Shared universes! The practice of having multiple authors write works in a common setting is a well-established one. No surprise, because shared universes offer a variety of benefits to participating publishers and authors, from being able to farm out specific creative tasks to those most suited to them, to providing a backdrop for series whose commercial value is proven1.

Oh, and I should also note that humans have been riffing on plots/characters/tropes that they didn’t create for millennia. Think of all the versions of “Cinderella” out there. SFF has done this too—fantasy, in particular, seems to have long been fond of riffing on common fairy tales and folklore. SF was slower to adopt shared universes, though the 1952 Twayne Triplets, discussed here, bordered on the concept. Shared universes eventually took off and enjoyed a golden age from the late 1970s through the 1980s2.

Here are some examples, starting with the 1970s…

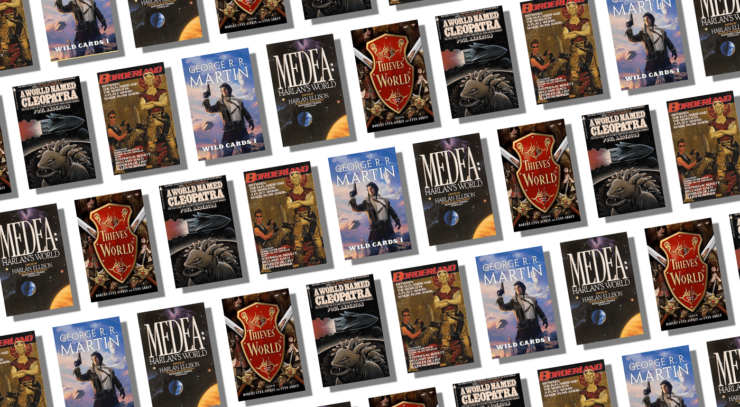

A World Named Cleopatra, edited by Poul Anderson, produced by Roger Elwood (1977)

Master worldbuilder Anderson provided contributors with a setting, a planet both surprisingly Earth-like and inconveniently alien, scribed an introductory tale himself, then invited Michael Orgill, Jack Dann, and George Zebrowski to enjoy the playground he’d created. Together, they document the rise and fall (and hope of renaissance) of the human settlement on Cleopatra.

No surprise to see Anderson’s name here, although his editorial role was an unusual one for him. He contributed to a number of shared worlds, including the Twayne Triplets. Clearly, the form appealed to him.

While A World Named Cleopatra shows something was in the water where Disco Era shared world prose anthologies were concerned, Cleopatra was a one and done. Perhaps no further volumes were planned. Perhaps the unattractive cover failed to catch readers’ eyes. Perhaps it was because the mid-1970s were a particularly gloomy time for Anderson and the anthology reflects this, beginning with the Carlyle epigram at its beginning:

“A sad spectacle (the stars). If they be inhabited, what a scope for misery and folly.”

Ah well. That’s still more upbeat than Anderson’s story “The Pugilist.”

Medea: Harlan’s World, edited by Harlan Ellison (1985)

With roots in a 1975 UCLA seminar (“Ten Tuesdays Down a Rabbit Hole”), Ellison’s project was in all ways more ambitious than Anderson’s. Where Cleopatra made do with one worldbuilding essay, Ellison commissioned four essays to paint his gas giant’s moon setting. The essayists were Anderson, Clement, Niven, and Pohl. There was also considerable ancillary material. Where Cleopatra had four authors, Medea had eleven: Jack Williamson, Larry Niven, Harlan Ellison, Frederik Pohl, Hal Clement, Thomas M. Disch, Frank Herbert, Poul Anderson, Kate Wilhelm, Theodore Sturgeon, and Robert Silverberg. Cartography was by Diane Duane, with illustrations by Frank Kelly Freas. No surprise that the tome weighed in at over five hundred pages.

What prevented Medea from kicking off the shared world universe boom likely boils down to the publication date. Inexplicably for an ambitious Ellison anthology, progress between inspiration and final product appears to have been glacial… Many of the stories saw first print in magazines long before Medea appeared on bookshelves3. Delay appears to have cost Ellison his chance to inspire the shared universe golden age, as dangerous a vision as that seems. Nevertheless, Medea is worth tracking down just for the essays.

Thieves’ World, edited by Robert Asprin and Lynn Abbey (1979)

Thieves’ World (fantasy rather than science fiction) introduced readers to Sanctuary, a once-great trading community whose decline and isolation made it an ideal destination for refugees and rogues, as well as a convenient oubliette in which to immure superfluous royals. Thieves’ World didn’t offer the same obsessive meticulous world-building as did Cleopatra or Medea; the editors made a point of keeping details vague in order to provide authors with greater scope for creativity. It did feature a cross section of respected names of the era: Robert Asprin, John Brunner, Lynn Abbey, Poul Anderson, Andrew J. Offutt, Joe Haldeman, Christine DeWees, and Marion Zimmer Bradley.

In addition to the SFF Who’s Who in the table of contents, Asprin and Abbey made a couple of judicious decisions. First, their setting was fantasy, at a time when fantasy’s popularity was soaring. Second, while the stories were often grim, the essays convey infectious enthusiasm about the project. Third, perhaps most importantly, the pair immediately followed up the first volume with further volumes to capitalize on the success of the first.

It’s hard to put a firm number on the quantity of follow-up volumes. There were twelve anthologies in the original 1979–1989 series, in addition to which there were two anthologies much later, in the 21st century. There were seven official novels, at least nine collections and novels related to greater or lesser degree, and a roleplaying game adaptation.

And now, let’s turn to the 1980s…

Success invites imitation. Much to the irritation of editor/anthologist Gardner Dozois, who often took page space in his annual Best SF anthologies to complain about the phenomenon, a golden age of shared universe anthologies followed. Examples include Temps, The Weerde, Villains, Liavek, The Fleet, Heroes in Hell, Merovingian Nights, Man-Kzin Wars, and many more. So many more.

Some of these efforts were good. Others possessed positive qualities too subtle to easily summarize or in some cases, detect at all. There were sufficient shared world projects for every taste and age. For an idea of the range, consider these two series.

Borderland, edited by Terri Windling and Mark Alan Arnold (1986)

Having absented itself from the human realm for centuries, Faerie re-impinges on the mortal world at the Borderland. Neither magic nor technology work reliably in the Borderland. Governance and law enforcement are likewise unreliable. Thus, it’s a perfect refuge for people from both Faerie and America, as detailed by Steven R. Boyett, Terri Windling (writing as Bellamy Bach), Charles de Lint, and Ellen Kushner.

Unlike most of the other series of the time, Borderland was aimed at teen readers. While the series was not as voluminous as some (four volumes in the main series, as well as three novels, and even an RPG!), subsequent volumes attracted such luminaries as Neil Gaiman, Patricia A. McKillip, and Jane Yolen. These days, it’s easy to find testimony from readers young at the time for whom the Borderlands series filled an important need.

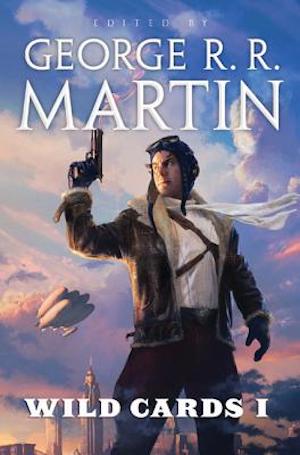

Wild Cards edited by George R.R. Martin (1987)

As documented here, Wild Cards is ultimately the late Steve Perrin’s fault. Having invested creative energy playing Perrin’s Superworld tabletop roleplaying game to the exclusion of other (paying) projects, editor George R.R. Martin prudently monetized his hobby by turning it into a shared world. Edward Bryant, Leanne C. Harper, Stephen Leigh, George R.R. Martin, Victor Milán, John J. Miller, Lewis Shiner, Melinda M. Snodgrass, Howard Waldrop, Walter Jon Williams, and Roger Zelazny painted a vivid four-colour picture of a world transformed by an alien bioweapon, in which uncanny abilities are used for good and ill.

Two things stand out in these volumes. Having been provided by Martin with a single source for all superhuman abilities—transformation by alien virus—Martin’s contributors cheerfully proceeded to create heroes4 whose abilities were not drawn from the virus: aliens, an android, superlatively trained warriors, and the unpowered Jet Boy, who died just as the virus was released. Also, the series’ longevity is astonishing: more than thirty volumes over the course of five decades.

A hat tip to the upcoming Tales from the Silence shared universe project, the appearance of whose Kickstarter in my inbox made me reflect on the many shared universe series currently clogging my book shelves. The works named above are a few of my favorites. However, I read only a very few of the available series. Which noteworthy examples were overlooked? Let us know in the comments below.

- Technically, I suppose authors sharing a house name to write series (such as Nancy Drew or Doc Savage) could constitute a shared universe, but that’s not something I will discuss here. ↩︎

- Star Trek deserves more space than I can give it, here. There were a few shared world anthologies such as Myrna Culbreath and Sondra Marshak’s 1976 Star Trek: The New Voyages. Tie-in shared universe works deserve their own essay, to be penned by reviewers who are more up on Trek than I am. ↩︎

- Fred Pohl’s Jem seemed to owe not a small fraction of its worldbuilding to Medea. ↩︎

- Well, let’s say “protagonists” rather than heroes. It is a Martin project, after all. Everyone is grey. Also, I should note that there’s an alarming frequency of sexual violence as plot parsley. ↩︎