The title of this post is my considered response to Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End. It was my response when I first read it at twelve, and it’s still my response reading it today.

Childhood’s End was published in 1953. It’s a truly classic science fiction novel, and a deeply influential one, and one of the books that makes Clarke’s reputation. It’s also a very very strange book. It does as much as any half dozen normal books, and all in 218 pages, and it does it by setting up expectations and completely overturning them, repeatedly.

The prologue of Childhood’s End is brilliant, and it stands completely alone. It’s 1975. There’s an ex-Nazi rocket scientist in the U.S. worrying that his old friend the ex-Nazi rocket scientist in the U.S.S.R. will reach the moon before him. You’ve read this story a million times, you know where it’s going, you settle in to a smooth familiar kind of ride. Then quietly without any fuss, huge alien ships appear over all of Earth’s major cities. And this is just the first surprise, the first few pages of a book that goes about as far from the standard assumptions and standard future of SF as it’s possible to go.

People talk about SF today being too gloomy—my goodness, Childhood’s End has all of humanity die and then the Earth destroyed. It’s not even relentlessly upbeat about it, it has a elegaic tone.

You’ve got to like having the rug pulled out from under you to enjoy this book, and when I was twelve I wasn’t at all sure about it. People talk about SF written now that can only be read by people familiar with how SF works. If there ever was a book that epitomises that it’s Childhood’s End. It’s a roller coaster ride that relies on you lulling you into thinking you know what it’s doing and then shocking you out of that. It’s a very post-modern book in some ways, very meta, especially for something written in 1953. And for it to work properly, you have to know SF, SF expectations, the kinds of things SF normally does, so that you can settle down enough to be going along smoothly and then get the “Wow” when you hit the next big drop.

When I was twelve I liked it much less than I liked the set of “everything else that had been written by Clarke before 1976,” and it was precisely because of this rug-jerking. When I was fifteen or sixteen I had a category in my head that contained Nabokov’s Pale Fire and John Fowles’ The Magus and Childhood’s End, and that category was “good books where you can’t rely on things.” Now I recognise Nabokov and Fowles were writing unreliable narrators, and Clarke, well, Clarke was doing this really interesting experimental thing. It’s a plot equivalent of an unreliable narrator.

Now, of course, these successive “wow” hits are the thing that I admire about the book the most. You think you’re getting a rocket-ship story? Surprise, alien invasion! You think you’re getting an alien domination story with intrigue and the unification of Earth? Surprise, you have a mystery about the appearance of the aliens with a truly cool answer. (And that cool answer is going to be overturned again at the end.) You think you have a utopia with mysterious aliens, with the big question being about what the all-powerful aliens are really up to? Actually no, this is a story about humanity’s children developing psychic powers and disappearing, almost a horror story. Except that there was this one guy who stowed away on an alien ship and he comes back when there are no more humans and witnesses what happens at the very end, and it turns out that the all-powerful aliens you’ve been wondering about have a lot of things they’re wondering about themselves.

Wow.

There are some odd things about the future that Clarke got right and wrong. No aliens yet! But it’s impressive that he predicts a reliable oral contraceptive leading an era of sexual liberation and equality, even if he couldn’t quite imagine what gender equality would look like. (It’s odd how very much everyone tended to miss that “equal work for equal pay” meant that women wouldn’t be dependant anymore.) Anyway, from 1953 that was impressive predicting. I’m pretty sure that this is the first time I’ve re-read Childhood’s End since Clarke’s homosexuality became public knowledge, because I noticed the line about “what used to be vice was now just eccentricity” and felt sad for him personally—1953, when homosexuality wouldn’t be legal in Britain until 1969. He was off on that prediction, it’s not even eccentricity. Well, he lived to see same-sex marriage become legal in Canada and be discussed in Britain and the U.S.. There are no visibly gay people in this book. There are straight people with multiple partners, however, as an accepted social institution in a utopia that includes term marriages.

One interesting thing about this future is that there’s no space travel. The aliens have space travel, and they kindly allow some humans to have rides to the moon. But they say that “the stars are not for man.” Another is that humanity seems to be entirely outclassed by the overlords. In fact this isn’t quite the case, as humanity has the potential to become part of the inhuman superhuman psychic overmind, but for the bulk of the book this is the absolute opposite of human supremacist. Earth is colonized by the aliens—and the specific analogy of Britain colonizing India is made more than once. The aliens impose peace through superior technology and for their own inexplicable reasons, which humanity can only hope are for their own good.

Whether it is for our own good, and whether it is a happy ending or a horrific ending, is a matter where reasonable people can disagree. (What I mean by that is that my husband thinks it’s a happy ending and has since he was twelve, and all that same time I’ve been horrified by it.) I think Clarke intended it as positive but also saw the horror in it. I also think he did post-humanity and what it means to see a wider universe much better here than in 2001. There’s a marvellous poetic sequence where a child who is transforming into inhumanity has dreams of other worlds while his parents and the overlords watch and wonder.

Characters are never really Clarke’s strong points, and they’re not here. He’s great on ideas and poetic imagery around science, but his characters are usually everyman. The best character in Childhood’s End is George, who sees his own children becoming something more alien than aliens and doesn’t like it, and even George is more a line drawing than a solid character. If you want something with good characters and where women are more than scenery and support systems, read something else.

The real character here is humanity. And the odd thing about humanity as a character is what happens to it. If you have to force it into one of my “three classic plots” it’s “man vs plan,” and plan completely wins. If you want to use someone else’s “three classic plots” it’s boy meets girl, with humanity as the girl and the overlords as the boy—but it’s not much of a romance. Humanity considered as a hero here is completely passive, everything that happens, happens to it, not because of any action or agency of humanity’s. But that’s one of the things that makes the book good and unusual and worth reading. Wow. Did I say “wow” already?

Science fiction is a very broad genre, with lots of room for lots of kinds of stories, stories that go all over the place and do all kinds of things. One of the reasons for that is that early on there got to be a lot of wiggle room. Childhood’s End was one of those things that expanded the genre early and helped make it more open-ended and open to possibility. Clarke was an engineer and he was a solidly scientific writer, but he wasn’t a Campbellian writer. He brought his different experiences to his work, and the field is better for it.

Childhood’s End has been influential, but there isn’t much like it. People write alien invasions and use Clarke’s imagery (when I saw the trailer for Independence Day I was sure they’d made a film of Childhood’s End), but they keep on writing about alien invaders that humanity can fight off, not alien colonizers with their own agendas. And the only thing I can think of that’s really influenced by the end is Robert Charles Wilson’s ultra-creepy The Harvest.

I assume everyone has read it already, but it’s worth reading again now you’re older and thinking about what Clarke was doing.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently the Nebula winning and Hugo nominated Among Others. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

Jo – sometimes you hit the nail on the head and you did so here. The book floored me when I read it almost 40 years ago and it still does. Unlike with many classic books, I retain a pretty darned clear memory of the plot.

Childhood’s End is, as far as I’m concerned, the finest science-fiction novel written. It does in 200 or so pages what thousands of pages of more recent spew fail to do: elicit a deep sense of awe and wonder and humility at Man’s place in the Universe. The only other novel that came close to having the same effect on me was The City and the Stars — also by Clarke.

Other authors, such as Niven and Heinlein, may do the big technology and cutting-edge science better, perhaps, but Clarke does the poetry of wonder, in much the same way as Bradbury.

It’s a shame it’s not yet been made into a film, but there are so few writers and directors I would trust with this material, especially now that Clarke is dead. Certainly it would have to be at least a semi-independent production without Hollywood interference. (And I would love to see the spittle-flecked reaction from the Christian Right to the Overlords.)

I note from the Wikipedia entry that the current rights to Childhood’s End are held by Universal Pictures, and that the director currently ‘assigned’ to the project is one Kimberly Peirce, whose other current projects include two crime dramas, a sex comedy, and a remake of Carrie. One is not filled with confidence.

as humanity has the potential to become part of the inhuman superhuman psychic overmind

Just as the contents of my oven, simmering even as I type, have the potential to become part of me. How sad it is for the Overlords that they are forever barred from becoming a psychic slurpee.

(Is this how working dogs see sheep?)

An absolutely incredible book.

I read it when I was 16 and I can remember exactly where I was when I finished it. I was in a car driving into Los Angeles while looking at universities and I finished the book, sat dumbfounded for about a minute, and then looked out onto a valley floor that outshone the night sky above.

It was the first time I ever finished a book and then immediately wanted to write criticism of it. Not an Amazon review, but serious literary criticism. It was about reverse dramatic irony, the Overlords and the book’s commentary on individualism.

I have always found the ending horrifying on a number of levels, but the book wouldn’t be complete without it.

NomadUK @3 – To be fair, Peirce also directed Boys Don’t Cry, which is great, and Stop Loss, which got good reviews. Taking Judd Apatow comedies for money is just a thing that happens to directors if they want to keep working.

That said, she seems like a mismatch to adapt anything by Clarke whatsoever. She’s focused entirely on character in small-scale realist settings.

James: That sheepdogs want to become Sunday dinner and mourn that they never will? That’s a compelling image.

GBrell: What do you mean, reverse dramatic irony? You should write that right here whatever length you care to. (And picturing that scene in the car, I want to ask whether your copy of Childhood’s End is inscribed “Beware of Folly”!)

Jo, regarding your penultimate sentence, did you ever do a post on RCW’s The Harvest? That was the first book of his I read, and I was immediately enchanted. I still believe he’s never topped it.

P-L: No, I haven’t done a post on it, but I will at some point. My favourite book of his is definitely Spin.

Assuming we define dramatic irony as a statement or actions by a character that is better understood by the reader than the other characters (i.e. half of Oedipus Rex), I am using the term to mean actions or statements by characters that the author intends to mislead the reader so that they understand less.

It’s essentially the point you make in the OP that the book is constantly reversing our expectations (which is even more incredible considering that most of the tropes its subverting were barely established), but it’s also wonderful because it’s not just a plot device. It’s the very structure of the novel that puts the reader in the same position as humanity in the novel. Even with the panoply of viewpoints, we the readers know as little (and because of our expectations, even less) as the doomed humanity of the book.

Reverse dramatic irony.

This post makes me want to re-read Childhood’s End. Maybe I’ll write that essay after all.

PS: I just ordered Harvest because it sounds incredible.

Jo: Among things influenced by the final sequence of Childhood’s End I’d include Blood Music, even though Greg Bear’s version feels a little more conservative or comforting than Clarke’s (I mean, humanity has sort of melted down and then vanished to some other plane of reality, but you still end up with a bunch of intact human personalities hanging out with each other inside a shared dream).

Rick Veitch’s extremely strange graphic novel The One goes in a similar direction, eventually.

I must be the only person who doesn’t like this book. I read it for the first time only 6 years ago, in my late 20s, and thought it had aged terribly and was pretty thin on plot. (I read Asimov’s original Foundation trilogy around the same time and had a similar reaction.) Thing is, I love some of Clarke’s (and Asimov’s) and other books. I dunno.

Weirdly, for a recent release, Clarke rewrote the prologue so that it takes place after 2000, as a moonbase prepares for a Mars mission – but the rest of the novel still begins in the 20th century with characters who were adults during WWII and are still only in middle age.

I also read this book as a young teenager, and you can count me among those who were horrified by the ending. I had no urge to surrender my humanity, and the thought of watching my children surrender theirs was absolutely chilling.

At that age, I much preferred the Campbellian stories of Analog, where the humans were always more clever than the aliens, even when it was them visiting us. Tales like ‘Sleeping Planet’ by William Burkett, where a handful of plucky humans foil an alien invasion that puts most of humanity into a coma.

And, while I am more self aware than I was as a teenager, I still prefer human characters, who exhibit human virtues, which is why all these predictions of a ‘singularity,’ where humanity transforms itself, fill me with that same feeling of dread I felt when I put down Childhood’s End.

I’ve always loved the ending basically because I’ve never really had much time for the notion that humanity is the only way of being worth having, or necessarily the best; SF stories that assert otherwise always strike me as having fundamentally limited imaginations of the possible.

In a recent podcast on his official fan site, Dwight Schultz said that the one book he’d most like to make into a movie would be Childhood’s End.

Jo,

This is one book that I loved at 14 and re-read recently in fear and trembling but loved just as much again. I’ll admit that Clarke is not my favorite writer (mostly because of those non-characters you mentioned) but this is still one of the genre’s best.

Perhaps it is a kind of Buddhist end-times story.

Humanity in the story is not passive, any more than a child growing up is passive. But the active thing is life first and the individual (or collectivity) second.

I have often heard people claiming the whole thing is meant to be a deception – an Overlord plot to destroy humanity. One reviewer even claimed the Overlords are supposed to be actual devils (highly unlikely considering Clarke’s worldview). Thing is, it certainly can be read this way, even if I rather doubt it was author’s intent.

It’s a story that made me go “Wow!!!” as well.

But I’d already made my acquaintance with Arthur C. Clarke’s quirkyness prior to reading Childhood’s End, and I’d already made my acquaintance with one of the books that inspired it, Last Man and First Man – and Nebula Maker and Star Maker – courtesy of his own praise of it in the foreword to the Corgi publication of The Lion of Comarre and Against the Fall of Night. So while it took me by surprise, it didn’t phase me any.

It’s probably one of the greatest of the twentieth century’s philosophical novels, an ideas novel written by someone who vehemently disagreed with the stated premise of the plot. And like Stanislaw Lem’s His Master’s Voice and Solaris, completely beyond the comprehension of most philosophers …

The Grey Drape@20: written by someone who vehemently disagreed with the stated premise of the plot

Yes, exactly! I remember reading the copyright page and noting with great surprise the statement ‘The views expressed in this work are not necessarily those of the author’, or words to that effect. I have never seen anything like that in a novel, before or since.

I read this first some 45 years ago and I didn’t really like it. I have never been one who wants to see the human race ended. I tried it again some years ago, and my perspective had not really changed.

I am pretty sure Childhood’s End opened my eyes to the plot potential of the twin paradox, which means I have to have read it before A Time for the Stars or The Long Road Home. That means I encountered the Clarke some time between 1970 (when I first encountered Heinlein in the form of my older brother recounting Orphans of the Sky from memory) and 1973, by which point I’d discovered Kitchener Public Library’s trove of RAH YAs (Anderson I didn’t encounter until 1976 or 1977, I think).

James: I also read Clarke before I read Heinlein, because hey, alphabetical order.

Thinking about it, while my father did not read SF he was interested in rocketry [1] and so while he didn’t have stuff like Childhood’s End or 2001, he did have

The Exploration of Space in an edition whose binding was crumbling by the time I got to it. I bet that’s how I found Clarke.

1: In another trouser leg of time his interest in nuclear power [2] + rockets landed him at Jackass Flats.

2: I have been informed pretty much every reactor in North America uses work he and a grad developed.

I think the first science fiction story I ever read was a short story about the crew of a space station with a self-destruct mechanism that had to be reset or something every day, and some trained monkey got loose and was messing with the controls as they watched in horror … something like that.

But — after that, the first real science fiction I can remember reading was Clarke. Probably Childhood’s End, maybe Against the Fall of Night (which later became The City and the Stars). In any case, I consider myself fortunate, as going through Clarke’s works, and then Asimov’s, kept me clear of Heinlein for a long time and thus delayed my exposure to libertarianism until I was old enough to recognise it as shite, and I was able to enjoy the stories and ignore the politics.

The review made me want to read the book again as it was probably around the 1976ish timeframe that I read it last and that was from a library. So, I don’t have a physical copy.

Ah ha! I thought, I’ll just get a digital version. It turns out there isn’t one (that I could find) and it looks like few of Clarke’s books have digital formats available.

From what I recall, I wasn’t entirely happy with the subliming into a group mind resolution. Surprising, but not happy.

I think I have to blame the Freemans’ You Will Go to the Moon for biting me with what turned into the SF bug. I know I looked at it over and over before I manifested verbal skills so by the time I was four (I deigned to speak comparatively late in life, which caused some concern. Afterwards they missed the silence). I remember being in a car headed down Fairway Road looking at transmission towers and imagining they were the skeletons of abandoned spacecraft. Going by what had not been built out there yet, that was no later than 1967, so by the time I was six I’d been hooked.

Wait, no: we were in the bungalow about 20 feet above the current surface of the field next to Columbia Lake [1] so that was 1966 and I was no more than five. Good work, Freeman and Freeman.

Same time frame I was exposed to this:

http://youtu.be/32ZsjRUdw8E

1: The hill the house was on was torn down but the bungalow itself was preserved. I think it got moved to one of the dunky villages near KW.

This book shows up again and again when I talk with other GLBT folks about science fiction that influenced us a lot as young people. Most of us read it first before coming out or even necessarily really self-identifying, and there was ungrasped power in the idea that there can be great, tremendous good things you can’t have without giving up the good you have right now.

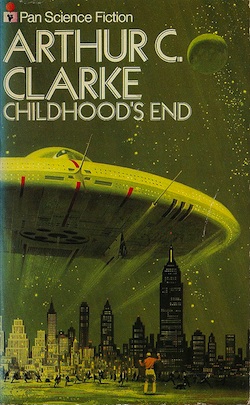

I read Childhood’s End somewhere around age 12 (i.e., The Golden Age of SF, as Peter Graham once termed it), obtaining my copy from the Scholastic Book Service, with the same cover illustration as posted above. With that image, no way was I going to miss reading this book!

I was greatly impressed with it. Saddened but not horrified, since it spoke to the evolutionary existential dilemma, the succession of species (albeit twined with the Idea of Progress, to sweeten the bitterness, though now discredited). After all, the book is called CHILDHOOD’S End. Who does not want children to grow up? Which usually entails the death of the parent (pace, Oedipus, Freud, and Prometheus). Of course, being 12, I was probably hoping for some of those uber-mind genes experssing themselves in me, too.

If anything, I felt most sorry for the Overlords, sterile servants that they were.

The parallel I draw now is with Evangelion. I’m surprised I’m the first to post this here, but the ending (indeed, objective) of NG:E was surely inspired or influenced by Clarke, and may have been a (then) subconscious influence on my dislike of that story. I did NOT like what happens to humanity in Childhood’s End and thought it could be a very extreme extrapolation of Communist ideals of equality, from each/ to each, and such.

Evangelion still confuses me on the fight over how to turn us all into yellow glop. If the front seaters are intent on driving us over a cliff, what does it matter who is at the wheel?

Count me among the fans. From early teens (in the 60’s) this was part of my triumvirate of favorite books (along with Foundation and The Moon is a Harsh Mistress) in terms of lasting emotional impact. Regardless of how you interpret the ending, it gets you in the gut and stays with you. And the peak (which comes back to me again and again along with the Mule’s final line about how he got his name) is the Chief Overlord: “Yes, we are midwives. But we ourselves are sterile”

Wow.

I read this when I was very young, because it was on a list of SF classics, which I was working my way through.

I read it so young that I had no knowledge whatsoever of any of the conventions it is working against or any of the plot expectations it assumes you to have. As a result, I was extremely confused by its reputation– this is a book where if you don’t have the background you literally cannot see why it is good.

I know now, but I’m unable to enjoy it, because everything in it is coded for me as innately unsurprising, as just the way one would expect this sort of story to be. Business as usual. I’m also pretty much incapable of being surprised by similar elements in other books, because of being able to see it coming.

There are very few books I would literally tell people not to read unless they’ve read a certain list of other books. This is one of them.

@34

With all respect, I am deeply uncomfortable with any argument that says that you should not read x until you have read w*. It is possible to appreciate a book on its own merits and then discover that it is a reaction to other books which then deepens your appreciation. But fundamentally, I want a very good reason before I’ll tell someone ‘you should not read this book’.

*allowing for obvious exceptions like The Wide Sargasso Sea, a ‘prequel’ to Jane Eyre. And Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead really doesn’t work if you haven’t seen Hamlet.

I was probably about 13 when I read Childhood’s End, and I was comfortable with the ending. I expected big strange things in happen in sf, there were gaudy colors (as I recall), and I wasn’t that fond of the world anyway. (Probably just as well that I wasn’t in charge, but you could have bought me off with a ticket to Shangri-La.)

Decades later, it occurred to me that the Overmind’s concern with human research into parapsychology leading to a “cancer spreading among the stars” just might be an excuse for eliminating competitors, aside from any issues about the destruction of the human race. (IIRC, The Forge of God is much more elegaic about the destruction of nature than Childhood’s End is.)

The weirdest thing about Childhood’s End might be that it’s a novel in which no human decision makes the slightest difference to how it ends, and yet it’s a novel which appeals to a general audience rather than a literary experiment.

I read Childhood’s End a zillion times as a kid. A lot of SF books didn’t age well for me so I hesitated to reread it, but I did and it’s still great.

As for having to be familiar with SF to enjoy this book, no you don’t, although I agree you have to be familiar with SF to get all the reasons it’s impressive. I read it when I was quite young and didn’t have a lot of expectations about SF or anything else, but it generated that feeling of awe that I’ve been trying to get by reading SF ever since.

I think it ended up influencing some of my expectations about SF. For example it spoiled me for most SF that doesn’t have really alien aliens, because the scene that stuck with me most was the one where the kid dreams about all the different forms of intelligent life on all the different kinds of planets.

Maybe my grasp on humanity has always been a bit weak. I was really envious of the children.

I encountered Childhood’s End just a few years ago when I found it on Audible; I can assure you, reading it for the first time as an adult is just as amazing an experience as reading it in childhood might have been for me and was for so many others. The only regret I have is not having discovered Clarke sooner; I have a lot of catching up to do, and a lot less time to do it in. In your opinion, what other books by Clarke would serve as a good jumping off point. Is there anything else as exciting and imaginitive as this one?

LibraryTechChick@38: You simply must read The City and the Stars. That and Childhood’s End are Clarke’s best works, as far as I’m concerned — the ‘sense of wonder’ those two invoke in me has never been surpassed by other writers, even Niven with his Ringworld. There’s just something about Clarke.

I have all of his works, and of them, Rendezvous with Rama is excellent — a story of investigation and exploration with no Enemy to fight … just a strange artefact and the team that explores it. 2001: A Space Odyssey needs no introduction.

I know I have read The Songs of Distant Earth, but that was so long ago that I no longer remember it. Clarke said it was his favourite, however, so there you go.

There are others, of course, and you will find them, and you should read them. But I would also recommend reading his short stories, which are uniformly excellent, and are available in a number of collections. Tales from the White Hart, The Nine Billion Names of God, The Other Side of the Sky, and Expedition to Earth are the best of these collections; I read them over and over again as a teenager.

Enjoy!

… Oh, and, by the way, the sequels to 2001 are probably best ignored (perhaps 2010, but …) and just stay away from any of the later collaborations — especially anything involving Gentry Lee. I simply never bothered to read anything of his after about 1990, figuring that, by that time, his input was fairly minimal anymore anyway.

I reread this after enjoying this recap. I only vaguely remember my response the first time I read it as a teen as being seriously impressed and kind of sad. This time it was even more upsetting, and several times I kept saying “Why am I even reading this? I knew this was going to happen!” I cried for the parents of the children at the end (having kids of my own has made me hypersensitive). It really is one of a kind, and I still, after all these years, don’t know if I like it or not.

First read Childhood’s End at age 12, and I reread it every 6-7 years or so. Last time around, I finally caught the cute bit of dialogue in chapter 2, when Van Ryberg asks Stormgren, referring to Supervisor Karellen, “Why the devil won’t he show himself?”

I read this book first when I was 17. I’ve read it once every couple of years since then. I am 61 now. It’s odd that I have never found it depressing – at 17 it seemed ineffably beautiful . Of course, the late 60s were a time of cosmic wonder , for some of us at least, and perhaps we were more amenable to such ideas then. I gave it to my daughter when she was a teenager and she liked it , loved it, but found it depressing. I’ve never been able to find authors other than Clarke and Bradbury that gave me those same awed goosebumps. Robert Charles Wilson has come close though and I follow his career with great interest.

This is by far one of my favorite stories. I like the perspective and commentary of the reveiwer, but for f’s sake, he actually gives the entire story away almost instantly. You can only read a book the first time, once. Why ruin the premise for the first time reader?

tstoneami, I don’t think Jo gives anything away in this review, other than the general shape of the plot and feel of the book, which is the sort of thing a review is for. And, TBH, _Childhood’s End_ was published in *1953*. I don’t think it counts as spoilage to give away the ending of a book published over *sixty years ago*.

(And Jo Walton is a lady, known for excellent writing, also for excellent hats. IMHO anyway.)

When you take a step back from Childhood’s End, the big picture looks like an artists rendering of the relationship between angels and humanity. Our worldly passions are quieted, our bodies stilled and our souls readied for a rapture to whom the angels serve. From the point of terrestrials, it is horrific giving up our sense of reality. But the end of the book was not an end of anything but childhood; maturity takes place beyond terrestrial comprehension. It’s an admirable story for eliciting and capturing in each reader’s mind that frightening and wondrous moment when emotions split on experiencing letting go and moving on.

My father had a short story collection by Clarke (Probably because we lived in the same country as Clarke was living). This was among the first English books I read. They were ok. Sometime later (I think I was 16 or 17) I stumbled upon City and the stars in an old bookshop. I think I read the book back to back twice. Nothing else had come close to evoking in me the sense of awe and sheer wonder that that book did.

I read Childhood’s End (CE) just yesterday. After my early days of reading Clarke, I forgot him. His later books were crap anyway. And I thought he was too dry for me. Now having read CE, I am pretty sure that he probably has to be the best at tackling grand themes. I hate sci-fi when they deal with petty subject matter. What purpose does it serve to discuss purple colored shit? CE sort of transported me back to my childhood – when dreams were as real as reality and that longing for the future and for more came back. Well, It’s one hell of a book.

To the above points..

1) The human race did not end, that was the whole point of the book, any more than a caterpillar ends when it becomes a moth.

2) Karellan was the main character and he was a great one. The ending is sad, not because of what happened to humanity, but because the Overlords are cut off from the real essence of life in the universe.

3) Jan was a great character. What’s this about no characters in Clarke? Ever read “Meeting With Medusa”? Howard Falcon Scott, great character.

This book needs someone with Kubrick’s vision to make it into a film. It can be done, but the bros in Hollywood like Fincher, or Cameron, forget it. Maybe Terence Malick.

-dr