The second-to-the-last in Stephen King’s big wave of late-80’s blockbusters, Misery came out right after his longest and most ambitious book (It) and right before one of his longest and generally considered most worthless (The Tommyknockers).

At only 320 pages it’s practically a short story for King, and it’s a deeply situational novel, one of his ticking clock thrillers like Thinner or Cujo, but the setting and cast have been greatly reduced. Now it’s two people, and one room. And it pissed off pretty much all of his fans who thought it finally revealed King’s contempt for them. Which is a strange way for them to react because if Misery is anything, it’s a love story.

Misery is one of King’s best-known books in part because it became one of his most successful movies. Starring James Caan and Kathy Bates, it won a “Best Supporting Actress” Oscar for Bates and was directed by Rob “Stand By Me” Reiner and went on to be the third-highest-grossing King adaptation after The Green Mile and 1408. But it’s also successful because it’s good. In more than one interview King refers to editorial input that made Misery better, giving him plot and character ideas and cutting down the length. He says of his success in an interview, “You get all this freedom—it can lead to self-indulgence. I’ve been down that road, most notably with The Tommyknockers. But with a book like Misery, where I did listen, the results were good.”

Misery is one of King’s best-known books in part because it became one of his most successful movies. Starring James Caan and Kathy Bates, it won a “Best Supporting Actress” Oscar for Bates and was directed by Rob “Stand By Me” Reiner and went on to be the third-highest-grossing King adaptation after The Green Mile and 1408. But it’s also successful because it’s good. In more than one interview King refers to editorial input that made Misery better, giving him plot and character ideas and cutting down the length. He says of his success in an interview, “You get all this freedom—it can lead to self-indulgence. I’ve been down that road, most notably with The Tommyknockers. But with a book like Misery, where I did listen, the results were good.”

The idea for Misery came to King in the summer of 1984 while on a trip to England, probably to do some work for the release of The Talisman, his collaboration with Peter Straub that was coming out that Fall. It was right before the film adaptation of Firestarter bombed hard, and less than a year before his identity as Richard Bachman would turn into a publicity firestorm. In On Writing, King writes two very revealing passages about Misery. The first is his account of how the idea came to him. On the American Airlines flight to England he fell asleep and had a dream about a popular writer who fell into the clutches of a psychotic fan. Waking up he jotted the following notes on a cocktail napkin:

She speaks earnestly but never quite makes eye contact. A big woman and solid all through; she is an absence of hiatus. (Whatever that means; remember, I had just woken up.) “I wasn’t trying to be funny in a mean way when I named my pig Misery, no sir. Please don’t think that. No, I named her in the spirit of fan love, which is the purest love there is. You should be flattered.”

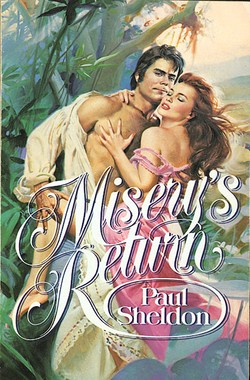

That night at Brown’s Hotel, jazzed on what he thought would turn into a good short story, he couldn’t sleep. The reception desk directed him to a desk on the second floor landing (Rudyard Kipling’s desk, to be precise) where he wrote about 16 longhand pages. His original idea was for a 30,000 word novella to be called “The Annie Wilkes Edition” that would tell the story of Paul Sheldon, a popular romance writer who hates his most popular character, Misery Chastain, a fainting, swooning Victorian romantic heroine. After a car accident his legs are shattered and he’s saved from almost certain death in the snow by Annie Wilkes, his number one fan, who keeps him prisoner until he writes one more Misery novel, just for her. She plans to have it bound in the skin of her favorite pig. Blackout. Six months later, here’s the Annie Wilkes Edition, but it’s not bound in pigskin. It’s bound in Sheldonskin.

That night at Brown’s Hotel, jazzed on what he thought would turn into a good short story, he couldn’t sleep. The reception desk directed him to a desk on the second floor landing (Rudyard Kipling’s desk, to be precise) where he wrote about 16 longhand pages. His original idea was for a 30,000 word novella to be called “The Annie Wilkes Edition” that would tell the story of Paul Sheldon, a popular romance writer who hates his most popular character, Misery Chastain, a fainting, swooning Victorian romantic heroine. After a car accident his legs are shattered and he’s saved from almost certain death in the snow by Annie Wilkes, his number one fan, who keeps him prisoner until he writes one more Misery novel, just for her. She plans to have it bound in the skin of her favorite pig. Blackout. Six months later, here’s the Annie Wilkes Edition, but it’s not bound in pigskin. It’s bound in Sheldonskin.

Set in Colorado (like The Shining and much of The Stand) the book grew beyond King’s original plan when Paul turned out to be smarter than King gave him credit for, finding ways to extend the story. By the time he was done, King had a novel. Looking back, King claims that Annie Wilkes is his favorite character and that the writing of the book was a blast. “As sick with drugs and alcochol as I was much of the time, I had such fun with that one.” And when he says he was “sick” he means that a normal human would be dead. Reportedly sober for about three hours a day, King was guzzling beer and hoovering up cocaine at a staggering rate. In an interview with The Paris Review he even says that the novel was about his addiction:

“Once in a while, something will declare itself so obviously that it’s inescapable. Take the psychotic nurse in Misery, which I wrote when I was having such a tough time with dope. I knew what I was writing about. There was never any question. Annie was my drug problem, and she was my number-one fan. God, she never wanted to leave.”

The second mention of Misery in On Writing doesn’t actually mention the book by name. In the novel, Paul’s legs are shattered in a car accident and he’s imprisoned by Annie Wilkes and forced to write another Misery story. He bangs out a draft but Annie refuses to accept his first pages, complaining that they don’t play fair with the reader. She also makes him burn the manuscript whose completion he was celebrating when he ran off the road—a dire literary fiction effort about a poor, Hispanic car thief from the ghetto. After his initial rage and shock passes, Paul realizes that Annie was right on both counts—his literary fiction books suck, and his new Misery book doesn’t play fair with the reader—and, under duress, he revises his Misery manuscript. As he does, inspiration strikes, and he begins to write in a white hot passion, compelled to finish his book even though he knows Annie will kill him the second he types The End. It turns out to be the best book of his career.

The second mention of Misery in On Writing doesn’t actually mention the book by name. In the novel, Paul’s legs are shattered in a car accident and he’s imprisoned by Annie Wilkes and forced to write another Misery story. He bangs out a draft but Annie refuses to accept his first pages, complaining that they don’t play fair with the reader. She also makes him burn the manuscript whose completion he was celebrating when he ran off the road—a dire literary fiction effort about a poor, Hispanic car thief from the ghetto. After his initial rage and shock passes, Paul realizes that Annie was right on both counts—his literary fiction books suck, and his new Misery book doesn’t play fair with the reader—and, under duress, he revises his Misery manuscript. As he does, inspiration strikes, and he begins to write in a white hot passion, compelled to finish his book even though he knows Annie will kill him the second he types The End. It turns out to be the best book of his career.

At the end of On Writing is a chapter called “On Living: A Postscript.” In it, King talks about shattering his legs when he was struck by a van. During his painful recovery he got addicted to painkillers, just like Paul Sheldon in Misery. But his wife and constant nurse, Tabitha King, provided him with a space to write and helped prop him up every day to complete On Writing no matter how much pain he was in. To King’s surprise, On Writing crossed over and became one of his biggest successes, pleasing both his genre fans and literary critics alike. And it was all thanks to his nurse who made him put up with the pain, Annie Wilkes Tabitha King.

There’s a lot going on in Misery but many fans reacted as if there was just one: King hated them. In March of 1987, about three months before publication, King was burnt out. He had finished The Tommyknockers the summer of the year before and ever since he’d been unable to write. “Everything I wrote for the next year fell apart like tissue paper,” he said. So, in March, it was announced that he was retiring. It was a huge publicity bump for his next book, Misery. Fans were outraged (how dare he quit, he owed them more books!) the same way they’d been upset the month before when Eyes of the Dragon was published (how dare he write fantasy, he owes us horror!). When they picked up copies of Misery and found a savage dissection of the dark side of fandom they were outraged some more. King spent his publicity tour reassuring his fans that it wasn’t them he was talking about, it was those other fans, and Tabitha even wound up writing two pieces in Castle Rock, the King fanzine, reminding fans that they neither knew their favorite author, nor owned a piece of him.

There’s a lot going on in Misery but many fans reacted as if there was just one: King hated them. In March of 1987, about three months before publication, King was burnt out. He had finished The Tommyknockers the summer of the year before and ever since he’d been unable to write. “Everything I wrote for the next year fell apart like tissue paper,” he said. So, in March, it was announced that he was retiring. It was a huge publicity bump for his next book, Misery. Fans were outraged (how dare he quit, he owed them more books!) the same way they’d been upset the month before when Eyes of the Dragon was published (how dare he write fantasy, he owes us horror!). When they picked up copies of Misery and found a savage dissection of the dark side of fandom they were outraged some more. King spent his publicity tour reassuring his fans that it wasn’t them he was talking about, it was those other fans, and Tabitha even wound up writing two pieces in Castle Rock, the King fanzine, reminding fans that they neither knew their favorite author, nor owned a piece of him.

King was no stranger to crazy fan behavior by that point, and subsequently while he was out of town and his wife was home alone a deranged fan broke into his house with a box he claimed was a bomb, ranting that King had stolen the idea of Misery from him. But the fan outrage missed the point, Misery was about how King needed his fans the same way Paul Sheldon needed Annie Wilkes. Someone had to hold his feet to the fire and demand that he play fair with his characters now that he was too big for an editor to control.

Throughout the book, Annie is described as a horror show. She has earwax clogging her ears, her breath is rank, her body stinks, she is described as “solid all the way through” with no soul. Paul, a writer with shattered legs, an addiction to pain pills, a man who probably doesn’t smell so great himself, and who pees himself at every opportunity is spared such grotesque descriptions (except of his shattered legs, which horrify him as well). Paul Sheldon is an egotist, a man with a blind spot shaped exactly like himself. He is petulant and whiny throughout because, as much as Annie imprisons him, as much as she threatens him, as crazy as she acts, without her, he’d be dead. The same with King and his fans.

Throughout the book, Annie is described as a horror show. She has earwax clogging her ears, her breath is rank, her body stinks, she is described as “solid all the way through” with no soul. Paul, a writer with shattered legs, an addiction to pain pills, a man who probably doesn’t smell so great himself, and who pees himself at every opportunity is spared such grotesque descriptions (except of his shattered legs, which horrify him as well). Paul Sheldon is an egotist, a man with a blind spot shaped exactly like himself. He is petulant and whiny throughout because, as much as Annie imprisons him, as much as she threatens him, as crazy as she acts, without her, he’d be dead. The same with King and his fans.

As King has said numerous times, the fans put food on his table. He hates them, but he owes them his life. And there are moments when Paul is waiting for Annie to react to something in the manuscript he’s writing that he knows will thrill her, or upset her, when it feels like her reaction is vital for his continued existence. He imagines her reaction and then revels in it when it comes, and one can imagine this is how King felt too. He has written for his readers (Constant reader as he calls them in his introductions) for so long that to some extent his books are collaborative: if a book is released to the public and no one reads it, does it even exist at all?

A love/hate letter to his fans, Misery is one of King’s most popular books. With a first printing of 900,000 copies, it was the fourth-most-popular hardcover book of 1987, and by 1990 it had sold 875,000 copies, making it the 15th most popular book of the decade. But King couldn’t keep his demons at bay for much longer. Misery represented a fragile peace he made with them, but his next book, The Tommyknockers, would see him go down the rabbit hole of his own ego and substance abuse problems.

A love/hate letter to his fans, Misery is one of King’s most popular books. With a first printing of 900,000 copies, it was the fourth-most-popular hardcover book of 1987, and by 1990 it had sold 875,000 copies, making it the 15th most popular book of the decade. But King couldn’t keep his demons at bay for much longer. Misery represented a fragile peace he made with them, but his next book, The Tommyknockers, would see him go down the rabbit hole of his own ego and substance abuse problems.

BONUS ROUND:

When Rob Reiner and his producer, Andy Scheinman, read Misery they assumed someone had already bought the rights and were surprised that not only did King still have them, but they weren’t for sale. Feeling burned by previous adaptations of his works (he was publicly unhappy with The Shining, in court over The Lawnmower Man using his name, and burned by a string of flops that had devalued his box office name) King was no longer offering the film rights to his books. Because he loved Stand By Me, which Reiner had directed, he agreed to let him have it for a very high fee, and with the condition that Reiner had to either produce or direct. After Reiner’s first two director choices turned him down (George Roy Hill and Barry Levinson) he decided to direct it himself.

Grady Hendrix is the author of Satan Loves You, Occupy Space, and he’s the co-author of Dirt Candy: A Cookbook, the first graphic novel cookbook. He’s written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today and his story, “Mofongo Knows” appears in the anthology, The Mad Scientist’s Guide to World Domination.