“The Galileo Seven”

Written by Oliver Crawford and S. Bar-David

Directed by Robert Gist

Season 1, Episode 13

Production episode 6149-14

Original air date: January 5, 1967

Stardate: 2821.5

Captain’s log. While en route to deliver emergency medical supplies to Makus III, where they’ll meet another ship to take those supplies to the plague-ridden New Paris colony, the Enterprise‘s course takes them near Murasaki 312, a quasar-like formation. Kirk has standing orders to investigate any such phenomena, so he sends Spock in the shuttlecraft Galileo along with six others—McCoy, Scotty, Lieutenants Boma, Gaetano, and Latimer, and Yeoman Mears—to do scientific research on Murasaki.

High Commissioner Ferris—on board to supervise the delivery of the medicine—is opposed to this diversion, but Kirk points out that they’re two days ahead of schedule for their rendezvous at Makus, so there’s plenty of time. (Insert dramatic irony music here…)

The Galileo launches, but radiation from Murasaki affects readings and disrupts the instruments. They lose control and are pulled off course. Their message to the Enterprise is garbled, and sensors don’t work at all within the quasar. There are four star systems within Murasaki, and no way to know which one—if any—the shuttle’s headed for.

Uhura reports that there’s a Class-M planet in Murasaki, the second planet in the Taurus system. Kirk orders course set for that system.

The Galileo has, indeed, crashed on Taurus II. Boma theorizes that the magnetic field of Murasaki pulled them in. McCoy tends to folks’ injuries, while Scotty does damage control. Spock sends Gaetano and Latimer to survey the area. Spock speaks honestly to McCoy: the Enterprise will have a bitch of a time finding them since their instruments won’t work in the quasar, and it’s a really big planet, assuming they even know where to look.

Kirk is told that transporters aren’t functioning at 100% and they can’t risk beaming people, so Kirk sends the shuttlecraft Columbus out to do a visual search. Ferris is obnoxious and smug—but also right—when he says “I told you so” to Kirk, and makes it clear that he won’t let Kirk continue the search a second past the point where they might miss their rendezvous.

Scotty reports that they don’t have enough fuel to achieve escape velocity, and even if they did, they couldn’t achieve orbit without losing 500 pounds. Boma wants to know who’ll decide which three people are left behind, and Spock says he will as CO, somehow without adding the word “duh.”

During their survey, Gaetano and Latimer are ambushed by a native, who throws a big-ass spear right into Latimer’s back. Spock examines the spear, causing Boma to bitch him out for being more concerned with the type of weapon used than who it was used on. Gaetano also requests that they don’t leave Latimer’s body out there.

Latimer’s death has solved one problem: now they only need to lose 325 pounds of weight, and Mears and McCoy manage to find enough excess equipment to bring that number down to 175—but that still means someone has to stay behind. Spock also declines to lead the service for Latimer, leaving it to McCoy.

Scotty’s attempt to bypass the busted fuel line fails, and they lose all fuel—which, Spock dryly points out, solves the problem of who to leave behind. Then more natives can be heard gathering nearby. Boma recommends that they hit them hard, give them a bloody nose so they’ll think twice about attacking. Spock agrees with the logic, but is appalled by the notion of attacking them. Instead, he believes they should fire to frighten, not kill—these people will never have seen anything like phasers before, and they should scare them off.

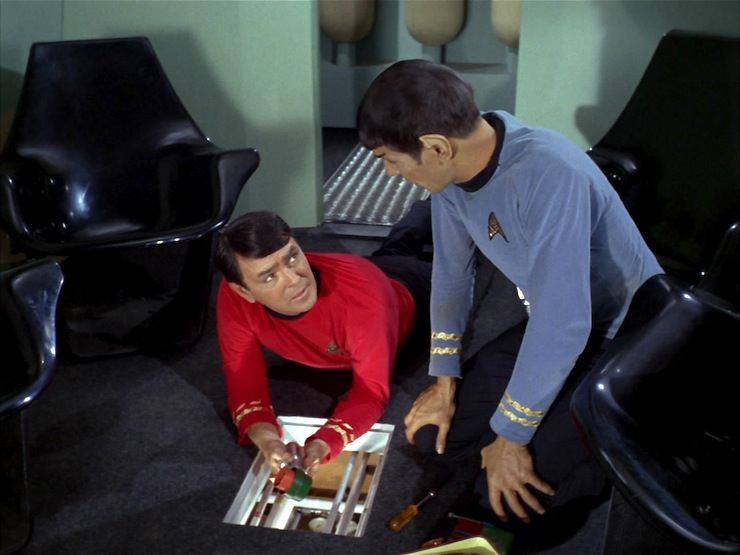

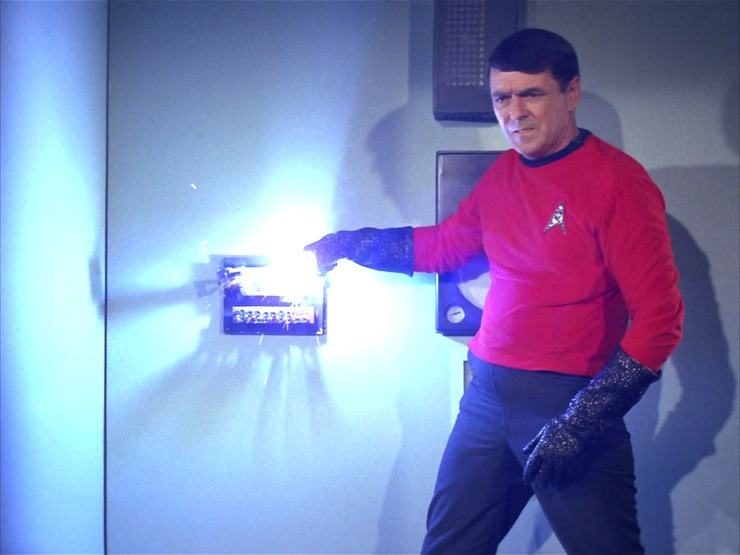

Leaving McCoy and Mears to assist Scotty, Spock, Boma, and Gaetano go off to frighten the natives. Upon their return—Spock confident that they’re scared off—Scotty suggests an alternate fuel source: the phasers. He can dump the power from the weapons into the shuttle. Spock agrees, and collects everyone’s phasers, pointing out their time crunch: in 24 hours, the Enterprise will depart for their rendezvous, and they’ll be screwed.

The engineering crew gets the transporters to function in the magnetic soup, and so Kirk adds landing parties beaming to various locations to aid the Columbus in its search. Meanwhile, Gaetano is killed by a native. When searching for him, Spock, Boma, and McCoy come across his phaser, which Spock immediately gives to McCoy to bring back to Scotty—along with Spock’s own in case he doesn’t come back. Boma and McCoy continue to be appalled by Spock’s lack of emotionalism (because, I guess, they haven’t met him?), and go give their phasers to Scotty.

Spock finds Gaetano’s body and carries it back to the shuttle, being menaced by the natives along the way as they toss spears at him. Spock is confused—his gambit of frightening the natives didn’t work, it just made them more aggressive. One native starts pounding the roof of the shuttle with a rock. Scotty needs another hour to finish his work. As the pounding continues, Spock tries to figure out where he went wrong, as he’s been so totally logical, yet two people are dead, the surviving landing party is pissed at him, and they’re being attacked. McCoy tartly reminds him that analysis can wait until later, and can we have some action, please? So he tells Scotty to use the batteries to electrify the hull, which sends the natives scurrying.

Boma insists on giving Gaetano a proper burial, which he says he’d insist on even if it was Spock who was dead—which even McCoy thinks is a step too far. Spock, however, agrees, assuming the natives don’t attack.

One of the Enterprise landing parties was also attacked, killing one crewmember and injuring three more. Just as sensor crews report that they can get readings, they hit the deadline. Ferris assumes command and orders Kirk to recall all landing parties and the Columbus. Kirk reluctantly does so, leaving Murasaki at space-normal speed to keep scanning as long as possible.

Scotty finishes his work, and they take off—but they need to use the boosters to do so, which means there’s no chance of a controlled landing. If the Enterprise doesn’t detect them after one orbit, they’ll burn in the atmosphere.

Spock decides to eject the fuel and ignite it, hoping that the Enterprise might detect that more readily than their tiny shuttle. Of course, Spock is fairly certain the Enterprise has already buggered off to their rendezvous, so it is probably a waste of time, but at least it’ll be over quickly at that point. In fact, they start to descend into the atmosphere rather quickly, with the instruments smoking, the characters all drenched in sweat, and Mears winning the Captain Obvious award with her statement, “It’s getting hot!”

However, Spock’s gamble works—Sulu picks up his improvised flare, and the five survivors are beamed out just before the Galileo burns up. Later, after McCoy tells Kirk what happened, the captain tries and fails to get Spock to admit that he committed a wholly human emotional act. Spock insists that he arrived at the desperate act logically, and agrees with Kirk’s assessment that he’s stubborn. This prompts hoots and gales of laughter from the rest of the crew, because that’s totally the appropriate thing to do after a mission where two people died…

Can’t we just reverse the polarity? Scotty comes up with the notion of dumping energy from the phasers into the shuttle engines to use as fuel. Because he’s just that awesome.

Fascinating. Given what McCoy describes as his first command situation (though he’s been in the chain of command of a starship for more than a decade at this point, I find it hard to credit that he’s never been in command of a mission before), Spock proceeds exclusively from logic, to inconsistent effect. He’s a poor leader of his human subordinates, and two of the crew are killed, at least one of which could have been prevented (Gaetano’s; Latimer’s likely would’ve happened no matter what, given that their tricorders were useless in Murasaki). When things get dicey, he spends a bit too much time trying to figure out where he went wrong and not enough taking action to make things right—though he eventually gets his head out of his ass and does so.

I’m a doctor not an escalator. This episode is the first real workout of the McCoy-tries-to-get-Spock-to-admit-to-feelings dynamic, as the good doctor pokes Spock with a stick any number of times.

Ahead warp one, aye. Sulu points out to Kirk that widening the Columbus search radius by 1% will leave a lot of land uncovered, which the captain knows, but he’s desperate to cover as much ground as quickly as possible. Sulu’s also the one who detects Spock’s improvised flare.

I cannot change the laws of physics! While McCoy, Boma, and Gaetano are busy snarking off Spock, Scotty is actually doing his job, focused entirely upon getting the Galileo fixed.

Hailing frequencies open. Uhura pretty much takes over Spock’s role on the bridge, serving as the conduit to Kirk for the rest of the crew, including finding the one Class-M planet in the quasar and coordinating the attempts to make sensors and transporters work right.

Go put on a red shirt. Gaetano is wearing gold, but he acts very much like a security guard—he’s certainly killed just like one. Latimer is the shuttle pilot, and he’s the first to go, as does a member of one of the search teams.

Channel open. “Mr. Spock, life and death are seldom logical.”

“But attaining a desired goal always is, Doctor.”

McCoy and Spock summing up their opposing worldviews.

Welcome aboard. In addition to recurring regulars DeForest Kelley, James Doohan, George Takei, and Nichelle Nichols, we’ve got Don Marshall (Boma), Peter Marko (Gaetano), Phyllis Douglas (Mears, the first of a lengthy series of post-Rand yeomen), and Reese Vaughn (Latimer) as the rest of the titular shuttlecraft team. Douglas will return in “The Way to Eden” as one of the “space hippies.”

John Crawford kicks off the bureaucrat-who-annoys-our-captain cliché as Ferris, Grant Woods plays Kelowitz, and Buck Maffei plays the big scary native.

David Ross returns as the transporter chief, having played a security guard in “Miri.” On those occasions when he was credited, he was either Galloway or Johnson, but here he’s just “transporter chief.” He’ll next be in “The Return of the Archons.”

Trivial matters: The story was pitched by Oliver Crawford as a science fictional version of Five Came Back, a 1939 film that co-starred a young Lucille Ball (co-owner of Desilu Studios, which produced Star Trek).

The part of Mears was originally written for Rand in the script, but was rewritten to a new character after Grace Lee Whitney was fired.

This is the first appearance of shuttlecraft on the Enterprise, the existence of which would’ve been handy in “The Enemy Within.” All the shuttlecraft miniature shots from this episode will be reused in future appearances of the shuttles, and despite its being destroyed, all future shuttlecraft will also be the Galileo (though the model in “The Way to Eden” will have a “II” added to the name). This episode is the only appearance of the Columbus, which is seen only once, using the Galileo miniature.

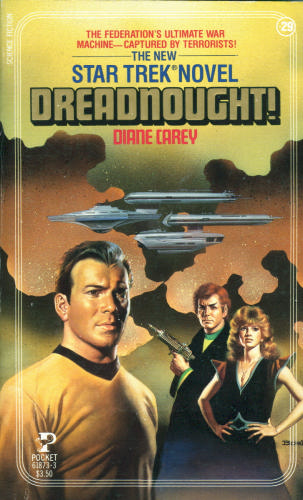

Boma appears in the novels Dreadnought! by Diane Carey (in which Scotty presses charges against him for insubordination and he’s discharged from Starfleet), the Janus Gate trilogy by L.A. Graf, and That Which Divides by Dayton Ward. Ferris is given a background in the FASA Four Years War RPG module.

Boma appears in the novels Dreadnought! by Diane Carey (in which Scotty presses charges against him for insubordination and he’s discharged from Starfleet), the Janus Gate trilogy by L.A. Graf, and That Which Divides by Dayton Ward. Ferris is given a background in the FASA Four Years War RPG module.

In addition to the usual adaptation by James Blish (in Star Trek 10), this episode was adapted into fotonovel form as part of Bantam’s series of fotonovel adaptations of episodes. In addition, the events of this episode are seen in the alternate timeline of the JJ Abrams films in issues #3-4 of IDW’s ongoing Star Trek series by Mike Johnson, Stephen Molnar, & Joe Phillips.

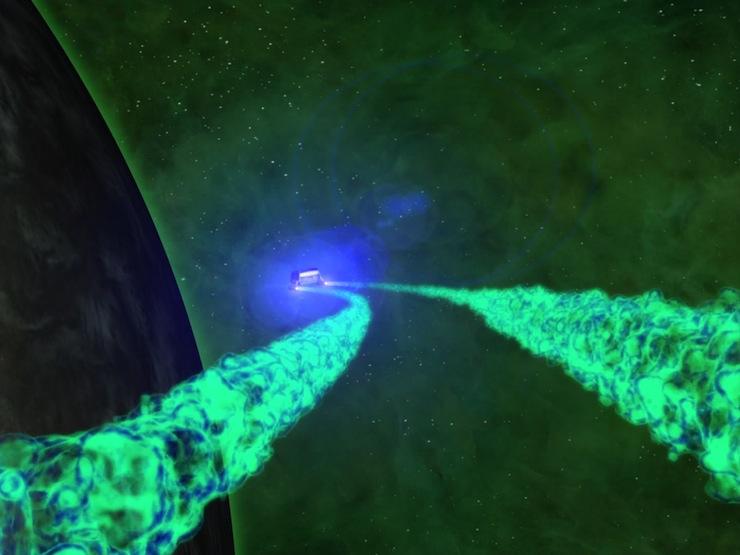

The 2007 remastering of this episode was one of the most extensive, redoing the visuals of the Murasaki quasar and of the planet of Taurus II (with the quasar’s effects more visible even in orbit), the Galileo‘s flare getting a better treatment, and actually seeing the shuttle burn up in the atmosphere as the landing party’s beamed off.

This is the first time the term “Class-M” is used to describe a planet with oxygen/nitrogen atmosphere (Earth-like, basically). The TV show Enterprise will establish that the term derives from a Vulcan designation of “Minshara class.”

To boldly go. “Mr. Spock, you’re a stubborn man.” Let us examine the myth of James T. Kirk as a maverick who always bends the rules when he isn’t breaking them, a guy who goes his own way and snubs his nose at authority.

Which is a myth, and 100% an artifact of the Trek movies. It started with him bullying his way back into command in The Motion Picture and his cheating on the Kobayashi Maru test in The Wrath of Khan, but the primary culprit is The Search for Spock, when Kirk steals the Enterprise to save Spock.

Here’s the thing: the whole point of the plot of the third film was that it was an extreme case, that saving Spock’s life was important enough to do something so unthinkable as disobey orders.

Prior to this, the only time Kirk truly disobeyed orders was in “Amok Time”—again, when Spock’s life was at stake. Basically the only reason Kirk would be anything other than a good soldier is to save the life of his best friend. (Technically, he also disobeyed orders in “The Doomsday Machine,” but he was disobeying the orders of a commodore who was obviously bugnuts and in no shape to be commanding anything, least of all Kirk’s ship.)

And yet, since 1984, the book on Jim Kirk has been that he breaks the rules, that he goes his own way, that he’s a maverick. That image has taken root in every interpretation of the character since then, whether in screen, prose, or comics form, taken to its absurd extreme in the JJ Abrams films, where Kirk’s entire history is distorted by the death of his father.

Part of that is mistaking his autonomy for being a rule-breaker, but that misses the point. In many situations in the original series (“Balance of Terror” being a good example), he’s out on the frontier on his own and has to make his own decisions. But that’s more a case of Kirk being the one to more or less make the rules because he’s totally on his own.

This episode is one of the prime examples that I like to cite when people mistakenly characterize Kirk as a maverick. Kirk not only follows regulations in this episode, he follows them doggedly and without thought to potential consequences. There’s a plague on New Paris, and the Enterprise is carrying medicine needed by hundreds of people—and he stops to examine a quasar? Really? Murasaki 312 has been there a really long time, would it not have made more sense to note its position, finish the mission of mercy, and then go back and play with the quasar? We’re talking something the size of four star systems, so realistically they’d need a helluva lot more than the two days Kirk had to examine it properly.

Kirk’s justification? He has standing orders to investigate quasars and quasar-like phenomena. Okay, then. Not exactly the actions of a go-your-own-way maverick, now is it?

What’s most notable about this episode is that the characters who we’re supposed to be rooting for—Kirk, Boma, Gaetano, McCoy—are the ones who come across the most unlikeable, while the “bad guys”—Spock for not being human enough, Ferris for being a bureaucratic snot—are actually the sympathetic ones. Spock may not be very human, but the pointed ears and the funny eyebrows and the green blood should be a clue as to why that really isn’t a consideration with him. The “why can’t you act like normal people” argument made by McCoy and Boma especially is frankly pretty ugly (and even more ironic coming in part from a character played by an African American). And for all that Ferris embodies what will become the Trek cliché of the obdurate bureaucrat, the fact of the matter is that Ferris is absolutely right. Kirk never should have stopped to stare at the quasar. Kirk’s served in space long enough to know that Murphy’s Law is the order of the day out in the black, and two days isn’t enough time to do anything useful, nor enough time to fix an unexpected problem.

I was always grateful to Diane Carey for establishing in her novel Dreadnaught! that Scotty hauled Boma up on charges, because holy cow, what a tool that guy is. His behavior toward Spock is insubordinate and insulting, and it gets to the point that even McCoy says he’s going too far. And his insistence on things like a “proper” burial (it’s only proper in some cultures) when there are ten-foot-tall anthropoids throwing spears at you is such an extreme case of sentiment over rationality that it makes Boma out to be an idiot. Admittedly, a lot of this is 1966 Hollywood attitudes, where middle-class white male Protestant values were considered the apex of humanity and anything else was deviant or weird, but it doesn’t make it any easier to stomach watching it now.

Where the episode shines is as a vehicle for Spock. As established in “The Naked Time” and “The Enemy Within,” Spock’s human and Vulcan natures are constantly at war with each other, and when he’s put in command, he wants very much for the Vulcan side to be dominant. He obviously thinks the Vulcan philosophy of logic is superior to that of the more emotional and sentimental human philosophy. To his credit, he later sees where logic falls down, particularly in ascribing motives to the natives—but we also see the good parts of it, like his unwillingness to blithely kill the natives despite Gaetano and Boma’s urging.

I do wonder what all those people were doing there. This was supposed to be a two-day scientific survey of the quasar. Latimer was there to fly the ship, and one assumes Boma was there for his scientific expertise (he’s the one with a theory about why the Galileo lost control and crashed), and Mears was there to record everything, but what were Gaetano, Scotty, and McCoy there for? I guess McCoy in case someone got hurt, but Scotty mainly seems to be there to fix the shuttle—but that’s only necessary because it crashed. And Gaetano’s job is never specified.

Oh, well. There are bits of a good episode here, but too often the script’s intended effect and actual effect are at odds with each other.

Warp factor rating: 5

Next week: “Court Martial”

Keith R.A. DeCandido‘s short story collection Without a License is now on sale from Dark Quest Books. It includes nine stories from throughout his twenty-plus years of writing, plus brand-new tales in the Dragon Precinct and Cassie Zukav milieus. You can order the trade paperback from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or directly from the author; the eBook edition will be on sale soon.