Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

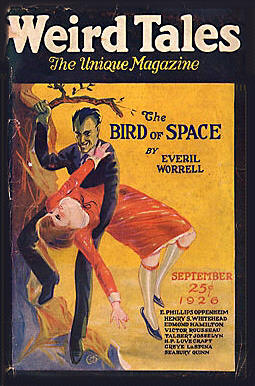

Today we’re looking at “He,” written in August 1925, and first published in the September 1926 issue of Weird Tales. You can read it here.

Spoilers ahead.

“So instead of the poems I had hoped for, there came only a shuddering blankness and ineffable loneliness; and I saw at last a fearful truth which no one had ever dared to breathe before—the unwhisperable secret of secrets—the fact that this city of stone and stridor is not a sentient perpetuation of Old New York as London is of Old London and Paris of Old Paris, but that it is in fact quite dead, its sprawling body imperfectly embalmed and infested with queer animate things which have nothing to do with it as it was in life. Upon making this discovery I ceased to sleep comfortably….”

Summary: Our narrator, an aspiring poet, wanders the night streets of New York to save his soul. His first sunset glimpse of the city thrilled him, for it appeared “majestic above its waters, its incredible peaks and pyramids rising flower-like and delicate from pools of violet mist.” But daylight reveals squalor, architectural excess, and swarms of “squat and swarthy” foreigners. The terrible truth, the unwhispered secret, is that New York is dead, a corpse infested with “queer animate things” alien to its former glories.

Now narrator ventures forth only after dark, when “the past still hovers wraith-like about.” He chiefly haunts the Greenwich section, where rumors have led him to courtyards that once formed a continuous network of alleys. Here remnants of the Georgian era persist: knockered doorways and iron-railed steps and softly glowing fanlights. Around 2AM on a cloudy August morning, a man approaches him. The elderly stranger wears a wide-brimmed hat and out-dated cloak. His voice is hollow—always a bad sign—his face disturbingly white and expressionless. Even so, he gives an impression of nobility, and narrator accepts his offer to usher him into regions of still greater antiquity.

They traverse corridors, climb brick walls, even crawl through a long and twisting stone tunnel. From the growing age of their surroundings, it’s a journey back through time as well as space. A hill improbably steep for that part of New York leads to a walled estate, evidently the stranger’s home.

Undeterred by the mustiness of unhallowed centuries, narrator follows the stranger upstairs to a well-furnished library. Shedding cloak and hat, the stranger reveals a Georgian costume, and his speech lapses into a matching archaic dialect. He tells the story of his—ancestor—a squire with singular ideas about the power of human will and the mutability of time and space. The squire discovered he’d built his manse on a site the Indians used for “sartain” rites; his walls weren’t enough to keep them out when the full moon shone. Eventually he made a deal—they could have access to the hilltop if they’d teach him their magic. Once the squire mastered it, he must have served his guests “monstrous bad rum,” because he was soon the only man alive who knew their secret.

Anyhow, this is the first time the stranger’s ever told an outsider about the rites, for narrator is obviously “hot after bygone things.” The world, he continues, is but the smoke of our intellects, and he will show the narrator a sight of other years, so long as he can hold back his fright. With icy fingers, the stranger draws the narrator to a window. A motion of his hand conjures New York when it was still wilderness, unpeopled. Next he conjures colonial New York. Then, at the narrator’s awed query of whether he dare “go far,” the stranger conjures a future city of strange flying things, impious pyramids, and “yellow, squint-eyed” people in orange and red robes, who dance insanely to drums and crotala and horns.

Too much: the narrator screams and screams. When the echoes die, he hears stealthy footsteps on the stairs, muted as if the creeping horde was barefoot or skin-shod. The latch of the locked door rattles. Terrified and enraged, the stranger damns the narrator for calling them, the dead men, the “red devils.” He clutches at the window curtains, bringing them down and letting in the moonlight. Decay spreads over library and stranger alike. He shrivels even as he tries to claw at the narrator. By the time a tomahawk rends open the door, the stranger is no more than a spitting head with eyes.

What barrels through the door is an amorphous, inky flood starred with shining eyes. It swallows the stranger’s head and retreats without touching the narrator.

The floor gives way under him. From the lower room he sees the torrent of blackness rush toward the cellar. He makes it outside, but is injured in his climb over the estate wall.

The man who finds him says he must have crawled a long way despite his broken bones, but rain soon effaces his trail of blood. He never tries to find his way back into the obscure, past-haunted labyrinth, nor can he say who or what the stranger was. Wherever the stranger was borne, the narrator has gone home to New England, to pure lanes swept at evening by fragrant sea-winds.

What’s Cyclopean: The New York of the author’s imagination, before his arrival and disillusionment, holds cyclopean towers and pinnacles rising blackly Babylonian under waning moons.

The Degenerate Dutch: This is one of Lovecraft’s New York stories, so brace yourself. Aside from the usual run of OMG IMMIGRANTS AND BROWN PEOPLE, we also get dark arts that could only be a hybrid of those practiced by “red Indians” and THE DUTCH!

Mythos Making: A glimpse of far-future New York looks suspiciously Leng-like, plus there are hints that He might be involved with the same research circles as our old friend Curwen from “Charles Dexter Ward.” Not to mention yet another winding back street impossible to find once fled—there seem to be a few of these in every major city.

Libronomicon: This story could use more books.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Does massive xenophobia count? How about irrational terror of languages you don’t speak?

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I’m writing this on Thursday June 18th, and really not inclined to be sympathetic to racism. In a hundred years, people will excuse certain moderns by saying they were just products of their time, and as ever it will be both an unwitting condemnation of the time and an excuse for precisely nothing.

I’ve already expressed my profound irritation with Lovecraft’s reaction to New York, in “Horror at Red Hook” and to a lesser extent “Cool Air.” This is more on the Red Hook end, though it has some minor redeeming features that Red Hook lacks. But first, the narrator (Howard, we could call him, choosing a name at random) whines about how the city lacks history(!), how it’s full of horrible immigrants with no dreams(!), how it’s so oppressive and terrifying that the only thing for it is to wander around in dark alleys all night and occasionally talk to the suspicious people you meet there, because Pure Art. Tourists, ugh.

If the presence of people who are a little different from you oppresses your art, you maybe need to reconsider your life choices. Just saying.

So, right, he meets this creepy guy in a dark alley who offers to show him historical sights for the truly refined—also he has candy. Eventually He leads the narrator home, where they share secrets that cannot abide the light of day—the subtle symbolism of which I should probably leave to Anne. But he does all this because the creepy old necromantic vampire seems like the friendliest, most familiar thing in this city full of weird people who speak other languages. This is also the sort of thing that should make you reconsider your life choices.

Setting aside the bigoted whining and the artistically pretentious angst, the inclusion of Native Americans in the back story brings an irony that I’m not entirely sure was unintentional. Vampire dude stole the secret of immortality from the local natives, then gave them “bad rum” (read “smallpox blankets,” and I wonder if Howard was familiar with that historical tidbit, which at one point was taught more frequently and with greater approval than it is now). And then the spirits of those natives (we’re not particularly scientific this week) rise, attracted by his timey-wimey showing off, and have their vengeance. (Sure, he blames the screaming, but what’s more likely: ancient enemies summoned by your audience yelping, or by your own unwisely ambitious magic?)

One is minded that New York was itself stolen from Native Americans (though not the ones who sold it, of course). Admitting that would, of course, involve admitting that the city does have history, and rather a lot of it. But the parallel seems unavoidable. And a great part of Lovecraft’s racist fears, shown plainly in “Shadow Out of Time” and “Doom That Came to Sarnath” and “Under the Pyramid” and… I’m not going to list them all because word count, but my point is that when you’re on the top of the heap, the idea of the people you’ve “justly” conquered getting their due is pretty terrifying. Vampire dude isn’t the only character in this story with something to worry about.

Vampire dude’s timey-wimey show is interesting, the best part of the story. New York of the prehistoric past, New York of the distant abomination-overrun future… these themes are played out far better elsewhere, but it’s odd to see them here, where the thing they place in dizzying perspective isn’t something the narrator likes. Does Howard find it comforting to think that the modern city will eventually fall to eldritch ruin, or is that Leng-like future city just what he sees as the logical end point of the world outside his Red Hook window?

Fleeing the horrors of New York, our narrator heads home for New England—where as we know, he should be just fine, provided he avoids bike tours, abandoned churches, run-down houses, municipal water supplies…

Anne’s Commentary

Lovecraft admits to the dream-origin of a number of tales; still more have the feel of dream-origin. “He” is one of them, but it appears to have been the product of a waking dream. In August, 1925, Lovecraft took a night-long walk through New York streets about which the past still hovered, wraith-like. He ended up taking a ferry to Elizabeth, New Jersey, where he bought a notebook and wrote the story down. Feverishly, I imagine, with a cup of cooling coffee on the park bench beside him.

The opening paragraphs read like overwrought autobiography, a cri de coeur of loneliness, disappointment and alienation. Our narrator’s romance with New York was brief. That first sunset glimpse recalls Randolph Carter’s ecstasies over the Dreamlands metropolis of the day, but further acquaintance reduces the city to something more like the soullessly colossal towers of the Gugs, coupled with the squalor of Leng. Even the so-called poets and artists of Greenwich Village are no kindred souls, for they’re pretenders whose very lives deny beauty. Bohemians and modernists, I guess, no better than that Sherwood Anderson who had to be given a come-uppance in “Arthur Jermyn.”

I wonder that Lovecraft should have found New York so shocking. In the early twentieth century, Providence was hardly a paradise of preservation, and Lovecraft knew it. By the time Charles Dexter Ward was able to begin his famous solitary rambles, Benefit Street was becoming a slum, its Colonial and Georgian and Victorian houses going to seed as the well-to-do retreated higher up the hill. Immigrants had begun arriving en masse by the mid-nineteenth century; Providence had a Chinatown, and Federal Hill hosted the Italian neighborhood Lovecraft would describe with distaste in “Haunter of the Dark.” And when Charles eventually ventured all the way down College Hill to South Main and South Water Streets, he found a “maelstrom of tottering houses, broken transoms, tumbling steps, twisted balustrades, swarthy faces, and nameless odors.” Sounds kind of Red Hookish to me.

Familiarity does make a difference, though, especially to us Rhode Islanders. We’re infamous for sticking to home ground. This very afternoon, I took a friend to Swan Point Cemetery, which he found a place of novel wonder, one he’d never explored despite living and working within walking distance most of his life. There’s also the truism that Rhode Islanders pack a bag to go from Pawtucket to Cranston, a distance of, oh, ten miles. Like Charles, Lovecraft must have been able to overlook Providence’s flaws, at least enough to feel a lift of the heart upon every return. Home is home, first Providence, then New England, whose beauties are consolidated in the sunset city of Randolph Carter’s longing.

New York, though! There Lovecraft’s a stranger in a strange (and much bigger) land. As a new husband, he’s also on unfamiliar interpersonal ground, nor can he take comfort in stable finances. Any dream connected with his move has turned dingy, and he’s no Randolph Carter, able to speak the languages of creatures as diverse as Zoogs and ghouls. Hence “He.” Hence “Red Hook.” Hence “Cool Air.” Noise! Crowds! Smells! Foreigners so unreasonable that they speak in foreign tongues! And they don’t have blue eyes. Though, to be fair, neither do all Anglo-Saxons. Even in New England. But at least they speak English.

Mid-story, autobiography becomes wishful musing—the narrator’s nocturnal prowls bring him to the edge of old New York, disjointed courtyards that hint at a hidden realm. Then a stranger comes along to guide him into the very heart of the ghost-city. So what if you have to traverse an obscure labyrinth of streets into growing antiquity, as in the later “Pickman’s Model“? So what if you have to surmount an improbably steep hill, also into antiquity, as in the already penned “Music of Erich Zann“? So what if your guide speaks in an archaic dialect? It’s still English. Familiar, with the deeper familiarity of racial memory. The ghost-city and manse themselves soothe with racial memory, even if the manse does smell a bit—rotten.

And anyway, familiarity isn’t all. Reality itself is empty and horrible, right? Wonder and mystery are powerful lures to the poetic mind. It’s not so bad to see the unpeopled past of New York. It’s pretty cool to see its colonial past. If only the narrator had stopped there, because the far future he asks to preview turns out to be his worst nightmare: New York taken over by “yellow, squint-eyed people” who dance to weird music. Like the beings of Ib! Like the men of Leng! Like the mindless Outer Gods themselves! Lovecraft does not approve of dancing, it seems.

Epiphany! That vision of the far future? I bet it’s the cruel empire of Tsan-Chan, and what’s so cruel about it is that the Emperor makes everyone dance to ear-aching tunes. Horribly. Ooh, and that amorphous and inky conglomeration of ghosts? With its constellations of shining eyes? Isn’t that a protoshoggoth?

Funky little story. So many tropes that other stories use more effectively, even brilliantly. The parallel world hidden close to mundane reality. The accessibility of past and future. The attractions and dangers of magic. The inadvisability of showing someone scary stuff when a scream is likely to summon hungry and/or vengeful nasties.

These poets and poet-wannabes. They may faint. They may crawl blindly off, unable to remember how they escaped the nasties. But they will always, always scream.

Next week, we explore the terrifying nexus of old houses and cosmic chasms in “Dreams in the Witch House.”

Two additional notes: First, as we run low on the really well-known Lovecraft stories, we’re going to start interspersing some Mythosian classics by other writers, starting later in July with “The Hounds of Tindalos.” Audience suggestions welcome, bearing in mind that older works, freely/legally available online and with deceased authors who can’t object to a sharp opinion or two, are preferred.

Second, while we failed in our search for a cover that included the title of this week’s work (“Lovecraft He” is a lousy search term no matter how you vary it), we learned that there’s now a Lovecraft-themed restaurant and bar on Avenue B. Mock New York if you dare; it’ll get you in the end.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land.” (And if you check back on Wednesday, “The Deepest Rift” will be up as well.) Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “Geldman’s Pharmacy” received honorable mention in The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror, Thirteenth Annual Collection. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” is published on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. She currently lives in a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island.

“He” is a great trip through time wrapped in a mediocre frame. “The Shadow Out of Time” does this kind of thing better.

Weird Tales: September 1926 wasn’t a great issue: Derleth and Schorer’s “The Marmoset” is here alongside reprints of the poems “Ozymandias” and “Eldorado”.

It’s amusing to think: that the families of foreigners Lovecraft so reviled included the likes of Isaac Asimov and Richard Feynman.

I wonder whether: that Lovecraft-themed bar serves Narragansett? ETA: Yes they do!

If you want to do any of Clark Ashton Smith’s stories: most of them can be found at this authorised website: http://www.eldritchdark.com/.

I think the beginning of this story is probably the most honest thing Lovecraft ever wrote. He has likely captured all of his feelings about his initial move to NY and what the city held. Certainly his distaste for the “foreign elements” is problematic, but the fact that the city lost some of its allure in the light of day is probably true just about anywhere. The final line also has a certain beauty to it, and may well reflect Howard’s homesickness.

The stranger’s home is clearly in that strange city space which includes the Rue d’Auseil and the part of North Boston where Pickman had his studio. The church that housed the Haunter of the Dark doesn’t seem to have been in such a space, though it may well have been adjacent; nobody, from Robert Blake to the police, seems to have had any difficulty finding it. Most cities large enough must have these odd corners holding surprises that can never be found again. It occurs to me that I encountered such a space in Paris 35 years ago. I was just roaming around and stumbled on a courtyard with a sculpture that included a rooster and a dragon mounted about 10 feet up a wall. I have no idea where I was other than not too far from the Pompidou and couldn’t have found it again the very next day.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 2: It pleases me to think that your courtyard of the rooster and dragon was the residence of Curwen’s Paris correspondent. It’s probably best you don’t remember the way back.

I found, one time, an entrance into an abandoned train tunnel in Troy, New York, under which a swift black stream ran, always audible, rarely visible through holes eroded in the tunnel underpinnings.

Probably a good thing I never could find that entrance again, only the stream debouching into drains that led down to the Hudson.

Anyway, not that you would, but don’t drink out of the Hudson at Troy!

I notice the restaurant/bar seems heavy on fish items and light on cheese, so I don’t think HPL would have found it to his taste.They don’t post the desserts, so no indication of how they stand on coffee ice cream or pie ala mode.

@3 Anne

I wish I still had my photos from that trip. As I recall, there was a sphere with a band around it, the rooster, the dragon, maybe a man. All in brass and some bit above head height. Perhaps there was some sort of clock function, or is that a trick of my memory? Thinking about it now, it has a very Chambersesque feel to it.

@5: I’ve been trying to find this for an hour. Is it this: http://www.coolstuffinparis.com/le-defenseur-du-temps.php?

ETA: A video of it in action: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=teG9q9AbX_0.

SchuylerH @@@@@ 6 I’ll bet that is indeed it! And I want one — one in working order. Or maybe NOT in working order? Wonder versus fear and all that.

Plot bunny, for sure. What if the automaton did suddenly start up again? And the defender of time lost? Or what if this thing is a Yith device? Or what about the nearly hidden crab? Mi-Go reference?

Coolness of the day, probably week, maybe month!

Most of the tales out of the Arkham House collection “Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos” are excellent for this blog. I especially love some Clark Ashton Smith (nobody drops the word Satanist better than him, in my opinion) with “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis”, “Ubbo-Sathla”, “Genius Loci” and “the Treader of the Dust” being stand outs. Then you have the authors who inspired Lovecraft: William Hope Hodgson’s “House on the Borderland”, Arthur Machen’s “the Great God Pan” and “Three Imposters”, and Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows”.

Also, there are plenty of board games based off of Lovecraft you could review including Arkham Horror and Mansions of Madness. Both are very fun albeit a little confusing when learning all the rules.

Let’s all end racism together!

@6 SchuylerH

My God, you are amazing. That’s the very thing! Apparently it was pretty new when I saw it in July of 1980. And it’s right there in the first sentence: “hidden in a sort of courtyard in a little shopping center just north of the Pompidou…” I don’t think I saw it in action. I would have remembered that.

SchuylerH @@@@@ 6: Probably there are pictures of the Rue D’Auseil posted on Instagram, too. The challenge of modern horror writers, as ever, is to adapt tropes so that they take advantage of better communication rather than suffer from the ability to send a quick text.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 2: I’m all sympathy for people getting disillusioned with the Big City. I’m less sympathetic to the Purity of Pure Art (especially when it depends on the nastier sort of Purity), and the two are far too tangled up here for my tastes. New York is plenty overwhelming, and has a big enough dark side, without trying to claim that it has no history or devolving into a puddle of goo over people speaking unfamiliar languages.

But then, part of what I love about New York is that it’s big enough, and deep enough, to be the sunset city and the Plateau of Leng, Arkham and Y’hanthlei all at once. And I love it in small doses for just that reason–keep me there too long and I start writing misanthropic dystopian cyberpunk, but I don’t forget that the rest of the crowd has stories and dreams as well.

All: Love the suggestions for additional reads and fun modern stuff–keep them coming!

Hmm, my response to Schuyler has vanished into moderation. That is indeed the thing I saw, though I remembered the courtyard as less open and the clock as smaller. After a bit of searching, I found a video of the thing in action: https://vimeo.com/114416504

As for other stories, Robert Howard is 79 years safely dead, so some of his mythos stories should be findable. Unfortunately, off the top of my head I can’t think of any of the titles. “Pigeons from Hell” is a terrific horror story, but it isn’t mythos. One of my favorite mythos stories is “Black Man with Horn” by TED Klein. That one is rather less public domain, alas, and so might not be easy for everyone to find.

ETA: Ah, I’m out of moderation. There was a problem when I tried to copy & paste the quote from Schuyler’s website find. I’ve fixed that.

A suggestion for other stories to review. How about touching upon some of HPL’s inspirations maybe Repairer of Reputations or The Yellow Sign by R W Chambers or some of Lord Dunsany’s Dreamlands stories.

Interesting thoughts.My comments:

Anne:”Epiphany! That vision of the far future? I bet it’s the cruel empire of Tsan-Chan,”

Yeah, that’s what I was thinking.After all, Tsan-Chan is located in the far future (5,000 AD).

Cycles of Conquest: In the HPL cosmos, no one stays on top (well, except for the Great Race of Yith).Amerinds get conquered by Dutch.Dutch get conquered by Anglo-Americans.Anglo-Americans get conquered by….cruel empire of Tsan-Chan?Someone quite fiendish at any rate

He meets Joseph Curwen: Surely someone has done this? The timeframe matches up so well…

The story itself: Interesting ideas, but it’s too abbreviated.This needed to be novella-length.

He’s home: according to Joshi (“A Life,” 372) Lovecraft based the location and description of He’s estate on a real place in NY.

Ruthanna: “(read “smallpox blankets,” and I wonder if Howard was familiar with that historical tidbit, which at one point was taught more frequently and with greater approval than it is now).”

Was it taught with more approval? I know that Francis Parkman ( who unearthed the Amherst letters involving the smallpox scheme) called it “detestable,” and Parkman was not exactly known for being overly compassionate where Amerinds were concerned.

I would suggest “Slime” by Joseph Payne Brennan, but I don’t recall if it’s up online.

Howard’s “Worms of the Earth”, for sure.

Some of the work of C.L. Moore [“Black Thirst”] and Leigh Brackett [“Purple Priestess of the Mad Moon”] feel definitely Mythos-ish.

“The Double Tower” and “The Stairs in the Crypt” by Lin Carter, the latter mainly for comic relief–I don’t recall if these are online either, but both are found in Chaosium’s “Book of Eibon”.

After reading each day’s news, I wonder if HPL or anyone else should be calling Tsan-chan all that cruel…

After reading this story and considering where the house was and which way the window faced, I was convinced that it had an excellent view of the World Trade Center, if you set it to the appropriate time period. Speaking of hideous visions of the future…

@11: The more I see of that clock, the more it unnerves me. I want one!

@14: http://www.www3.reocities.com/Paris/villa/4018/texts/Slime.html

Expanded Mythos stories: Lovecraft’s inspirations from “Supernatural Horror in Literature” are pretty much all public domain now, so Chambers, Hodgson, Bierce, Blackwood, Dunsany, James, Machen, Poe etc could all be mixed in.

Where Howard is concerned, I would recommend “The Black Stone” and “Worms of the Earth”.

One of my personal favourites is the great Fritz Leiber, though I think his most explicitly Lovecraftian story (“The Terror from the Depths”) is one of his lesser efforts. All of the stories in Wildside’s collection Writers of the Dark touch on Lovecraftian themes in some way, I particularly like “The Dreams of Albert Moreland” and “A Bit of the Dark World” and “To Arkham and the Stars”.

In terms of more recent stories, Brian McNaughton’s “The Doom That Came to Innsmouth” and T. E. D. Klein’s “The Events at Poroth Farm” can be had for 76c as part of an ebook, The Cthulhu Mythos Megapack. David Drake’s “Than Curse the Darkness” is online.

@Schuyler

I still want to know how the hell you managed to find that clock based on my description. Your Google-fu is impressive.

Another thought for other stories: There are a couple of Laundry stories right here on Tor! I also agree that going through the stories mentioned in “Supernatural Horror” could be interesting. It might also be worthwhile trying to look at some of the art/artists HPL mentions in some of his stories. We’ve talked briefly about some of them in the comments, but nothing in depth.

@17: It wasn’t that hard once you mentioned that it was a clock. For a contrast with the Laundryverse, “A Colder War” is also online. An art post would be a great idea and an excuse for me to post some Virgil Finlay.

RE:non-HPL Lovecraftian tales,

Robert Barbour Johnson’s “Far Below” (it takes the subway stuff in “Pickman’s Model” as it’s jumping off point)

https://books.google.com/books?id=_LTtvNnkAhsC&pg=PA11&dq=far+below+robert+barbour+johnson&hl=en&sa=X&ei=SauKVYbVJcHo-AHDjoHgDw&ved=0CB0Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=far%20below%20robert%20barbour%20johnson&f=false

Trajan23 @@@@@ 13: I’ve heard that it was described with approval in his namesake town for a while, and sometimes elsewhere, long before Amherst became part of the reassuringly hippy-ish “Happy Valley.” No good cites for that; it may be a local bias. The Valley has its own myths.

Angiportus @@@@@ 14: The assumption that there are societies that aren’t cruel, and that do consistently stand against cruelty, is what I always think of when people claim that Lovecraft is pessimistic. Admittedly he seems to have a rather unclear idea of what such societies ought to look like…

SchuylerH @@@@@ 16&18: There are reasons I’m inclined to avoid some of the modern stories that have less to do with accessibility, and more to do with this dot of Etiquette that I could swear I put on my character sheet somewhere. I’m happy to speak ill of the famous dead, especially when I can also speak about admiring the hell out of them. I’m more cautious about expressing my thoughts about stories by living writers in my chosen sub-sub-sub-genre–some of which I could easily compare unfavorably to “Red Hook.”

Syon @@@@@ 19: And I do have a weakness for subway-based fantasy.

Might pick out a few with an eye to positive recommendations, though–I do love “A Colder War.”

@20: I entirely understand your position: I will still second (third? fourth? nth?) and highly recommend T. E. D. Klein’s stories, particularly the excellent “Black Man with a Horn” which incorporates a metafictional look at the Lovecraft Circle.

“He” actually puzzles me a bit. The narrator seems an obvious stand-in for the writer, yet the story expressly undermines the narrator’s world view. It isn’t an uplifting ‘be true to yourself’ morality tale. The narrator is nearly destroyed by his obsession with the virtues of an imagined past, led on by your basic vampire (the go-to literary metaphor for ‘dead hand of the past,’ in the era before vampires became teen heartthrobs).

Perhaps HPL recognized the absurdity of many of the narrator’s prejudices, but wasn’t able to overcome them. Try to picture HPL as a tourist in, say, Egypt. He’d love it, if he weren’t so busy being utterly miserable… just like his actual interlude in a modern-day Babylon like New York City. Perhaps I took this bit of pulp fiction too seriously, but I’m left feeling that the writer had recently lost some cherished illusions about himself.

On a less depressing note, I remember liking Machen, “The White Powder,” and Hodgson, “Boats of the Glen Carrig” – not Mythos, but perhaps of interest as related works.

jgtheok @@@@@ 22: Self-destructive but irresistible searches for knowledge show up over and over in Lovecraft’s stories. I hadn’t thought of it here because on the surface (and to someone a little more used to New York), following a vampire down a back alley seems much dumber than reading the Necronomicon in the comfortable confines of a university library. But I suspect he intended them the same way–for someone whose primary social interaction was always through the internet written correspondence, the distinction between dangerous writing and dangerous people may have been pretty fuzzy.

@21 SchuylerH<

Favorite line in “Black Man With a Horn”: When the narrator says “Ah Howard, your triumph was complete when your name became an adjective.”

And that standard does put HPL in some elite company.After all, we can set Lovecraftian alongside Shakespearian, Dickensian, Byronic, Chaucerian, etc

RE: the poisoned rum,

I wonder if HPL was thinking of this incident and not Amherst:

“In 1623, Dr. Potts gained notoriety as the individual who prepared the poison served the Native Americans during a “peace ceremony” at Jamestown, killing 200 of them in retaliation for the Indian Massacre of 1622 which killed nearly a third of the colonists the preceding year.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Pott

“Colonists who survived the attacks raided the tribes and particularly their corn crops in the summer and fall of 1622 so successfully that Chief Opechancanough decided to negotiate. Through friendly native intermediaries, a peace parley was arranged between the two groups. Some of the Jamestown leaders, led by Captain William Tucker and Dr.John Potts, poisoned the Powhatans’ share of the liquor for the parley’s ceremonial toast.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_massacre_of_1622#Indian_poisoning

The parallel seems closer with Potts

After you run out of famous HPL stories (oh, BTW, will you include Hypnos? Such an interesting little thing) I wouldn’t mind to see reviews on some of the most famous collaborations as well, like Medusa’s Coil and Out Of Aeons. In the Walls of Eryx also seems very relevant to your interests.

As for non-HPL works, Machen would be very appropriate, I think. Especially The Great God Pan and White People.

Ruina @@@@@ 26: I can offer immediate gratification for at least part of your request. We’ve been including the collaborations in our drunkard’s walk of Lovecraft’s original stories; Out of the Aeons is here. If you check the archives (though not, alas, the Archives, at least not on this site), you’ll find plenty of obscure stuff as well as the more famous stories.

The Reread, like the universe itself, lacks any order other than that which our desperate minds impose on it.

Night in the Lonesome October by Zelazny. Also, Scream for Jeeves by Peter H. Cannon and And Another Thing by Eoin Colfer. Scream may not be the best ever, but it’s Bertie Wooster meets Lovecraft mythos. And Another Thing only has one, little bit, but who hasn’t wanted to see Cthulhu flunk a job interview?

Possibly because I haven’t read the story, I’m not finding Lovecraft’s xenophobia as bad as I might. I also have to admit to having been relatively shy as a kid and can easily transfer feelings of the being the new kid at school in a new town to some of what Lovecraft was feeling in New York. If you told me that one group of kids in particular grew up to worship the Elder Gods with Unspeakable Rites and Really Bad Music played Really Loud, it wouldn’t surprise me. . . .

OK, unlike Lovecraft, I felt like I had an obligation to adapt. Xenophobic fears and coping problems are understandable. Just don’t let them dominate your life. Find ways to deal with the world around you. When my great-grandma admitted to being scared of Indians, her father made a point of introducing her to several Indian ranch hands who worked in the area and let her shake hands with them.

Although, in Lovecraft’s defense, I’d like to point out New England is Red Sox territory and he was transplanted in the land of the Yankees. Give some people I know a choice between that and ghouls, and ghouls win every time. He also found at least one coping mechanism, pouring out his fears in fiction.

R. Emrys @@@@@ 27, oops, I missed this one, then.

Elynne @@@@@ 28, I’m not a big fan of Lovecraft’s racism, but I do relate with his loathing of New-York – not with the racist part, of course, but with the fear of huge soulless megapolis with too much speed, too much people and too much stress. It reminds me of Lorca’s Poet in New York: though two writers couldn’t have been more different, there is a lot of similarities in their reaction to the city. I would be very glad if some Lovecraftian writer created a crossover of their New York works.

Ellynne @28: It’s not as bad as Red Hook, but the whole introduction is “I thought it was a beautiful exotic city but it turns out to be FULL OF FOREIGNERS! Who don’t belong there! And speak LANGUAGES! And have no dreams!” New York is legitimately terrifying, overwhelming, overcrowded, and full of non-Euclidean angles (I say this as someone who likes the place)–but I’ve no sympathy for how he morphs this into the loss of some imaginary “true” city that belongs to the Right Kind of People.

Even aside from the doubtful suggestion that New York would be more itself without all these people from other places… Stories in which dreams are a precious, rare thing, that only a select few Dreamers are able to maintain, make me think of this XKCD.

Go your great-great-grandfather! And a good reminder that there was never some magically dreadful time when people were uniformly incapable of overcoming xenophobia.

Also, I think I may now mentally improve these stories by substituting “damn Yankees” for every one of Lovecraft’s nasty epithets about New Yorkers. I can get behind that!

I’m also a big fan of “Black Man with a Horn,” as well as Klein’s novel, The Ceremonies, and all the stories in Dark Gods.

In conjunction with reading SUPERNATURAL HORROR IN LITERATURE, it would be fun to read some of HPL’s favorites, as mentioned therein. Certainly Dunsany, Machen, Blackwood, M. R. James, E. F. Benson, others, lots of others.

Then there are all the concentric circles of Mythos writers, from the earliest to the latest! Who knows, maybe some of the living would make a guest appearance here!

When I have Howard to dinner with Jane Austen and, hmm, Hieronymous Bosch, I’ll ask him what in the worlds he thinks of his posthumous expansion through time. (Curwen & Co. are gathering the materials for saltes as we type.)

Public domain stuff that HPL loved and praised by name and that we might read:

Ambrose Bierce:

“The Damned Thing”

“The Death of Halpin Frayser”

F Marion Crawford:

“The Upper Berth”

“For the Blood is the Life”

Charlotte Perkins Gilman:

“The Yellow Wallpaper”

Mary Wilkins-Freeman:

“The Shadows on the Wall”

Wow – amazed that this thread has generated a reference to xkcd:Sheeple rather than xkcd:Wake Up Sheeple…

On that note, do I detect a touch of panic behind the denunciation of the NYC art scene? Imagine a delicate, artistic snowflake making the trek to Greenwich Village – only to witness thousands of delicate, artistic snowflakes struggling to make a living. In the end, HPL made a lasting mark – but the occasional morale-boosting exercise may have proved necessary (“Fools! I’ll show them all!”).

This seems like the thread in which to link to the Mountain Goats’ “Lovecraft In Brooklyn” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MrHgZRGLgo0), which is a) a perfectly respectable distillation of Lovecraft’s state of mind in NYC, b) a very good update of that sort of mindset and its logical consequences to the present day, and c) a decent Mythos story (suggestion? fragment?) in its own right.

Also, “woke up afraid of my own shadow / like, genuinely afraid” is one of the greatest song lyrics ever written.

I have a soft spot for “He”. It’s an actively terrible story, but the time-slip is so good. Also, the descriptions of probable Tsan-Chan always remind me of a perfectly lovely Hare Krishna procession I encountered once in Florence, leading me to think that the future city may be traumatizing only to people who aren’t much for music.

Oh, and you should absolutely go through and do ‘short stories discussed in Supernatural Horror in Literature‘. I read some incredibly brilliant things and some truly ludicrous dreck that way, and I promise that as a reading list it is the opposite of boring.

@14: Probably many in this forum know that Fritz Leiber not only wrote some Lovecraftian stories, but also composed essays about HPL, perhaps the best-known being “A Literary Copernicus,” published in 1949 in the Arkham House collection Something About Cats. Even today, this is a most perceptive and enjoyable summary of what Lovecraft’s work was about.

Speaking of Leiber, we should definitely read “To Arkham and the Stars”. I don’t know how findable it might be online, but it is a direct sequel to “Whisperer” in a way and deals with HPL himself. Same goes for Robert Bloch’s two stories that surround “Haunter of the Dark”. Also difficult to find, but these stories are in direct conversation with Lovecraft.

I should also have mentioned this a few weeks ago when we did our other media thread, but Lovecraft plays a secondary role in Paul Malmont’s delightfully weird and pulpy The Chinatown Death Cloud Peril.

@@@@@ # 8 : ‘Then you have the authors who inspired Lovecraft: William Hope Hodgson’s “House on the Borderland”…’ Quite a book, but where do you see its influence on Lovecraft?

@37: I can’t find a full legal version of “To Arkham and the Stars” online but I have it in the ebook of Writers of the Dark (Wildside Press), alongside several other Lovecraftian Leiber stories, Lovecraft’s letters to Leiber and several essays by Leiber, including the one mentioned @36.

@38: Lovecraft didn’t read Hodgson until 1934 but it made quite an impression when he did: Joshi cites The House on the Borderland as a potential influence on “The Shadow Out of Time” and Lovecraft added a passage on Hodgson to “Supernatural Horror in Literature”:

“The House on the Borderland (1908) — perhaps the greatest of all Mr. Hodgson’s works — tells of a lonely and evilly regarded house in Ireland which forms a focus for hideous otherworld forces and sustains a siege by blasphemous hybrid anomalies from a hidden abyss below. The wanderings of the Narrator’s spirit through limitless light-years of cosmic space and Kalpas of eternity, and its witnessing of the solar system’s final destruction, constitute something almost unique in standard literature. And everywhere there is manifest the author’s power to suggest vague, ambushed horrors in natural scenery. But for a few touches of commonplace sentimentality this book would be a classic of the first water.“

I would also like to see a review of Hodgson’s … eccentric far-future fantasy The Night Land, if enough re-readers are sufficiently brave.

Correction: I seem to have misread our story calendar. “Dreams in the Witch House” will be July 7th. This coming Tuesday, June 30th, we’ll look at Lovecraft and Bishop’s “The Curse of Yig.” Ophidiphobes beware. Fortunately for me and everyone else who’s catching up belatedly on this misprint, it’s quite short.

While the racism of “He” – like the racism of “The Horror at Red Hook” – REALLY upsets me, I can’t deny that I kind of like the notion of the Native Americans/First Nation Peoples taking revenge on the colonizers.

I currently live in NYC and used to live in Boston. I’m reasonably familiar with the Greenwich Village section of Manhattan and can comfortably say that Lovecraft’s description bears NO resemblance to the Greenwich Village I know. To me, it sounds like he is writing about Boston’s Back Bay or, more likely, the North End.

As far as recommendations for future review, how about one of Caitlin R. Kiernan’s mythos-themed short stories?

@39SchuylerH:” Lovecraft didn’t read Hodgson until 1934 but it made quite an impression when he did: Joshi cites The House on the Borderland as a potential influence on “The Shadow Out of Time””

Yeah, Joshi mentions that as a possibility in the entry on Hodgson in “The Lovecraft Encyclopedia,” but that would make it just one of several influences on the tale. In “Lovecraft: A Life” a life he he mentions HB Drake’s “The Shadowy Thing,” Beraud’s “Lazarus,” and the film “Berkeley Square” as the chief influences on “Shadow.”*

*He also notes that, contrary to some speculations, Stapledon’s “Last and First Men” was not an influence, as HPL did not read it until August of 1935, which was several months after he finished writing “Shadow out of Time.”

@42: I also doubt it was major but I will take any excuse to look at some Hodgson. I wonder what the effect of Hodgson and Stapledon’s cosmic visions would have been if Lovecraft had been able to build on them: I bet that if he could have held out a short while longer, he would have made it into the Campbell stable.

@SchuylerH, where can I find an ebook version of ‘Writers of the Dark’? I can only find the trade paperback and hardcover editions on Wildside’s site. Thanks!

@44: I found mine on Kobo: https://store.kobobooks.com/en-US/ebook/fritz-leiber-and-h-p-lovecraft-writers-of-the-dark.

I must have an unclean mind, but I kept thinking “rough trade”, or worse, when I read the beginning. Some older rich gent says “let’s come back to my place and I’ll show you some puppies secrets from beyond space and time”. Yep. Seems legit.

The fact that later the narrator is spotted in an alley, beaten up but not robbed,… yeah, that’s often what happens when out on a first date with Jeffrey Dahmer.

Yeah, anyone but Lovecraft I would have been *shocked* that it didn’t go there.

How about Neil Gaiman’s I, Cthulhu? It’s right here on Tor as well as on his own site, free to read for everyone.