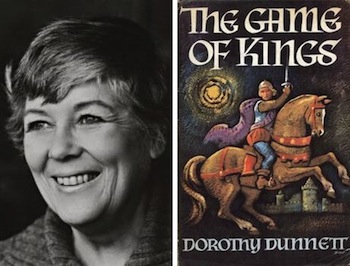

Dorothy Dunnett is one of those authors you hear about through word of mouth. She didn’t write fantasy—unless you count taking sixteenth-century belief in astrology as true from the perspective of her characters—but ask around, and you’ll find that a surprising number of SF/F authors have been influenced by her work. The Lymond Chronicles and the House of Niccolò, her two best-known series, are sweeping masterpieces of historical fiction; one even might call them epic. And indeed, writers of epic fantasy could learn a great many lessons from Lady Dunnett. Here are but five, all illustrated with examples from the first book of the Lymond Chronicles, The Game of Kings.

1. How to Use Omniscient Narration

Most epic fantasy novels these days are written in multiple third limited, shifting from character to character to show events in different places or from different angles. Given that epic fantasy is expected to range across a broad sweep of locations and plots, it’s a necessary device.

Or is it?

Omniscient perspective may be out of style these days, but reading through the Lymond Chronicles, I keep being struck by how useful it is, especially to the would-be writer of an epic. I don’t mean the type of omniscience you may remember from children’s books, where the narrator is talking to the reader; that usually comes across as twee, unless you have a very good context for it. I mean the sort that has full range of movement, sometimes drawing in close to give you a certain character’s thoughts for an extended period of time, other times shifting to give you several perspectives on the scene, and occasionally pulling all the way back to give you a god’s eye view of events.

The benefit this offers to an epic fantasy writer can be demonstrated any time Dunnett has to discuss the larger board on which her pieces are moving. She can, with a few elegantly-written paragraphs, remind the reader of the political and military forces moving in France, Spain, England and Scotland—and she can do it actively, with lines like this one:

“Charles of Spain, Holy Roman Emperor, fending off Islam at Prague and Lutherism in Germany and forcing recoil from the long, sticky fingers at the Vatican, cast a considering glance at heretic England.”

The plain expository version of that would be a good deal more dull, robbed of personality and movement, because it could not show you what the Holy Roman Emperor was doing: it could only tell you. To liven it up, the writer of third limited would need to make her characters have a conversation about Spanish politics, or else jump to a character who’s in a position to see such things on the ground. And that latter choice offers two pitfalls of its own: either the character in question is a nonentity, transparently employed only to get this information across, or he gets built up into a character worth following… which rapidly leads you down the primrose path of plot sprawl. (I was a longtime fan of the Wheel of Time; I know whereof I speak.)

But the omniscient approach lets you control the flow of information as needed, whether that’s the minutiae of a character’s emotional reaction or the strategic layout of an entire region as armies move into position. In fact, it permeates everything about the story, including many of my following points—which is why I put it first.

2. How to Write Dynamic Politics

I will admit that Dunnett had a leg up on her fantasy counterparts where politics are concerned, because history handed her a great deal of what she needed. For example, she didn’t have to invent the ambiguous loyalties of the Douglas family, playing both sides of the game at once; she only had to convey the result to the reader.

Of course, if you think that’s easy, I have some lovely seafront property in Nebraska to sell you.

Real politics are hard. I’ve read any number of fantasy novels where the political machinations have all the depth of kindergartners arguing in a sandbox, because the writers don’t understand how many variables need to go into the equation. Dunnett understood—and more importantly, was good at conveying—the interplay of pragmatism, ideology, and personal sentiment that made up actual history. There’s one point in The Game of Kings where two characters have a remarkably level-headed conversation about the three-cornered political triangle of England, Scotland, and France, and one of them lays out a hypothetical scenario that might, if followed, have averted a lot of the troubles of the later Tudor period. The dry response: “It isn’t any use getting intelligent about it.”

It doesn’t matter how good an idea is if you can’t make it happen. And the things that can get in the way are legion: lack of supplies, or supplies in the wrong place to be of use. Ideological conviction that won’t back down. Even just two individuals who loathe one another too much to ever cooperate, despite the benefit it would bring to them both. When I was studying the politics of the Elizabethan period for Midnight Never Come, there was a point where I threw my hands up in the air and said “they’re all a bunch of high school students.” Cliquish behavior, pointless grudges, people flouncing off in a huff because they don’t feel properly appreciated—it’s sad to admit, but these are as much a cause of strife as grand causes like nationalism or the need for resources.

Dunnett keeps track of these things, and makes sure they slam into one another at interesting angles. You could map out the plots to her novels by charting the trajectories of various personalities, propelled onward by loyalty or obligation or hatred or simple irritation, seeing where each one turns the course of another, until it all reaches its conclusion.

(And, as per above: her ability to step back and convey the larger political scene through omniscient perspective helps a lot.)

3. How to Write a Fight Scene

I’ve studied fencing. I’m just a few months away from my black belt in shorin-ryu karate. I used to do combat choreography for theatre. Fight scenes are a sufficiently major interest of mine that I’ve written an entire ebook on how to design them and commit them to the page.

And I’m here to tell you, The Game of Kings contains the single best duel I have ever read in a novel.

It is good enough that I’ve used it as a teaching text on multiple occasions. I won’t say that every fight in fiction should be exactly like it; scenes like that should always fit their surrounding story, and if you aren’t writing a story like Dunnett’s, you’ll need to vary your approach. She’s writing in omniscient; that means she can set the scene from the perspective of a camera, then shift throughout the duel to show us the thoughts of the spectators or the combatants, all the while keeping the motives of her protagonist tantalizingly opaque. A first-person fight would read very differently, as would a scene depicting armies in the field. But regardless of what kind of fight you’re trying to describe, you can learn from Dunnett.

Can you think of a descriptive element that might make the scene more vivid? It’s in there, without ever reaching the point of distraction for the reader. Want high stakes? Oh, absolutely—at every level from the individual to the nation. She ratchets up the tension, changes the flow of the duel as it progresses, and wraps it all up in beautiful narration. It’s gorgeous.

I can only hope someday to produce something as good.

4. How to Write a Good Gary Stu

“Gary Stu” doesn’t get thrown around as often as its sister term, “Mary Sue”—probably because we’re more accustomed to watching or reading about good-looking, uber-talented guys who accrue followers without half trying. But characters of that sort are rarely memorable on an emotional level: we love watching James Bond beat up bad guys, but how often do you think about his inner life? How much is he a person to you, rather than an idealized archetype?

I will be the first to admit that Lymond is a dyed-in-the-wool Gary Stu. But he’s also a fabulous character, and I want to pick apart why.

Some of it begins with Dunnett’s manipulation of point of view. Remember how I said her omniscient perspective shifts from place to place, constantly adjusting its distance? Well, in The Game of Kings she pulls a remarkable stunt: the one perspective she doesn’t give you is Lymond’s. The whole way through the book, the closest you get to his head is the occasional fleeting touch.

I wouldn’t recommend trying this nowadays; your editor would probably think you’ve lost your mind. But it does demonstrate the value of seeing your Gary Stu or Mary Sue through someone else’s eyes, which is that it makes admiration for them feel more natural. If I were in Lymond’s head while he makes people dance like puppets, he would either feel arrogant, or (if downplaying his own achievements) obtrusively modest. Seeing it from the perspective of other characters gives you more distance, and room to explore their various reactions. They can be impressed by what he’s doing, even when they’re afraid or annoyed or trying to stop him.

Which brings me to my second point: Lymond is flawed. And I don’t mean the sort of flaws that usually result when a writer gets told “you need to give your protagonist some flaws.” He doesn’t have a random phobia of spiders or something. No, he’s the one character whose story has ever made me feel like a weak-kneed fangirl, while simultaneously wanting to punch him in the face. And better still, sometimes the people around him do punch him in the face! And he deserves it! Lymond has a vile temper, and also a tendency to distract people from his real goals by being a complete asshole at them. So any admiration of his talents is distinctly tempered by the way he employs them.

The third aspect is the real doozy, because it requires a lot of hard work on the part of the author: despite his brilliance and countless talents, Lymond still fails.

Time and again throughout the series, Dunnett engineers scenarios that are too much even for her amazing protagonist. He has a good plan, but something he didn’t know about and couldn’t account for screws him over. He has a good plan, but it hinges on the assistance of other people, and one of them doesn’t come through. He has a good plan, but even his superhuman endurance can’t get him through everything and he is passed out cold at a key moment.

These aren’t cosmetic failures, either. They carry real cost. When Lymond says “I shaped [my fate] twenty times and had it broken twenty times in my hands,” you believe him, because you’ve watched it shatter once already. And when he achieves a victory… he’s earned it.

5. How to Include Women

Since Dunnett is writing historical fiction, with no fantasy component, it would be easy to let it pass without comment if her story included very few women. Instead the opposite is true—and she does it all within the bounds of realistic history.

Sure, there are a few characters who are of the “exceptional” type we usually think of in this context. The later books of the Lymond Chronicles, for example, contain an Irish revolutionary and a diabolically clever concubine. But around them are a lot of other women who are perfectly ordinary, and more or less reasonable for their period.

Take, for example, Kate Somerville—much beloved of many fans. What is her role in The Game of Kings? She runs her family’s household on the English side of the Scottish border. But that means she’s responsible for taking care of a wounded guest… and she manages to get more out of Lymond than most of the guys who try for it. Plus, if you think she’s blind to the politics that could light her house on fire at any moment, you don’t have a very realistic impression of historical life. Or consider Agnes Herries, the thirteen-year-old Scottish heiress who reads like a hard-headed version of Sansa Stark: her indulgence in romantic fantasies is a deliberate counter to her awareness that her value is in her inheritance. Agnes could have been a side note, but she plays a role that is all the more pivotal for being understated.

I could list more. Richard’s wife Mariotta, who makes a foil for Janet Beaton: one of those women plays an effective role in politics by way of her husband, and the other does not. Margaret Lennox, one of the aforementioned Douglasses and one of the biggest threats to Lymond’s life and sanity, without ever putting her hand on a weapon. Sybilla, Lymond’s mother, who gives you a very clear sense of where Lymond got his brilliance from, and uses her own to great effect. Christian Stewart, who despite being blind is absolutely vital to the story on every level. Their attitudes at time veer a little bit out of period—not entirely modern, but perhaps more eighteenth century than sixteenth—but the actions they take aren’t unreasonable for the time. And they are also relevant, interesting, and effective.

It can be done.

Oh, and did I mention? The Game of Kings was Dunnett’s first published novel.

If you like stories that balance grand political action against intense character drama—or if you want to write such things—her historical novels are absolutely worth picking up. I won’t claim it’s easy to get into; she has a tendency to leave things for the reader to infer from surrounding clues (which has famously resulted in many first-time readers of The Game of Kings wailing “BUT WHY IS THE PIG DRUNK???”). She also likes to quote things in foreign languages without translating them. But once you get the hang of her style, there is so much to admire; I envy anyone who is about to discover her work.

If you like stories that balance grand political action against intense character drama—or if you want to write such things—her historical novels are absolutely worth picking up. I won’t claim it’s easy to get into; she has a tendency to leave things for the reader to infer from surrounding clues (which has famously resulted in many first-time readers of The Game of Kings wailing “BUT WHY IS THE PIG DRUNK???”). She also likes to quote things in foreign languages without translating them. But once you get the hang of her style, there is so much to admire; I envy anyone who is about to discover her work.

This article was originally published in June 2015.

Marie Brennan is the author of multiple series, including the Lady Trent novels, the Onyx Court, the Wilders, and the Doppelganger duology, as well as more than forty short stories. The Varekai series of novellas—Cold Forged Flame and Lightning in the Blood—is available rom Tor.com Publishing. More information can be found at her website.

Marie Brennan is the author of multiple series, including the Lady Trent novels, the Onyx Court, the Wilders, and the Doppelganger duology, as well as more than forty short stories. The Varekai series of novellas—Cold Forged Flame and Lightning in the Blood—is available rom Tor.com Publishing. More information can be found at her website.