m my grandfather’s favorite grandchild, and he decided long ago to leave me his house in his will. Well, he hasn’t died, but about five years ago he undied. My cousins are living in the house now and making a mess of it while my grandfather shambles from room to room. Do I have any legal recourse?

No one’s quick to acknowledge a zombie apocalypse, and lawyers and lawmakers might even be slower than everyone else. Is “undead” more like “dead” or more like “living”? Zombies can breathe, move, and eat on their own; they can’t sign contracts, write checks, or, well, speak much. It’s smart to cover the zombie contingency in your living will, but if your grandfather neglected to do that, your options are limited at present.

Limited, but not nonexistent. Speaking of lawyers, no one’s yet been successfully prosecuted for zombie murder, and as long as you can muster a reasonable self-defense argument, that’s not likely to change anytime soon. The grandfather you knew and loved is gone; a shotgun blast to the head and no one will be wondering whether Gramps still owns the deed to that house.

Rrrrr! Aaaaaaaa! Uhhnnnng? (According to my Zombie-English Dictionary, this means something to the effect of: Ever since I was turned, the precision of my speech leaves something to be desired. Can speech therapy help me regain my former verbal coherence? Or am I doomed to be forever a monosyllabic monster?)

To answer this question, I consulted Mac Montandon, zombie expert and author of The Proper Care and Feeding of Zombies. What exactly is it that inhibits zombies’ rhetorical skills? According to Mac, “[t]he main reason zombies can’t speak properly is because the frontal lobe of their brains is not very active.” The frontal lobe is where we do our abstract thinking and problem solving, and “as everyone knows, it’s difficult to speak properly if you can’t think abstractly and problem solve!” That’s not even counting the problem of decomposition, which begins very soon after death. As Mac points out, “If you think it’s tough trying to speak properly with an inactive frontal lobe, just try it once the skin of your face has sloughed off. Not easy!”

The rehabilitation route, then, is not likely to do you much good, so what else can you try? Depending on your current level of decomposition, carefully enunciating each word will increase your ability to be understood. On the other hand, taking the time to speak carefully might mean that all the humans in the vicinity run away before you finish a sentence. The best solution may be simply to be concise. Rather than “I want to eat your brains,” you will be more quickly comprehended with “Braaains” alone.

Now some unsolicited advice: when the zombie apocalypse occurs, please refrain from chomping on my brains. After all, you don’t know where they’ve been.

Whining about werewolves? Ptrouble with pterodactyls? Agonizing over aliens? Leave your questions in the comments and they may be answered in a future column!

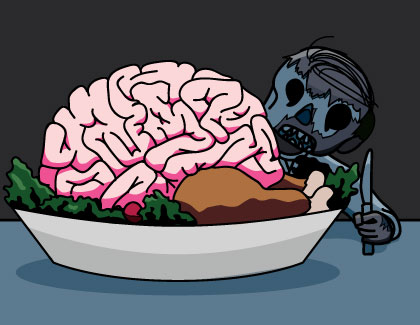

Art by Kim Nguyen

Ellen B. Wright lives in New York, where she works in publishing and takes an excessive number of pictures. She thinks we ought to start looking into preserving Miss Manners’s head, brains, and/or genes, whichever seems most scientifically feasible, because we’re really going to need her in the future.

Kim Nguyen is a DC-based graphic designer fresh out of university. In her free time, she rock climbs and shoots zombies.

How do you handle overly helpful brownies? There are a couple at home that keep doing too much. They mended my torn jeans that I paid $100 for. I was planning on cooking with my boyfriend as a date, but they had made everything when we arrived. I can’t catch them to speak face to face, and my verbal pleas and notes aren’t doing much. I don’t want them to leave, just to practice a bit of restraint.

I really deeply dislike zombies (not that I like vampires either) let’s stick with the generic undead just to cover all our bases. I loathe the undead. Lately I’m seeing them around more and more. Should I or should I not employ nuclear weaponry to destroy every last one?

Hilarious!

Now what do I get my zombie bride for an anniversary present? :P