Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories. Today we’re looking at “The Festival,” written in October 1923 and published in the January 1925 issue of Weird Tales. You can read the story here. Spoilers ahead.

Summary: Our narrator is far from home, approaching the ancient town to which his family’s ancient writings have called him for a festival held once a century. It’s Yuletide, which in truth is older than Christmas, older than mankind itself. Our narrator’s people are also old. They came from South America long ago, but scattered, retaining rituals for which no one living still understands the mysteries.

He’s the only one who’s come back tonight—no one else remembers. He reaches Kingsport, a snow-covered New England town full of “ancient” colonial buildings, with the church on the central hill untouched by time. Four of his kinsmen were hanged for witchcraft here in 1692, but he doesn’t know where they’re buried.

The town is silent—none of the sounds of merriment one might expect on Christmas Eve. He has maps, though, and knows where to go. He walks—they must have lied in Arkham about the trolley running here since there are no wires.

He finds the house. He’s afraid, and the fear grows worse when no footsteps precede the answer to his knock. But the old man in a dressing gown seems comfortingly harmless. He’s mute, but carries a wax tablet on which he pens a greeting.

The old man (but not, in spite of the setting, the Terrible Old Man) beckons him into a candle-lit room. An old woman spins beside the fireplace. There’s no fire and it seems damp. A high-backed settle faces the windows; it seems occupied though the narrator isn’t sure. He feels afraid again—moreso when he realizes that the man’s eyes never move and his skin appears made of wax. A mask? The man writes that they must wait, and seats him by a table with a pile of books.

And not just any books, but 16th and 17th century esoterica including a Necronomicon, which he’s never seen but of which he’s heard terrible things. He flips through it (Wouldn’t you?) and gets absorbed in a legend “too disturbing for sanity or consciousness.” (It really does make a great coffee table book; your guests will be thoroughly distracted. Though their conversation later may get a little odd.)

He hears the window by the settle close, and a strange whirring, and then it no longer feels like someone’s sitting there. At 11, the old man leads the narrator out into the snow. Cloaked figures pour silently from every doorway and process through the streets.

Fellow celebrants jostle him. Their limbs and torsos seem unnaturally pulpy and soft. No one speaks or shows their face as they head for the church on the central hill. The narrator hangs back and enters last. Turning back before he goes in, he shudders—there are no footprints in the snow, not even his own.

He follows the crowd into the vaults beneath the church, then down a staircase hidden in a tomb. The footfalls of those ahead make no sound. They come out in a deep cavern shimmering with pale light. Someone’s playing a thin, whining flute, and a wide oily river flows beside a fungous shore. A column of sick, greenish flame lights the scene.

The crowd gathers around the flaming column and performs the Yule rite “older than man and fated to survive him.” Something amorphous squats beyond the light, playing the flute. He hears fluttering. The old man stands beside the flame, holding up the Necronomicon, and the crowd grovels. Our narrator does the same, though he’s sick and afraid.

At a signal the music from the flute changes. Out of the darkness comes a horde of tame winged things: not quite like crows, nor moles, nor buzzards, nor ants, nor bats, nor decomposed human beings.

Celebrants seize and mount them, one by one, and fly away down the subterranean river. The narrator hangs back until only he and the old man remain. The man writes that he’s the true deputy of their forefathers, and that the most secret mysteries are yet to be performed. He shows a seal ring and a watch, both with the family arms, to prove it. The narrator recognizes the watch from family papers; it was buried with his great-great-great-great-grandfather in 1698.

The old man pulls back his hood and points to their family resemblance, but the narrator is sure now that it’s only a mask. The flopping animals are getting restless. When the old man reaches out to steady one he dislodges the mask, and what the narrator sees causes him to throw himself, screaming, into the putrescent river.

At the hospital they tell him that he was found half frozen in the harbor, clinging to a spar. Footprints show that he took a wrong turn on his way to Kingsport and fell off a cliff. Outside, only about one in five roofs look ancient, and trolleys and motors run through a perfectly modern town. He’s horrified to learn that the hospital is on the central hill, where once the old church stood. They send him to Saint Mary’s in Arkham, where he’s able to check the university’s Necronomicon. The chapter he recalls reading is, indeed, real. Where he saw it is best forgotten.

He’s willing to quote only one paragraph from Alhazred: it warns that where a wizard is buried, his body “fats and instructs the very worm that gnaws, till out of corruption horrid life springs, and the dull scavengers of earth wax crafty to vex it and swell monstrous to plague it. Great holes secretly are digged where earth’s pores ought to suffice, and things have learnt to walk that ought to crawl.”

What’s Cyclopean: Nothing’s cyclopean, but this is still a festival of adjectives, of which “the putrescent juice of the earth’s inner horrors” may be the purplest, although “that unhallowed Erebus of titan toadstools, leprous fire, and slimy water” is also pretty impressive.

The Degenerate Dutch: The narrator describes his ancestors as “dark furtive folk from opiate southern gardens of orchids,” though these South American origins are basically forgotten for the entire rest of the story.

Mythos Making: We get Kingsport here, and the Necronomicon, but connections to Mythos canon are a bit tenuous.

Libronomicon: In the house where the narrator waits, coffee table books include Morryster’s Marvells of Science, Joseph Glanvill’s Saducismus Triumphatus, Remigius’s Daemonolatreia, and “the unmentionable Necronomicon of the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred, in Olaus Wormius’ forbidden Latin translation.” None of which ought to be left lying around in a damp room, given that they’re editions from the 1500s and 1600s. That’s worse than Yithian marginalia, which at least have historic (and prophetic) interest.

Madness Takes Its Toll: At Saint Mary’s in Arkham, they know how to properly treat cases of exposure to eldritch horror.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Okay, call me slow—on previous readings I didn’t get the ending, parsing the Necronomicon quote as basically, “there are nasty things below the earth.” Yeah, thanks, tell me something I don’t know. This time I get it: his witchy ancestors are all dead, and the worms who fed on their bodies now carry on their traditions—or a twisted mockery thereof. Ew. That may be the… grossest… metaphor for cultural appropriation that I’ve ever encountered. Kind of a pity Lovecraft didn’t intend it that way.

Or maybe he did, though not in the way we tend to think about it nowadays—it’s not un-Lovecraft-ish to suggest that once-proud traditions are now carried out in degenerate form by those not worthy of them. And the seemingly kinda random opening quote suggests he knew what he was playing with here. Not being a Latin expert myself, I did a quick search and found this nifty discussion. In brief, the quote translates as: “Demons have the ability to cause people to see things that do not exist as if they did exist.” It’s ostensibly Lactantius, but the direct quote is actually from Cotton Mather. Cotton was quoting his dad, Increase Mather, who used it as an epigram for his book Cases of Conscience. Increase’s “quote” is a paraphrase of Nicolaus Remigius’ Daemonolatreia, which in turn paraphrases a longer and less directly-stated passage from Lactantius.

And given that the Daemonolatreia shows up amongst the World’s Worst Coffee Table Books, that’s probably not an accident. By the time the pure traditions of Christian Rome get to New England, they’re almost unrecognizable—but still presented as the unaltered wisdom of your forefathers. So Lovecraft may not be worried about other people taking over his ancestors’ traditions, but perhaps New England is to the Roman Empire as unholy worms are to our narrator’s all-but-forgotten familial rites. Huh.

On a different note, I’d forgotten that the narrator is ostensibly of indigenous South American ancestry. This is probably because it plays exactly no role in the story. The ancient rites center around Kingsport, the narrator has heard of the Necronomicon, his family puts coats of arms on seal rings and watches, and in general everything seems considerably less pluralistic than your average Cthulhu cult. The narrator’s increasing freak-outedness never comes across as “I don’t think this is what my forefathers were actually doing.” His motivations don’t match his supposed background, and he swiftly transforms into a standard Lovecraft protagonist fleeing the strange because it’s strange. Though I appreciate the story’s creepiness, it doesn’t really have the courage of its set-up.

Finally, let’s talk about Kingsport. Kingsport is the outlier in Lovecraft Country. Arkham and Dunwich and Innsmouth all have distinct personalities, and each instantly brings to mind a particular flavor of eldritch. But what’s in Kingsport? The Terrible Old Man protects it from thieves with dark poetic justice, or perhaps he lives in a Strange High House with a view of the abyssal mist. Ephraim-as-Asenath goes to school there. In “Festival,” we have a maybe-alternate-maybe-illusory town of wizard-eating worms. It’s not that these are incompatible, but they don’t add up to a clear picture either. Kingsport seems more surreal than its neighbors, and if you dare travel there repeatedly, there’s no predicting what will happen..

Anne’s Commentary

As the epigraph from Lacantius says, demons are tricky creatures, always making us silly humans see things that aren’t there. The way I read it, this tenth or twelfth time, the narrator may never actually descend the great ridge that separates Arkham and Kingsport. Instead, according to the evidence of snow-recorded footprints, he pauses on Orange Point, in sight of the ancient city of his ancestors, later to take a desperate plunge off the cliffs and into the harbor. The Kingsport he sees is a mirage, time-shifted back to the seventeenth century, and he apparently walks the illusion only in his mind. We have the option, as so often in Lovecraft’s stories, to believe the doctors who tell our narrator that he suffered a psychotic break. Just a momentary madness, no worries.

On the other hand, doctors who’d prescribe the Necronomicon as a way out of madness? Can’t trust them! And just because a journey took place only in the narrator’s mind, or via some form of astral projection, doesn’t mean it wasn’t a journey into the truth.

And what a truth here.

Something I’ve missed before—this narrator isn’t our usual WASP academic, professional, or student. His ancestors, at least, were a “dark, furtive folk from opiate southern gardens of orchids,” who had to learn the tongue (English) of the “blue-eyed fishers.” Hmm. I’m not sure these “dark, furtive folk” came from any particular place in the waking world. They sound more like denizens of Lovecraft’s Dreamlands, which would be cool. But maybe some obscure Pacific island? Anyhow. Our narrator is a stranger to New England, and poor and lonely, but he does read Latin, hence well-educated. He’s also familiar with the names of esoteric tomes, which displays a prior interest in the occult. On the other hand, he doesn’t instantly associate that amorphous flute-player in the catacombs with Azathoth and the other Outer Gods, like any really deep scholar of arcane lore would do. But give him a break: This story was written in 1923, only three years after Lovecraft connected monotonously whining flutes with Nyarlathotep in the story of the same name. So word might not have gotten around yet.

I find the passage in which the narrator waits in the parlor of his ancestors’ house to be one of Lovecraft’s creepiest. The “dumb” man in the wax mask! The close-bonneted old woman who never stops spinning! Whoever or whatever is sitting on the settle facing the windows, unseen and unheard by the narrator, but not unfelt. And then something maybe whirs out the windows, and after that, the narrator feels the settle’s unoccupied. This is implied eeriness on an M. R. James level!

This time, well-acquainted with the secret of the worshippers, I admired the verbs Lovecraft uses to describe their movements and hint at their true natures: slithered, oozed, squirmed, wriggled. There are also the elbows that are preternaturally soft, the stomachs that are abnormally pulpy, the catacombs described as burrows maggoty with subterraneous evil. Slightly more oblique are references to decay, clamminess, corruption, fungus, lichens and disease. Call him mad all you want, once again Alhazred is right. Guys! These wizardly ancestors of the narrator, “devil-bought” as they were in life, have survived the grave by “instructing the very worm that gnaws”—that is, by transferring mind and will into maggots and swelling them to man-size! Now that’s awesomely gross. Plus Alhazred gets to close the story with another of his lusciously quotable lines: “Things have learned to walk that ought to crawl.”

Maggot revenants are just the start. There’s also the amorphous flutist which rolls out of sight. Rolls! And where there’s an amorphous and monotonously tooting flutist, there must be some avatar of the Outer Gods. Here I’d say it’s that pillar of cold green flame. Nyarlathotep, maybe? He could do the chilly fire thing, and he always looks great in green.

Last, the Lovecraft bestiary gets a worthy addition in the highly squicky, highly hybridized mounts that answer the flutist’s call. Here’s another big challenge for the illustrator: A thing that’s part crow, part mole, part buzzard, part ant, part bat and part rotted human. Brings to mind other less than savory transport animals, like the K’n-yan “mules” of “The Mound” and the Shantak-birds and night gaunts of “Unknown Kadath.” Um, thanks, but I think I’ll just call a cab.

Next week, step into the world of dreams for “The Doom That Came to Sarnath.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.

Tis’ the season in Kingsport but the revels aren’t for everyone… An early foray into the realms of the Mythos: Kingsport is a great setting with, I think, a touch of Hawthorne. If I recall correctly, the middle two books listed are historical texts about witchcraft while Marvells is an Ambrose Bierce reference. It makes my Beyond the Horizon and Curious Warnings pale in comparison…

Weird Tales round-up:

The first appearance came in January 1925, alongside Frank Belknap Long’s “The Ocean Leech”. It made a second appearance as the classic reprint in October 1933, an issue which included Robert E. Howard’s Conan story “The Pool of the Black One”, Frank Belknap Long’s “The Black, Dead Thing”, Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Seed from the Sepulcher”, the first part of Edmond Hamilton’s “The Vampire Master” and Jack Williamson’s silly-but-fun “The Plutonian Terror”.

This story also starts with a great quotable line: “I was far from home, and the spell of the eastern sea was upon me.” I think Kingsport DOES have an identity of its own: while Innsmouth is a fishing village, Kingsport is a port city, and thus acts as a threshold. It’s strongly tied to the Dreamlands, and many of its wonders and terrors are solitary travelers who have settled here but have connections to “elsewhere”, either terrestrial lands across the sea or other realms entirely.

A great set-up, despite the adjectivitis, but ultimately it fizzles. The reveal is a little too removed from the horror for it to truly have any impact. Actually, for me it all starts to fall apart about the time they get underground. It all steps away from reality too fast to draw the reader’s belief into the story. Humanoid charnel worms ought to work, but an actual physical description would work better I think.

Schuyler is correct @1. The Glanvill and Remigius are actual books (and seriously, how did Lovecraft dig these things up), while Morryston is an invention by Ambrose Bierce and the Necronomicon we all know about. It should be noted, though, that Olaus Wormius (or Ole Worm) was a real person. He was a Danish physician and antiquary, best known for, among other things, his work on runes and figuring out that unicorn horns most likely came from narwhals. Intrasutural bones in the skull are also named for him. I don’t see how runes give him a connection to the Necronomicon, but HPL probably picked him for the name.

I got a definite Nightgaunt feel from the “steeds”. They seem to run stronger through the canon than I had thought.

ETA: I, too, had forgotten the narrator’s non-WASPishness. I think something Pacific islander is probably implied. That gives him a slight connection to Innsmouth as well.

@2: Kingsport was inspired by Marblehead, MA, where Lovecraft felt a great emotional flash of connection to the past. Has anyone here visited and, if so, did you feel a similar reaction?

Possibly of interest: http://www.salemwitchmuseum.com/tour/mbhd.shtml

@3: I think Poe cited Glanvill.

At one point the narrator mentions “the secret, immemorial sea out of which the people had come in the elder time”, which to me recalls the link mentioned in Innsmouth between Oceania and the Deep Ones. I have never seen any reason not to take this line literally.

The ironic echo/inversion of the Puritan outlawing of keeping any kind of festival at Christmas is frankly hilarious.

I also love the star motif, the way the winter stars keep almost, I guess the word is lurking overhead. Aldebaran, Orion, Sirius, Aldebaran again, the repeated implication that the deeps of space are right there watching and closer than you think.

Has anyone else also just kind of assumed that the mounts the narrator can’t describe are shoggoths? They have more attributes of bubbles elsewhere, but that’s when they’re in the act of changing shape, which he never sees any of them do, and which is the thing about them that tends to really upset people, as opposed to only unnerving them.

In conclusion, this is one of my favorite Lovecrafts, because it is one of the clearest statements of the theme that is I think the only reason that this madly racist, xenophobic, terrified-of-everybody writer remains readable, a theme that comes up somewhat in Innsmouth, but most clearly of all in The Outsider: we have met the enemy, and he is us. Lovecraft is aware that he contains what he fears. This really is the narrator’s ancestry. These are his ancestors; this is his heritage; none of that is ever denied. There’s no hint that this isn’t how the rites are supposed to go. There’s no hint that the spirits in the bodies of those transformed worms and graveyard mites are not, in fact, the ancestors in question doing exactly as they always have. And what’s the rite, really? They read from a book; they throw vegetation into the water, in an echo of many cultures’ offerings for the return of spring; we get no hint whatever of human sacrifice or darker arts, and there is no reason for the narrator to suppose that he is in danger from them, they offer him nothing but hospitality and recognition. He runs because of his prejudices and because he thinks these things are gross.

Which I think Lovecraft did know; this is the story of his where the sympathy balances most uneasily between the narrator and the supernatural. There are plenty of Lovecraft stories in which they would obviously be trying to kill the narrator, or otherwise be putting him in danger, but in this one, seeing the narrator’s escape as a failure of nerve on his part is a completely valid reading. I mean, look at the way Lovecraft is about ancient architecture, generally– he loves it so dearly, and the illusory Kingsport in the moonlight is creepily beautiful. (How great a detail is it that some of the houses are overlapping?) The narrator of this story essentially fails to face what is part of himself, which I find rather tragic.

And that’s why I can read and reread Lovecraft: he starts from this position of terrible fear and hatred of anything that he can other, but he also subconsciously recognizes from the beginning that the other is illusory, and on the very few occasions where his narrator can overcome revulsion, disgust and fear to comprehend the other, it turns out not to be so bad. Most of the time the narrators wind up in the hospital, babbling, but the potential for more remains present. We always want Lovecraft’s narrators, and Lovecraft, to be their best selves, and that desire is a tension that, for me at least, fuels returning to the texts. We want the narrator to live forever in Y’ha-nthlei under the sea; I want this narrator to have gotten on the damn shoggoth. He doesn’t, and the ambiguity as to whether that was the right decision is why I find this story haunting.

I like the interpretation that his ancestors’ spirits really are in the maggots. Slimy invertebrates are one of my own phobias, which made it easy for me to get stuck on the squicky “worms have replaced your family” interpretation. But as Rush-That-Speaks says, the former makes a stronger story.

Shadow Over Innsmouth suggests that everyone comes from the water originally, which is why it “only needs a little change to go back.” Not sure if the narrator’s ancestors are calling on the same trope, or meant to be more closely related to the Deep Ones. They get their immortality by a different route, anyway–and a more ethical one than most in Lovecraft.

JoeNotCharles @@@@@ 2: I like your interpretation of Kingsport.

Are the flying riding animals what the maggots turn into when they grow up?

How did anyone translate a book that drives the reader mad? Is a bad translation more or less dangerous than the original?

@@.-@: Marblehead is nothing like it was 1922. The interwar period saw a great deal of stagnation in New England. Once one of the nation’s economic centers, its financial and industrial power were draining away. Boston became a backwater, a condition that continued until the urban renewal efforts of the 50s.

This stagnation is one of the major influences on Lovecraft’s work. He didn’t mind the decaying atmosphere, he relished it. His description of the North End in “Pickman’s Model” was taken from life, and he was crushed when much of that ancient housing stock was torn down for tenements in the years after he wrote the story. “The Festival” was the same thing.

During and after WW2, the area changed completely. The dying fishing cities of Essex County remade themselves as tourist traps. So no, you’re to going to get any Festivalish feelings by going to Marblehead, MA these days.

Billionyear @@@@@ 8: You can get the Festive feeling, however, if you psychically time-travel, as the narrator seems to do — the Kingsport he saw was NOT the Kingsport that existed in the early 1900s.

Off to Google some psychic time-travel agencies. I hear that YithTrips is very good.

Things have learnt to walk

Things that really ought to crawl–

They’re my coworkers

Seriously, though, I’m kind of going along with Rush-That-Speaks. I always wondered if our narrator would have had a fun time if he’d jumped on one of those flying things. Even though I myself don’t like it one bit when someone jostles me, soft or hard. I thought the long-lost relatives were just zombies or necromancers or something. And how can vegetation be viscous?

Someone in a fanzine many years back interpreted the green light (I would not call it a flame if it was not hot) as symbolic of the green growth that one hopes will return when one celebrates the winter solstice. Which has in fact been going on longer than people have been around, though no entity may have been smart enough to celebrate it. Further information on how to make a flame burn green can be found on the interwebs; I myself recall a mixture of boric acid and wood alcohol, but don’t remember enough about how it was done to recommend it without further study… But this was quite an interesting review, as usual.

Perhaps I was overthinking this story. But I found myself having difficulties reconciling the different bits of background we are given about the narrator. Ethnic origins from tropical south, family coat of arms, multiple kinsmen hanged during the witch trials, deep knowledge of European occult tradition… some pieces seem to fit together, but no picture emerges. An old Spanish family somehow settled in the Colonies? An epically doomed marital union between an old-time WASP family (who just happen to be witches) and some more interestingly ethnic group (who just happen to worship Things Man Was Not Meant To Know)?

In a dream, places and categories can blur. Despite the horror aspects and all the evil books on display (including an unusually specific quotation from the Necromicon!), this story felt more Dream than Mythos to me. Perhaps we’re in some sort of alternate history where the narrator’s background actually makes sense.

Or, perhaps, the narrator is unreliable from the very beginning, i.e. some parts of his memories are false. If he is, in fact, an outsider being offerred a starring role in The Festival – well, that’s a very different reading than Rush-That-Speaks arrived at…

I still think the narrator might be from the Dreamlands, ’cause that place was lousy with orchids and such like.

The more alternative interpretations of this story we come up with, the more I like it. I’ve gone from “this story doesn’t really hold together” to “there are five interesting ways to tie this together, and they’re all shiny. And I kind of like the idea of Dreamlands immigrants settling in Kingsport a few generations before the Polish ones.

Of course, being a proper New Yorker, I have to ask what their restaurants are like. (And conveniently, we get a few ideas in next week’s story.)

@13 Ruthanna

I’m gonna guess that Dreamlands restaurants are heavy on the spices and aromas. There’s a pretty strong Orientalist thread that runs through both Lovecraft’s and Dunsany’s interpretations.

I had always assumed the flying things were byakee.

The origins of the narrator’s family seem like an idea that HPL forgot about, although a Spanish colonial aristocracy (or possibly Portuguese from Brazil) is possible.

Tobias Cooper @@@@@ 15 – Yes, Byakhee birds! Another Dreamlands connection! As I recall from next week’s story, camel heels feature in Dreamlands cuisine, along with pearl-infused vinegar.

A Byakhee bird steak might be tasty, too, well-brined, of course.

@16

I’m pretty sure eating a byakhee steak would turn your stomach in non-Euclidean ways.

Byakhee is most safely sampled (if not enjoyed) at standardized franchises like McCult’s:

“Uh, that’s a ByakheeBurger with a Formless Shake of Tsathoggua to go?”

Tobias Cooper @@@@@ 15: I would say the implied timeline doesn’t add up for Spanish colonists, but then I recall that HP’s been known to call 200-year-old houses “ancient.”

And in this story the houses in the ghost town have “antediluvian gables”.

Yep, they had tons of gables back in the pre-Flood days. In fact, the real reason for the Flood was to clear out excess gable-age. Fact.

Anybody else see the bullshit HPL article in NY Review of Books? http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2014/dec/18/hideous-unknown-hp-lovecraft/?insrc=hpma

Billionyear @@@@@ 22: You know, I tend to be more sympathetic to people being deeply critical of Lovecraft when they don’t start by mocking his readers. And wanking on about a whole genre being adolescent is… hm. I didn’t much appreciate that when I was an adolescent genre fan, and I can’t say I care for it now, either.

The entire tone of the article was “It irks me that I have to waste time even thinking about this guy.” Did the NYRB editorial board come under the idea that Lovecraft was getting too respectable and had to be taken down a peg?

And yeah, tons of good old fashioned lit society contempt for genre.

What a horrible article. If I’d been reading it on paper, I’d have hurled it across the room after the first paragraph. The utter strawman nature of the horror fans he describes in the first few paragraphs is astonishing. Incapable of experiencing the sublime, almost literally calling them “unwashed masses”. This passes for literary criticism? Then he throws them a bone by pointing out that Mary Shelley was a teenager.

I couldn’t even read the rest. He lost me utterly. I did skim and could see him grinding his teeth as he acknowledged that Joyce Carol Oates and some French poet liked Lovecraft. Why would an editor choose a reviewer with such deep disdain for his subject? I hope they get extremely erudite and well-written letters on this.

@22: I’m not entirely sure what to say but might I recommend donotlink.com? It’s a good way of making sure that attempts to mock ludicrous hatchet jobs don’t inadvertently increase the search engine ranking of said ludicrous hatchet jobs.

I’m a bit late to the party this week!

With the evocative imagery and short, compact story, The Festival has been a favorite for comic book artists for years.

Grant Margetts: Bedlam #5, 2004

Bruce McCorkindale: Fantasy Empire Presents H.P. Lovecraft, 1984

Roy Thomas, R.J.M. Lofficier, Brian Bendis, David Mack, and Marcus Rollie: H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu: The Festival, no. 1, 1993.

Esteban Maroto and Roy Thomas: H.P. Lovecraft’s The Return of Cthulhu, July 2000.

Simon Spurrier and Matt Timson: Lovecraft Anthology II, 2012.

Of course some of these have been reprinted multiple times. My absolute favorite is the most recent, by Spurrier and Timson.

There are some decent dramatic readings:

QT Audiobooks – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VHJDhwY9BDs

HP Lovecraft Audiobooks – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMxVpvoB7yc

Glenn Winkelmann – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C46x9RjCR_s

Rgunatan did the first few minutes to test his motion animation and it is beautiful. I don’t know if it was ever finished, but I hope it was. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7D2YQSaFJhI

From Spoken World Audio with added illustrations: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OjcM_sIDfUs. If you like it you can easily find the second part. This is a great way to enjoy the story!

Also try the HP Lolvecraft Literary Podcast: http://hppodcraft.com/2010/03/11/episde-34-the-festival/

I don’t know if there are any short films but it would not surprise me.

South American? Not likely. HPL doesn’t say that the narrator’s ancestors were in place when the settlers arrived, merely that his people was old even at that time. An Old World origin is far more likely.

I’m afraid I can’t go read the NYRB article as I’ve already read the NY Times Book Review Notable Books list for 2014 and have reached my implosion-to-neutron-star-of-outrage threshold over some of their choices.

So, yeah, out of respect for Earth and half the solar system, I must refrain. After all, holidays! Green pillars of fire and crow-ant-corpse steeds, tra la la! Pass me some of that protoplasmic punch, please.

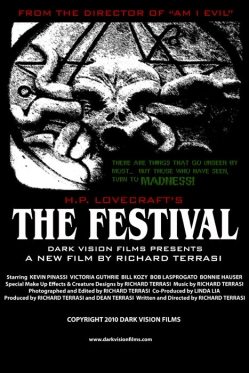

I had no idea this modern film adaptation existed–but I was not very impress’d, just now, as I watched ye trailer on YouTube.

The prose of this wee tale is close to perfection, and reflects the dream-like quality of the story. The charge of “adjectivitis” is false and is aimed at Lovecraft’s prose by readers who simply cannot comprehend Lovecraft’s multitude of fictive voices and prose styles. He was an extremely cautious artist and weighed each and every word, as can be evidenced from those places in his correspondence where he writes of his approach to fictional composition. There is not one excessive word or phrase in this beautiful story. Once again, we find Lovecraft’s conjuration of the borderland betwixt reality & dream, as he did so superbly in such tales as “The Music of Erich Zann” and “The Staement of Randolph Carter.” It is impossible to be certain if the story is memory of a dream or account of an actual experience; & this approach to weird fiction is something at which Lovecraft excelled. Leslie Klinger has some fascinating Notes for this story in his magnificent new edition, THE NEW ANNOTATED H. P. LOVECRAFT, which also reprints the Weird Tales illustration for the story, as well as phtographs of Marblehead.

Surely “The Doom That Came to Sarnath” should have been up yesterday (on Margaret Brundage’s birthday)?

We’re told it should be posting later today.

You’re slow? Despite multiple rereadings of this story over the years I only got that point about the worms after I read your commentary.

And you thought Thanksgiving with the family was bad!

World’s worst coffee table books. What a wonderful phrase!