Cosy catastrophes are science fiction novels in which some bizarre calamity occurs that wipes out a large percentage of the population, but the protagonists survive and even thrive in the new world that follows. They are related to but distinct from the disaster novel where some relatively realistic disaster wipes out a large percentage of the population and the protagonists also have a horrible time. The name was coined by Brian Aldiss in Billion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction, and used by John Clute in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction by analogy to the cosy mystery, in which people die violently but there’s always tea and crumpets.

In 2001, I wrote a paper for a conference celebrating British science fiction in 2001. It was called “Who Survives the Cosy Catastrophe?” and it was later published in Foundation. In this paper I argued that the cosy catastrophe was overwhelmingly written by middle-class British people who had lived through the upheavals and new settlement during and after World War II, and who found the radical idea that the working classes were people hard to deal with, and wished they would all just go away. I also suggested that the ludicrous catastrophes that destroyed civilization (bees, in Keith Roberts The Furies; a desire to stay home in Susan Cooper’s Mandrake; a comet in John Christopher’s The Year of the Comet) were obvious stand-ins for fear the new atomic bomb that really could destroy civilization.

In the classic cosy catastrophe, the catastrophe doesn’t take long and isn’t lingered over, the people who survive are always middle class, and have rarely lost anyone significant to them. The working classes are wiped out in a way that removes guilt. The survivors wander around an empty city, usually London, regretting the lost world of restaurants and symphony orchestras. There’s an elegaic tone, so much that was so good has passed away. Nobody ever regrets football matches or carnivals. Then they begin to rebuild civilization along better, more scientific lines. Cosy catastrophes are very formulaic—unlike the vast majority of science fiction. You could quite easily write a program for generating one.

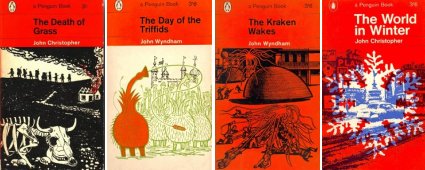

It’s not surprising that science fiction readers like them. We tend to like weird things happening and people coping with odd situations, and we tend to be ready to buy into whatever axioms writers think are necessary to set up a scenario. The really unexpected thing is that these books were mainstream bestsellers in Britain in the fifties and early sixties. They sold like hotcakes. People couldn’t get enough of them—and not just to people who wanted science fiction, they were bestsellers among people who wouldn’t be seen dead with science fiction. (The Penguin editions of Wyndham from the sixties say “he decided to try a modified form of what is unhappily called ‘science fiction’.”) They despised the idea of science fiction but they loved Wyndham and John Christopher and the other imitators. It wasn’t just The Day of the Triffids, which in many ways set the template for the cosy catastrophe, they all sold like that. And this was the early fifties. These people definitely weren’t reading them as a variety of science fiction. Then, although they continued to exist, and to be written, they became a specialty taste. I think a lot of the appeal for them now is for teenagers—I certainly loved them when I was a teenager, and some of them have been reprinted as YA. Teenagers do want all the grown-ups to go away—this literally happens in John Christopher’s Empty World.

I think that original huge popularity was because there were a lot of intelligent middle-class people in Britain, the kind of people who bought books, who had seen a decline in their standard of living as a result of the new settlement. It was much fairer for everyone, but they had been better off before. Nevil Shute complains in Slide Rule that his mother couldn’t go to the South of France in the winters, even though it was good for her chest, and you’ve probably read things yourself where the characters are complaining they can’t get the servants any more. Asimov had a lovely answer to that one, if we’d lived in the days when it was easy to get servants, we would have been the servants. Shute’s mother couldn’t afford France but she and the people who waited on her in shops all had access to free health care and good free education to university level and beyond, and enough to live on if they lost their jobs. The social contract had been rewritten, and the richer really did suffer a little. I want to say “poor dears,” but I really do feel for them. Britain used to be a country with sharp class differences—how you spoke and your parents’ jobs affected your healthcare, your education, your employment opportunities. It had an empire it exploited to support its own standard of living. The situation of the thirties was horribly unfair and couldn’t have been allowed to go on, and democracy defeated it, but it wasn’t the fault of individuals. Britain was becoming a fairer society, with equal opportunities for everyone, and some people did suffer for it. They couldn’t have their foreign holidays and servants and way of life, because their way of life exploited other people. They had never given the working classes the respect due to human beings, and now they had to, and it really was hard for them. You can’t really blame them for wishing all those inconvenient people would…all be swallowed up by a volcano, or stung to death by triffids.

The people who went through this didn’t just write, and read, cosy catastrophes. There were a host of science fictional reactions to this social upheaval, from people who had lived through the end of their world. I’m going to be looking at some more of them soon. Watch this space.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.