The most interesting and perhaps most overlooked move that David Gerrold makes in his fractal time travel book The Man Who Folded Himself is that he writes the whole story in the second person without alerting you, the reader, directly to this fact. You’re brought inside the book without really knowing it. The second most interesting fact about Gerrold’s 1971 Hugo nominated book is that the book has no protagonist. Instead of a protagonist, the reader is presented with a contradiction and asked—no, compelled—to identify with this empty place in the narrative. And the reader is coerced into position, made to stand in for the narrator and protagonist, with two simple sentences:

“In the box was a belt. And a manuscript.”—David Gerrold, The Man Who Folded Himself, p. 1

For those who haven’t read Gerrold’s book here is an excerpt from the inside of the book jacket for the 2003 BenBella edition:

You slowly unwrap the package. Inside is a belt, a simple black leather belt with a stainless steel plate for a buckle. It has a peculiar feel to it. The leather flexes like an eel, as if it were alive and had an electric backbone running through it. The buckle too; it’s heavier than it looks and has some sort of torque that resists when you try to move it, like the axis of a gyroscope. The buckle swings open and inside is a luminous panel covered with numbers. You’ve discovered a time machine.

You may have heard that the Chinese government recently banned all television programs and films that feature time travel. The Chinese, through the State Administration for Radio, Film & Television, stated that History is a serious subject, far too serious for the State to stand idly by and abide these time travel stories that “casually make up myths, have monstrous and weird plots, use absurd tactics, and even promote feudalism, superstition, fatalism and reincarnation.” Some have said that this banishment indicates that the Chinese State fears the development of alternative histories, and wishes to ward off thoughts of alternative futures. However, if the bureaucrats working for the Chinese State Administration for Radio, Film & Television have read Gerrold’s book then they’re less likely to be concerned that time travel stories present visions of a better past or future, and more likely worried about what time travel reveals about the present. What the Chinese censors don’t want people to know, from this way of thinking, is that our current reality doesn’t make sense.

You may have heard that the Chinese government recently banned all television programs and films that feature time travel. The Chinese, through the State Administration for Radio, Film & Television, stated that History is a serious subject, far too serious for the State to stand idly by and abide these time travel stories that “casually make up myths, have monstrous and weird plots, use absurd tactics, and even promote feudalism, superstition, fatalism and reincarnation.” Some have said that this banishment indicates that the Chinese State fears the development of alternative histories, and wishes to ward off thoughts of alternative futures. However, if the bureaucrats working for the Chinese State Administration for Radio, Film & Television have read Gerrold’s book then they’re less likely to be concerned that time travel stories present visions of a better past or future, and more likely worried about what time travel reveals about the present. What the Chinese censors don’t want people to know, from this way of thinking, is that our current reality doesn’t make sense.

Consider what the philosophy professor Geoffrey Klempner wrote about The Man Who Folded Himself:

“The basic ground rule for writing any piece of fiction is that the story should add up. The plot should make logical sense. The question we have to ask is: Is the story about the time belt on the bedside table consistent? Or, more precisely: Is there a way to interpret what happened that gives the story the required coherence?”—Geoffrey Klempner, Afterword for The Man Who Folded Himself, p. 122

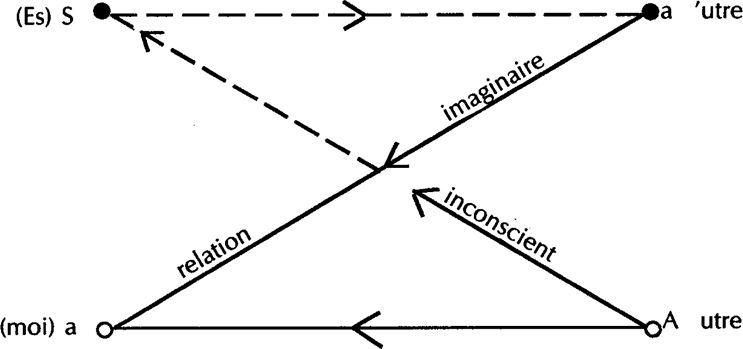

Klempner points out that every time the time traveler in the story goes back in time to meet a younger version of himself, he either sets up a paradox or enters an alternative reality. After all, if the protagonist goes back in time to tell himself what horse to bet on, he’ll be going back to a time where he already knows he was not. After all, if he’d been there to tell himself to bet on the right horse then he’d already be rich and he wouldn’t have to go back in time in order to give himself the name of the horse on which to bet. On the level of plot, Gerrold’s time travel book doesn’t add up to a single story. Rather, to get a story out of the book, the reader has to posit multiple novels and accept that Gerrold’s book consists entirely of the points where these other books meet. This book consists entirely of the interstices of the others.

“I’d been getting strange vibrations from [my older self] all day. I wasn’t sure why. (Or perhaps I hadn’t wanted to admit—) He kept looking at me oddly. His glance kept meeting mine and he seemed to be smiling about some inner secret, but he wouldn’t say what it was ” David Gerrold, The Man who Folded Himself, p. 57

Here’s another question: Why does the I, the you, in Gerrold’s novel fall in love, or lust, with himself/yourself? It may seem an obvious thing, but it is a bit odd. Why or how would a time traveler’s sex act with himself be something more than masturbation? Further, why should the time traveler want something more from himself than masturbation?

Gerrold’s book seems to indicate that the answer resides in the time traveler before he gets the time machine. That is, in order for a time traveler to set off to seduce himself he must already be an object for himself. The seduction is an attempt to overcome an alienation he already feels even before he literally meets himself as an other.

Another way to look at the solution for this story is that rather than an infinite number of alternative universes, there is really none. That is, there is something incoherent about the universe itself.

Another way to look at the solution for this story is that rather than an infinite number of alternative universes, there is really none. That is, there is something incoherent about the universe itself.

“Consider it’s the far future. You’ve almost got utopia—the only thing that keeps every man from realizing all of his dreams are all those other people with all their different dreams. So you start selling time belts—you give them away—pretty soon every man is a king. All the malcontents go off time-jaunting. If you’re one of the malcontents, the only responsibility you need to worry about is policing yourself, not letting schizoid versions run around your timelines,” David Gerrold, The Man Who Folded Himself, p. 75

Perhaps another title, a more accurate title, for Gerrold’s book would have been “The Man Who Discovered a Fold in Himself,” or better still, “The Man Who Came Into Being Because of a Fold in Himself,” or even “The Fold in Time That Took Itself to Be a Man.” Finally, an alternative title might be, “You are a Fold in the Time Space Continuum that Takes Itself to Be Reading a Book.”

The most interesting move in The Man Who Folded Himself comes right at the start. It’s the way Gerrold erases the reader, shows the split in reality by showing you both the time belt and the manuscript, and implying they both belong to you.

Douglas Lain is a fiction writer, a “pop philosopher” for the popular blog Thought Catalog, and the podcaster behind the Diet Soap Podcast. His most recent book, a novella entitled “Wave of Mutilation,” was published by Fantastic Planet Press (an imprint of Eraserhead) in October of 2011, and his first novel, entitled “Billy Moon: 1968” is due out from Tor Books in 2013. You can find him on Facebook and Twitter.

Because of some things that happen in the novel, it was often referred to as The Man Who Fondled Himself

Well, yes. Supposedly, Gerrold’s original title was The Man Who Fucked Himself… which his publisher promptly made him change.

An alternative title for this essay could be “You are a Fold in the Time Space Continuum that Takes Itself to Be Reading an Interpretation of a Book about a Fold in the Time Space Continuum that Takes Itself to Be Reading a Book.”

ahh, I remember this book fondly. One thing I especially liked, though it took me a while to figure it out: yes, the book says “In the box was a belt. And a manuscript”, and the manuscript says “In the box was a belt” without any manuscript (IIRC), and … what follows … follows

I liked this book mostly because it struck every possible thing that might happen with time travel. I also think the OP here missed a major point which was that every time he goes back in time and meets himself, he is really creating a divergent reality. Gerrold meticulously explains this in the book. That’s how he can go back and meet a younger self without remembering it happening when he was younger. With all due respect to the article writer here, Gerrold explained in detail how time travel “really works” in the story and that it is not what people think. He explains how he can meet a younger self and not already remember it happening, how there is no “Grandfather Paradox” or “Butterfly Effect”, etc.

On the other hand, the first time I read the book, it was a library copy. Whoever donated it or someone who read it wrote in the margin after Part One, “You have read the good parts” and warned the reader to stop there before getting to the parts were he had sex with himself.

I think the story was about a guy who totally could not relate to people and sort of lives inside himself but, with time travel, he keeps making copies of himself. In fact, he’s already a copy since “Uncle Jim” was really him too. It’s also a sad story about a man trying to escape his own mortality but he knows he can’t.

I believe Gerrold has since said he wished he had not made the character quite so self-obsessed. I have a copy of the book signed by Gerrold at a convention. Truthfully, meeting him was a disappointment as he was an arrogant jerk. Not that he said anything bad to me but he really is a pompous ass and proved it over and over and I’ve found it is a frequent opinion of him. Since that time, I’ve often wondered how much the character was a reflection of him. Still, the character is basically a character study of “Man against himself”, perhaps the ultimate character study of that type of story.