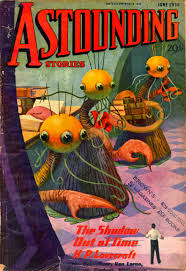

Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at “The Shadow Out of Time,” first published in the June 1936 issue of Astounding Stories. You can read the story here. Spoilers (and concomitant risk of temporal paradox) ahead.

Summary: Nathaniel Peaslee is normal. Though he teaches at Miskatonic University in whisper-haunted Arkham, he comes from “wholesome old Haverhill stock.” He’s married, with three kids, and has no interest in the occult. But during a lecture, after “chaotic visions,” he collapses. He won’t return to our normal world for five years, though his body soon regains consciousness.

See, the mind now inhabiting Peaslee is not Peaslee’s. Awkward in movement and speech, he appears victim of a rare global amnesia. Eventually his movements and speech normalize. His intellect grows sharper than ever. His affect, however, remains so profoundly altered that his wife and two of his children break off all contact.

New Peaslee doesn’t mourn their defection. Instead he devotes himself to two studies: the present age and the occult. He’s rumored to associate with cultists and to have an uncanny ability to influence others. His travels are wide and weird.

Five years post-collapse, Peaslee installs a queer mechanism in his home. A dark foreigner visits. Next morning the foreigner and mechanism are gone, and Peaslee again lies unconscious. He awakens as good old normal Nathaniel.

Or maybe not so normal anymore. Along with the expected travails of an interrupted life, Peaslee contends with strange sequelae. His conception of time is disordered—he has notions of “living in one age and casting one’s mind all over eternity.” And he has nightly dreams that grow in detail until he virtually lives (or relives) another existence in his sleep.

Peaslee studies every known case of similar amnesia. Common to them is the victim’s impression of suffering an “unholy sort of exchange” with some alien personality. His case parallels others down to details of the post-recovery dreams. Alienists attribute this to the mythological studies pursued by all secondary personalities under the sway of this condition.

These myths posit that man is only the latest dominant race on Earth. Some races filtered down from the stars; others evolved here. One ruled more than a million years spanning the Paleozoic and Mesozoic ages: the Great Race of Yith, which can project its minds through time and space. The process, part psychic and part mechanical, causes an exchange of personae, with the Yithian taking over the target’s body, while the target’s mind ends up in the Yithian’s body. Using this technique, the Yithians explored past and future, becoming effectively omniscient, and repeatedly escaping extinction through mass exchange with younger species.

Legend accords with Peaslee’s dreams of titanic alien architecture amidst prehistoric jungle, peopled by ten-foot cone-shaped beings. In his dreams, he too wears this form. He gradually advances from captive to visiting scholar, given freedom to explore while he writes a history of his own time for the Yithians’ transgalactic archives.

It appalls Peaslee how well mythology explains the sequelae of his amnesia: his phobia of looking down and finding his body inhuman; notes made by his secondary personality in “Yithian” script; his sense of an externally imposed mental barrier. Supposedly before a reverse exchange, the Yithians purge displaced minds of their “Yithian vacation” memories. However, he still believes these memories to be hallucinatory.

Slowly Peaslee’s life returns to normality. He even publishes articles about his amnesia. Instead of bringing him closure, the articles draw the attention of a mining engineer who’s discovered ruins in Australia’s Great Sandy Desert—ruins that resemble his dream architecture. Peaslee organizes a Miskatonic expedition and embarks for Australia.

The excavation stirs up Peaslee’s anxieties, especially when they uncover another style of architecture: basalt blocks that figure in his quasi-memories as remnants of a pre-Yithian race. The Elder Things came from “immeasurably distant universes” and are only partly material. These “space polyps” have psychologies and senses wildly different from terrestrial organisms, are intermittently invisible, can stalk on five-toed feet or hover through the air, and summon powerful winds as weapons. The Yithians drove them into underground abysses, sealing them behind guarded trapdoors.

But the Yithians have foreseen an irruption of Elder Things that will destroy the cone-shaped race. Another mass migration will save the Yithians’ minds. They’ll project themselves into Earth’s future and the sentient beetles that rule after humankind when the Elder Things will be extinct.

During man’s time, the Elder Things have become inactive. The aboriginal Australians whisper, however, of subterranean huts, of unnatural winds out of the desert, and of a gigantic old man who sleeps underground, one day to devour the world.

Peaslee reminds himself that if the Yithians are creatures of myth, so are the Elder Things. Even so, he wanders at night, always toward an area that draws him with mixed sensations of familiarity and dread.

One night Peaslee discovers cohesive ruins and an opening into relatively intact underground levels. A sane man wouldn’t venture below alone, armed only with a flashlight. But he knows the place as well as he knows his Arkham home and scrambles over debris in search of…what? Not even the sight of open trapdoors deters him.

He can no longer deny some great civilization existed eons before man. Can he find proof that he was once its “guest”?

Peaslee arrives at his dream archives. Built to last as long as Earth itself, the library is whole, and he hurries toward a section he “knows” to house human memoirs. En route he passes toppled shelves. Five-toed footprints lead to an open trapdoor. Peaslee proceeds cautiously.

He reaches a certain shelf and, using a quasi-remembered code, he extracts a metal-cased tome. After trembling hesitation, he shines his flashlight on its pages. He collapses, biting back screams. If he’s not dreaming, time and space are fluid mockery. He’ll bring the book to camp and let others verify what he’s seen.

Retracing his steps, Peaslee unluckily starts a debris avalanche. Its din is answered by the shrill whistles of the Elder Things. To escape, Peaslee must skirt trapdoors now belching whistles and blasts of wind. Worse, he must vault a crevasse from which issues “a pandaemonic vortex of loathsome sound and utter, materially tangible blackness.” Falling through “sentient darkness,” he undergoes another possession, this time by horrors accustomed to “sunless crags and oceans and teeming cities of windowless basalt towers.”

This blows his shaken mind, but semi-conscious he labors to the surface and crawls toward camp, battered and minus his book.

During his absence, hurricane-force winds have damaged the camp. Without explanation, Peaslee urges the others to call off the expedition. Though they refuse, airplane surveys don’t find his ruins. The windstorm must have buried them.

If the ruins ever existed. Peaslee’s lost the relic that would have proved his dreams to be memories. Sailing home, he writes his story. He’ll let others gauge the reality of this experience, whether there indeed lies over mankind a “mocking and incredible shadow out of time.”

Oh, and that book? It wasn’t written in alien characters, just in the normal words of the English language, in Peaslee’s normal handwriting.

What’s Cyclopean: Yithian hallways—twice! Masonry fragments in modern Australia—also twice! And a “sinister, Cyclopean incline” in the ruins! This is a great story for adjectives in general: fungoid plants! A gibbous moon! An eldritch rendezvous! Shambling horrors! The Yith are “immense rugose cones.” A great opportunity is lost, alas, when he calls them as “scaly” rather than “squamous.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Aside from a reference to “squat, yellow Inutos,” and an engineer who calls the Australian aborigines “blackfellows,” this story doesn’t have much blatantly racist description. It has a lot of “everyone but white people has true legends about this,” but that seems pedestrian and modern compared to his usual rhetoric. Really, you might as well read Twilight.

Mythos Making: The Yith—historians of the solar system and maybe the universe—tie the Mythos together more effectively than Ephraim Waite. Here we get the full horror and glory of deep time, and the sheer abundance of intelligences populating earth and the universe. Then there are the Elder Things—the Yith’s mortal enemies, who once ruled half the solar system.

There’s a through-line of fear that the people you displaced will return to take their vengeance. The Yith drive the Elder Things into subterranean prisons, and the Elder Things eventually drive the Yith forward into post-human beetle bodies. The story of the forcibly switched beetle people fighting the Elder Things must be an interesting one. And of course, it’s one of the few stories lost to the Archives, unless they decided to add it on their own.

Libronomicon: In addition to the Archives themselves, we get Cultes des Goules by Comte d’Erlette, De Vermis Mysteriis by Ludvig Prinn, Unaussprechlichen Kulten by von Junzt, “the surviving fragments of the puzzling Book of Eibon”, “the disturbing and debatable Eltdown Shards,” and “the dreaded Necronomicon of the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred.” “The frightful Pnakotic Manuscripts” are one of the few things to survive a Yith-caused temporal paradox. Journal of the American Psychological Societyappears to be fictional, although an organization of that name existed briefly in the late 80s before becoming the Association for Psychological Science.

Also, the Yith really are evil: they write in the margins of rare library books.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Peaslee obsesses over whether his experiences are real or hallucination—he hopes desperately for the latter, in spite of his insistence that he’s not mad. He insists that what he has isn’t “true insanity” but a “nervous disorder.” I must have missed that distinction in the DSM.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

The Yith! The Yith! This is limbs-down my favorite Lovecraft story: an exhilarating piece of nearly plot-free master worldbuilding, in which the problematic bits don’t so much scream in your face as lurk formlessly and horribly beneath unspeakable, half-rotted trap doors.

The Yith may be the most interesting—and horrifying—thing Lovecraft ever created. An exchange with the Yith has the same appeal as jumping into the TARDIS: it may destroy your life and your sanity, but… five years in the world’s best library. Five years in the world’s best conversation. Five years traveling alien cities and exploring a prehistoric world. This is the really appealing thing about the best Lovecraft—the idea that learning is that powerful, that dangerous, that risky… and that worth the cost.

The Yith, however, offer one more thing that the Doctor does not: a legacy. Lovecraft was nearing the end of his short life when he wrote this. Given his profession and predilections he must have thought about how long writing can last. Five thousand years is the oldest we have, and most from that period is lost or untranslated. The idea that whole species can rise and fall, culture and art and invention all swallowed by entropy, is terrifying. How much of one short mortal life would you give up, to guarantee that your story would last as long as the Earth—or longer?

Of course, exchange with the Yith is deeply nonconsensual—not a minor difference, and a very personal violation that goes pretty much unexplored here. This thing comes in and casually takes your body and your life, without regard for the fact that you have to live in them afterwards. And yet, Lovecraft seems to see greater horror in the mere existence of the “great race’s” greatness, the fact that they surpass humanity’s own achievements—the “mocking and incredible shadow” of the title.

On another level, Peaslee talks constantly about how terrible it would be if his dreams were true—and yet he grows accustomed to his alien body, treats the other captive minds of China and South Africa and Hyperborea and Egypt as a community of equal scholars. Maybe this is Lovecraft finally trying to come to terms with living in a multicultural society—and kind of succeeding?

But it’s more complicated than that. The Yith could be Lovecraft’s argument with himself about what makes a race “great.” Is it perfect cultural continuity, the ability to preserve history and art for aeons unchanged? Or is it—against all of his bigoted instincts and fears—the ability to be endlessly flexible in form and appearance, to take on whatever aspects of one’s neighboring races seem interesting and desirable? The Yith survive and prosper because they work with and learn from all other races and times. And yet, they are also the ultimate colonists, literally destroying entire species by appropriating their cultures, their cities, their bodies and minds. Maybe even at his best, Lovecraft thought that was the only way to survive contact.

Anne’s Commentary

In the core Mythos stories, Lovecraft placed humanity on a micrograin of sand in a dauntingly vast cosmos. In “The Shadow Out of Time,” he concentrates on Professor Einstein’s “new” dimension. Time’s no cozier than space, especially as explicated by the Great Race of Yith. Masters of temporal projection, they’re historians unsurpassed in literature. What’s more, mess too much with these guys and they’ll simply cash in their frequent time travel millennia and mass-mental-migrate out of there.

Hate it when that happens.

Still, asked to trade places with a Yithian scholar, I’d be all: Snatch my brain? Yes please! Even anxious Peaslee acknowledges that for a keen mind, this opportunity is “the supreme experience of life.” Sure, you might discover horrors like the Elder Things and the ultimate fate of your race, but you’d also hang out with minds from all over the time-space continuum, in the most fabulous library ever conceived. And how bad could living in a rugose cone be? At least you’d be free from the problems that beset us sexual reproducers, like getting a date for Saturday night.

Speaking of family matters, there’s this one big drawback. Tough on relationships when you suddenly become a stranger to your loved ones—Peaslee loses all but one son to his “amnesia.” If only the Yithians would let you phone home to say you’d be back in a bit. Evidently the long distance fees from the Paleozoic are prohibitive.

Which leads me to new-to-this-reread ruminations on Yithian ethics. They treat displaced minds kindly and give the cooperative fantastic perks. But then they brainwash away memory of the experience and drop the displaced back on doorsteps where they may no longer be welcome. And that’s if the bank hasn’t already foreclosed on the doorsteps. The Yithians also punish any member who tries to escape impending death by stealing a body in the future. But doesn’t the Great Race repeatedly commit genocide with its mass migrations, condemning the transferred minds of whole species to extinction?

Don’t care who you are, that’s not playing nice. Although if humans could avoid extinction, how many would pass? As far as we know, the only Yithians left behind are those unfit for time travel, not conscientious objectors. And leaving people behind opens another can of shoggoths, ethics-wise. Finally, what if there are more members of the target species than there are Yithian minds to inhabit them? Do the freshly re-embodied Yithians then eliminate the non-Yithian remnants?

Good stories and world building let us ponder these kinds of issues, even if not directly referenced by the author.

World building, though. Also new to this re-read is my plunge into a possible hole in it. What the Yithians’ original bodies were like, we don’t know, but they abandoned them, packing only their minds for the migration forward. What underwent temporal projection? Certainly not the physical brain but patterns of thought and perception, memory, will, temperament, all the things that make up individuals and their culture.

Not genes, though, the biochemical blueprints of individuals and race. Assuming it’s a sort of psychic plasma Yithians project, it wouldn’t contain DNA, a material molecule. Knowledge of genetics they must carry along, part of their “omniscience.” They don’t seem to use this knowledge to alter host bodies. Maybe wholesale genetic modification is beyond their technology. Maybe they choose not to alter hosts—after all, the hosts are finely adapted to environments alien to the original Yithians.

Bottom line: Cone-form Yithians have cone-form genes, right? Once projected from their ur-forms, wouldn’t Yithians be unable to spawn NEW Yithians? The cone spores they culture in their tanks would produce cone bodies with cone minds, not Yithian ones. Further: the entire Great Race population must consist of the minds that escaped extinction on dying Yith, minus any who’ve since died.

So the Great Race shouldn’t treat the death of any individual Yithian lightly. With the Race’s numbers finite, every Yithian mind should be precious, and escaping personal death shouldn’t be a crime.

Not that dying Yithians would need to project into the future. New hosts could be reared to receive endangered Yithian minds, thus keeping the Yithian population in stasis. Sudden accident or illness or violence would be the only ways Yithians died; the rest would be essentially immortal.

The hole, if it’s that, isn’t surprising. Mendel had set down the principles of inheritance before Lovecraft’s birth, but it would be decades after his death before Watson and Crick modeled the tricksy-twisty structure of DNA. Lovecraft seems to have assumed that once a creature had a Yithian mind, it became Yithian right down to producing true Yithian babies. Interesting! As if mindset rather than genetics makes a race. But can mindset remain unaltered in a new body and environment? Are Yithians Yithian whether in ur-forms or cones, men or beetles? Can Peaslee remain same old Peaslee when he glides on a slug foot and communicates via clicking claws?

Hey, this identity question came up in our re-read of “The Thing on the Doorstep!” Huh.

Yeah, many “cyclopeans” here, though Lovecraft throws in some “titans” for variety. Still, the repetition that struck me was “normal.” Peaslee insists his “ancestry and background are altogether normal.” It’s the “normal world” from which the Yithians snatch him. After post-amnesia troubles, he returns to “a very normal life.” Entering the Australian ruins, he’s again sundered from “the normal world.”

Yet in the buried city, normality becomes relative. Traversing his dream-corridors in the flesh, Peaslee knows them “as intimately as [he] knew [his] own house in Crane Street, Arkham.” The normal and its converse switch places. He feels “oppressed by a sense of unwonted smallness, as if the sight of these towering walls from a mere human body was something wholly new and abnormal.” He’s disturbed by the sight of his human body and human footprints. While underground, he never glances at his watch—normal time means nothing in the seat of its conquerors. And what could be more normal than one’s handwriting? Unless, of course, it’s where it shouldn’t be; and yet, logically, inevitably, normally, how could it not be there?

Actually, the cone form is normal neither to Peaslee nor the Yithians, which makes them fellows in adaptation.

I can’t close without mention of this story’s entry into Lovecraft’s Irremediably Weird Bestiary. The Elder Things are like shoggoths in “At the Mountains of Madness”: No amount of exposure will reconcile Peaslee to these critters. The Yithians are cuddly in comparison.

God, I love Elder Things.

Oh, and speaking of “Mountains,” it’s ironic fun to see William Dyer join the Miskatonic expedition to Australia, considering what happened on his Miskatonic expedition to Antarctica. This dude’s a glutton for worldview-annihilating exploration!

Join us next week for the short but sweet “Terrible Old Man.”

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available June 24, 2014 from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.

Ruthanna Emrys’s novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com. Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. Having studied way too much psychology, she doesn’t buy that whole thing about the Yith not having a sense of touch—she doesn’t care how alien you are, if you don’t pick up on tissue damage, you aren’t living any 5000 years.

I also think this is one of his strongest, though rather more SF than horror. The final reveal isn’t the strongest but it’s interesting to spend some time with an admittedly ruthless but not all that hostile mythos species (bordering on utopian from a certain point of view, Lovecraft nearly launches into the “tour of the factory” at one point), while there’s a sense of untold eons in which humanity is almost insignificant, generating equal amounts of terror and awe.

Here’s what else was in the June 1936 issue of Astounding Stories:

The second part of the serialisation of Jack Williamson’s classic space opera The Cometeers appears in this issue.

One of Ross Rocklynne’s (somewhat implausible) “Colbie and Deverel” Hard SF puzzle stories. If I remember correctly, “At the Center of Gravity” is the one where they are trapped within a hollow sphere.

An essay by John W. Campbell appears. He would later go on to edit Astounding but, in Mythos terms, he is best known for the Retro-Hugo nominated “Who Goes There?” which appeared as “The Thing from Another World” in Chaosium’s The Antarktos Cycle.

There were also stories by Nat Schachner (two, actually), Stanton A. Coblentz, Nelson Tremaine and Clifton B. Kruse. The cover artist is Howard V. Brown.

And I must say that the original Astounding Stories cover above shows Yithians so CUTE they ought to be endlessly retweeted as Emergency Aliens.

Mom, can I take them home? I’ll feed ’em, I’ll walk ’em, I’ll clean the litter box, I promise!

Too bad Lovecraft didn’t have the presence of mind to keep his Mythos to himself, found a religion based on it, and charge initiates tons of money to learn its secrets. He’d have lived in comfort and died rich.

S

AMPillsworth@3,

My thoughts exactly- they’re cuddlier than E.T!

I just want to point out:

That gibbous is the actual name for the phase of the moon when it’s 3/4 full, and not authorial wordplay. Waxing gibbous if it’s right before the full moon, and waning gibbous if it’s right after.

I can’t express how much I enjoyed reading this story. Some how I had missed it when I originally read the collection this story was in. Unlike the previous story, this one touches on my favorite theme of Lovecraft’s: knowledge is dangerous. Lovecraft is one of the reasons I have started reading history books and the like because there are always those little crazy facts that will just blast your mind into oblivion and make you rethink everything.

The Yith, while mostly harmless, actually seem to me to be one of the most horrifying races that Lovecraft conjured out of his fevered imagination. Imagine if the Yith had lived till the end of the dinosaurs and chosen humanity instead of the Beetles. One moment we’re going about our day, the next we are in alien bodies staring up at an asteroid with our names on it and no possibility of salvation. That is a scary way to die, not even allowed to be ourselves when we die.

As for the Yith as a race and reproducing, I agree with Ruthanna that Lovecraft may have finally worked out some of his racist problems with his creation of this species. They take the greatest minds of all time (Yith as the first Borg) and adapt themselves to that new knowledge. Genius doesn’t see racial differences. What makes the Yith so Yithy isn’t what planet they were from, they gave all that up in the migration as any sense of bodily identity. What they have now is shared culture and knowledge. So any cone creatures born post-migration are still Yith because the body doesn’t matter, only the mind. We may be getting their eventually ourselves thanks to the Internet, whether I look like Chris Farley or Brad Pitt doesn’t matter here, just the words that show up under my name.

Now when it comes to Lovecraft viewing their migration, I think that would be less overt racism than just an expected outcome of the social darwinism that seems to have affected a lot of the thinking of the time. The strongest society naturally gets the best of everything in the same way as the lions eat the antelope. Nothing racist about it, just survival.

While not as obvious as an overt racial slur, social darwinism is actually an aspect of racism–one of the concepts, along with manifest destiny, that reassures the people in power that their position at the top of the heap is inevitable and unavoidable. And therefore makes it so urgent to prove that everyone else is weaker.

TL; DR: Lovecraft’s lack of subtlety shouldn’t blind us to the fact that racism is actually a set of harmful social and linguistic constructs, not just blatant expression of hatred.

On the internet no one knows you’re a Yith? Unless that’s where the particularly pedantic sort of troll comes from. Oh dear.

Hellzie @@@@@ 6: Lovecraft uses all of his adjectives entirely according to their definitions. But point taken: gibbous is more commonly used, by people who are neither Lovecraft nor riffing on his work, than several of those other words.

Anne @@@@@ 3: “I leave behind this missive in the hopes that others may learn from my errors…”

Ruthanna @@@@@ 8 Aw. Well, if I can’t have a Yith, can I at least have an Elder Thing? They make great vacuum cleaners.

Hellzie @@@@@ 6 I always image a “gibbous” moon as either gibbering or being somehow related to the gibbons.

I’ve always found this one more intriguing than scary. The temporal exchange program isn’t voluntary, but it certainly sounds interesting.

Oddly enough, I had completely forgotten the post-return portion of this story. The only thing which stuck was the mindswap, even though the Australian portion was the basis for one of Larry DiTillio’s better Call of Cthulhu adventures.

HPL may have missed out on a chance to use squamous, but he did give us rugose here. That’s only like half a point not as good.

Another thing about the world building here is Lovecraft playing with a hip political flavor. IIRC, the Yithians are essentially fascistic (in the specific politico-economic sense). There’s another story which escapes my recollection right now where he gives us a socialistic non-human society (“Mountains of Madness”?). His horizons are clearly broadening beyond his pseudo-aristocratic New England upbringing.

Of course that does raise the horrifying question of “why aren’t they choosing us?”. WHat is going to happen to humanity that makes us so unsuitable for Yithian takeover. It must be pretty bad for them to have peered into our future, and gone “yah, you know what. Lets skip these guys, they are so doomed”. That cannot bode well for humanity.

Speaking of the post-return. Peaslee is either being extremely circumspect about his family situation (which is, he practically doesn’t have one anymore) or Lovecraft is preternaturally uninterested in the domestic drama. I’m voting on the latter. There is that one extremely loyal son Wingate, so I must suppose that Peaslee had been a warm enough father prior to dislocation to have inspired that loyalty.

Anyhow, yeah. I think Lovecraft’s interest in family dynamics has already reached its height in our reread, with “Thing on the Doorstep.” Though there IS some nice dysfunctionality to be savored in “Dunwich Horror.”

Random22 @@@@@ 11: I think the Yithians didn’t want to settle into any era during which the Elder Things were still alive, however debilitated. But, yeah, you have a good point. There could be worse than relatively tame Elder Things in our future, like a Shark Week that lasts ALL YEAR!

Yeah “gibbous” was never one of my Lovecrafts-of-the-Day.

This is way more Scifi Lovecraft than Horror Lovecraft. There was much more sense of horror at the Thing on the Doorstep than here. But the horror is replaced by the description of a very interesting society. What some people wouldn’t give to spend some time at the library of everything!

Not only was there a mention to Hyperborea (Clark Ashton Smith’s stories), but also to Cimmeria (a guy named Crom-Ya), making this a reference as well to Robert E. Howard’s works. Robert E Howard died on June 1936, so this edition of Astounding Stories would in the future be somewhat sentimental to Lovecraft, I think.

One of my favorites also.

Despite that I always felt like the emergence of the flying polyps sounded more of an eruption than an irruption.

Despite no one has yet checked to see whether or not basalt figures more in descriptions of evil or sinister architecture than other types of stone–if so, would this be because of its dark color?

Despite wondering if he described the Inutos as squat because he himself was tall and thin, or if there was a more general prejudice against short and broad-built people vs. tall, slim, “aristocratic” types? I read somewhere that the craze for tall, skinny models started early in the last century…

Still, quite a story, and a good analysis.

I’m reading Lovecraft for the first time following this reread. In this story I thought with a different protagonist the same events could have been an exciting opportunity to study all those alien cultures instead of a horror story. Discovering that it was all real should good (proving that he isn’t mad), not a terrible thing. He focuses too much on his xenophobia to enjoy the opportunity to learn.

There are a few choices for devotees to experience this story in a different medium. Alas, no films as far as I know.

One of the jewels in the Lovecraftian universe is the HP Lovecraft Historical Society. They create wonderful old time radio plays with their Dark Adventure Radio Theatre. Of coure they did a superb job on The Shadow Out of Time: http://www.cthulhulives.org/store/storeDetailPages/dart-soot-cd.html

The Shadow Out of Time is a pretty long story so it has only a few comic book adaptations. The earliest version I know about was by Larry Todd in 1972, found in the old underground comic Skull #5. It was retitled The Shadow from the Abyss. In Graphic Classics #4 (their Lovecraft edition), Matt Howarth adapted The Shadow Out of Time. Most recently, Selfmadehero has been releasing excellent Lovecraft comics. INJ Culbard has tackled the longer novellas and stories. His estimable version came out in 2013.

Pete Von Sholly is providing copious amounts of art for a lovely series of illustrated Lovecraft stories from PS Publishing. Not yet released, The Shadow Out of Time is going to be included in these titles.

Finally, I can’t stop without mentioning the superb renditions of the HP Lovecraft Literary Podcast. They did a 4 part of The Shadow Out of Time in 2012: http://hppodcraft.com/?s=shadow+out+of+time&submit.x=-1063&submit.y=-190

Oh, and everyone worried about the Elder Things needs to watch this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BWT07iRvI9M

birgit @17 reminds me of a point I wanted to make earlier. This story is unusual in that the protagonist is far more disturbed at the idea that his experiences are real than the thought of going mad. Lovecraft was greatly troubled by the fact that both his parents ended up institutionalized. No doubt something his aunts used to browbeat him with. There’s even a decent argument that the “taint in the blood” which informs “The Shadow over Innsmouth” is insanity rather than non-human/non-white ancestry.

But here, Peaslee would much rather believe that his 5 years of amnesia and abberant behavior, followed by years of disturbing dreams and pseudo-memories, are the result of a fevered brain. The truth of deep time, an indifferent cosmos, and mankind’s insignificance in the place of it all is just too much for him. Far better to be a lunatic.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 20 See, this is what’s so fascinating about many of HPL’s protagonists. They are both terrified by the truth and drawn to it. Peaslee protests too much, I think, that his experiences were only delusion, and damn good thing, too. He also goes to extraordinary measures to prove himself wrong about this, as in going to Australia at all and then plunging into the underground labyrinth for the final straw — or tome — to break the delusion-camel’s back.

And as Peaslee himself notes, for a person of intellect, to sojourn among the Yithians must be the ultimate experience of life.

Repulsion, attraction, fascination. Again and again. Acceptance, even ecstatic, is not impossible, as we’ll see a few weeks down the line in the other great “Shadow,” that over Innsmouth.

@16: A quick search reveals quite a few references to basalt in Lovecraft’s stories, including “The White Ship”, “The Hound” and “The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath”. Must be an unusually cyclopean rock… I think irruption suits: it is either to break in or, in ecological terms, to increase rapidly in number.

@18: Culbard on “The Shadow Out of Time” and adapting Lovecraft: http://www.digitalspy.co.uk/comics/interviews/a490157/inj-culbard-on-the-shadow-out-of-time-and-the-joy-of-lovecraft.html#~oMPbpl2rNeT1DR. There’s also a gleefully cheesy low-budget film on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y7jp1CP1h6c#t=710.

@19: I’ll hold off ordering until they come up with something that deals with the Hounds of Tindalos, so that I wouldn’t have to write this from inside a smooth white sphere.

@16/22

One of the things about basalt is that it fractures naturally into geometric shapes that look like (cyclopean) constructions. A good example is the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland. That makes it a good candidate for the ruins of long-forgotten civilizations.

I thought the Yith skipped humans mainly because we are so short-lived, considering the cones could live thousands of years and how they weren’t into body-switching to avoid individual death. The beetles must be less fragile.

I can also imagine the way we reproduce rather horrified them ;)

Did anybody else read this and immediately think about Barbara Hambly’s Time of the Dark series?

This is one of my favorites (probably just ahead of Mountains of Madness; Kadath is also a favorite, but that seems like it belongs on a different list).

It’s interesting to read the later-period stories (Shadow, Mountains and Whisperer, in particular) and see how he keeps building on and expanding the history of the universe — Mountains is all about the star-headed Old Ones, and in Shadow we discover that the Yith predated them (and fought terrible wars with them back in the day).

Also, Cthulhian scholarship must have been undergoing a massive renaissance during the 1920s & 1930s — at the time of Call of Cthulhu, nobody had any idea that these things were all around, but by the time of Shadow, Arkham University darned near had a Chair of Cthulhoid Studies.

(And Hippocampus Press put out a really nice edition of Shadow several years ago — a corrected text with extensive notes by S. T. Joshi and David E. Schultz. And it used that Astounding cover pictured above.)

I keep misreading comments about the Yith taking over the Beatles. I am not writing this story. Or the story where Yoko Ono visits the Archives, either. Brain, what is wrong with you.

AMPillsworth @@@@@ 9: Bad cultist, no shoggoth.

Ryamano @@@@@ 15: One of the things I do enjoy is getting glimpses of Lovecraft’s community of fellow writers, all cheerfully playing in each other’s sandboxes and blurring the boundaries.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 20: There seems to be a conflict between the desire to be normal and the desire to preserve a normal, time-limited worldview. He does make rather a point of his non-lunacy. He’s just, y’know, the kind of neurotic-but-not-insane person who has weird ultravivid hallucinations of alien cities. Happens to everyone. Especially at Miskatonic.

One of these stories, I’m gonna get into Lovecraft’s fraught relationship with mental illness (entirely typical of the time, one suspects), and the ways that his portrayals of “madness” are still feeding nasty material into modern stereotypes.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 23: I like that explanation!

Hoopmanjh @@@@@26: It’s always seemed, to me, a little ambiguous how much is common knowledge at Miskatonic. I tend to think they have a fabulous and well-known collection of material on this one particular folkloric tradition… and that most people insist that it’s just the fragility of the Rare Book Room contents that makes it so difficult to get permission for a session with the Necronomicon. They can almost convince themselves…

Ruthanna @@@@@ 27 Given the human ability to ignore what one doesn’t want to see, it’s actually not that hard for the curators of the Arcane Archives to keep peeps happily ignorant. As we’ll see in “Dunwich Horror,” even the chief curator of the time, Henry Armitage, didn’t realize he was sitting on a steaming heap of nasty cosmic reality. Not until Wilbur Whateley got a bit runny on the library floor, anyhow.

Ain’t easy being the janitor at MU.

This is my first visit to this site. I’m well impressed with the

intelligent analysis and courteous exchanges here.

I’ve often wondered how Lovecraft decided to set “The Shadow Out of

Time” in the Great Sandy Desert of Australia. I’ve looked in Google Earth at

20ø 3′ 14″ South Latitude, 125ø 0′ 39″ East Longitude, and it’s just as in the

story–remote, barren, flat terrain heavily set with sand dunes. Australia,

the least geologically-active continent, was an inspired choice of a credible

place for the remains of an alien city to survive since the Cretaceous Period.

As a long-time explorer of caves, I’ve taken note of the improvement in

Lovecraft’s handling of the subterranean setting as his writing matured. In

his early stories, caves were just generic cavities that were not necessarily

set in a plausible context. In 1928, however, he visited the show cave

Endless Caverns, Virginia (recounted in his essay “A Descent to Avernus”), and

later Lookout Mountain Cave, Tennessee; from his own experience and reading,

he had learned that real caves were usually formed by water flow dissolving

limestone, and by the time he wrote At the Mountains of Madness, the realism

of its caves shows his better understanding of them. In “The Shadow Out of

Time,” in the unstable tunnels that are more ancient than most natural caves,

he has Peaslee climbing over breakdown mounds, squeezing through chokes,

leaping fissures, crawling under stalactites, walking through dusty corridors-

-just as cavers do in real caves.

But HPL never got to see as many caves as he’d have liked to. In 1934,

he got a long, enthusiastic letter from Robert E. Howard describing Howard’s

recent visit to Carlsbad Cavern. On July 28, 1934, Lovecraft replied

ruefully: “Aedepol! But how I envy you!….I’ll have to get down there some

time.” But he never did.

If Lovecraft thought Carlsbad Cavern would be impressive, he would have

been absolutely stunned by the alien qualities of Lechuguilla Cave, not far

from Carlsbad (but not yet explored in HPL’s day). I’ve often wished I could

have shown him the Chandelier Graveyard, a remote chamber in Lechuguilla. It

is decorated with conical stalagmites of selenite gypsum up to ten feet or

more high, with radiating tentacle-like arms–for all the world like statues

of the beings of the Great Race of Yith. The place could be their mausoleum.

It seems downright eerie to me that there can be a hidden, little-known but

real, feature on Earth so remarkably resembling the extraplanetary creatures

that originated only from Lovecraft’s imagination.

The climax of “Shadow”–Peaslee finding the ancient record in his own

handwriting–has occasioned a lot of (rather skeptical) thought on my part.

Handwriting is a product of a very individual brain/muscle system. Does it

make sense that the mind of a human, transplanted to a body not even part of

Earthly evolution, could possibly manipulate the tentacles of a Great Race

body to come out with the same script that Peaslee’s body would? If the mind

is a product of a particular organic structure and its unique experiences, is

it logically consistent that a human mind could be transplanted to another

human being, let alone to a body totally unhuman? It is rather like trying to

run a PC program on an Apple computer. That can be done, but requires

emulator software to interface to the different hardware. Perhaps the Great

Race’s mind exchanges could be handled in an analogous way, but since the

translation module would be foreign to both brains, it would call for a level

of bioengineering scarcely imagined today.

DGDavis @@@@@ 29 The Chandelier Graveyard would certainly have inspired HPL! And what about the hellishly hot and humid Cave of the Crystals in Naica, Mexico, with those enormous selenite crystals? Those look like they might be part of the mechanism by which the Yithians projected their minds through time and space.

I also noticed the realism of Peaslee’s scrambles over debris heaps. Merely exploring urban undergrounds, like old train tunnels, I’ve encountered daunting examples of them.

Re your observation on the handwriting: I hadn’t thought about this potential quibble, but it definitely makes sense. I do think that Yithian psychology and culture must have been heavily influenced by its succession of physical forms. Far more so than Peaslee, since the Yithians exist in a given once-alien species much, much longer than he existed in cone-form. Yet he, too, adapted to a certain extent.

AMPillsworth @@@@@ 28: The janitors know everything.

DGDavis @@@@@ 29: Welcome! And interesting background on the caves–not an experience I’ve had yet myself, so I hadn’t noticed the improvements in his portrayals. I hope that unlike HP, I can get around to my own subterranean explorations one of these days.

I’m extremely skeptical of the handwriting myself–that’s muscle memory as much as brain, though the distinction wasn’t well-understood when he was writing. We won’t even talk about the level of disbelief that needs suspending to switch minds sans brains. It’s an awesome plot device, so there is my disbelief, swinging cheerfully from the ceiling.

AMPillsworth @@@@@ 30: Having left my disbelief suspended but retrieving a little of the neuropsychological expertise that feeds it, Yithian embodied cognition is kind of fascinating. I want to corner one of their cognitive scientists and talk about doing some *real* longitudinal studies.

Thank you so much for writing these entries. HP Lovecraft’s work doesn’t get as much in-depth critical analysis compared to some other authors, so it’s very interesting to see the two of you exploring this.

The Shadow Out of Time is one of his strongest (perhaps the strongest) work for many of the reasons you outlined. It is interesting to see it as both an expression of his xenophobia (the fundamental fear of the unknown) and his fascination with the same (which even might tie into this story coming across as less overtly racist than his earlier work).

A recent comic adaptation took an interesting approach with this. In Yithian times, Peasless meets Yiang-Li, a philsopher from a far future (and apparently “cruel”) China. Yiang-Li is only mentioned once in the original story, but the comic actually expands on his role. Yiang-Li mentions that he misses his daughter (I don’t recall if the comic book Peaslee says the same about his children), and becomes the closest thing Peaslee has to a friend. It’s one of the few diversions from the original text, and actually quite an interesting one.

Also, and I apologize for being so nitpicky, but aren’t the Elder Things different from the flying polyps? I thought the Elder Things built the Antarctic city and created the shoggoths. It’s been a while since I read the original story, and I know Lovecraft sometimes used terms interchangeably.

@32: You are right, the Elder Things and flying polyps are different species.

Lovecraft wasn’t much of a future historian but there seems to be another reference to the empire of “Chan Tsan” in “Beyond the Wall of Sleep”. I wonder if anyone set a story there…

This story shows that clearly, Code Quantum didn’t insist nearly enough on the fate of those who spent some time in Sam Beckett’s body.

@29: Good remark on the handwriting, especially considering that the Yith that exchanges his body with Peaslee has to learn how to use his new muscles: it’s not nitpicking if the author had thought of this aspect and then forgets it mid-story.

I’m trying to improve my lovecraftian vocabulary in this reread. This is apparently the definition of megathic: “word used in Lovecraft’s The Shadow Out of Time“. Remark that the library only becomes Cyclopean when it is seen from a human body. The word seems to have a very specific meaning to Lovecraft, it doesn’t just describes the size but how abnormal the size is.

I see this story as a celebration of life. I think it’s wonderful that so many different species spread out through the solar system, and though Lovecraft tries his best, I can’t see the horror of the insignificance of humanity. I can’t understand why the protagonist is constantly feeling dread rather than awe. I came to the same conclusion as birgit (17): just imagine how different that story would read if you replace Nathaniel Peaslee with Carl Sagan: he gets the chance to live among aliens, to converse with people from other times, species and planets and to discover their culture and their science (which is much more advanced than what was previously thought), he discovers that we are not going to destroy ourselves (or at least not for thousands of years) and that when we do become extinct, other civilisations will take our place… And when he comes back to Earth, he is able to find proof that what he experienced was real (the Cyclopean blocks are proof enough or me, and there’s no reason he would have lost the book had he not panicked). I want to see that episode of Cosmos!

@34: Wasn’t it the case in Quantum Leap that Sam kept his own body but had an “aura” to make him look like the person he replaced?

I think “megathic” might be a typo: it’s “megalithic” in the version I read.

I’m in agreement with the perspective that “The Shadow Out of Time” is only really a horror story from the viewpoint of this protagonist. Someone more open-minded might just have been tempted to feel that the idea that “life goes on” is an unusually upbeat notion for a Lovecraft story. It makes me wonder what Lovecraft would have been like in Campbell’s Astounding…

SchuylerH@33: yeah, it’s just that he refers to the polyps as “elder things” (lower case) in story, which might cause confusion.

(I had quite failed to recall the “ruled over 3 other planets” bit. Wonder what happened to those elsewhere than Earth?)

Whatever happens to humanity doesn’t sound so good: “I…trembled at the menaces the future may bring forth. What was hinted in the speech of post-human entities of the fate of mankind produced such an effect on me that I will not set it down here.” And since the last mention of humanity seems to refer to 14,000 years ahead and the “Dark Conquerors”, it doesn’t seem like humanity is very long-lasting by the standards of Elder Beings. (Of course, we have a narrator with definite quirks: perhaps “humanity turns into a race of ascended cyborgs wizard-monsters and migrates to interstellar space” would be worse to him than simple extinction).

Z. Miller@32, I wonder if the “Cruel Empire of Tsan-Chan” is a callback to this scene from 1925s “He”…

“For full three seconds I could glimpse that pandemoniac sight, and in those seconds I saw a vista which will ever afterward torment me in dreams. I saw the heavens verminous with strange flying things, and beneath them a hellish black city of giant stone terraces with impious pyramids flung savagely to the moon, and devil-lights burning from unnumbered windows. And swarming loathsomely on aerial galleries I saw the yellow, squint-eyed people of that city, robed horribly in orange and red, and dancing insanely to the pounding of fevered kettle-drums, the clatter of obscene crotala, and the maniacal moaning of muted horns whose ceaseless dirges rose and fell undulantly like the wave of an unhallowed ocean of bitumen.”

SchuylerH @@@@@ 35: It reminds me of the Evolving Planet exhibit at Chicago’s Field Museum. They have all their display fossils in chronological order, and every couple of rooms you come across a huge stripe across the floor labeled: MASS EXTINCTION. And then… life goes on, often in wildly different form. Awe-inspiring in all senses of the word.

And of course, it’s no great surprise what’s at the end of the exhibit…

I’m enjoying these articles on the Lovecraft reread. Finally finished Shadow tonight for the first time, and found it fascinating. Not as much horror related, but more sci-fi/adventure to me.

After reading through the comments, I’ve tried to think how I would react to the scenario. To be given the opportunity to visit that library sounds so tempting, but to put my family through who knows how much time as a completely different person? That’s an interesting choice to me, and one that I’m not sure has a correct answer.

Heath Nantz @@@@@ 38 Yes, that problem with a multi-year disruption of relationships and employment is a big stumbling block to accepting the Yithian invitation. Probably why it’s not actually an invitation.

Z. Miller @@@@@ 32: There is some confusion about who and what are the real Elder Things. We can call the cones Yithians or Yith and the crabby fungi Mi-Go, but the Antarctic race? I don’t think we ever get a planet of origin or a good folk name for them. Myself, I call the polyps polyps and the other Elder Things, um, those star-headed radiate thingies.

Star-Headed Radiates is so the name of my next goth rock band.

R. Emrys @@@@@ 37 What if you stepped on the MASS EXTINCTION marker and it extincted your mass, leaving you pure energy? To the plot bunny hutch with you!

Hmm, I bet the last thing in the exhibit is the Great Beetle-Bug race! Though when I think of the last life on earth, I’m reminded of the terrifying scene at the end of Wells’ Time Machine, where the traveller finds himself on a red-lit beach, watching some anomalous thing flop in the water of a bloody receding tide. Makes me want to cry every time.

Somewhat off-topic, but recall the somewhat problematic remark of S.T. Joshi on an earlier page? Yes, he apparently is a bit of an asshat.

http://www.stjoshi.org/news.html (August 16th entry)

BMunro @@@@@ 41: Oh, dear.

My first thought was that there wasn’t much of substance to engage with in Joshi’s trolling… but then I started thinking about Butler’s genre qualifications, and the comparisons between her and Lovecraft are actually quite intriguing. Both wrote stories mixing both SFnal and fantasy tropes–canonically, in fact, much of Lovecraft is overt science fiction even though the intended effect is horror. Both take put an SF gloss on… mind switches, body horror, immortality, time travel, deeply disturbing ancestors that one would rather not think about… And then Butler asks: after you feel that revulsion, how do you get to empathy?

BMunro @@@@@ 41 About who should have the honor of being the disembodied head atop the World Fantasy statuette. Much as I love HPL, I think it would be best for the statuette to be more generic — with so many great fantasists past and present, picking one to please all is impossible.

Of course, we’d then have a fight about what generic object to put on the award: a dragon, a unicorn, GRRM’s hat, etc.

I am surprised that no one has yet mentioned the Darkest of the Hillside Thickets adaptation of this story as a concept album entitled the Shadow out of Tim. It was quite well done.

Hi, an Australian here.

On the use of the term “blackfella” (and I am the LAST person to give Lovecraft any credit when it comes to race) it is honestly a fairly neutral phrase over here when describing Indiginous Australians. In fact it is most often self descriptive amoung indiginous people and no white Australians object to the use of the term “whitefella” which is also common. I wouldn’t recommend if you visit Austalia calling a indiginous Australian that, but more for the same reason I wouldn’t recommend a white person calling an African-American woman “sister”. Unless you’re good friends with them it’s a bit tacky. But to be fair I’ve not read the story itself and I’m really wary about the context Lovecraft may have put it in.

Robert Silverberg has written quite eloquently about the impact that this tale had on him:

“The key passage, for me, lay in the fourth chapter, in which Lovecraft conjured up an unforgettable vision of giant alien beings moving about in a weird library full of “horrible annals of other worlds and other universes, and of stirrings of formless life outside all universes. There were records of strange orders of beings which had peopled the world in forgotten pasts, and frightful chronicles of grotesque-bodied intelligences which would people it millions of years after the death of the last human being.”

I wanted passionately to explore that library myself. I knew I could not: I would know no more of the furry prehuman Hyperborean worshippers of Tsathoggua and the wholly abominable Tcho-Tchos than Lovecraft chose to tell me, nor would I talk with the mind of Yiang-Li, the philosopher from the cruel empire of Tsan-Chan, which is to come in AD 5000, nor with the mind of the king of Lomar who ruled that terrible polar land one hundred thousand years before the squat, yellow Inutos came from the west to engulf it. But I read that page of Lovecraft ten thousand times—it is page 429 of the Wollheim anthology, page 56 of the new edition—and even now, scanning it this morning, it stirs in me the quixotic hunger to find and absorb all the science fiction in the world, every word of it, so that I might begin to know these mysteries of the lost imaginary kingdoms of time past and time future.”

As far as HPL “coming to terms with racism”, part of the horror in this story is that there is nothing superior about white people. As of the year AD 6930, Chinese will rule and their elites will be at least as “racist” / “cruel” as Lovecraft ever was. Also like 1930s America, this will be mitigated in Tsan-Chan by decent folk like Yiang Li.

By the way I’ve recently discovered a SF series about Tsan-Chan – although the author doesn’t call it that. It is Chung Kuo by David Wingrove.

As a relative newcomer to the Tor archives I am a bit late to the table, but as an HPL fan I have been eagerly reading this sequence revisiting his tales

When I got to this line I scared my poor cat I laughed so loud

“An exchange with the Yith has the same appeal as jumping into the TARDIS: it may destroy your life and your sanity, but…”

This so closely parallels my own feelings about this particular tale ;-)

I have little to add to the wonderfully varied and witty commentaries both in the articles and below, so I will content myself with belated thanks for the wealth of insights and the lovely feeling of community I have found here.

There seems to be general agreement that this is one Lovercraftian horror we would all love to experience. Kidnapping by the Great Race sounds like – fun, like something you could really enjoy.

Slywlf @@@@@ 48: Welcome–glad you’re enjoying!

This is not one of my favourites. I find it too boring that the entire plot hinges upon the protagonist finally discovering or confirming what he’s been telling us quite plainly almost from the beginning of the account. The reader has already worked out what’s going on, from his own narrative, ages before he does. He must be in some serious denial. There’s no surprise when realisation comes, which removes a great deal of the suspense and horror that Lovecraft expertly weaves into many of his other tales.

That said, I get the whole “world-building” aspect, and I actually do enjoy that HPL references some of his other works in this one. I love when authors do that. I keep telling my wife that Jane Austen’s biggest weakness is that none of the characters in any of her stories ever reference the characters or events from her others.

Still, there are some particular problems with ‘The Shadow’ which bother me a bit.

Firstly, for a mind-swap that’s supposed to end with a ‘Men In Black’-style memory-wipe at the human side (which would make for a much more boring tale I admit), it seems to me that far too much information, with a surprising amount of detail, has managed to leak out into an easily-obtainable form which doesn’t take the protagonist too much effort to uncover. You’d think the so-called Great Race would have perfected their technique after all these aeons.

I’m also irritated that he is able to observe from his memory-dreams that the cone-shaped creatures are *ten feet tall* and that he is frightened by the immense size of the furniture. How can he possibly know what *ten feet tall* looks like when there are no regular five-to-six feet tall humans standing around to compare them with? Also, why is he frightened by the size of the furniture when the furniture has been built for the very creatures of which his mind is currently occupying? All the furniture should appear perfectly normal to him.

I do think it’s rather fun that Prof. William Dyer appears in this tale, and he seems to be keeping rather tight-lipped about his experiences in Antarctica, as you might expect. However, you’d think he’d be well and truly over exploring eldritch ruins in desolate places after what happened to him and Danforth. He did previously state:

So what happened, Dyer? Did you change your mind? Or did a Yith change it for you, eh?

Say, did anyone else catch this quote:

On my first reading, before I learned about the mind-swap, I thought this line might be suggesting that between 1908-1913 he was actually the protagonist of ‘The Nameless City’! 1911 is the same year that Lord Dunsany’s ‘The Probable Adventure of Three Literary Men’, referred to in the tale, was published, so it’s possible. But, once you discover that a Yith was controlling his mind during that time, it blows the theory out of the water, for why would a Yith be at all surprised or disturbed at the idea of discovering a pre-human city?

Also, I have since discovered that the protagonist of ‘The Nameless City’ is more likely to be Lord Northam from ‘The Descendant’.

Ruthanna, didn’t you end up identifying the Great Race with the Antarctic shoggoth-making Elder Things for Winter Tide? That was a bit odd to me.

Damien @@@@@ 52: Not “identifying with” so much as deciding that the Yith took the Elder Things over partway through their history. I needed the Yith to arrive on Earth earlier than they did canonically because of Reasons which were mostly thematic at the time, but which seem to be resulting in actual plot in the third book. But yeah, I make no pretensions that my timeline isn’t odd, or doesn’t occasionally play fast and loose with canon.

(The Litany of Earth–the Aeonist canon rather than my story of the same name–does call the Elder Things “faces of the Yith” rather than “part-time faces of the Yith.” This is because the Yith dictated the Litany, and it glosses over some things.)

Ruthanna: Cool, thanks!

Hey, piggybacking to ask another question:

So your series is largely about reclaiming Lovecraft’s “races” from Lovecraft’s xenophobia. Sympathetic view of the Deep Ones, rootless cosmopolitan Mi-Go, and of course being kinder to the diversity of actual humans. Yith are terrifying or just appalling to think about too closely but one can kind of work with them. (And any Yith you meet by definition has been doing non-consensual stuff, so a dim view of them is justified by their actions.)

But when it comes to the people of the rock, the xenophobia and blood taint tropes seem fully justified. You don’t want to meet one, you don’t want to learn you’re descended from one, yes the characters come up with a treatment but it’s still something to be treated. Madness really is in their blood. Having a personal crisis because you’re part black or Welsh is silly, having a crisis because you’re part K’n-yan is perfectly reasonable.

I guess I don’t have a specific verbalizable question, but it seemed an interesting contrast. “Racism is bad. Except for *those people*.”

That is how both the Deep Ones and the Yith see the K’n-yan. There’s a little more nuance in Deep Roots, I think/hope. But my own take on them is more along the lines of: there are ideas and belief sets you can take on that are bad for you and bad for everyone around you, and the K’n-yan have hit on a particularly egregious set. If you bump into a K’n-yan who’s been raised among other K’n-yan, the odds that they’ll see you as a person, and not as an interesting source of entertainment or experimental material, are not good. And because it’s cosmic horror, they’ve managed to enforce these attitudes not just through the usual cultural routes, but through magical studies that change how they and their children perceive the world, and that are even harder to shake than ordinary prejudice.

Audrey doesn’t have the K’n-yan upbringing, but does have some additional weirdness from the ways her ancestors were used as experimental material. More on that in Deep Roots as well…

I don’t see why. If you admit the possibility of mass mind transfer, what’s stopping a mere re-engineering of the host organism’s genome to produce compatible cerebral (or equivalent) tissue?

<em>Cone-form Yithians have cone-form genes, right? Once projected from their ur-forms, wouldn’t Yithians be unable to spawn NEW Yithians?</em>

But the next generation of cone creatures would be raised as Yithians and would possess Yithian culture and mentality – perhaps that’s what the Yith really care about. Through that lens, the Yith aren’t a species, but an ongoing body of knowledge and practice that destroys and assimilates species to keep itself going. Sort of personifications of the Cthulhu Mythos itself.

Even the cone-form Yithians aren’t the original Yithians — they’re just the latest in a series of species that have been hijacked.

Yith is the ultimate expression of meme culture.

For a culture that periodically picks up and leaves everything behind they place a lot of emphasis on the written word. How do the beetles get the yithian archives?

Daniel @@@@@ 60: Dig ’em up, I assume. Having already created backups for Peaslea’s displaced journals, because time travel.