Mad Max: Fury Road premiered to an avalanche of praise, with an astonishingly high Rotten Tomatoes score, an even higher IMDB score (it’s already at #23!), and nigh unanimous praise from everyone from The New Yorker to The Hollywood Reporter to The Mary Sue, with SBNation getting it best (I think) by saying that “Mad Max: Fury Road is a Movie Made with Caps Lock On.” Quite right. Many people also noted the film’s feminism and the environmental themes. But here was one thing I noticed: even in reviews that were a little more in-depth, many of them didn’t actually dig into what makes this film important, and how it is a giant step forward for the Mad Max series–a trilogy that seemed to go out with a hilariously over-the-top bang in 1985.

I want to take a closer look at why this film is so resonant. Spoilers abound for all the Mad Maxes (obviously) and for Thelma & Louise (come on, you’ve had, like, 50 years to watch it) and Game of Thrones (ugh). This post will discuss sexual violence, so tread carefully if you need to.

Multiple reviews referred to the film as “thin.” I would disagree–first, Miller is telling a symbolic story, not a linear one. That story happens to be about war and its aftermath, slavery, the objectification of human beings, and PTSD. The medium he uses to tell this story happens to be an action movie, more specifically a car chase. However, an interesting underlying subtext of the film is how Miller takes our expectations and subverts them. We hear “action movie” and we think San Andreas. We hear “car chase” and we think Fast and Furious. But what Miller does is practice a kind of pure action cinema. He treats a car chase movie as though it’s a 70s kung fu film, or 90s Hong Kong crime story. He’s telling a story essentially through action. When I said in my review that I thought Fury Road was one of the best films of the year, my reasoning was that it was one of the best films I’ve ever seen that took grief and trauma and, through the alchemy of George Miller’s kinetic action sequences, turned the healing process itself into an enjoyable movie.

The most effective way to talk about just how revolutionary this film is go through the various character arcs, beginning with “The Wives.”

The Wives (The Splendid Angharad, Toast the Knowing, Capable, The Dag, Cheedoh the Fragile):

A thousand years ago, in 1991, a movie called Thelma and Louise came out. It was touted as a feminist action movie, a rare notable occasion when women got to have all the fun and carnage usually reserved for male action stars. There were two BIG differences in T&L’s story, though. First, their “adventure” starts with a rape; Thelma, having escaped her borderline abusive husband for a girls’ weekend with Louise, is attacked by a random guy at a bar. Louise, luckily, finds them and points her gun at the guy.

Louise: In the future, when a woman’s crying like that, she isn’t having any fun!

Harlan: Bitch! I shoulda gone ahead and fucked her!

Louise: Why did you say?

Harlan: I said suck my cock.

She shoots him. Thus begins their road trip, as they go on the lam knowing that no court is going to buy “self-defense” when everyone in the bar saw Thelma drinking and dancing with the guy. As they plan their run across the South, Thelma tries to route them through Texas, but Louise refuses to go, and says she’ll never go back there. Thelma tries to ask why, but Louise won’t talk about it, and Thelma drops it. We never learn what happened to her, but given her intricate knowledge of rape prosecution… we can guess.

What’s the second big difference? Their adventure ends in suicide. And not a big, Armageddon-y sacrifice/suicide–they know they can’t get to Mexico, and they know they’ll never get a fair trial, so they decide it’s better to die than go to prison.

Now let’s get to Fury Road. Several reviewers chose to single out the freed women’s introduction, with one referring to the group as “a pampered harem of willowy model types…” before going on to comment on “the high level of wowza on display” and then going on to describe the scene as showing the women “in skimpy, shorty, filmy dresses, hosing one another off in lyrical semi-slow motion.” The (enthusiastic and positive) New Yorker review also dwells on this scene: “Our first glimpse of them bodes ill: limber beauties, draped in muslin underwear and hosing themselves down in the middle of nowhere. It’s like the start of a Playboy shoot…” before stating that the film “recovers” from this scene by focusing on the Vuvalini biker gang later on.

Now, forgive me for being po-faced, but the women being described are all rape victims. They’ve been crammed into a tiny, hot, waterless space under a tanker truck in order to escape their rapist. At least two of them are pregnant with their rapist’s babies. They’re not a “pampered harem”–they’re prisoners, who are risking their lives to escape sexual slavery and give their children a different life. And look at the scene again: Max doesn’t focus on the women; his attention is on the water. Water is even more precious than gasoline in this version of Mad Max (a fact underscored later on when Max washes his bloodied face with breastmilk) and they have a whole hose of it. To go even further, Miller is showing us a scene that could be sexy in the way these review describe–models in see-through clothes spraying water on each other, with the water a stand-in for a different liquid substance. But Miller subverts every aspect of that cliché. In this case the hose full of water is just a hose full of water–the most precious thing they could have in the Waste. The diaphanous dresses are their prison uniforms. (Given that no one else in the film is dressed like this, I think it’s safe to assume that these are the clothes required by Immortan Joe.) And what is the first thing they do after Furiosa lets them out? The most important thing? Even as they’re drinking water they take turns freeing each other from hideous chastity belts, reclaiming their bodies. They are no longer things, they are not a fucking harem, and they are not Joe’s slaves. The Splendid Angharad drives this home by using her pregnant belly as a shield later on, using Joe’s own child against him as he tries to shoot Max and Furiosa. Capable (played by Riley Keough) chooses to reach out to damaged War Boy Nux, comforting him with her formerly untouchable body.

Furiosa

Game of Thrones enraged a lot of people last Sunday when Sansa was raped by her new husband, Ramsay Bolton. Having avoided a nightmarish marriage to Joffrey, having received respect from her husband Tyrion, and having learned to maneuver around people more powerful than her, she has now become another one of the show’s many, many rape victims. This is used as an end of episode plot twist, a moment for the show to go off-book again, and to throw new abuse at one of the most abused characters. This will now almost certainly be her defining moment of the season–this, not the moment she declared herself Sansa Stark of Winterfell. Now here’s the utterly worst part of this Sansa plot–as several reviewers have pointed out, the camera cuts to Theon’s face. It doesn’t even stay on Sansa to record her experience, and keep this horrible scene about her and how it fits into her larger story–it makes her rape part of Theon’s story, part of his redemption.

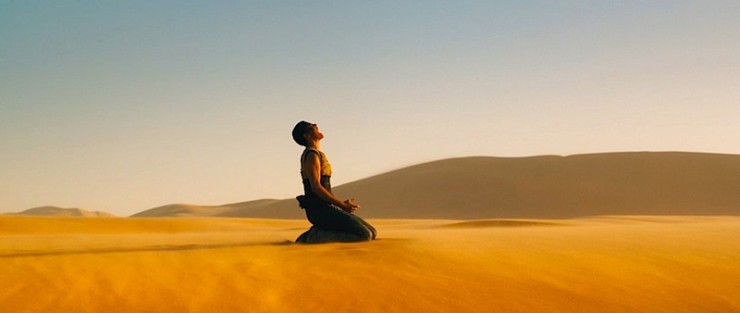

Now, let compare how George Miller treats Furiosa. After she reunites with The Many Mothers, we learn that her own mother died “on the third day”–presumably the third day after being kidnapped by Immortan Joe or his agents. It’s safe to assume that terrible things were being done to Furiosa and her mother during the trek back to the Citadel. Furiosa survived them, her mother did not. Furiosa then spent the next 20-odd years working for the man who stole her from her home, eventually becoming an Imperator. When Furiosa learns that her home is truly gone, she walks away a few feet to collapse and howl out her grief. This howl exactly mirrors Max’s collapse when he finds his murdered wife and child in the original Mad Max. Now, in a lesser film, he would comfort her, tell her the story of his loss, take her moment away from her. But no–we stay on her for this. We spend one of the few still moments in the movie watching her terrible grief from a polite distance with Max. And it’s only about a half an hour (and roughly three thousand explosions) later that Max gently takes the story back from her…but more on that in a minute.

When Furiosa finally kills the shit out of Immortan Joe, his death is framed in terms of her experience. She’s the one we watch crawling through the truck. She finally faces him, and in two words, (“Remember me?”) Charlize Theron tells us the other half of her story. We’ve already seen what she lost. Now, we get a glimpse of what her life was after she was stolen from their home.

Nux

Max is haunted by his past, and turned into nothing more than a body by Immortan Joe. But here’s the key: in the opening scenes we root for him against the powdered boys who are attacking him. As the chase begins we are rooting for him and Furiosa, and cheer as War Boys bite it. I went in blind, so I assumed Nux was dead after the crash, and thought that Miller was going for the sick joke of Max being tied to a corpse for half the movie. But no–Nux wakes up. So then I thought he was going to be the secondary antagonist, clinging to the truck and striking at Furiosa and the women from within. But no–after he fails to assassinate Furiosa and humiliates himself in front of Joe, he’s just a kid. A traumatized, enslaved kid who’s been duped into craving Joe’s approval over all else. He loses his reason for living when he fails, and has to remake himself on the run, just as the women are. Just as Max is. As the chase continues, more and more of his paints fades away, until we see the real face underneath. And this comes to mean even more as the cars continue to explode: under the paint and the war cries, every boy on those trucks is a kid just like Nux. All the drummers. Coma-Doof. Even the horrible Rictus Erectus manages to sound sweet and vulnerable as he shares the news of his brother. Miller has subverted the story again: other than Joe (and possibly The Bullet Farmer and The People Eater…), there aren’t really any villains here.

And then he takes that a step further as well. Nux has been trained to live for a fiery death, and he gets it–but he gets it on his own new terms. Having experienced something like real love with Capable, he sacrifices himself to kill Rictus and save the woman he was maybe starting to hope he had a future with. This is terrible, and I felt it more than any of the other deaths in the film, but it also allows him to transform his destiny. Rather than being a slave to Joe’s war machine, he is a free and independent young man who sacrifices himself for others by his own choice.

Max

Some have complained that Max is along for the ride, but this is in keeping with the trilogy. In the first film he isn’t even introduced for about ten minutes, and we get plenty of long Max-less scenes with his wife and Toecutter’s gang. The Road Warrior is narrated by Feral Kid, and again we get lots of scenes of Humungus’ gang, Papagallo’s people, and the Gyrocopter captain. In the end, Max is revealed to be a decoy–a fact that seemingly everyone knew but him. Pappagallo cooked up a plan to get his people to safety, and used Max, knowing he’d be in mortal danger, and that, if Max lived (a big fucking if) he’d be abandoned in the Waste with no ride. He didn’t ask Max to sacrifice himself, he played on Max’s pride in order to use him. In Thunderdome, we again get plenty of Max-free scenes, and in the end we learn that our hero has been used again, this time by two different leaders who are working to different ends. At least Max is able to choose to sacrifice himself to allow the kids to escape, but that’s only after he’s been pushed into an impossible situation. Again, he’s left at the end of the film, in the Waste, with no ride, and Savannah Nix gets the ending narration to wrap the story up for us.

Now, in Fury Road, Max gets to narrate his own story for the first time, and he chooses to help the women in the end. His name is taken away again, but this time he doesn’t even rate “Raggedy Man” or “The Man with No Name”–he is reduced to his function, and called “Blood Bag.” He refuses to give Furiosa his name when she asks for it. So she calls him “Fool.” After they make it to the Vuvalini, Furiosa gives him a bike and precious supplies that she could have kept for herself, and tells him he’s welcome to come with them across the salt flats. This is the first time in the series that he’s given a reasonable choice. After some thought, he decides to suggest going back and storming the Citadel–which in itself is interesting–and he and Furiosa shake hands on the deal, marking the first time Max is able to be truly, fairly partnered with someone, a fellow hero. And then Miller subverts heroism.

Furiosa is terribly wounded during the storm on the Citadel, and is clearly dying. Given all the other deaths in the film I figured this was it for her, and she’d be the grand sacrificial figure. Instead, Max tells her his name–which I think marks the first time in the series that he’s chosen to tell someone his name?–and then, like Nux, takes the role Immortan Joe forced on him and transforms it into something better. Having been turned into a Blood Bag against his will, he chooses to give his blood to Furiosa, and the thing that seemed like just a sick joke/dystopian objectification at the beginning of the film is turned into an act of healing. He is doing it purely to save her, but in doing it makes a new connection to humanity, and to the better part of himself, just as Nux did in his sacrifice. He becomes a hero through this healing act, not through fighting.

The Many Mothers, The Milk Mothers, and the State of Fertility

Finally, the last subversion comes in the definition of fertility. Immortan Joe believes that by forcing healthy young women to bear his children, he’ll re-populate the world with perfect children. He has women hooked up to machines to steal their milk, presumably for his own use, and that of his future children. (I hate to even ask this question, but where are their children?) The only one of Joe’s children that we see dies with his mother, The Splendid Angharad, who died in a terrible inversion of the murder of Max’s wife and child. The Mary Sue pointed out how horrific this scene is, as one of Joe’s men performs a postmortem C-section on Splendid, but as Emmet Asher-Perrin said as we left the theater, “That bastard never got to touch the baby.” Which is true, and I think the best way to read the scene: as Splendid had hoped, Immortan Joe doesn’t get to have any interaction with her child, and as terrible as their deaths are, she succeeded in protecting Max and Furiosa, freeing her fellow slaves, and keeping her child out of the hands of the monster who would have turned him into a warlord.

Joe’s fantasy of a new and fertile world is ultimately remade by the Vuvalini–the women he raided for slaves during Furiosa’s childhood. As a Forbes article points out, the Vuvalini end up paying the most in the siege of the Citadel:

Indeed, it’s the Many Mothers who end up paying the ultimate price. Max and Furiosa drive out to where the old ladies have built a decent, if hard, life for themselves. They gather them up and take them back to the Citadel, and almost all of them are killed in the process.

In Road Warrior, many of the Outpost’s survivors also die. Their leader. Warrior Woman. Almost every single one. But it was their escape, and Max was simply aiding them in it. Here we have a secondary, grey-haired group take all the bullets so that the young, pretty women can survive.

Which is a good point—I also wished more of them made it. But I would disagree that this is what the Vuvalini died for. They had been traveling through the Waste looking for fertile ground to replant, and now they knew that the seeds they’d been carrying in impossible hope would be planted and given a chance to live. By giving them to The Dag, the Keeper of the Seeds managed to ensure her plants would live after her own death.

When they return to the Citadel, the Milk Mothers have freed themselves from the machines to cheer Furiosa, and within a few moments, Furiosa sends water down to the people below. The fertility Joe hoped for has been transubstantiated into something better—seeds, freely given by their keeper, which will yield a new world.

And finally…

Much as silent film used to be able to reach across cultures and languages, Miller’s focus on action and emotion over dialogue and exposition allows us to experience the story in a direct, intimate way. The people who referred to this film as a “Trojan Horse” were completely correct—but Miller wasn’t smuggling feminist propaganda, he was disguising a story of healing as a fun summer blockbuster. By choosing to tell a story about how a bunch of traumatized, brainwashed, enslaved, objectified humans reclaim their lives as a balls-out feminist car chase epic with occasional moments of twisted humor, George Miller has subverted every single genre, and given us a story that will only gain resonance with time.

Leah Schnelbach hopes to one day rock as hard as Coma Doof Warrior. Come talk to her on Twitter!