So—shock of shockers here, I know—I really like Ted Chiang, and not just because he’s got really awesome hair and is proof that it’s still possible to amass a very good reputation as an SF writer while sticking to a focus on short work. My favorite story of his to date is “Stories of Your Life,” which may have made me have to find a Kleenex quickly.

In short, I jumped at the opportunity to review his new novella from Subterranean, The Lifecycle of Software Objects.

This? Ladies and gentlemen, this is a very peculiar little book, and I mean that in the absolute best way possible. Chiang gives us a rapid overview of the evolution and abandonment of a species of digital pet that may—or may not—be evolving artificial intelligence, and a very cogent overview of how people might respond… the ones that even notice.

I don’t normally look to Chiang’s work to give me renewed hope for humankind, but somehow this story did so. I also don’t usually apply adjectives like “adorable” to his work—especially when it includes a frank assessment of the sexual applications of nth-generation virtual pets—and yet, here we go. This is an adorable little book. In some ways, it almost feels like a children’s story.

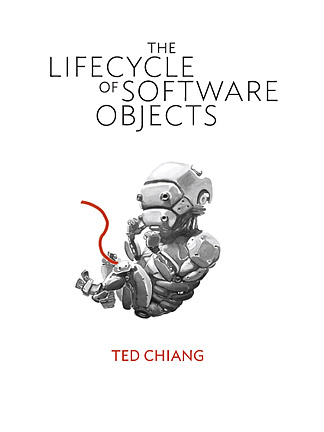

The illustrations contribute to that—at least until you reach the fairly graphically sexual one. I admit, I was reading this book in a public place, and I muffled the portrait of human/virtual pet oral sex with the dust jacket until I had turned that page. I’m too much of a coward to explain that one to a strange six-year-old’s mother.

In part, that sense of innocence and naivete is maintained because Chiang narrates it in such a pellucid, bare-bones style. This is a story more told than shown, and I think it benefits from that treatment. While it removes the possibility of the reader’s visceral emotional response, it allows a certain clarity that I don’t think would emerge if we were more potently connected to the characters.

But I think most of makes this feel like a children’s story is that everybody in it is so darned earnest. The human protagonists—Ana Alvarado and Derek Brooks—are profoundly decent people, and their “digient” research subjects are like human toddlers without the poo and tantrums. Everybody in this book means what they say: there is no irony, no subterfuge, no self-delusion. Even when they manipulate each other, they’re right up front about it.

There’s also a distinct lack of physical grounding throughout the story, which contributes to its feel of taking place in a virtual world. And Chiang’s portrayal and analysis of the social problems caused by a no-longer-trendy potential AI platform are incisive. I believe in the software development process in this book—the abandonment of one idea to pursue another with equally limited results, the creation of idiots savants and virtual toddlers.

The problems the human guardians of the digients have in allowing their charges a measure of self-determination will be poignant to anyone who had ever had charge of a child—or even a pet. How many mistakes do you let them make? How much self-determination can you allow something or someone that doesn’t quite understand all the dangers that surround them?

This is a descriptive work of science fiction, rather than a strongly plot-driven one. It’s meditative and thoughtful, and it does not offer tidy closure or resolution: just a series of ever-more-complicated questions.

Very nice work indeed.

Elizabeth Bear is the Hugo and Sturgeon Award winning author of many books and short stories.