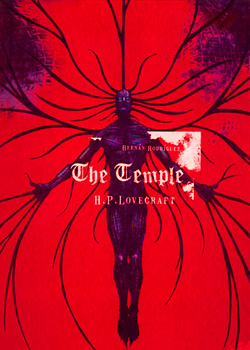

Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at “The Temple,” written in 1920 and first published in the September 1925 issue of Weird Tales. You can read the story here. Spoilers ahead.

Summary: This narrative is a manuscript found in a bottle on the Yucatancoast. Its author introduces himself at proud length as Karl Heinrich, Graf (Count) von Altberg-Ehrenstein, Lt. Commander of the Imperial German Navy, in charge of the submarine U-29. He’s equally exact with the date—August 20, 1917—but cannot give his exact coordinates. This sad lapse from German precision is due to a series of strange calamities.

After the U-29 torpedoes a British freighter and sinks its lifeboats, one of the dead is found clinging to the sub’s railing. Karl notes his dark good looks and supposes he was an Italian or Greek who unfortunately allied himself with “English pig-dogs.” Karl’s lieutenant, Klenze, relieves a crewman of the ivory carving he’s looted from the dead man. It represents the head of a laurel-crowned youth and impresses the officers with its antiquity and artistry.

As the crew tosses the corpse overboard, they jar open its eyes. Old Mueller even claims that the corpse swam away. The officers reprimand the crew for these displays of fear and “peasant ignorance.”

Next morning some crewmen wake from nightmares dazed and sick. An uncharted southward current appears. Mueller babbles that the U-29’s victims are staring through the portholes. A whipping silences him, but two of the sick men go violently insane and “drastic steps” are taken. Mueller and another man disappear—they must have jumped overboard unseen, driven to suicide by their delusions. Karl supposes these incidents are due to the strain of their long voyage. Even Klenze chafes at trifles, like the dolphins that now dog the sub.

The U-29 is heading for home when an unaccountable explosion disables the engine room. The sub drifts south, escorted by the dolphins. When an American warship is spotted, a crewman urges surrender and is shot for his cowardice. The U-29 submerges to avoid the warship, and is unable to surface. Full-scale mutiny erupts, the crew screaming about the “cursed” ivory head and destroying vital equipment. Klenze is stunned, but Karl dispatches them with his trusty sidearm.

At the whim of the southward current, the U-29 continues to sink. Klenze takes to drinking and overwrought remorse for their victims. Karl, however, retains his Prussian stoicism and scientific zeal, studying the marine fauna and flora as they descend. He’s intrigued by the dolphins, which don’t surface for air, or depart when the water pressure grows too great. Death seems unavoidable, but Karl is comforted to think the Fatherland will revere his memory.

They approach the ocean floor. Klenze spies irregularities he claims are sunken ships and carven ruins. Then he tries to exit the sub with Karl in tow, shrieking that “He is calling!” While he still addresses them with mercy, they must go forth and be forgiven. To remain sane and defy him will only lead to condemnation.

Realizing Klenze is now a danger, Karl allows him to exit the sub. Swarming dolphins obscure his fate.

Alone, Karl regrets the loss of his last comrade and the ivory carving Klenze refused to give up. The memory of that laurel-crowned head haunts him.

The next day he ascends the conning tower and is amazed to see that the U-29 approaches a sunken city. The southward current fails. The dolphins depart. The U-29 settles atop a ridge; an enormous edifice hollowed from solid rock rises beside it, close at hand.

It appears to be a temple, “untarnished and inviolate in the endless night and silence of an ocean chasm.” Around the massive door are columns and a frieze sculpted with pastoral scenes and processions in adoration of a radiant young god. Inexpressibly beautiful, the art seems the ideal ancestor of Greece’s classical glory.

In a diving suit, Karl explores. He plans to enter the temple but can’t recharge the suit’s light. A few steps into the dark interior are all he dares to take. For the first time, dread wars with curiosity. Karl broods in the dark submarine, conserving what’s left of his electricity. He wonders if Klenze was right, that Karl courts a terrible end by refusing his call. He also realizes that the ivory head and the radiant god of the temple are the same!

Karl takes a sedative to bolster his shaken nerves. He dreams of the cries of the drowning and dead faces pressed against the porthole glass. They include the living, mocking face of the seaman who carried the ivory head.

He wakes with a compulsion to enter the temple. Delusions plague him—he sees phosphorescent light seeping through the portholes and hears voices chanting. From the conning tower, he sees “the doors and windows of the undersea temple…vividly aglow with a flickering radiance, as from a mighty altar-flame far within.” The chanting sounds again. He makes out objects and movement within, visions too extravagant to relate.

Though Karl knows he’s deluded, he must yield to compulsion. Nevertheless he will die calmly, “like a German.” He prepares his diving suit. Klenze couldn’t have been right. That can’t be daemonical laughter. Let him release his bottled chronicle to the vagaries of the sea and “walk boldly up the steps into that primal shrine, that silent secret of unfathomed waters and uncounted years.”

The rest, dear reader, must be conjecture.

What’s Cyclopean: Folks who’ve been wondering where the thesaurus went: it’s here. The temple is “great,” “titanic,” and “of immense magnitude,” but not at all cyclopean. We get some aqueous abysses and aeon-forgotten ways, but the language is shockingly—but effectively—straightforward.

The Degenerate Dutch: Germans apparently can’t keep a crew in line without murder and regular threats of same. And show off their villainy by using racist epithets and insults against everyone else and each other—one quickly loses track of who’s a pig-dog, who an Alsatian swine, a swine-hound, or a soft, womanish Rheinlander. This would be a more effective technique used by pretty much any other author ever in the history of authors.

Mythos Making: Not much mythos here, although the hints about the radiant god are intriguing. Some have suggested that the sunken city may in fact be R’lyeh, but the architectural aesthetic really doesn’t fit.

Libronomicon: There are books in the submarine, but we don’t get much detail about them and one suspects they’re never retrieved for storage in the Miskatonic library.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Near the beginning two crew members become “violently insane” and are cast overboard. Not healthy to go mad on this boat. Klenze becomes “notably unbalanced” after the narrator shoots the entire remaining crew. Y’think? Then he goes “wholly mad” and leaves through the airlock. At the end, the narrator is delightfully calm about explaining that he’s now mad himself, and it’s a pity that no proper German psychiatrist can examine his case because it’s probably very interesting.

Anne’s Comments

What’s one to think of Karl Heinrich, Graf von Altberg-Ehrenstein, Lt. Commander of the Imperial German Navy, et cetera? I expect that the satirical aspects of his characterization would have been grimly amusing to an audience just a couple years clear of World War I. He’s not any old German, after all. He’s a Prussian nobleman, hence entitled by his superior Kultur to look down not only on British pig-dogs but on lesser Germans, like that Alsatian swine Mueller and that womanish Rhinelander Klenze. Chauvinist much, except, of course, Chauvin was one of those French pig-dogs.

Like any good B-movie German officer, whether a follower of the Kaiser or the Fuehrer, Karl is a man of much zeal and little sympathy, icily rational, quick to punish any faltering, utterly certain of the justness of his cause. He lets the crew of the British freighter leave in life boats but only so he can get good footage for the admiralty records. Then it’s bye-bye, lifeboats. Most of his own crew die courtesy of his pistol; one imagines he’d feel worse about putting down rabid Rottweilers. When he expels Klenze into the sea, he rushes to the conning tower to see whether the water pressure will flatten his former comrade, as it theoretically ought. Guys, he’s simply not given to emotion. He’s says so himself, proud as ever of his totes Teutonic self. Dialing down his Red Skull flamboyance a notch or two, Hugo Weaving could play Karl with aplomb.

In as much as Lovecraft is having fun with Karl, the irony is obvious. Racism, nationalism, regionalism, they don’t play so well when it’s the opponent, the Other, practicing them.

But is there more to Karl than satire? Is “Temple” a straightforward tale of the villain getting what’s coming to him, and not only from his victims but from European civilization itself, the Hellenistic tradition personified in a proto-Hellenistic god, laurel-crowned?

Maybe. Maybe not. My inner casting agent can also see Karl played by Viggo Mortensen, with tiny cracks in his iron German will and an increasingly frequent waver to his steely German glare. Though Lovecraft’s conceit is that Karl writes out his entire narrative just before he exits the sub for the last time, to me it reads more like excerpts from a journal written over the two months of his descent into the watery unknown. It starts with a certain bravado and a recitation of the facts, and how they show that Karl was not to blame for the U-29’s misfortunes. Gradually he seems to write less for official eyes and more for himself, to account for his personal impressions and feelings. Yes, feelings, because Karl’s not immune to emotion after all. He admits that he misses Klenze, mere Rhinelander that he was. He stands astonished at his first sight of sunken “Atlantis” and only afterwards dispels some of the wonder by recalling that, hey, lands do rise and fall over the eons, no biggie, I knew that. He owns to fear, the more unworthy in that it arises not from his physical plight but from superstitious dread.

And there are earlier hints that Karl is not purely the Prussian Ironman he wishes to appear. Looking at the dead seaman from the British freighter, he notes that “the poor fellow” is young and very handsome, and that he’s probably Italian or Greek (son of ancient Romeand Athens!) seems a point in his favor. Later, alone with Klenze, he leads the lieutenant to “weave fanciful stories of the lost and forgotten things under the sea.” Karl represents this as a “psychological experiment,” but I suspect he took a less distant interest in Klenze’s meanderings—and perhaps some of the comfort all humans derive from tales told ’round the fire.

In the end Karl is a classic Lovecraft narrator, devoted to scholarship and reason and science, wary of superstition and legend, a modern man. Then comes the fall, into horror and wonder. Then comes the call, to embrace the “uns:” the unthinkable, unnamable, unexpected, unfathomable, uncounted, UNKNOWN.

And Karl does. He goes into the temple. The conceit of the narrative, a missive sent before the end, precludes Lovecraft from following him inside, and that’s all right. The story concludes in the reader’s mind, whether in uncertainty embraced, or in terrible retribution or twisted redemption imagined.

Last thoughts on this one: Where does it stand in the Lovecraft canon? I count it as a proto-Mythos story, though there are no direct references to Mythos creatures or lore. The trappings are actually more Dunsanian/Dreamlandish, but the tone and theme are more Mythosian: Reason meets Weird; Reason blown. Then there’s the idea of underwater cities, underwater humanoids, the sunken temple with a calling god. As the art of Karl’s inundated fane could be called an anticipation of Greece, these aspects of “Temple” could be considered anticipations of “Call of Cthulhu” and “Shadow Over Innsmouth,” little premonitory shivers.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

After reading a certain amount of Mythos fiction, one grows a bit inured to overt grotesquerie. One comes to expect ancient ruins to be fairly caked with monstrosities engaged in unspeakable, perhaps incomprehensible activities—for the deeply horrifying to show its nature plainly on the surface.

The radiant god of The Temple is particularly effective against the backdrop of these expectations: familiar and even comforting in form, offering light in the ocean’s alien depths—he just makes you want to step outside and bath in his glory, doesn’t he? *shiver*

The lack of grotesquerie here makes the moments of strangeness more effective—the dolphin escort that never needs to breathe, for example, is still kind of freaking me out. (One of these days dolphins and humans really need to get together and share their horror stories about each other’s realms.) The bridges over a long-drowned river show the existential threat of aeons passing better than explicit statements about how dreadful someone finds ancient architecture.

I’ve been through the U-boat at Chicago’s Museumof Scienceand Industry, and would be an easy sell on one as a setting for—or maybe a monster in—a Lovecraft story. So it’s a pity that the U-boat and its crew are the big weakness in this story. Just post-World-War-I, the narrator’s caricatured German nationalism probably wouldn’t stand out against the usual run of propaganda posters. But I was kind of relieved—as crew-men were variously murdered, killed by exploding engines, or drawn into the depths by inhuman temptation—that there were fewer people for him to make obnoxious comments about. Trying to make a character unsympathetic through a tendency towards racist rhetoric… is a little weird, coming from Lovecraft.

In fact, I’m not a hundred percent sure the narrator is supposed to be quite as obnoxious as he is. I’m not sure Lovecraft is sure, either. He’s on record elsewhere admiring the Nordic strengths of determination and willingness to take action—and the narrator has these in spades. Is this over-the-top stereotype intended to be mockery, parody, or some warped role model of intended manliness in a fallen enemy?

The narrator’s ill-fated brother officer, Klenze, seems much more like the usual Lovecraftian protagonist in his nerves, self-doubt, and proneness to supernatural speculation. Even when the narrator thinks he’s going mad, by contrast, he’s still matter-of-fact and confident in this judgment. Once alone, he’s actually better company—and the spare descriptions of his solitude become increasingly compelling.

The light grows in the temple—a lovely, minimal detail, that implies all the horror necessary.

“This daemoniac laughter which I hear as I write comes only from my own weakening brain. So I will carefully don my diving suit and walk boldly up the steps into that primal shrine; that silent secret of unfathomed waters and uncounted years.”

Whew.

Join us next week for a little night music with Erich Zann.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available June 24, 2014 from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She currently lives in a somewhat chaotic old manor house outside of Washington, DC.