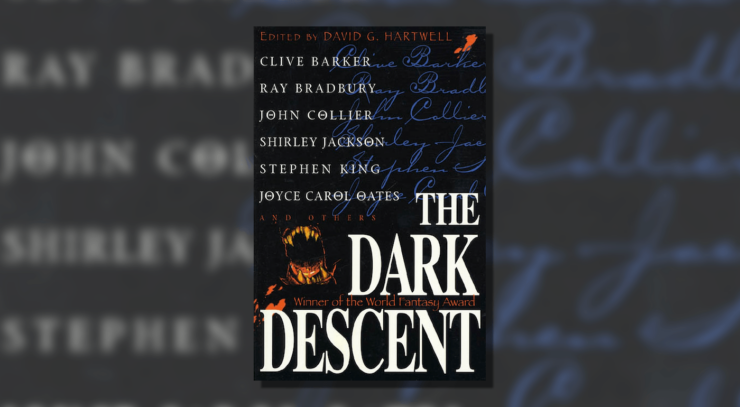

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

Few names are as synonymous with the American Gothic as Nathaniel Hawthorne. In his numerous stories and novels about Puritan America, Hawthorne used Gothic novel tropes and ambiguously supernatural events, America’s own shadowy history, pockmarked with evil acts, and commonly known metaphors to fashion moral allegories about social pressure, judgment, and the torment of moral perfection. All of this is exemplified in “Young Goodman Brown,” Hawthorne’s oft-discussed (and often parodied) American folk horror tale that takes aggressive aim at the ideas of self-flagellation and worship at the altar of a binary morality.

It’s a work that manages to be both unsubtle in its metaphor and yet sly in its intent, snapping its protagonist’s psyche in half under the weight of his polarized belief in absolute good and evil, and examining morality and judgmental thinking in the process.

An enterprising young man of Salem named Goodman Brown leaves his village one fine evening for an unspecified appointment in the woods. Upon reaching the man he’s supposed to see, their conversation takes them deeper into the dark woods, the man revealing himself to be none other than Satan. Now convinced he’s locked in a battle for his very soul, Goodman Brown struggles to keep his virtue as the woods grow more surreal, meeting fellow townspeople who seem very well acquainted with his traveling companion. Lost in the deep, dark woods, Goodman Brown is further ensnared in Satan’s plans, culminating in a Satanic mass featuring his neighbors and loved ones that tests his soul, will, and sanity.

The story shares much in common with other versions of the familiar “Devil’s meeting” trope, where a protagonist meant to represent the average person happens upon a Satan figure in the woods and has their morality and faith tested. The most obvious examples of these are fairy tales, in which good children who don’t stray from the path are rewarded, and those who behave badly or refuse to listen to their parents are punished severely. The significant difference “Young Goodman Brown” introduces is that Brown’s choices aren’t what damn him but his inability to see humanity in others. It’s clear throughout that the story isn’t on Brown’s side any more than it’s on the side of the Devil, but that his thought—either people are perfect and free from sin or they’re miserable sinners—is a useless and false dichotomy.

Hawthorne’s Satan comes right out and implicates Brown’s family in two major Colonial Era atrocities; the burning of Indigenous villages, and the Salem witch trials. Hawthorne goes right for the heart with it, setting Brown’s belief in his own faith and goodness against his ancestors’ complicity in acts of sexism, racism, and genocide. In doing so, he takes aim at the underlying hypocrisy, that someone can be of good faith and morals and think that means they’re free from sin. After all, the townspeople are godly, and yet their entire society is built upon atrocity and bloodshed. All the Devil does is use this hypocrisy and guilt to torment Brown, weaponizing his polarized method of thinking to shatter his mind and show him how hollow his purity really is. His inability to reconcile the idea of “goodness” with his family’s willful participation in atrocity, with his own racism and participation in an oppressive society, puts him constantly at odds with himself.

You could be forgiven for thinking this was a straightforward tale about a man finding out that all his neighbors are sinners and the world is an evil place. That’s certainly an interpretation, and a common one. Where it gets interesting (and where the straightforward interpretation falters) is with what the Devil actually says in the text when he meets Goodman Brown:

“…I have been as well acquainted with your family as with ever a one among the Puritans …I helped your grandfather, the constable, as he lashed the Quaker woman through the streets of Salem, and it was I that brought your father a pitch-pine knot, kindled at my own hearth, to set fire to an Indian village in King Philip’s War. They were my good friends, both …I have a very general acquaintance here in New England.” (p. 134)

Hawthorne’s Satan comes right out and implicates Brown’s family in two major Colonial Era atrocities; the burning of Indigenous villages during King Philip’s War, and the persecution of Quakers. Hawthorne goes right for the heart, setting Brown’s belief in his own faith and goodness against his complicity in acts of sexism, racism, and genocide. In doing so, he takes aim at the underlying hypocrisy, that someone can be of good faith and morals and think that means they’re incapable of doing evil. All the Devil does is use this hypocrisy and guilt to torment the man, weaponizing Brown’s polarized method of thinking to shatter his mind and show him how hollow his purity really is.

It breaks Goodman Brown. He finds himself front-and-center at a Satanic mass. The idea that his neighbors are sinners, that his family are sinners, that he is a sinner despite believing in God and faith every step of the way, is too much to bear. The end of the story finds him a paranoid wreck, cold to everyone around him because all he can see are the sins committed by his friends and family. He breaks not because the world is filled with sin and he can’t handle it, but because the rigid definitions of “sin” and “goodness” can’t actually stand up against human moral complexity. It’s not viable to expect people to lead lives of perfect purity any more than it is to condemn them for being dark and evil merely because they don’t meet some ideal moral standard. The world isn’t the place full of goodness and purity that Goodman Brown thinks it is before his sojourn into the woods, but nor is it the vast den of iniquity he believes after he returns.

Instead, if he were able to reconcile the guilt he felt, to use it in a more constructive manner and maybe see human beings as, well, human, he might have had a chance of surviving his night in the woods. Humanity (very much including white people, lest we lose focus on Brown’s particular set of prejudices and privileges) can be capable of evil, it’s true. But misanthropy is just as useless and fatuous here as ultimate goodness. Neither actually bothers to interrogate humanity, to allow one to grow and change and reconcile their sins (past and present) to truly be a better person instead of just believing they’re incapable of sin. Only in managing to examine the sins of our pasts and truly accepting guilt, not merely using it to beat ourselves up, can we actually escape the twin pitfalls of impossible virtue and sneering misanthropy.

It’s a recurring theme in Hawthorne’s work, illustrated beautifully out of the guilt, repression, and self-flagellation of the Puritans—his characters are complex people caught within a larger system of morality. They judge others (and are judged themselves) on the weight of their sins, punishing themselves for their very humanity rather than admit that their conception of a “godly life” is poisonous. In his works, it’s that inability of his characters to see humanity that causes them physical and psychological torment, instead fixating on their own sin, guilt, and the idea of divine punishment. In “Young Goodman Brown,” this plays out with the Devil tormenting its “good Puritan” main character by showing his friends and loved ones as wicked sinners, with the narration even suggesting that the entire journey through the woods was nothing more than Brown’s guilt-induced dream as he slept among the trees.

The way out of Hawthorne’s dark woods, the way to beat his Devil, is to abandon the Puritanical black-and-white system of morality and its snarling judgments. That doesn’t mean “all morals are relative” any more than it means “everyone is a sinner.” Brown’s ultimate misanthropy and rejection of all “evil” is just as miserable and damaging as the Devil’s pronouncements at the story’s climax that all the “good people” of Salem are wicked and horrible sinners. In no way, shape, or form does this mean that people shouldn’t be held accountable for their sins and wrongdoing, but in characterizing people as merely “good” or “evil,” you get a society of miserable hypocrites and misanthropes obsessed with being “perfect” instead of good, punishing sinners while concealing their own sins and praying they aren’t discovered.

“Young Goodman Brown” is about reckoning with both the light and dark sides of our humanity, reconciling our guilt, and dismantling systems of moral oppression that drive us to torture ourselves and others. In the end, the only question left for Goodman Brown is “Why would you do this to yourself? Why would you do this to those around you?”

It’s a chilling question, but an important one.

Please join us in two weeks as we spend time with yet another pivotal figure in gothic fiction, J. Sheridan Le Fanu and his story “Mr. Justice Harbottle.”

Sam Reader is a literary critic and book reviewer currently haunting the northeast United States. Apart from here at Tor.com, their writing can be found archived at The Barnes and Noble Science Fiction and Fantasy Book Blog and Tor Nightfire, and live at Ginger Nuts of Horror, GamerJournalist, and their personal site, strangelibrary.com. In their spare time, they drink way too much coffee, hoard secondhand books, and try not to upset people too much.