As I’ve noted, after the death of L. Frank Baum, Oz had no shortage of writers willing to continue the Oz tales or speculate about various matters in Oz, both past and present, to fill in gaps, or simply add more rollicking tales to the Oz canon. But most of these writers had one thing in common: they accepted Oz unquestionably. If they occasionally took a different moral or political stance (notably Ruth Plumly Thompson) they did not argue with most of Baum’s fundamental points. In the mid-1990s, however, a small book came along that, despite displaying a genuine love of and fondness for the original series, fundamentally disagreed with the entire premise of Oz.

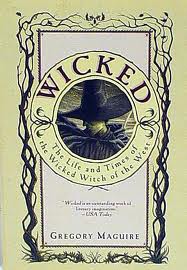

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, and specifically its cover and annoying Reader’s Guide, is marketed as a response to the 1939 film. Certainly, its initial popularity may well have come (or been helped by) the popularity of the 1939 film, and Gregory Maguire’s physical description of the Wicked Witch of the West owes a considerable amount to Margaret Hamilton’s green-skinned portrayal in that film. But although references to the film appear here and there, Wicked is a response to the entire Baum canon, and to a lesser extent, fairytales in general. At heart, it questions Baum’s statement that most bad people are bad because they do not try to be good.

What happens, asks Maguire, when people trying to be good live in a world that is, fundamentally, not good? In an Oz filled not with abundant food, wealth, and adventure, but teeming with vicious politics, murder, sex and—perhaps most surprisingly—religion?

As befits the title, Wicked is primarily the story of Elphaba, the Wicked Witch of the West. (Her name was coined from L. Frank Baum’s initials; in the original Baum books, the Witch never had a personal name.) It is also, to a lesser extent, the tale of Glinda the Good, and to an even lesser extent the Wizard of Oz, and, to a great extent, the tale of people unfortunate enough to live in a land of magic without complete understanding, control, or belief in magic. As befits a revisionist history, the Elphaba we first meet is an innocent if rather green and biting child with a fondness for the word “horrors.” When we next meet her, she is a somewhat cynical, occasionally sharp tongued teenager with a strong moral core. A series of tragedies, betrayals, conspiracies and a murder transforms her into a still moralistic terrorist.

Wicked was written before 9-11, but terrorism, its moral implications and consequences, and the vicious response of state leaders to it, still permeates the second half of the book, and Maguire does not shy away from focusing on the tragedies terrorism creates—however justified the terrorists may feel. Elphaba is convinced—and the novel agrees with her—that the political structure of the Wizard of Oz she battles is unjust and cruel. The Wizard’s shock troops, called the Gale Force, strongly resemble Hitler’s SS, in an evocation I assume is deliberate. The Wizard is systematically rounding up sentient animals and depriving them of their rights; in a generation, these Animals transform from members of the community, scholars and skilled laborers, to persecuted and often slaughtered animal beings, some retreating to utter silence.

Against this, Elphaba’s decision to fight the Wizard with violence makes moral sense—and even caught in a moral tempest, as she is, she shies away from killing children as byproducts of her mission. But this decision does not save her, and her actions begin begin her slow and steady course into guilt and obsession.

The book asks, often, about choices, suggesting both that Elphaba has no choice, doomed as she was from birth, as a child of two worlds without being part of either, by her rather awful, self-centered parents, models of lousy parenting, and by her green skin, marking her immediately as different and odd. None of this prevents Elphaba from attempting to earn a university education. On the other hand, her choices, and the guilt that weighs her later, are largely guided by things that have happened to her both in her years dragged around the swamps of the Quadling Country and at the university—which she is attending in part because of an accident of birth, which made her a member of one of the noble families of Oz. (Incidentally, the suggested abundance of these makes me think that Maguire also read the Thompson books, although those are not referenced directly in the text.) Elphaba herself questions how much choice she has had; then again, perhaps it is easier for her to think of herself as doomed by destiny.

Intriguingly enough, even as he rejects Baum’s concepts, Maguire does an admirable job of explaining away the multiple inconsistencies in the Baum books—particularly in explaining how people can eat meat in a land where animals talk, teach and attend dinner parties, and in explaining the varied and completely contradictory histories of Oz. (As I’ve noted, these inconsistencies never bothered me much as a kid, and I expect that they can be waved away by “magic,” but they clearly at least nagged at Maguire.) In Maguire’s Oz, some Animals can talk, and some animals cannot, and the conflicting histories of Oz are woven into its religious practices and propaganda. This absolutely works for me.

As do the religious conflicts among unionists and Lurlinists and non-believers, and the religious obsession of many characters. Too often in fantasy religion is either distant, or too close, with gods interacting directly with characters, and characters in turn becoming far too aware of just how this fantasy universe operates, at least divinely. Here, characters cling to faith—in at least two cases, far too fiercely for their own good—without proof, allowing faith or the lack thereof to guide their actions. It allows for both atheism and fanaticism, with convincing depictions of both, odd though this seems for Oz. (Baum’s Oz had one brief reference to a church, and one Thompson book suggests that Ozites may be at least familiar with religious figures, but otherwise, Oz had been entirely secular, if filled with people with supernatural, or faked supernatural, powers and immortality.)

Some suggestions make me uncomfortable, notably the idea that Elphaba is green and Nessarose disabled because of their mother’s infidelity. A common theme in folklore, certainly, and for all I know actually true in fairylands, but I am still uncomfortable with the concept that infidelity would damage children physically, even if perhaps this should or could be read as a physical manifestation of the emotional damage that children can suffer from fractured marriages.

And I’m equally uncomfortable with the idea that children of two worlds, like Elphaba, cannot find happiness in one of these worlds. (She is never given the choice of the other world, and hardly seems to accept her connection to that world, and even its existence.) This, despite the suggestion at the end of the book that Elphaba’s story is not over, and perhaps—perhaps—she has a chance one day.

References to Baum’s other books, both Oz and otherwise, are scattered throughout the text, and in a small inside joke, the missing Ozma is Ozma Tipperarius. I liked the sprinkling of tik-toks throughout, and the playful suggestion on the map that if you travel just far enough you will find a dragon – perhaps the original time dragon, perhaps another dragon. I was also amused that, as befits a revisionist history, the wild Gillikin Country of Baum’s Oz has been turned into the most civilized land of Maguire’s Oz, and the highly settled, peaceful Winkie Country transformed into the wildly dangerous lands of the Vinkus. The book also bristles with references to other myths and fairytales, suggesting that just perhaps Oz is a land where myths have gone terribly, terribly wrong, caught in clockwork and machinery. As one talking Cow notes mournfully, that is enough to cast many things—including the wonder of talking animals—aside.

One word of warning: the book does get a bit bogged down in its third quarter, when Maguire seems to be wondering precisely how to get Elphaba over to the West and transform her into the green rider of broomsticks known from the film. It rouses back sharply in the last quarter, though, and had me looking forward to the two sequels (which I still haven’t read, but will be trying to get to over the holiday season.)

I cannot love this book—it is too emotionally cold, too harsh. But I can admire it, and I can become utterly absorbed by it, and enjoy the many quotable bits. And I can be heartbroken when Oz cannot, in the end, welcome everyone—even those who should, by rights, be part of it.

Before you ask, Mari Ness has not gotten around to seeing the musical, although that will be changing very soon. She lives in central Florida.

I found the first of the sequels–I never read the other–much bleaker and more depressing than Wicked itself, which is something of an accomplishment. Overall, a grand book, this one, but I’m glad they lightened it up for the musical; there’s only so much soul-crushing despair a person can take with song and dance numbers.

For Elphaba’s condition (and her sister’s), I thought it was all but explicit that they were the result of her mother drinking the patent medicine the traveling quack was selling in his pre-Wizard-of-Oz days; some combination of fetal alcohol syndrome, magic, and god only knows what was in those bottles.

Tried to read this and found it an abomination. I can not imagine why anyone would think it worthy of a musical adaption.

I enjoyed Wicked, though it was somewhat sharp inside my head – a little too cynical, a little too bleak. The two sequels (well, one and a half sequel; I never finished the second one) are even sharper and more despairing, so keep that in mind.

When I found out there was a musical (and that my marvelous partner had gotten tickets for us), I immediately went online to look up the libretto, because honestly, the book starts with sex and ends with death, and I had to see how the musical dealt with that. The musical is delightful, and I’ll say nothing more about that, so as to avoid spoiling too much.

I don’t regret reading Wicked, which I came to after Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister. I do regret the time spent on Son of Witch, and on Lion Among Men (I think that’s the third one’s title).

Just finished reading Wicked last weekend. I enjoyed it, but it’s such a downer that I’m in no hurry to read the sequels. But do please review the musical when you get a chance to see it, I’m really curious.

I loved Wicked, but I found the sequels, A Lion Among Men especially, to try too hard to break free of Baum by burying everything ankle-deep in either sex or politics – and if you weren’t paying close attention to the latter in Wicked, much of A Lion Among Men will appear incoherent.

I enjoyed this article. :) When I read Wicked, I hadn’t (and still have not) read any of the books or seen any of the films (in full) associated with Oz. In large part, that may have gone into how much I enjoyed the book, but I really appreciate your insight into the world here.

Of the two sequels, I enjoyed the third, A Lion Among Men, best. If you review that one here for Tor, I would love to read it. :)

I once described the musical as a High School AU of the book, since it seems to have little in common but the names and some of the plot.

I thoroughly enjoyed this spin on Baum’s world, and enjoyed the musical even more, as it is much, much, much less depressing (as others have noted). The sequels fell off a cliff, I read Son of a Witch because I bought the damn thing, no other reason to finish that book. Went nowhere, taught nothing, useless, although I’ll be interested in your own torture as you read it to see if I just plain missed something. No interest in picking up a third in that storyline.

Haven’t been able to get into the other books of his either, think the spell was broken after that initial read.

Enjoy the holidays, for sweet Lurline’s sake please don’t read the rest of this junk over the holidays! Save it for bleak midwinter…

What a thoughtful blog! Thanks, Mari!

Thanks for the review! I never did get around to finishing this…

I heard the musical soundtrack ages ago(back in high school!) and absolutely loved it(along with most of my friends!). Then about a year ago, saw the book at Target and so started reading it…probably spent a few hours there reading. Oops. Anyway, I did find it a bit too depressing for me…only got about 1/3 of the way in before I decided it was not for me. So, thanks for the thoughts and mini-review to lessen my ignorance a bit!

This is an excellent review and encapsulates the tension of the book very well. I personally found all the background and worldbuilding significantly more interesting than the plot, and never quite finished the book (all but the last 40 pages or so).

Again, excellent and thoughtful review. Well done.

@fadeaccompli The book occasionally questions whether it was the patent medicine or Melena’s sleeping around that caused the problems — especially after the book reveals who Elphaba’s father is (I’m trying to be cautious with spoilers here, especially since I don’t know if that comes up in the musical or not). The implication is fairly strong that her, um, unusual parentage is part of the cause. Nanny is the main character to espouse the “infidelity did it” view, but other characters mention this as a possibility as well. My guess is that you are correct, and the actual cause was the Wizard’s patent medications, but the alternative suggestion as made by others made me uncomfortable.

@tudzax1 – I haven’t seen the musical yet, but I’ve been told by several people that it’s very different from the novel. My guess is that someone thought, hey, a musical version of Oz told from the Witch’s point of view! Look how much money the MGM film made! Yay!

@arianrose “Delightful” is a cheery word. Thanks — I’m heading to the musical with a couple of friends, one of whom is not overly fond of angst, so I’m glad to hear we might not destroy him. (But they have booze in the bar at the theatre, so, we should be good.)

@bellman – I’m curious about the musical as well, especially since it had a habit of only showing up in my vicinity when I was either too broke or too busy or both. Hopefully my curiosity will be assuaged in March.

@Malebolge — I was so taken aback by the mere concept of politics in Oz that I did pay attention, so hopefully that will stay in my head when I get to that book in a couple of weeks.

@brownjawa – You know, it’s really odd the way the readership of this book does not match the readership/viewership of the Oz book and movie? I’ve lost track of the number of people who, like you, read this book but never read the original Baum books and saw the movie either years back or not at all.

I find this odd because I would have thought this book would only intrigue Oz fans, but clearly not. It’s good to know that the book is that accessible to those who never read the original Baum books. But know that you are not, based on an unscientific sampling of people I’ve talked to, alone.

@AnnaP – Also reassuring! It seems I won’t have to drink as much after seeing the musical as I thought I might!

@FalalalaalalElphaba – Well, some might argue that the holidays are the bleak midwinter…

…more seriously the next set of books that I’ll be reviewing have a more cheerier tone which we all need for January.

@Sonofthunder – It’s definitely a bleak book, and I can’t blame anyone for not finishing it — especially given the bogged down third quarter of the book, where I admit I found it a bit of a slog. If it hadn’t remarkably improved at the end I might not recommend it to anyone — or I’d recommend stopping after the Emerald City chapter.

@George Tucker – Thanks!

I think the last 40 pages are actually quite good and got me back into the book again — I liked Maguire’s take on Dorothy. But, yeah, I thought the plot dragged in the third quarter.

I read Wicked after being introduced to the soundtrack to the musical version. There are definitely good parts to the book, but the one thing I could not stand was Maguire’s insistence on hitting you over the head with a bat for all his morals/lessons. It felt like they had the exact same discussion about the nature of evil (born that way or became that way) every other chapter, though it was probably only 3 or 4 times in the whole book. I hate having things shoved down my throat, and that tendancy is the main reason I never read any of the other books.

I prefer the musical to the book because it doesn’t force things down your throat. Plus, it’s great music. You should see the show for the act 1 finale alone; I’ve seen it 4 times and I still get goosebumps.

I may be alone in the world in preferring Son of a Witch to the two (so far) other books in the Wicked Years series. I found Liir very sympathetic.

I thought the stage version was a concise and enjoyable distillation of the book. Although I was revolted by the “origins” of the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman–those’re not in the book, thank heavens.

As far as RPT homage goes, I’d assumed that the elephant woman in the Wicked books was Maguire’s extrapolation of Kabumpo.

Thank you once again for your insight and review.

I was just wondering a couple days ago if you would be reviewing “wicked” soon and here you have, hooray!

This is one of the more thoughtful reviews/analyses of Wicked that I’ve run across. As a longtime Baum and Oz fan, my reaction to the book ultimately parallels that of the commenter at #2 — when I finished the novel, which I finally sat down and read when a book group I was in picked it, I very carefully threw the book across the room just so I could say I’d done so. (I then promptly sold the book back to Powell’s once the book group meeting had ended.) At the same time, though, I recognize the level of craft at work in the book and I can respect it on that level.

Where I disagree with the review — and unfortunately, it’s been too long since I read the book for me to cite chapter and verse — is that I am convinced (at least till someone produces direct evidence stating otherwise) that it is neither a deliberate response to anything in Baum, nor written by someone with a deep knowledge of the Ozian canon. What it read like to me at the time was, in a word “anti-fanfic” — a complete original novel with Ozian serial numbers filed onto it. It seemed to me that Maguire had written an original novel, and had then in Dr. Frankenstein fashion attached the Ozian elements in order to sell the darned thing.

Having said that, I’ll add that I too have never seen the musical, but that my impression thereof is that it’s at least as much a Baum adaptation as it is a Maguire adaptation.

i absolutely loved this book. perhaps because it was the first oz book i had read. but i know somethings of oz in the general sense. but i loved this book. and loved this review. :)

I read this because I had tickets to the musical. Before that I had read “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” as a kid and seen the movie…more times than I can say. Let’s say every year when it comes on, plus some of the sequel movies. “Wicked” was fascinating start to finish. It was probably the world-building of Oz and the crafty nods to the film that had me (ticktockery, Elphaba’s song). But in the end I thought the portrait of Elphaba as this ‘rise and fall of an idealist’ was pretty compelling. It has become one of my favorite books. One thing I noted is that the movie shows the Witch and all her guards as green people. In this book the only green person in the entire nation is Elphaba.

By comparison, the musical was a fascinating adaptation. I slept through a good deal of it, but I thought the tone and style were inspired and the ending of the first act was pretty great.

“Son of a Witch” I loved even more than “Wicked.” Liir’s adventures also lead you on this fascinating study of this odd landscape. “A Lion Among Men” was not at all likeable to me. There’s a character who makes you wonder if his circumstances are dumbluck or bad choices. I did not come away from that thinking well of that character. If anything, I’d like Maguire to give us the Wizard’s story. What does “No Irish Need Apply” have to do with him coming to Oz? How does an outworlder takeover? What was the Grimmerie to him and how was he going to use it back home?

The musical is delightful, with one of the best scores I’ve heard in years. It’s almost impossible to keep from hearing some of the songs in your head for days afterward.

I’d advise buying the CD with the original Broadway cast, since that features two of the best singers in musical theater.

I tried reading it. Found it depressing and distateful and didn’t finish it. I read all the Oz books when I was a kid. Oz was quirky and fun and joyous.

I have always seen Wicked the book as being a reimagining of the books, and the musical as a reimagining of the movie. Both are god but for different reasons.

@Rowanmdm – Huh. Interesting. I didn’t feel as knocked over the head by the moral discussions, although you are certainly right that they make several — almost continuing — appearances.

I do plan on seeing the show fairly soon — the tickets, I’m assured, are in the mail, thank you slow holiday mail from Ticketmaster.

@eric Shanower – You know, I completely missed the idea of the princess as a homage to the elegant elephant, but you’re right.

@Longtimefan – I’m also reading through the next two books now, so reviews should be coming up eventually.

@John C. Bunnell – I initially disagreed with your analysis of Wicked as anti-fanfic, given the multiple sly references to various things in the Baum canon; now that I’m reading through Son of a Witch, I think you’re onto something, although it’s more true for the later book, so much thanks for this insight.

@tamyrlink – Thanks!

@sofrina – I thought, and I could be wrong, that the “No Irish Need Apply” was either to let us know that yes, the Wizard really did come from the U.S. in the late 19th century, or to possibly let us know that he was forced into his role because he was Irish, and therefore could not find work, forcing him to eventually become a tyrant, in another illustration of the theme of racism/judging by appearances. I thought he was able to take over because the Ozmas had become corrupt and incompetent.

@Gardner Dozois – I’m trying to remain unspoiled for the musical, so I’m not planning on buying any CDs until my friends and I go in early March. But once I do, since I’m a massive, massive Kristin Chenowith fan, I will probably be trying to buy whatever CD she’s in :)

@johntheirishmongol – I have to agree that the book is depressing. I didn’t find it distasteful, but I did want to read something fluffy and lighthearted and funny afterwards.

@Drolefille – Huh. Interesting. I’m getting more and more interested in the musical with each comment!

We saw it with Kristin Chenowith on Broadway and she was fantastic; that’s why I recommended the original cast album, since Idina Menzel is also in it and also terrific–the show is to some extent a duet show between two of the best singers in musical theater, which is why you should probably get the original album, no matter how much you like the touring company.

Kristin Chenowith has also popped up on GLEE several times. (As has Idina Menzel, for that matter.)

@MariCats, i think the wizard’s origins and rise to power would be a fascinating story. that he couldn’t find a job in our world is fine, but it’s no mean feat to get to oz from here. he was hunting the grimmerie. for what purpose? what would that have changed in our world? how did he become a soldier and then scale the political ladder? the corruption of the ozmas is too simple. there must be an awful lot more to it than that. after all, the wizard was corrupt too. he threw in the towel and fled hours before he was to be assassinated. plus that repeated march into the ocean against the tide. that has to be one heck of a biography.

@sofrina – I heard some rumors that Robert Downey Jr. is going to be in a movie exploring just that – how did the Wizard end up in Oz? Once there, how did he rise to power? Of course, assuming that movie gets made (and I just checked; IMDB.com doesn’t seem to have it in development) that will all be based on Baum’s books and whatever the screenwriters create, which I assume will be fairly far from both Baum and Maguire’s creations.

Anyway.

But yeah, I agree with you that this would be one heck of a biography. My guess, now that I’ve just finished Son of a Witch, is that we aren’t going to get it from Maguire. Pity.

The Downey Jr.-as-Wizard report is not, or at least not entirely, mere rumor: Deadline.com reported on the story back in June. The two other salient points are that the project is under the Disney umbrella, and that Sam Raimi is set to direct — both of which could be either very good or very bad news, depending on which Disney and which Raimi we get.

As I suggested in the comment thread over there, I think the producers of this contemplated film would be smart to buy the rights to Donald Abbott’s How the Wizard Came to Oz, mostly to avoid any possible legal wrangling down the line, but also because it’s a fairly reasonable (if none too epic) take on the story.

I read this shortly after its publication way back in the 90s, and absolutely loved it. It is indeed a response to Baum and more specifically to the MGM production of The Wizard of Oz. It is, simply, brilliant. There is not much more I can add to the discussion since all of my points are made in the blog post.

I will say this, however, people really hate Wicked… and I understand why; any attempt to “mess” with a childhood love inevitably provokes this reaction. Personally, I prefer what Maguire has done with Oz than what MGM did with it.

in the end, i don’t think the book succeeded very well. i believe it started strongly, and has great language, but it never quite knows exactly what it is. it’s been almost a year since i read it, so it’s not fresh in my mind, but i remember feeling disjointed as the book progressed. maybe that’s the intention, but i feel like the end doesn’t live up to the promise of the beginning. as this blog post pointed out, it seems to crumble under the weight of having to tie everything together

dr

http://entropy2.com/

I agree with you. The book is very well written for the most part and I enjoyed it at times, but I do not love it.

It is a depressing, hateful story that ruins Oz in more ways than it fixes it.

The sequels are far worse though, and A Lion among Men was almost unreadable in my opinion.

Out of Oz is the best next to Wicked but in the end resolves nothing and left me with so many questions!!

Gregory Macguire is a talented author though, and I will continue buying any sequels he makes.

Maybe one day he will write a canon style Oz book. :)

I wrote a take on Wicked back in 2006:

http://dareiread.blogspot.com/2006/01/wicked.html

I might add that what I found most problematic about Maguire’s plot was where it had to mesh most closely with Baum’s original novel. Baum’s classic fairytale repetitions remain at odds with Maguire’s modern psychological explorations. It felt like Elphaba was doing what Baum had the Wicked Witch doing not because she wanted to but because she got magically trapped in a foreign plot.

Their mothers infidelity wasn’t what caused Nessarose to be disabled, though, it was the pills that Nanny gave her mother, at least that is the very heavy implication. I do agree with you about the 3rd quarter, he was trying really hard to get Elphaba to Kiamo Ko and gain the broom, flying monkeys, etc., and I honestly didn’t buy it. And the last part just depressed me, a lot more than the stuff before it.

I have read many reviews of Wicked, and I find them all to be describing a book I feel I haven’t read! Wicked, in my experience, has been an honest, uplifting, heart-wrenching, throught-provoking, borderline biblical text. The lessons I have learned and the truths I have come to because of this book feel profound. Perhaps this is because I read it at such a young age and kept re-reading until now, and it has been a constant anchor in my most confusing teenage years, but even still, this book means more to me than any review has expressed. I suppose there is the fact that I am not a professional critic, I am an emotionally invested reader. But even knowing that, I am always surprised that this book is not automatically touching, transformative, and amazing to everyone who reads it. And, of course, this is not commentary at all on this review. I found this review to be accurate and objective. It just seems that objectivity would be impossible in the light of a book that changed my life.

I remember when Wicked the play first came out and I was thrilled to see it – but never did. Fast forwarding to 2017, I happened upon Wicked in a used book store and was thrilled. So reading the novel (also its sequel, Son of a Witch, I must say that I love Maguire’s style of writing, his storytelling – but yes, the story is kind of depressing, my heart goes out to Elfie and all that she had to endure, only to end up a semi-psychotic old crank and then killed – supposedly. Actually I believe that Elphie is faking her death to disengage from the world and its trials. I really hate how Frex cannot lovingly embrace his devoted daughter simply because she is green and then be so blatant about favoring Nessarose – how crass, and there are really people who are that exact same way – I hate that.

It’s 2020 and having just completed Wicked for the first time, I was pleased to find and read your critique.

Spoiler alert.

Regarding the idea that Elphaba and Nessarose had their impediments due to their Mother’s infidelity, I disagree. Though that was a notion mentioned by characters in the book due to feelings of guilt or superstitions, I concluded that the impediments the girls were born with were due to the drugs taken. The green elixir that the wizardly rapist gave the Mother would seem to have affected Elphaba’s pigmentation at conception. And the concoction Mother took early in her pregnancy with Nessarose- to prevent greenness- seems to have caused the birth defect she had.

my way of summarizing Wicked (which I read in 2007, so it’s a very old take) is that The Wizard of Oz is the history written by the victors, and Wicked is the history written by those who were defeated. i recall loving Wicked at the time, but haven’t attempted the sequels, and after reading all the comments, i remain undecided.