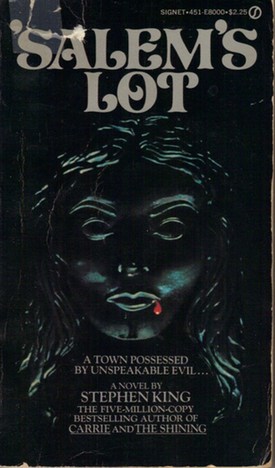

Out of all of Stephen King’s books, the one I read over and over again in high school was ‘Salem’s Lot, and why not: VAMPIRES TAKE OVER AN ENTIRE TOWN! Could there be a more awesome book in the entire world? And it’s not just me. King himself has said that he’s got “a special cold spot in my heart for it,” and without a doubt it’s the bunker buster of the horror genre, a title that came along with the right ambitions at the right time and broke things wide open.

So it came as a surprise to re-read it and realize that it’s just not very good.

The bulk of ‘Salem’s Lot was written before King sold Carrie, back when he was still hunched over a school desk in the laundry closet of his mobile home, dead broke, out of hope, and teaching high school. Inspired in part by a classroom syllabus that had him simultaneously teaching Thornton Wilder’s Our Town and Bram Stoker’s Dracula, he later described the book as, “…a peculiar combination of Peyton Place and Dracula…” or, “vampires in Our Town.” Which is sort of the problem.

After selling Carrie and while waiting for it to be published, King returned to ‘Salem’s Lot (then called Second Coming), polished it up, and sent the manuscript for it and for Roadwork to his editor Bill Thompson, asking him to choose between the two. Thompson felt that Roadwork was the more literary of the pair but that ‘Salem’s Lot (with a few changes) had a better chance of commercial success.

The two major changes he requested: remove a gruesome death by rats scene (“I had them swarming all over him like a writhing, furry carpet, biting and chewing, and when he tries to scream a warning to his companions upstairs, one of them scurries into his open mouth and squirms as it gnaws out his tongue,” King later wrote) and to draw out the beginning and make the source of the evil plaguing the small town more ambiguous. King protested that everyone would know it was vampires from the very first chapter and readers would resent the coy, literary striptease. His fans (and he did already have fans of his short fiction) wanted to get right down to business. Thompson pointed out that when King said “everyone” he meant a tiny genre readership. He was writing for a mainstream audience now, Thompson reassured him, the last thing they would be expecting was vampires.

The two major changes he requested: remove a gruesome death by rats scene (“I had them swarming all over him like a writhing, furry carpet, biting and chewing, and when he tries to scream a warning to his companions upstairs, one of them scurries into his open mouth and squirms as it gnaws out his tongue,” King later wrote) and to draw out the beginning and make the source of the evil plaguing the small town more ambiguous. King protested that everyone would know it was vampires from the very first chapter and readers would resent the coy, literary striptease. His fans (and he did already have fans of his short fiction) wanted to get right down to business. Thompson pointed out that when King said “everyone” he meant a tiny genre readership. He was writing for a mainstream audience now, Thompson reassured him, the last thing they would be expecting was vampires.

And he was right. At the time, nobody expected vampires in a posh, hardcover bestseller. But nowadays, thanks to its success, ‘Salem’s Lot is synonymous with vampires and this drawn-out beginning feels interminable. One could say it’s establishing the characters, if they weren’t some of the flattest characters ever put on paper.

Ben Mears (whom King pictured as Ben Gazzara), comes to the small town of ‘Salem’s Lot (population 289) to write a book about the evil old Marsten House that sits up on a hill and broods like a gothic hero. The Marsten House will have absolutely nothing to do with anything else in the book but it’s great atmosphere and King expends a lot of words on it. Ben sparks a romance with the extremely boring Susan Norton, who helps him overcome the tragic motorcycle accident in his past. Also on hand are an alcoholic Roman Catholic priest who’s questioning his faith, a handsome young doctor who believes in science, and a quippy bachelor school teacher who’s beloved by his students.

For no particularly good reason, Barlow, an evil vampire complete with European mannerisms and hypno-wheel eyes, and Straker, his human minion, also arrive in ‘Salem’s Lot and move into the evil old Marsten House because…it’s cheap? It has a nice view? They want to turn it into a B&B? We’re never quite sure what draws them to the Lot but by the time the book is over, they’ve sucked the blood of most of the townspeople and turned them into vampires, the survivors have fled, and cue the cheap metaphors for economic devastation and the destruction of small town American life.

‘Salem’s Lot is compulsively readable, the high concept hook snags you right through the lip and reels you in, it’s full of high-five-worthy action scenes, the bad guys are so very, very arrogant that it’s a pleasure to see the smirks wiped right off their faces, and King kills his good guys like it’s going out of style. There are still some clumsy sentences (“An expression of startlement” crosses someone’s face) and characters repeatedly “almost” burst into laughter at inappropriate moments (they also laugh “fearfully,” “queasily,” “evilly” and “nervously” – 31 flavors of adverb-inflected laughter). But the real reason ‘Salem’s Lot isn’t very good is because it was the book where King was trying really, really hard to reach beyond the Weird Tales audience and the stretch marks show.

‘Salem’s Lot is compulsively readable, the high concept hook snags you right through the lip and reels you in, it’s full of high-five-worthy action scenes, the bad guys are so very, very arrogant that it’s a pleasure to see the smirks wiped right off their faces, and King kills his good guys like it’s going out of style. There are still some clumsy sentences (“An expression of startlement” crosses someone’s face) and characters repeatedly “almost” burst into laughter at inappropriate moments (they also laugh “fearfully,” “queasily,” “evilly” and “nervously” – 31 flavors of adverb-inflected laughter). But the real reason ‘Salem’s Lot isn’t very good is because it was the book where King was trying really, really hard to reach beyond the Weird Tales audience and the stretch marks show.

Heavily influenced by Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Grace Metalious’s blockbuster small town scandal novel, Peyton Place, and Shirley Jackson’s great American horror novel, The Haunting of Hill House, ‘Salem’s Lot never transcends its influences. It either superimposes Dracula onto a modern-day American setting, or it drops some vampires into Peyton Place and while there’s a certain frission to the juxtaposition, its characters are super-model thin, it strains for importance harder than a constipated Elvis, and King’s imitation of Peyton Place is about as deep as a mud puddle.

Metalious’s novel was an exposé of the secret scandals in small town New England, a “let’s rip off the scabs and let it all bleed” potboiler that sold a bazillion copies. It’s full of abortions, unmarried sex, knuckle-dragging working class types who lock themselves in basements and drink cider until they get the DTs, hypocritical religious cults, and babies born out of wedlock. But it’s also anchored by several complex and well-drawn characters and Metalious’s ability to convincingly write about the joys of small town living as well as its seamier side.

‘Salem’s Lot has no joy and its inhabitants are drawn with crayons. The town is a hillbilly hellhole from the very first page. The heroes are just-add-water, one-dimensional Square-Jawed Champs or Mighty Men with Feet of Clay right out of Central Casting, while the secondary characters who populate the Lot are overheated Peyton Place pastiches. In King’s book, everyone is hiding a terrible secret and the town is populated exclusively by baby-punchers, malicious gossips, secret drinkers, child-hating school bus drivers, porn-loving town selectmen, women’s-clothing-wearing hardware store owners, secret murderers, and pedophile priests. Everyone is either a moron, a bully, or a tramp, and all of them are bitter, sour, and hateful. Even the milkman turns out to secretly hate milk.

‘Salem’s Lot has no joy and its inhabitants are drawn with crayons. The town is a hillbilly hellhole from the very first page. The heroes are just-add-water, one-dimensional Square-Jawed Champs or Mighty Men with Feet of Clay right out of Central Casting, while the secondary characters who populate the Lot are overheated Peyton Place pastiches. In King’s book, everyone is hiding a terrible secret and the town is populated exclusively by baby-punchers, malicious gossips, secret drinkers, child-hating school bus drivers, porn-loving town selectmen, women’s-clothing-wearing hardware store owners, secret murderers, and pedophile priests. Everyone is either a moron, a bully, or a tramp, and all of them are bitter, sour, and hateful. Even the milkman turns out to secretly hate milk.

King’s heartlessness towards his one dimensional characters gives him the freedom to kill them off with great panache (their deaths are their most interesting qualities), but he also makes the adolescent mistake of assuming that depicting hammy scenes of wife-beating, baby-battering, cheating spouses, abusive husbands, and drunk bullies is somehow writing a mature and adult book. Instead it’s a self-indulgent wallow in dark n’gritty cliches, like an angry adolescent who has just discovered R-rated movies Telling It Like It Is, Man. The result is one-note and tedious.

It’s revealing that the only memorable character in the book is the only new one King bothers to add to his mix: Mark Petrie, an overweight horror nerd whose lifetime of pop culture consumption has been a bootcamp for the vampire apocalypse. The second the vampires parachute into town he’s ready to rock and roll, prepped for action by a lifetime spent consuming horror movies, EC comics, and pulp fiction. Mark is the prototype for the new wave of hero nerds, people like Jesse Eisenberg’s Columbus in Zombieland and Fran Kranz’s stoner, Marty, in Cabin in the Woods. For these guys, being a geek doesn’t make them outcasts, it makes them survivors.

But it’s King’s love of The Haunting of Hill House that really does him in, both for better and for worse. Shirley Jackson was a supreme stylist, and even today Hill House is an unequaled accomplishment; except for Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves no haunted house novel is even within shouting distance. In King’s non-fiction study of horror, Danse Macabre, he labels Jackson’s book as the ur-novel about “the Bad Place” and devotes an entire chapter to Hill House, writing, “It is neither my purpose nor my place here to discuss my own work, but readers of it will know that I’ve dealt with the archetype of the Bad Place at least twice, once obliquely (in ‘Salem’s Lot) and once directly (in The Shining).” In ‘Salem’s Lot it’s the Marsten House, about which King also writes in Danse Macabre, “It was there but it wasn’t doing much except lending atmosphere.”

But it’s King’s love of The Haunting of Hill House that really does him in, both for better and for worse. Shirley Jackson was a supreme stylist, and even today Hill House is an unequaled accomplishment; except for Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves no haunted house novel is even within shouting distance. In King’s non-fiction study of horror, Danse Macabre, he labels Jackson’s book as the ur-novel about “the Bad Place” and devotes an entire chapter to Hill House, writing, “It is neither my purpose nor my place here to discuss my own work, but readers of it will know that I’ve dealt with the archetype of the Bad Place at least twice, once obliquely (in ‘Salem’s Lot) and once directly (in The Shining).” In ‘Salem’s Lot it’s the Marsten House, about which King also writes in Danse Macabre, “It was there but it wasn’t doing much except lending atmosphere.”

And that puts a finger directly on the problem. After the lean, mean, speed machine that was Carrie, ‘Salem’s Lot gets bogged down in endless passages of purple prose that aspire to Jacksonian greatness but really just sound like endless passages of purple prose. Shotgunning words insures that he occasionally hits the target in these sections with lines about “the soft suck of gravity” that holds people to their hometowns, but more often than not we get dust motes dancing in the “dark and tideless channels of their noses.” His soaring word poetry is all Shirley Jackson hand-me-downs, with a little bit of Ray Bradbury masking tape holding it together.

But these purple passages are important, because they indicate that while King’s ambitions outstripped his abilities, at least he had those ambitions in the first place. When ‘Salem’s Lot was published there wasn’t a field less given to literary claims than horror. It was where you went if you purposefully wanted to reject literature. William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist wasn’t famous for being well-written, it was famous for purporting to be true. Rosemary’s Baby was admired not for Ira Levin’s spare style, but for its breakneck narrative. The only widely-read horror novelist with any claim to being a literary stylist was Thomas Tryon, and he was the exception, not the rule. But, as King demonstrates in these purple passages, he wanted to reach higher. He didn’t just want to write gross-out scenes of teenaged bacne, giant green snot bubbles, gushing menstrual blood, pig slaughter, or upthrust bosoms and make a quick buck on the drugstore racks. He wanted to write about people’s lives. He aspired to literature.

Horror didn’t have big ambitions in 1974, but ’Salem’s Lot was a hardcover attempt at a literary novel that also happened to be about vampires eating a small New England town. Often overwrought and eminently skimmable, ‘Salem’s Lot was an indication that Stephen King wasn’t just writing about a couple of people in weird situations, and he wasn’t just writing science fiction or fantasy. He was writing horror, and he was writing it with the same ambitions as the best mainstream novelists of the day. The book is a failure but it’s important as a statement of purpose, a manifesto, an outlining of intentions. King’s reach far exceeds his grasp and ‘Salem’s Lot falls way short of his lofty target, but he would hit these marks in his next book. Because if there’s a keeper out of the entire King canon, it’s The Shining.

Grady Hendrix has written about pop culture for rags ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today. He also writes books! You can follow every little move he makes over at his blog.

I have no interest in defending King, but I must take issue with the glib (or, possibly, uninformed) statement that “Horror didn’t have big ambitions in 1974.”

The early ’70s saw the publication of Ramsey Campbell’s DEMONS BY DAYLIGHT and the early work of T.E.D. Klein.

It seems like Hendrix wants to salvage SOMETHING positive to say about SALEM’S LOT by making a hasty, negative generalization of the entire early-’70s horror field and saying that — in that context — King isn’t so bad.

Let’s not let King off the hook that easily.

I’m going to have to disagree with this to some extent. I suppose I didn’t read this when it was released, but having just read ‘Salem’s Lot, I was pretty impressed with the plot, although I agree that many of the characters are flat and pretty archetypal. I thought the book was fun, creepy, and a clever concept though. I guess I haven’t read enough of King to compare it to his other work very well, but I certainly enjoyed my reading.

I came to King kind of late – in my 20’s, in the 90’s. I read ‘Salem’s Lot after loving The Stand and Carrie, but was immensely bored with this vampire tale, mostly because the characters (particularly Susan Norton) felt so flat and uninteresting. I’d been wondering of late if this was an unfair judgment on my part , because I’d love some of his other stuff. So it’s kind of nice to read this.

That said, the perspective of the time in which it was published is helpful, and adds a new angle I hadn’t considered.

It strikes me after reading this that Petrie is also the prototype for the Frog Brothers from the Lost Boys.

It might be a failure as far as his literary aspirations went, but it scared the bejeezus out of me so it’s successful at least on that score.

I think you missed a large opportunity in this piece to discuss H.P. Lovecraft and his influence on King. You cire Peyton’s Place, Hell House, etc., but Lovecraft’s fingerprints are all over the Marsten Hosue.

Spot on.

I read this before I read the original Dracula, and reading Dracula lowered my estimation of this book quite a lot–and I was only in 6th grade.

I’d add to the remarks about the characterization that while many of his later characters weren’t as thin as these, that doesn’t hold true of the good guys. Even in “The Stand”, the good guys are just never as interesting or real as everyone else.

What struck me about Salem’s Lot is the logical followthrough about a vampire moving to town. The geometric progression that decimates the town.

If you think about vampires as a disease with a very high mortality rate, then the plot is simple. One vampire makes two. Two vampires make four. Four vampires make eight. Etc. Eventually, the town is dead.

Prior to Salem’s Lot, I hadn’t seen any novels where this logic was followed. Vampires existed, but they made few, if any followers.

I still see few vampires as intelligent Ebola viruses, but I liked the idea when King wrote it. (And then there’s the short story I read later about someone driving by the abandoned village of Jerusalem’s Lot.)

First, let me say I am and have been a fan of Stephen King since I read The Shining in middle school, and have ready probably half of his work since then, some of it repeatedly. So when I say I disagree with this review, it is due in part because I am biased. But it is also due in part to one or two gross inaccuracies that give the impression that Grady read the cliff notes or Wikipedia version rather than the book itself to refresh his memory. The particular point that brings this to mind is where Mark Petrie is referred to as an “an overweight horror nerd whose lifetime of pop culture consumption has been a bootcamp for the vampire apocalypse,” when King pretty explicitly described him as tall and skinny for his age, with an unnaturally deep well of calm self-assurance for a person so young, as well as being far more self aware and introspective than his peers. Sure, there are many times it is implied that he grooves on the horrow genre, but no more than any other kid in the 70s or any other decade would.

Second, I do agree that many of the characters are flat, but this was purposefully an inversion of Dracula, and having literally just read both in the past month, I can say that King kept his character development about as light as Stoker did with his cast. And just as ‘Salem’s Lot takes quite a while to set the stage before making it clear that vampires are afoot, so does Stoker. The main difference, as King himself states in his own critique of the book, is that in ‘Salem’s Lot, all of the things that worked to help the heros of Dracula in the 1890s actually work against the protaganists in Lot set in the 1970s.

Third, I would think a lot could be forgiven due to both King’s youth and inexperience when this was written, as well as general sophistication of the wider audiance he was aiming for with this book. And as was pointed out in the review, some of the changes for the worse were made at editorial behest, not a particular design of the author.

The last thing I would say is that sometimes, and more often than not with King’s work, a story is just meant to be a story, and if it speaks to you on a deeper level, it almost always entirely by chance.

What KMK said. The Lovecraft influence isn’t as obvious as it would be in some later works, but it’s definitely there.

Also, no offense, but you’re just plain wrong about the character of Mark Petrie. He’s not overweight and he’s not a nerd. He’s a smallish but perfectly fit ten-year-old boy who happens to be bright, well-read, and unusually self-possessed. Mark’s very first scene has him standing up to a bully — and beating him in a fight. (He wins because he’s fearless and a clear thinker.) And he’s quick to understand the menace of the vampires not because he’s into horror comics, but because a vampire shows up outside his window and tries to get into his room. The only thing that’s remotely nerdish about him is that he’s read some old EC comics and he has the Aurora horror-movie model sets. But these things are not, repeat not, central to his character; they’re incidental details that just happen to save him, once.

Also, while I agree that King goes over the top with the Peyton Place stuff, I think you’re going nearly as far overboard in condemning him. There are a number of characters in the town who are good and likable, or at least neutral — the teacher, the doctor, Susan’s briefly glimpsed father. Most of them end up joining the Fearless Vampire Hunters — which is surely deliberate on King’s part; they are, if you like, the town’s immune system.

And the priest is not either a pedophile. (Geez.) He’s just weak. In fact, that’s a rather nicely done point — the two authority figures, the sheriff and the priest, are both likable and in certain ways appealing characters, but they both have weaknesses that cause them to fail at the crisis — the sheriff is tired and disillusioned and ultimately doesn’t think the town is worth fighting for, and the priest’s faith isn’t quite strong enough. That’s why, in the end, it’s the Fearless Vampire Hunters who have to step up.

Doug M.

This book has it’s moments, but I do agree that it was mostly boring to read. If you have knowledge of the prequel short story, you understand why Barlow comes to ‘Salem’s Lot in the first place. More or less it’s like Derry, a spiritual nexus that attracts baddies because years ago a cult tried to raise a Cthulu-type creature and failed, causing the town to be what it is in the novel.

I also see this as a prototype of what he wanted to write about, strange things happening to ordinary people of small town life.

One funny fact you didn’t mention though. Orginally he wanted it set in NYC but Tabby shot it down because, ‘Dracula would be hit by a taxi as soon as he arrived’, he forgot about it for a few days then it came back and he wondered if it would work in a small town or not.

Gotta gree with alot of other people here that some of the points made in the review make me question how closely the reviewer read the book.

In addition to the Petri and Callahan characterizations, I also take issue with this:

“For no particularly good reason, Barlow, an evil vampire complete with European mannerisms and hypno-wheel eyes, and Straker, his human minion, also arrive in ‘Salem’s Lot”

It was explicitly stated by Barlow that he had been in correspondence with Hubie Marsten who was a black arts worshipper of a Lovecraftian sort (I always liked him to Ivo Shandor from Ghostbusters) and had recommended the ‘lot as a potential feeding ground. Thats backed up by the short story mentioned by someone above where the ‘Lot was the scene of a prior Cthulu type summoning.

Having recently read the book for the first time, it seems to me the reviewer didn’t really read it–or at least, didn’t read it very closely. I agree with the comments above, particularly as regards Mark Petrie.

If you’re picking up Petrie’s reading of some horror and possession of some plastic models, you may be forgetting how mainstream an obsession with trashy horror was at that time. Nerdy kids could almost be identified by having read slightly fewer horror comics or dog-eared passed-round-the-class paperbacks than their more mundane contemporaries, and by having glued together slightly fewer glow-in-the-dark Wolfman figures (offset by more spaceship models? I forget).

It was after the early Seventies that horror subsided again into nerdy obscurity. Or maybe I fell out of touch with the culture of ten-year-olds.

I think this book seems plodding compared to some of his other work, and especially if you read it immediately following the whiz-bang ending of Carrie. That’s sort of unfair, isn’t it? It seems to have encouraged skimming, which leads to the sort of mistakes in the review that people are bringing up. I don’t think it is close to the best that King can produce, but it isn’t as the review seems to paint it.

If the HUMANS are flat and two dimensional, Stephen King has spent his energy turning ‘Salem’s Lot itself into a character, and far more successfully. It’s a nice little town on the surface, but with dark undercurrents that eventually prove its undoing. You might have trouble getting a useable picture of the main characters, but you could darn well make a map of the Lot, with little notes in red, ‘Here be Monsters’.

Glad people are chiming in and I just wanted to say that you guys are right: Mark Petrie is skinny. All my life I’ve pictured him as a chubby kid (which is one of the reasons I liked him) but I went back and re-read some of the book (haven’t read it in about two months) and there he is, described as “slender.” So that’s my memory trumping my reading comprehension.

I do stand by the assertion that he’s a proto-nerd, however, since his large collection of Aurora models are his hallmark toy (the only possessions he has that are described, and he saves his own life with them). Although later he saves his life with a technique he learned in a book about a magician, which is a pretty deep nerd signifier (although nerd meant something different then than it does now).

As for the Lovecraft influence, there doesn’t seem to be anything more than a general influence. King cites Thornton Wilder, Grace Metalious, Shirley Jackson, and Bram Stoker as influences on SALEM’S LOT, but not Lovecraft beyond one sentence in the book, “There have even been whispers that Hubert Marsten kidnapped and sacrificed small children to his infernal gods.” King took that sentence and ran with it when he wrote “Jerusalem’s Lot” for NIGHT SHIFT, but that was later.

And while there is a briefly mentioned correspondence between Barlow and Marsten, it is literally one sentence in the entire book. I feel that if King actually cared much about the “why” he would have given it a little more space since he’s one of literatures great over-explainers.

But keep the comments coming. Right now I have to go re-program my mental image of Mark Petrie that I’ve had since I was a teenager.

I read Salem’s Lot shortly after it was published as a paperback, a copy a friend lent me saying, “You might like this.”

I did, and since then have always thought it one of the scariest books I’ve ever read, not the scariest – that would be Tom Tryon’s Harvest Home – but Salem’s Lot was pretty darn close. After initially reading this post, though, I thought I must have been completely mistaken. Of course, then I read the comments and felt some relief. Thanks everyone else who enjoyed this book as much as I did.

I’m not sure why the question of “why ‘Salem’s Lot and not some other town” is supposed to be important at all, let alone worth mocking the book for. Barlow wanted to go somewhere with people for him to eat, isolated enough to avoid attracting a lot of outside attention. Having an evil haunted house to live in is presumably a plus. King gives you just enough of the Barlow-Straker team dynamic to establish that they’ve been traveling around for some time.

Still don’t know where you got the “pedophile priest” or why you think all the townspeople are uniformly contemptible.

Hey EliBishop and DougM – the priest in question is Rev. John Groggins of the Jerusalem’s Lot Methodiest church. I’m not sure about you, but after reading about his “dreams in which he preaches to the Little Misses’ Thursday Night Bible Class naked and slick, and they ready for him…” I figured that there might be grounds to call him a pedophile.

You’re welcome to enjoy ‘Salem’s Lot, but that doesn’t change the fact that it’s just not a good book. However, a book’s artistic quality isn’t the only factor in its worth. I mean, there are plenty of books I love that aren’t good, and vice versa. But for this re-read I’m trying to be honest in my assessments of King’s books and not letting personal feelings such as “I liked it” or “It’s popular” affect my judgment.

@grady: Isn’t “good” a subjective term though? I read ‘Salem’s Lot every October to get me in the right mood for Halloween, and even though I know the story backward and inside out by now, I still enjoy it and get caught up in the frantic search for Barlowe while the town disintegrates.

You are absolutely right on the Methodist preacher in the book though, good catch.

Perhaps your frustration with ‘endless passages of purple prose’ was because of your deadline to finish all King’s early work as quick as you can.

@19 Thanks for correcting my memory – I’d forgotten about that guy.

(Edited to remove pointless remarks that came out way crankier than I intended. Instead:) Regarding your last paragraph, I really don’t think anyone is asking you to write anything contrary to your own judgment. There are just people here who have different opinions about the book, as is not unusual.

@W: See Grady’s previous statement about not having read it in 2 months.

I’ve only read the Lot once, so I don’t remember much of it, other than I didn’t like it at the time, which was 16 years ago. I might like it better now.

But one thing that interested me, is the overuse of adverbs you pointed out. In “On Writing” King states that one of the best things you can do to improve your writing is kill every adverb you find, and instead describe the characters acting “fearfully” or “angrily”(instead of saying “He yelled angrily” write instead, “He yelled, slamming his hand on the table” which conveys the anger and does a show instead of a tell). That’s a rule that has served him well over the years, and it’s amusing to see where he learned it from.

As far as trying to do horror literature, I have to say that I think he succeeded with Under the Dome, crappy ending and all.

I first read King in high school in the early 1980s, catching up on the first few books then reading them as they came out, starting with Cujo. Salem’s Lot was amazing to me, because it was the first I had seen of the R-rated telling it like it is, man, trope and seemed wise and insightful to me at the time. Also, never having read Metalious or Jackson, the second hand insights into small town life and houses as places that store “bad energy” were a revelation to me. There are moments in the book that I still to this day remember with a chill: the mom trying to feed her dead baby, Mark Petrie’s friend hovering at his window and the idea that a kid can more readily accept weird stuff than an adult with fixed ideas of what is and is not real. Most of all, I remember explaining to one of my friends what made the book so scary: the traditional Dracula stories showed vampires as something that happened in creepy old castles in weird foreign places. Stay away from those and you are safe. But the vampires can just as easily find you and kill you in Salem’s Lot if you are in the McDonald’s with all the fluorescent lights on. And as someone above said, the relentless geometric progression of the vampire takeover is also very logical and thus more frightening. I don’t know how it will hold up if I reread it now, but it was very formative in terms of what I liked to read and what scared the bejesus out of me, and I am still very much affected by that today.

Not sure how I missed this post last week but just found it. I was just getting into horror (and reading novels that weren’t about Irish setters, black stallions, or little brothers that eat turtles) when I read this and was still a young’n, so I was totally, indescribably, enthusiastically, (insert additional adverbs here) happy with the book.

That said, “…that also happened to be about vampires eating a small New England town” is the best thing I’ve read all day today.

I had honestly not thought about the secondary characters and the significance of their all having something to hide on an individual level. Of course, now that it’s pointed out to me, it can’t be denied. It’s the truth. The milkman hates milk and the busdriver hates children! I think I turned a blind eye to it because I read Salem’s Lot quite some time after I had read other books where the pairing of quaint geography and “dark corner evil” had meshed much better than they do here. Needful Things and Wizard and Glass seem to fit under this purview. From that point of view, then, the secondary characters and their existence in a small town would seem like the beginning of a trend that had yet to be perfected (not that it is now, but it’s not as bad as it was in the beginning). I’m not trying to defend this. Those characters in Salem’s Lot are wafer thin, and there’s no denying it. I suppose I’m trying to justify it to myself.

Arriving late to all discussions, I guess. This is the last Stephen King book I read, around ten years ago, because we all know that it was fifteen when we enjoyed his books more. And I loved it because of that, because at that time I knew his tricks and knew what the story was about, and even then I loved it: it’s a revenge story of Stephen King against the main characters with his usual theme: when a town is doomed by the Evil, it becomes not worse than it was before. Really: people becoming vampires are not much more evil than the way they were before. It’s a bit like what Thomas M. Disch did in “The Genocides”: you can feel the anger against the characters that the author tries to understand, but somehow the book is telling you that they deserve it. This theme, of course, would be present in many more of his stories and novels, though I think that the definitive one is the tv miniseries “The Storm of the Century”.

I, too, am a little late, but I first read “Salem’s Lot” in high school around 1984 and I thought it was great, but after listening to it on audiobook recently I found the actions taken by the characters were simply too unrealalistic, and all the characters, except for maybe Father Callahan were pretty flat. Firstly, the four adults involving eleven-year-old Mark Petrie in their hunt to find Barlow instead of getting Mark and his parents to leave town to safety. They even say they may all die, but they still involve a little kid. Secondly, the whole McDougall Family segments were useless. Besides to simply introduce a vampire infant that is never descibed in any detail, or as an inside joke because Stephen King and his family were living just like the poor McDougalls when he wrote that book, who knows why they’re in there.

Another thing is King makes Maine look likes it full of country bumpkin-hillbilly types. I never got why King is Maine’s favorite son. He doesn’t make the people look good. He makes the seasons and atmosphere look good, but the people are all rotten.

Interesting review, even though I don’t agree with it. I’ve just finished rereading the book for the first time since the eighties before I do a piece for my own blog — http://www.charleybrady.com — and was surprised by how purely enjoyable it really is. Even at a time when vampires are everywhere to a ridiculous degree, King still manages to make them seem like a virus run rampant.

I think that the errors with Mark Petrie are well covered, so I’ll just add that in the seventies I was one of those kids who also had the entire collection of Aurora models. (And it didn’t make me grow up to be weird, heh heh.) The description of the Frankenstein monster lumbering past the plastic gravestone brought back some memories.

I got the feeling that Petrie would have grown up to be a man with the usual mix of interests.

One small note on the population: King explcitly gives it as 1,319 people in the 1970 census; but in fairness to the comments on the paedophile priest, I don’t think that Grady Hendrix is talking of Father Callahan at all. There is a throwaway line that would indicate that this is a referance to the Reverand John Groggins, a character that we never meet.

I found it a hugely enjoyable experience to return to ‘salems Lot and he’s certainly correct that you could do your own map from the text, which is what makes an immersion in the town so enjoyable. Not that I’d like to have lived there, even before Straker and Barlow hit the scene.

Sorry Grady, just noticed that you did indeed explain the Groggins refereance. That’s what I get for being a smart-alex and jumping in too soon!

@33: Your comment has been unpublished–feel free to take issue and disagree with the post, but please keep your comments civil and avoid personal attacks on bloggers and other commenters, in accordance with the site’s Moderation Policy.

“The Marsten House will have absolutely nothing to do with anything else in the book…”

Nope. Reading Comp FAIL

Wait, so one thing that bothers me (that no one else has mentioned so I feel justified in raising the issue) is that you label the priest as a pedophile over a vague dream while completely ignoring the confirmed (incestuous) pedophile in the novel – the shady-realtor-who-invites-the-vampire-into-town-but-is-otherwise-irrelevant Larry Crockett.

You might also benefit from re-reading the section where it is expressly stated, by either Barlow or Straker, that Barlow has no wish to buy his way into Salem’s Lot – he requires an invite, which was given to him by Larry for a generous commission on the sale of either the house or the antique store. That might answer your question on why ‘Salem’s Lot in the first place.

Guess idly skimming all that ‘purple prose’ really disadvantaged you when it came to noticing – and then grasping the enormity of – the little things King put into the novel.

Hmm. Pretty uncharitable review. Can’t say I agree with it. It would be easier to respect all these negative opinions, if the reviewer didn’t drop so many factual errors into the mix. You’ve really read this book a bunch of times, but don’t remember the explanation of why Mr. Barlow moves into the Marsten House? Pretty sloppy.

For me, this book has one huge virtue at least – it’s scary. And that counts for a lot. Also, while the characters aren’t the deepest in literary history, they’re much better than this review would suggest. I like Matt Burke, I like Ben Mears. Sure, Susan Norton is a little bland, but isn’t that the point? She represents a perfectly ordinary person caught up in extraordinary events.

Also, someone needs to explain to me how this is a ripoff of Dracula. Aside from “it’s got vampires in it,” how are they really similar?

This may not be a groundbreaking book, but it is awesome. I feel like this review is too concerned with the novel’s production history, and doesn’t convince me that the book itself is bad.

@Brian D.

I think King himself states in Danse Macabre that he was trying to use Dracula as a bit of a template for this novel. Parallels include the staking of Lucy / staking of Susan Norton, the fearless vampire hunters etc.

I first read the book, like so many others, in high school, and certain moments retain a certain chill-factor. The children stuff especially – the MacDougalls and the Glicks.

Actually, we’re told specifically why Barlow appears in Salem’s Lot, and more specifically why he makes his home in the Marsten house. Not because “it’s cheap or has a nice view”. Not because he “wants to turn it into a B&B.” In Stephen King’s world, vampires require an invitation. And it’s made very clear to the reader that a formal, written invitation was issued by Mr. Hubert Barclay Marsten during his trans-Atlantic correspondence with Barlow (then known as Breichen) which extended over a twelve year period between 1927 and 1939. Hubie Marsten was a Boston gangster who took an early and involuntary retirement from his career, receiving as his “pension” a monthly check from a Boston trucking company. Marsten, besides being a hit man for the mafia, was interested in the occult, and he was likely responsible for the mysterious disappearance of four young Salem’s Lot children in the 1930s (whose corpses were never located). Marsten was “introduced” to Breichen by a bookseller in Boston, and that was the beginning of the correspondence that led to Breichen’s invitation to Salem’s Lot. The Boston bookseller met an ugly death in 1933, as he was the only known connection between Marsten and Breichen. In fact, we learn that just before shooting his wife Birdie in the “sun-sticky kitchen” where the “sweet honeysuckle” is as overpowering “as a charnel pit” and then taking his own life by hanging from a noose, Marsten slowly and deliberately burned each page of his correspondence with Breichen in an upstairs fireplace, watching with a smile as Breichen’s “spidery handwriting” is reduced to cinders, erasing all evidence of the invitation that Marsten had issued. This is one of the more fundamental threads that runs throughout the novel and lays the entire groundwork for the cohesiveness of the other storylines.

All of this snobbery about good and bad writing is so dull. King never claimed or pretended to be writing Wuthering Heights. His aim was to write a novel which would scare the pants off us and he succeeded 100%. What book, great or otherwise, doesn’t have ‘paper thin’ characters? If King had given us back stories on each and every one of them we would all be complaining that it diverted from the main story. Yes, Susan is bland but that is the whole point. She represents Everywoman with the inference that she is like us and what happens to her could just as well have happened to any of us. We can’t all be heroes and dragon-slayers. Any novel peopled only with such typed would be boring in the extreme and too far removed from reality to fit its purpose.

I read Salem’s Lot when it was first published. I had never heard of Stephen King before but was intrigued by the black paperback cover with an imprint of a child’s face and a single drop of red blood falling from its lips. I had no idea that this was a vampire novel but I couldn’t put it down and it remains my favourite King novel even though I’ve read almost everything else he has written.

King reinvigorated the horror genre in a way that no-one else had done before him so let’s give him some credit.

Weird as it sounds, the made for TV movie from the 90’s (I think?) actually did a great job of tightening up the plot issues. It combined a lot of the subplots and characters and actually tied Barlow to the Marsten house and what happened in it – making the two actually have something to do with each other. Is it the greatest adaptation I’ve ever seen – no – but it feels like a way more coherent story than the novel, that’s for sure.

I came to comment about the errors in the review, but the cooments have already taken care of those, so I will just say that imperfect as it is, Salem’s Lot scared the s++t out of me back when I was 13 and first read it, and isn’t that an objective proof of how effective the book is?