With its opening shot of Sputnik in orbit and its milieu of Red Scare paranoia, fallout drills, and cool beatniks antagonizing shady government agents, The Iron Giant was a throwback when it premiered in August of 1999.

All of the rich flavoring director Brad Bird (working off a screenplay he co-wrote with Tim McCanlies) peppers into his debut feature comes directly from the earliest days of his childhood and those of his original audience’s parents. But while the film may reach backwards to 1957, it has gradually become one of the most important superhero movies of the modern era.

I know there are a few potentially controversial statements in that sentence, so let me start to address them, starting with the designation “superhero movie.” Based on the children’s story The Iron Man by British poet Ted Hughes, The Iron Giant features a mysterious alien robot (voiced in the movie by Vin Diesel, long before he am Groot) crash landing outside of Rockwell, Maine, where he befriends young Hogarth Hughes, the son of overworked single-mother Annie (Jennifer Aniston). The two become fast friends after Hogarth overcomes his fear and frees the Giant from downed power lines, but their summertime adventures end when dogged FBI agent Kent Mansley (Christopher McDonald) deems the Giant a national security threat and does everything in his power to destroy it.

Though the setup might sound vaguely X-Men-esque to more modern fans (“creature with fantastic powers protects those who fear and hate him”), the Giant keenly identifies with a different superhero—one who was already an established cultural icon in 1957. Early in their friendship, Hogarth brings the Giant a stack of comic books and introduces the characters. Stopping at a copy of Action Comics, Hogarth points to Superman and says, “He’s a lot like you: crash-landed on Earth, didn’t know what he was doing. But he only uses his powers for good, never evil. Remember that.”

As Hogarth speaks, the Giant notices another comic from the stack, one with a rampaging robot on the cover. “Oh, that’s Atomo, the metal menace,” Hogarth dismissively notes. “He’s not a hero, he’s a villain,” he says before assuring his pal: “But you’re not like him. You’re a good guy, like Superman.”

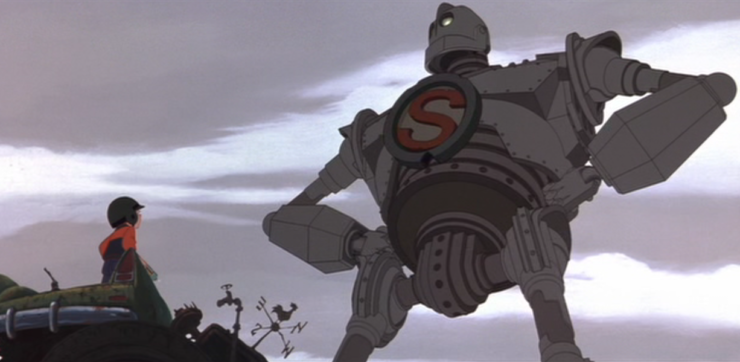

The Giant immediately takes this to heart, and doesn’t even want to pretend that he’s anything else. So when the two of them play in a junkyard, the Giant refuses to take the metal menace role. “Not Atomo,” the Giant sulks, twisting a piece of scrap metal into an “S” on his chest. “I Superman!” the Giant proudly declares. Undeterred, Hogarth plays the villain, pointing his toy gun at “Superman.”

And that’s when everything changes: the Giant’s eyes glow red and we suddenly see Hogarth through his perspective, a target zooming in on the boy and his gun. The enraged Giant fires a real blast, nearly disintegrating his young friend and forcing their beatnik pal Dean (Harry Connick Jr.) to shoo the robot away.“He’s a weapon!” Dean shouts, hurrying Hogarth away from the penitent Giant; “A big gun that walks!”

This central conflict is precisely what makes The Iron Giant a superhero movie. In between the duo’s playful adventures and the comic sequences in which they evade Mansley, The Iron Giant is the story of an incredibly powerful creature deciding what he is. As Mansley and the U.S. government fears, the Giant is a weapon created by some unknown force, capable of destroying the entire country. But he is also, as Hogarth insists, a good guy, capable of heroic deeds like Superman. Who will he choose to become?

The Giant’s struggle mirrors that of both the town and the country as a whole. In the same way that the Giant has a purpose and the ability to carry it out, so also do Rockwell and the United States face a real threat in the form of the Soviets and of the Giant. As Mansley and his commanding officer General Rogard (John Mahoney) insist, they have a duty to protect citizens. As aggressive and fanatical as Mansley can be, he isn’t wrong about the destructive potential of the Giant.

But The Iron Giant suggests that giving into fear doesn’t save the day: It only makes it worse. In the movie’s climax, when the army transforms the heretofore idyllic Rockwell into a war zone, Rogard’s troops attack the Giant even though he’s holding Hogarth, having rescued the boy from a fall that would have killed him. When Rogard decides against launching an atomic weapon at Maine in order to destroy the Giant, Mansley overrides the order and sends the nuke toward Rockwell. Mansley’s proud of himself, certain that he’s done the right thing and saved the rest of America from this invading threat, until Rogard explains that the missile is heading toward the Giant and that the Giant is in the same town as them. “You’re going to die, Mansley. For your country,” sneers the general.

At that moment, the Giant knows what to do. Looking at the rocket arcing across the sky, the Giant orders Hogarth to stay and launches himself into the air to meet the weapon in the atmosphere. As he flies, the Giant recalls Hogarth’s words from earlier in the film, “You are who you choose to be.” His eyes peacefully closing as he nears the rocket, the Giant declares his decision with a single word: “Superman.”

The Giant had every right to run away; he had every reasonable right to defend himself against the army that wanted to destroy him. He even had orders from whomever programmed him to attack his enemies. But he chose to reject that logic. He chose instead to sacrifice himself for the sake of others. He chose to be a hero.

To be sure, there’s enough in this brief outline to reveal clear parallels between the movie and the current state of the U.S. The fear of foreign invaders, a continuous onslaught of sinister outsiders that exists largely in our nightmares, drives both private citizens and government forces to attack and harm others in the name of safety. And as in the movie, the country harms itself in these pursuits, imprisoning those who could enrich it and transforming into something terrifying and hateful.

But The Iron Giant offers more specific message, one who’s relevance in 2019 couldn’t have been predicted by a horror movie, let alone a children’s sci-fi adventure.

The Giant’s journey toward Superman begins early in the movie, after he and Hogarth find two hunters standing over a deer they’d shot. After the hunters run off, the Giant tries to coax the deer into standing, forcing Hogarth to explain to the Giant the concept of death and, more importantly, the concept of guns. “They shot it with that gun,” Hogarth states, trying to underscore the relation between the weapon and death. However, the Giant doesn’t hear, as the sight of the gun triggers his first transformation sequence, his eyes narrowing and starting to turn red. But before he can change further, the unsuspecting Hogarth snaps the Giant out of it by coming to the point of his speech.“Guns kill things,” he states firmly, unaware of the shame creeping across the Giant’s face.

More than a mere morality lesson, Hogarth’s declaration presents an existential quandary for the Giant. He comes to realize that he was designed to be a weapon, and that his purpose was disrupted by the damage he received when he fell to Earth and his programming further counteracted by experiences with Hogarth and Dean. The Giant’s arc is not set against Mansley or Rogard or any earthly force—what could they possible to do him? Instead, it traces his efforts to go against his programming, his struggle to resist the urge to kill in the name of self-defense or inherent nature, and to always choose care over fear.

The Giant temporarily loses that fight towards the end of the film, in which the army’s approach sends him into full attack mode. Overwhelming his enemies with galactic weaponry, the Giant seems lost for good, when Hogarth breaks away from Annie and Dean and runs to face his friend. A wide shot captures Hogarth looking up at the battle-ready Giant, a laser cannon pointed directly at the boy’s face. But in the presence of danger, Hogarth refuses to continue the cycle of violence, refuses to give into fear. Instead, he calls the Giant to be something better: “It’s bad to kill. Guns kill. And you don’t have to be a gun. You are what you choose to be.”

More than just providing the climax to the Giant’s character arc and the setup to his eventual sacrifice, this scene captures the movie’s enduring message. Unlike most science fiction adventure stories, The Iron Giant rejects completely any possible positive aspect to guns. Even when sportsmen legally hunt a deer, and even when Hogarth simply goofs around with a toy laser gun, the movie connects the acts to death and destruction. In the worldview of The Iron Giant, guns kill, period.

The movie never once suggests that the world isn’t scary, or that dangerous people don’t exist. It understands why people own guns and the allure of seeking safety in weapons. But it also believes that sense of safety is a fantasy, as unrealistic as giant robot from space. And that chasing after that fantasy, pretending that guns lead to anything good or heroic or useful, is ultimately destructive. Killing is bad and guns kill.

Four months before The Iron Giant hit theaters in August of 1999, Americans experienced what was the deadliest school shooting at that point in history when two teenagers killed 13 people and injured 21 others at Columbine High School. In the 20 years that have followed, mass shootings have become an almost daily occurrence. Americans mourned after Columbine and wondered how something so horrible could have possibly happened; today, we send kids off with armor plated backpacks, put them through active shooter drills, and offer them hopes and prayers. Worse, we listen to hucksters who say that a bad guy with a gun can only be stopped by a good guy with a gun.

There’s a lot that could be said about how The Iron Giant, which flopped in its initial release, has now become a cult classic because of its top-notch animation, its great voice acting, and its cachet as the first film by a now-beloved director. But the most important reason that The Iron Giant has become the superhero movie of our time has nothing to do with any particular aspect of the film itself. It reached that status because we’ve allowed the country to get so much worse in terms of how we treat one another. We’ve bought into fantasies that violence will stop violence, so much that we now struggle to imagine anything else.

The Iron Giant helps us imagine better. It’s taken twenty years, but we’re just now beginning to see the vital necessity of its simple message. We have to decide who we will be—another weapon, mindlessly acting out of fear, ready to destroy what scares us? Or will we be Superman? The choice, as always, is ours, and it’s a question that grows more pressing every day.

[Editor’s Note: This essay was written, edited, and scheduled to be published before the horrific shootings in El Paso and Dayton over the past two days. After some measured discussion, we decided to publish the article as initially planned, because we believe the perspective and convictions expressed herein are as worthy of thoughtful consideration as they are tragically relevant to the week’s events.]

Joe George‘s writing has appeared at Think Christian, FilmInquiry, and is collected at joewriteswords.com. He hosts the web series Renewed Mind Movie Talk and tweets nonsense from @jageorgeii.