Shadow demons plague the city reservoir, and Red King Consolidated has sent in Caleb Altemoc—casual gambler and professional risk manager—to cleanse the water for the sixteen million people of Dresediel Lex. At the scene of the crime, Caleb finds an alluring and clever cliff runner, Crazy Mal, who easily outpaces him.

But Caleb has more than the demon infestation, Mal, or job security to worry about when he discovers that his father—the last priest of the old gods and leader of the True Quechal terrorists—has broken into his home and is wanted in connection to the attacks on the water supply. From the beginning, Caleb and Mal are bound by lust, Craft, and chance, as both play a dangerous game where gods and people are pawns. They sleep on water, they dance in fire…and all the while the Twin Serpents slumbering beneath the earth are stirring, and they are hungry.

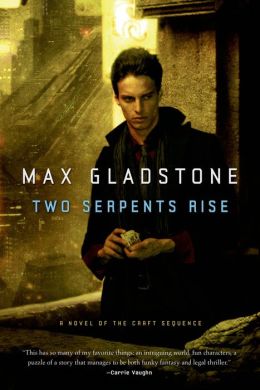

We’re pleased to present an extended excerpt from Two Serpents Rise, chronologically the second book in Max Gladstone’s Craft Sequence. Set about 20 years after the events of Last First Snow, the novel begins with a goddess, and a card game…

1

The goddess leaned over the card table and whispered, “Go all in.”

She hovered before Caleb, cloudy and diaphanous, then cold and clear as desert stars. Her body swelled beneath garments of fog: a sea rock where ships dashed to pieces.

Caleb tore his gaze away, but could not ignore her scent, or the susurrus of her breath. He groped for his whiskey, found it, drank.

The cards on the green felt table were night ladies, treacherous and sweet. Two queens rested facedown by his hand, her majesty of cups (blond, voluptuous, pouring blood and water from a chalice), and her majesty of swords (a forbidding Quechal woman with broad face and large eyes, who gripped a severed head by the hair). He did not have to look to know them. They were his old friends, and enemies.

His opponents watched: a round Quechal man whose thick neck strained against his bolo tie, a rot-skinned Craftsman, a woman all in black with a cliff’s face, a towering four-armed creature made from silver thorns. How long had they waited?

A few seconds, he thought, a handful of heartbeats. Don’t let them rush you.

Don’t dawdle, either.

The goddess caressed the inner chambers of his mind. “All in,” she repeated, smiling.

Sorry, he thought, and slid three blue chips into the center of the table.

Life faded from him, and joy, and hope. A part of his soul flowed into the game, into the goddess. He saw the world through her eyes, energy and form flowering only to wilt.

“Raise,” he said.

She mocked him with a smile, and turned to the next player.

Five cards lay faceup before the dealer. Another queen, of staves, greeted the rising sun in sky-clad silhouette—a great lady, greater still when set beside his pair. To her right the king of swords, grim specter, stood knife in hand beside a struggling, crying child bound upon an altar. The other cards struck less dramatic figures, the eight and three of staves, the four of coins.

Three queens formed a strong hand, but any two staves could make a flush, and beat him.

“Call,” said the man in the bolo tie.

“Call,” said the Craftsman with the rotting skin.

“I see your raise,” said the woman, “and raise you two thousand.” She pushed twenty blue chips into the pot. The goddess whirled, a tornado of desire, calling them all to death.

“Fold,” said the creature of thorns.

The goddess turned again to Caleb.

Did the woman in black have a flush, or was she bluffing? A bluff would be brash against three other players with a possible flush on the board, but Caleb’s had been the only bet this round. Would she risk so much on the chance she could drive three players to fold?

Calling her bluff would take his whole reserve. He’d have to give himself to the game, hold nothing back.

The goddess opened her mouth. The black within yawned hungrily. Perfection glinted off the points of her teeth.

You can win the world, she said, if you’re willing to lose your soul.

He looked her in the eye and said, “Fold.”

She laughed, and did not stop until the black-clad woman turned over her cards to reveal a king and a two, unsuited.

Caleb bowed his head in congratulations, and asked the others’ leave to go.

* * *

Caleb bought another drink and climbed marble stairs to the pyramid’s roof. Dandies, dilettantes, and high-society corpses clustered near the edge, glorying in the panorama of Dresediel Lex by night: gleaming pyramid-studded city, skyspires adrift like crystal scimitars above, the ceaseless roll of the Pax against the western shore. A ceiling of low clouds confronted the metropolis with its own reflected light.

Caleb was not interested in the view.

A carved black stone altar rose from the center of the roof, large enough to hold a reclining man, or woman, or child. From the iron fence around the altar hung a bronze plaque embossed with a list of dates and victims’ names.

He didn’t read the plaque. He knew too much history already. He leaned against the railing, and watched the old altar. Dew rolled down his whiskey glass and wet his hand.

Teo found him twenty minutes later.

He heard her approach from the stairwell. He recognized her stride.

“It’s been a long time,” she said, “since I’ve seen you leave a game that fast. Not since school, I think.”

“I was bored.”

In modest heels, Teo was Caleb’s height and broader, built of curves and arches. Her lips were full, her eyes dark. Black ringlets framed her round face. She wore white pants with gray pinstripes, a white vest, a ruby shirt, a gray tie, and an expression of concern. Her hand lacked a drink.

She joined him at the rail.

“You weren’t bored.” She turned her back on the altar, and looked east over the city, toward the gleaming villas atop the Drakspine ridge. “I don’t know how you can spend so much time staring at that old rock.”

“I don’t know how you can look away.”

“It’s bad art. Mid-seventh dynasty knockoff, gaudy and overornamented. Aquel and Achal on the side look more like caterpillars than snakes. They didn’t even sacrifice people here often. Most of that happened over at our office.” She pointed to the tallest pyramid on the skyline, the immense obsidian edifice at 667 Sansilva. Caleb’s father would have called the building Quechaltan, Heart of the Quechal. These days it had no name. “This place did cows. The occasional goat. People only on an eclipse.”

Caleb glanced over his shoulder. Dresediel Lex sprawled below: fifteen thousand miles of roads gleaming with ghostlight and gas lamps. Between boulevards crouched the houses and shops and apartment buildings, bars and banks, theaters and factories and restaurants, where seventeen million people drank and loved and danced and worked and died.

He looked away. “We have an eclipse every year, a partial or a lunar. For a full solar like the one this autumn, the priests would work through all the prisoners and captives they could find, throw in a few innocents for good measure. Blood and hearts for Aquel and Achal.”

“And you wonder why I don’t look? It’s bad art, and worse history. I don’t know why Andrej”—the bar’s owner—“keeps it around.”

“You wouldn’t have thought that way seventy years ago.”

“I like to think I would have.”

“So would I. But your grandparents, and my father, they weren’t born different from the rest of us, and they still fought tooth and claw to defend their gods back in the Wars.”

“Yeah, and they lost.”

“They lost, our boss won, kicked out priests and pantheon, and now we all pretend three thousand years of bloodshed didn’t happen. We put a fence around history and hang a plaque and assume it’s over. Try to forget.”

“What’s put you in such a good mood?”

“It’s been a long day. Long week. Long year.”

“Why did you fold, at the table?”

“I catch hell from the goddess, and I need to explain myself to you, too?”

“The goddess doesn’t know you like I do. She’s reborn every game. I’ve watched you play for eight years, and I’ve never seen you cave like that.”

“The odds were against me.”

“Screw odds. You had to know the lady in black wasn’t suited.” He turned from the altar. Southwest winds bore the sea scent of salt and death. “Can’t you go stalk some girl fresh from university or something? Leave me in peace?”

“I’m reformed. I am no longer a dirty old woman.”

“Could have fooled me.”

“Seriously, Caleb. What’s wrong?”

“Nothing,” he said, and patted his pockets for a smoke. Of course nothing. He quit years ago. Bad for his health, the doctors said. “The odds were against me. I wanted to get out with my soul intact.”

“You wouldn’t have done that four years ago.”

“A lot changes in four years.” Four years ago, he was a fledgling risk manager at Red King Consolidated, recovering from a university career of cards and higher math. Four years ago, he was dating Leah. Four years ago, Teo still believed she was interested in boys. Four years ago, he’d thought the city had a future.

“Yes.” A tiny copper coin lay at Teo’s feet, a bit of someone’s soul spooled up inside. She kicked the coin, and it tinged across the roof. “Question is, whether the change is for the better.”

“I’m tired, Teo.”

“Of course you’re tired. It’s midnight, and we’re not twentytwo anymore. Now get down there, apologize to that table, and steal their souls.”

He smiled, and shook his head, and collapsed, screaming.

Images burrowed into his brain: blood smeared over concrete, a tangled road into deep mountains, the chemical stench of a poisoned lake. Teeth gleamed in moonlight and tore his flesh.

Caleb woke to find himself splayed on the sandstone floor. Teo bent over him, brow furrowed, one hand cool against his forehead. “Are you okay?”

“Office call. Give me a second.”

She recognized the symptoms. If necromancy was an art, and alchemy a science, then direct memory transfer was surgery with a blunt instrument: painful and unsubtle, dangerous as it was effective. “What does the boss want with you at midnight?”

“I have to go.”

“Hells with her. Until nine tomorrow, the world is someone else’s responsibility.”

He accepted her hand and pulled himself upright. “There’s a problem at Bright Mirror.”

“What kind of problem?”

“The kind with teeth.”

Teo closed her mouth, stepped back, and waited.

When he could trust his feet, he staggered toward the stairs. She caught up with him at the stairwell.

“I’m coming with you.”

“Stay here. Have fun. One of us should.”

“You need someone to look after you. And I wasn’t having fun anyway.”

He was too tired to argue as she followed him down.

2

Moonlight shone off the streak of blood on the concrete path beside Bright Mirror Reservoir.

Caleb watched the blood, and waited.

The first Wardens on site had treated the guard’s death as a homicide. They scoured the scene, dusted for fingerprints, took notes, and asked about motive and opportunity, weapons and enemies—all the wrong questions.

When they found the monsters, they began to ask the right ones. Then they called for help.

Help, in this case, meant Red King Consolidated, and, specifically, Caleb.

Dresediel Lex had been built between desert and sea by settlers who neither expected nor imagined their dry land would one day support seventeen million people. Down the centuries, as the city grew, its gods used blessed rains to fill the gaps between water demand and supply. After the God Wars were won (or lost, depending on who you asked), RKC took over for the fallen pantheon. Some of its employees laid pipe, some built dams, some worked at Bay Station maintaining the torturous Craft that stripped salt from ocean water.

Some, like Caleb, solved problems.

Caleb was the highest-ranking employee on site so far. He had expected senior management to swoop in and take charge of a case like this, with death and property damage and workplace safety at issue, but his superiors seemed intent to leave Bright Mirror to him. At the inevitable inquest, he would be the one called to testify before Deathless Kings and their pitiless ministers.

The RKC brass had given him a wonderful opportunity to fail.

He wanted a drink, but could not afford to take one.

For a frenzied half hour, he’d ordered junior analysts and technicians through the routines of incident response. Isolate the reservoir from the city mains. Pull some Craftsmen out of bed to build a shield over the water. Find a few tons of rowan wood, stat. Check the dam’s wards. Cordon off the access road. No one comes in or out.

Orders given, he stood, silent, by the blood and the water.

Glyphs necklaced Bright Mirror Reservoir in blue light. The dammed river ran glossy black from shore to shore. He smelled cement, space, the broad flatness of still water, and above all that a sharp ammonia stench.

Two hours ago, a security guard named Halhuatl had walked along the reservoir, casting about in the dark with a bull’s-eye lantern. Hearing a splash, he stepped forward. He saw nothing—no night bird, no bat, no swimming coyote or bathing snake. He scanned the water with his lantern. Where the light touched, it left a rippling trail.

That’s strange, Hal must have thought, before he died.

A chill wind blew over the water, producing no waves. Caleb stuck his hands deep into the pockets of his overcoat. Footsteps approached.

“I grabbed this from the icebox in the maintenance shack,” Teo said, behind him. “The foreman will miss his lunch tomorrow.”

He turned from the water and reached for the parcel she held, white wax paper tied with twine. “Thank you.”

She didn’t let go. “Why do you need this?”

“To show you what’s at stake.”

“Funny.” She released the package. He undid the twine with his gloved hands, and opened the paper. A frost-dusted slab of beef lay within, its juice the same color as the blood on the concrete.

He judged the distance to the water, lifted the beef, and threw it overhand.

The meat arced toward the reservoir. Beneath, water bulged and reared—a wriggling, viscous column rippled with reflected stars.

The water opened its mouth. Thousands of long, curved fangs, stiletto-sharp, snapped shut upon the beef, piercing, slicing, grinding as they chewed.

The water serpent hissed, lashed the night air with an icy tongue, and retreated into the reservoir. It left no trace save a sharper edge to the ammonia smell.

“Hells,” Teo said. “Knife and bone and all the hells. You weren’t kidding about teeth.”

“No.”

“What is that thing?”

“Tzimet.” He said the word like a curse.

“I’ve seen demons. That’s no demon.”

“It’s not a demon. But it’s like a demon.”

“Qet’s body and Ilana’s blood.” Teo was not a religious woman—few people were religious any more, since the God Wars—but the old ways had the best curses. “That thing’s living in our water.”

Her voice held two levels of revulsion. Anyone could have heard the first, the common terror. Only someone who knew how seriously Teo took her work with Red King Consolidated would detect her emphasis on the word “our.”

“No.” Caleb knelt and wiped the meat juice off his gloved fingers onto the ground. “It’s not in our water. It is our water.” Stars glared down from the velvet sky. “We’ve isolated Bright Mirror, but we need to check the other reservoirs. Tzimet grow slowly, and they’re clever. They could be hiding until they’re ready to strike. It’s blind luck we caught this one.”

“What do you mean, it is the water?”

“The Craft keeps our reservoirs clean: wards against germs, fish, Scorpionkind larvae, anything that might pollute or corrupt. Charms to curb evaporation. The reservoir’s deep, with dark shadows at the bottom. When the sun and stars shine, a border forms between light and darkness. The Craft presses against that border. If there’s enough pressure, it pokes a tiny hole in the world.” He held his thumb and forefinger an inch apart. “Nothing physical can fit through, only patterns. That’s what these Tzimet are.” He pointed to the reservoir. “Like seed crystals. A bit of living night seeps into the water, and the water becomes part of the night.”

“I’ve never seen a crystal with teeth.” She paused, corrected herself. “Outside of a gallery. But that one didn’t move.” She pointed to the blood. “Who was it?”

“Security guard. Night roster says the guy’s name was Halhuatl. The Wardens thought this was a homicide until the reservoir tried to eat them.”

Gravel growled on the road behind: the golem-carts arrived at last. Caleb turned. Exhaust puffed from joints in the golems’ legs. RKC workers in gray uniform jackets walked from cart to cart, checking the rowan logs piled within. Two junior analysts stood beside the foreman, taking notes. Good. The workers knew their business. They didn’t need his people interfering.

“Horrible way to die,” Teo said.

“Quick,” Caleb answered. “But, yes.”

“Poor bastard.”

“Yeah.”

“Now we know Tzimet are in there, we can keep them from getting out. Right?”

“They can’t get into the water system, but to keep them imprisoned we need better Craftsmen than we’ve been able to get out here so far. Those glowing glyphs hide the reservoir from animals that want a drink. We’ve inverted them to hide the outside world from the Tzimet. They can’t hear us or smell us, but they could kill us no problem if they knew we were here.”

“You sure know how to make a lady feel safe.”

“The Craft division’s woken Markoff, Billsman, and Telec; once they arrive, they’ll build a shield over the water. Feel safe then.”

“No way Telec’s sober enough for work at this time of night. And Markoff will be trying to impress the shorefront girls with his rich-and-sinister routine.”

“Dispatch found them all, and claims they’re up for it. Anyway, the Tzimet aren’t a big deal in the meantime, long as they don’t get into the pipes.”

“Glad to hear it.” She grimaced. “I think I’ll lay off tap water all the same.”

“Don’t let the boss catch you.”

“I said I’d stop drinking it, not selling it. Can this kind of infection happen any time?”

“Technically?” He nodded. “The odds of Tzimet infestation in a given year are a hundred thousand to one against or so. We didn’t expect anything like this for at least another century. Poison, bacterial blooms, Scorpionkind, yes. Not this.”

“So you don’t think it was natural?”

“Might have been. Or someone might have helped nature along. Good odds on the latter.”

“You live in a grim universe.”

“That’s risk management for you. Anything that can go wrong, will—with a set probability given certain assumptions. We tell you how to fix it, and what you should have done to keep it from happening in the first place. At times like these, I become a hindsight professional.” He pointed at the blood. “We ran the numbers when Bright Mirror was built, forty-four years ago, and thought the risks were acceptable. I wonder if the King in Red will break the news to Hal’s family. If he has a family.”

“The boss isn’t a comforting figure.”

“I suppose not.” A line of golem-carts rolled past behind them.

“Can you imagine it? A knock, and you answer the door to see a giant skeleton in red robes? With that flying lizard of his coiled on your lawn, eating your dog?”

“There would be heart attacks.” Caleb couldn’t resist a slim smile. “People dying with the door half open. Every personal injury Craftsman in the city would descend on us like sharks when blood’s in the water.”

Teo clapped him on the shoulder. “Look who’s got his sense of humor back.”

“I might as well laugh. I have another three hours or so of this.” He waved over his shoulder at the carts with their cargo. A bleary brigade of revenants in maintenance jumpsuits lurched by, bearing rowan. They stank of grave-musk. “I won’t leave until three, maybe four.”

“Should I be worried that it takes demons to break you out of your funk?”

“Everyone likes to be needed,” he said. “I might be late to work tomorrow.”

“I’ll tell Tollan and the boys you were out keeping the world safe for tyranny.” She fished her watch out of her pocket, and frowned.

“You late for something?”

“A little.” She closed the watch with a click. “It’s not important.”

“I’m fine. I’ll catch up with you tomorrow.”

“You’re sure? I can stay here if you need me.”

“Fate of the city on the line here. I have my hands full. No room for self-pity. Go meet your girl.”

“How did you know there was a girl?”

“Who else would be waiting for you at two in the morning? Go. Don’t get in trouble on my account.” “You better not be lying.”

“You’d know if I was.”

She laughed, and retreated into the night.

* * *

The maintenance crew poured ten tons of rowan logs into the reservoir. Revenants did most of the hands-on work, since they smelled less appetizing to the Tzimet. Soon, a smooth layer of wood covered the water. Caleb thanked the foreman as his people slunk back to their beds.

The rowan would block all light from stars and moon and sun. The wood’s virtue poisoned Tzimet, and deprived of the light that cast their shadows, the creatures would wither and die.

Overhead, Wardens circled on their Couatl mounts. Heavy feathered wings beat fear through the sky, and Caleb felt serpents’ eyes upon him.

By sunrise, every executive in Red King Consolidated would be knocking on Caleb’s door, demanding to know how Bright Mirror was corrupted. Craftsmen could bend lightning to their will, cross oceans without aid, break gods in single combat, but they remained human enough to hunt scapegoats in a crisis. Sixty years after Dresediel Lex cast off the gods’ yolk, its masters still demanded blood.

So Caleb searched for a cause. Bright Mirror had been built with safeguards upon safeguards. If a mistake was made, what mistake, and who made it? Or was there some force at work more sinister than accident? The True Quechal, or another group of god-worshipper terrorists? Rival Concerns, hoping to unseat Red King Consolidated as the city’s water source? Demons? (Unlikely— the demon lords made a hefty profit from their trade with Dresediel Lex, and had no reason to hurt the city.)

Who would suffer for Halhuatl’s death?

Rowan logs bobbed on the still reservoir. Caleb’s footsteps were the only breaches in the night’s silent shell. City lights glowed over the dam’s edge, as if the world beyond was burning.

He walked the shoreline, searching for a sacrifice.

3

By the time Caleb reached the far side of the reservoir, he was so exhausted he almost didn’t see the woman.

He had not found his cause. All the equipment and wards seemed to work. No barbed wire was severed, no holes cut into the fence. No drums of poison stood empty beside decaying chemical sheds. He spied no pitons or carved handholds on the cliffs above the water.

When he closed his eyes and examined Bright Mirror as a Craftsman would, he saw an enormous web spun in three dimensions by a drunken spider. He could make no sense of that weave, let alone tell if it was broken.

He opened his eyes again. The dam’s edge cut the world in half, water and rowan below and sky above. To his right stood a dormitory shack, windows dark, inhabitants lost in sleep and demon dreams. Caleb was alone.

He blinked.

Not alone.

A woman leaned against the shack, arms crossed, one knee bent, her heel resting on the wall.

She did not seem to have noticed him. He engraved her on his memory: slender, and tense as a bent blade. Short black flames of hair blazed from her head. Thin lips, with sharp edges. She wore calf-length pants the color of sand and rock, a white sleeveless shirt, and dark gray close-toed sandals with leather straps that wrapped around her ankles and calves. She looked as if she had no business anywhere near Bright Mirror Reservoir.

She rubbed her bare arms, and shivered from the cold.

Either the woman had not seen him, or didn’t think he could see her. If the former, she’d see him soon enough; if the latter, no sense demonstrating she was wrong. He surveyed grounds, sky, water, and shed, as if she did not exist. Step by nonchalant step, he drew closer. She glanced at him, and smiled a self-satisfied smile. She did not greet him, nor did she speak, which settled the matter to Caleb’s satisfaction. She thought she was invisible. Fair enough.

When he came within range, he sprang.

He pinned her arms to the wall. She did not curse or struggle, only stared at him with wide startled eyes of a brighter black than he’d known eyes could be.

He was lucky, he realized, that she didn’t try to fight him. Her arms felt strong, and his groin was exposed to her knee.

“Who,” she asked, “are you?”

“That’s my line.”

“You don’t look like a Warden. Is this your hobby, jumping unarmed women in the middle of the night?”

“What are you doing here?”

“I’m taking the air,” she said with a smile. “Waiting for a nice man to accost me. Only way to get a date in this town.”

“Give me a straight answer.”

“I fell from the sky.” She was beautiful, he thought, as weapons were beautiful. No. Focus.

“I work for RKC. This reservoir has been poisoned. The water’s infested with Tzimet. One of our workers is dead. I’m not here to joke.”

Her smile broke. “I’m sorry.”

“Who are you?”

“You first.”

“I’m Caleb Altemoc,” he said before it occurred to him not to answer.

“You can call me Mal,” she said. “I’m a cliff runner.” Caleb’s eyebrows rose. The rules of cliff running were as simple as the rules of murder: runners chose a starting rooftop and a destination, and met at moonrise to race, following any path they chose so long as their feet never touched ground. “I train in these mountains at night. I’ve come every evening for a couple months, but usually no one’s awake. Between the Wardens, the zombies, and the carts, I had to stop and watch.”

“Months. Why haven’t we caught you before now?”

Her eyes flicked down. A shark’s tooth pendant hung from a cord around her neck. The tooth was etched with the Quechal glyph for “eye,” capped by a double arc that signified denial or falsehood. Eye and arc both glowed with soft green light. A strong ward against detection. Expensive, but cliff running was a sport for idiots, madmen, and people who could afford good doctors.

“Why should I believe you?”

“If I’d poisoned this water, would I wait around for someone to discover me?”

“That’s for the Wardens to decide.”

“I haven’t done anything wrong.”

“Trespassing is wrong. And they’ll want to talk to you even if you’re innocent. If you’ve been here every night for the past few months, you might have seen something that could help us.”

“I won’t go with the Wardens.” She pushed against his grip, to test him. He did not release her, and shifted to the side to bring his groin out of range. “You know how they feel about cliff runners. Ask me what you want, but keep them out of it.”

“I’m sorry.”

“I’m sorry, too,” she said, and hit him in the face with her forehead.

Caleb stumbled, and caught himself against brick. Blind, he turned, following her footfalls. His vision cleared in time to see her leap out over the reservoir. He cried a warning she did not seem to hear.

Claws of black water burst up to pierce and catch and rend. She fell between them all, landed on a thick rowan log, and sprang from it to the next. Talons sliced through the air behind her. Mal fled toward the dam, trailing a wake of hungry mouths.

Caleb had no time to call after her. Four thorn-tipped columns rose from the water, arched above him, and descended. He dodged right, hit the ground hard, lurched to his feet and sprinted along the water’s edge. The Tzimet could not see him, but they knew humans: where one was, others would be also.

Out of the corner of his eye he saw Mal run and leap, now an arc, now a vector.

He did not wonder at her, because he had no time. He ran with fear-born speed.

Iron stairs led down to catwalks crisscrossing the dam’s face. Caleb reached the stairs seconds ahead of the Tzimet, clattered down the first flight, and crouched low on the landing. The dam plummeted three hundred feet beneath him to a broad valley of orange groves. Miles away, Dresediel Lex burned like an offering to angry, absent gods. He pushed all thoughts of height and falling from his mind. The iron landing, the dam, these were his world.

Wards at the dam’s crest stopped floods during the winter rains. They should hold the Tzimet.

Emphasis on “should.”

He swore. Mal (if that was her real name) was his best lead, and she’d be dead soon, if she wasn’t already. One misstep, a log rolling wrong underfoot, and she would fall into a demon’s mouth.

He waited for her screams.

A scream did come—but a scream of frustration, not pain, and issued from no human throat.

Mal dove off the dam into empty space.

Once, twice, she somersaulted, falling ten feet, fifteen. Caleb’s stomach sank. She fell, or flew, without sound.

Twenty feet down, she snapped to a midair stop and dangled, nose inches from the dam’s pebbled concrete face. A harness girded her hips, and a long thin cord ran from that harness to the crest of the dam.

Blue light flared above as Tzimet strained against the wards. Iron groaned and tore. A claw raked over the dam’s edge. Lightning crackled at its tip.

Mal pushed off the concrete and began to sway like a pendulum, reaching for the nearest catwalk—one level down from Caleb. He ran to the stairs. Another talon pressed through the dam wards, scraping, seeking.

At the apex of Mal’s next swing, he strained for her. She clasped a calloused hand around his wrist, pulled herself to him, wrapped a leg around the catwalk’s railing, and unhooked her tether.

“Thanks,” she said. Sparks showered upon them. Fire and Craft-light lanced in her eyes.

“You’re insane.”

“So I’ve heard,” she said, and smiled, and let go of his arm. He grabbed for her, too slowly. She fell—ten feet back and down, to roll and land on a lower catwalk, stand, run, and leap again. She accelerated, jumping from ledge to ledge until she reached the two-hundred-yard ladder to the valley floor.

Caleb climbed over the railing to follow her, but the chasm clenched his stomach. His legs quaked. He retreated from the edge.

Above, demons clawed at the emptiness that bound them.

The Wardens would catch her in the valley, he told himself, knowing they would not. She was already gone.

4

An hour and a half later, a driverless carriage deposited Caleb on the corner of Sansilva Boulevard and Bloodletter’s Street, beside a jewelry shop and a closed coffee house. He hurt. Adrenaline’s tide receded to reveal pits of exhaustion, pain, and shock. He’d told the Wardens he was fine, he’d make it home on his own, thanks for the concern, but these were lies. He was a good liar.

Broad streets stretched vacant on all sides. The carriage rattled off down the empty road. Night wind brushed his hair, tried and failed to wrap him in a comforting embrace.

He remembered lightning-lit eyes, and a tan body falling.

He’d given the carriage the wrong address, and stumbled a block and a half to his destination, a ten-story metal pyramid built by an Iskari architect mimicking Quechal designs. Over the door, a plaque bore the building’s name in an art deco perversion of High Quechal script: the House of Seven Stars.

He exhaled. It was this, or home.

“You’ve come up in the world,” said a voice behind him, deep as the foundations of the earth.

Caleb closed his eyes, gritted his teeth, and counted in his head to ten and back in Low Quechal, High Quechal, and common Kathic. By the time he finished (four, three, two, one), the flare of anger dulled to a familiar, smoldering rage. His nails bit into his palms. Perfect ending to a perfect day.

“Hi, Dad,” he said.

“Either that, or you’ve abandoned that rat-trap house in the Vale to live off your friends until they kick you out.”

“It’s a long way home. I’ve been working.”

“You shouldn’t work so late.”

“Yeah,” Caleb said. “I shouldn’t. I wouldn’t have to, either, if you’d stop trying to kill people.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Caleb turned around.

Temoc towered in the darkness beyond the streetlamps. He was a man built on a different scale from other men: torso like an inverted pyramid, arms as thick as his legs, a neck that sloped out to meld with his shoulders. His skin was a black cutout illuminated by glowing silver scars. The same shadows that clouded his body obscured his features, but Caleb would have known him anywhere: last of the Eagle Knights, High Priest of the Sun, Chosen of the Old Gods. Scourge of the Craftsmen and right-thinking folk of Dresediel Lex. Fugitive. Terrorist. Father.

“You’re telling me you don’t know anything about Bright Mirror.”

“I know the place,” Temoc said. “What has happened there?”

“Don’t play dumb with me, Dad.”

“I play at nothing.”

“Tzimet got into the reservoir. We’re lucky they killed a security guard before the water cycled into the mains this morning. Otherwise we’d have thousands out already, crawling in people’s mouths, spearing them from the inside.”

Temoc frowned. “Do you think I would do that? Consort with demons, endanger the city?”

“Maybe not. But your people might.”

“We stand up for our religious rights. We resist oppression. We do not murder innocents.”

“Bullshit.”

Temoc lowered his head. “I do not like your tone.”

“What about when you ambushed the King in Red five months back?”

“Your… boss… broke Qet Sea-Lord on His own altar. He impaled Gods on a tree of lightning, and laughed as They twitched in pain. He deserves seventeen-fold vengeance. I am the last priest of the old ways. If I do not avenge, who will?”

“You attacked him in broad daylight, with thunder and shadow and incendiary grenades. People died. He survived. You knew he would. No one who can kill gods would go down that easily. All you did was hurt the innocent.”

“No one who works for Red King Consolidated is wholly innocent.”

“I work for RKC, Dad.”

An airbus passed overhead. Light from its windows cast the pavement in alternating strips of brilliance and shade. The light revealed Temoc’s face in slivers: jutting cliff of jaw, heavy brow, dark, deep eyes, Caleb’s own broad nose. A dusting of white at his temples, and the firm lines chiseled into cheeks and forehead, were his only signs of age. No man in Dresediel Lex could say how old Temoc was, not even his son—he had been a hale young knight when the gods fell, which made him eighty at least. He nurtured the surviving gods, and they kept him young, and strong. He was all they had left—and for twenty years, they had been his only companions.

Caleb looked away. His eyes burned, and his mouth felt dry. He massaged his forehead. “Look, I’m sorry. It’s been a long night. I’m not at my, I mean, neither of us is at his best. You say you don’t have anything to do with the Bright Mirror thing?”

“Yes.”

“If you’re lying, we’ll find out.”

“I do not lie.”

Tell that to Mom, he could have said, but didn’t. “Why are you here?”

Caleb’s father might have been a statue for how little he moved—a bas relief in one of the temples where he had prayed before the God Wars, where he prayed and cut his arms and legs and dreamed that one day he would tear a man’s heart from his chest and feed it to the Serpents. “I worry about you,” he said. “You have been staying out late. Not sleeping enough. Gambling.”

Caleb stared at Temoc. He wanted to laugh, or to cry, but neither impulse won out, so he did nothing.

“You should take better care of yourself.”

“Thanks, Dad,” he said.

“I worry about you.”

Yes, Caleb thought. You worry about me in those last raw hours before nightfall, before you try to tear down everything we who work in this city build during the day. You worry about me, because there’s no more priesthood, and what are kids to do these days when there are no more reliable careers involving knives, altars, and bleeding victims? “That makes two of us,” he said, and: “Look, I have to go. I have work in four hours. Can we talk about this later?”

No response.

He turned back to his father, to apologize or to curse, but Temoc was gone. Wind blew down Bloodletter’s Street from the ocean and sent a small flock of discarded newspapers flapping into the night: gray beasts old the moment they were made.

“I hate it when he does that,” Caleb said to nobody in particular, and limped across the street to the House of Seven Stars.

* * *

Teo had an apartment on the seventh floor, a corner room she’d bought with her own soulstuff. The day she signed the contract she’d drunk a half-gallon of gin with Caleb in celebration. “Mine. Not my father’s, not my mother’s, not my family’s. My soul, my house.” When he observed that she was technically part of her family, she’d thrown a napkin at him and called him a bastard.

“You know what I mean. My cousins are all tied to the purse strings. Not one of them has even the poorest excuse for a career. They live in those damn beach houses up the coast, or circle the globe on Pop’s ticket, three weeks doing coke off the naked back of an eighteen-year-old boy in one of those nameless ports south of the Shining Empire, a month ogling sentient ice sculptures in Koschei’s kingdom. Lunch in Iskar, dinner in Camlaan, a romp in the Pleasure Quarters of Alt Coulumb, and none of it earned. This place, this is mine.” She put a fierce edge on that word.

“And what’s yours,” Caleb replied, drink-slurred, “is mine.”

“I’ll hang the most absurd pictures on the wall, and keep a shelf of single malts, and polish the counters so they reflect themselves a hundred million times. Never will there be a single book out of place or a single picture crooked.”

She was drunk, too.

“Can I visit?”

“You may call on me for the occasional bacchanal and revel.” She glared down her nose at him like an empress from her throne. “In exchange, if I am out of town on business, you must feed Compton,” meaning her cat, a treacherous calico.

“Sure,” he said, and took the key she offered.

He leaned against the lift wall and watched the floor numbers tick up to seven. Phantoms filled his skull: Temoc, father, rebel, murderer, saint. The goddess whispered in his ear. Blood. Stars reflected in dark water. They all faded into vacant, expansive night, the night after the death of the world.

The night of his mind shone black. Mal curved before him like a blade.

The lift’s bell called Caleb back from the ocean of her eyes to a white-carpeted hallway hung with dull oil paintings. Vases of silk flowers stood on teak tables heavy with ornamental bronze. He shuffled down the hall, and searched his jacket pockets for Teo’s key.

His thoughts were chaos and blood and fire as he slid the key into the lock. Chaos, blood, and fire; flood, poison, riot, ruin. Mal didn’t seem the poisoning type, but what was the poisoning type? Why linger at Bright Mirror if she wasn’t involved? She should have snuck away the moment she saw Wardens. Perhaps she trusted her shark’s tooth to keep her safe. Flimsy defense, since Caleb could see her. Then again, the Wardens lacked Caleb’s scars.

He needed a bed, or a comfortable couch. He’d catch hell from Teo in the morning for stumbling in unannounced, but her apartment was closer to the office than his, and he had stashed clothes in her closet—clubbing clothes, yes, but he could salvage an outfit from them for work.

He pushed the key home, turned the knob.

Light stung his eyes, and for a confused moment he thought, good, Teo’s still awake. He stepped into the living room.

Thirty seconds and a shriek later he staggered, eyes closed, out into the hallway. The door slammed behind him. His cheeks burned. From within, he heard two women’s voices raised in argument. He waited, eyes still shut, until Teo’s words assumed the weight of finality, and the other woman retreated toward the bedroom, cursing.

The latch turned and the door opened.

“You can look now,” Teo said.

She’d wrapped herself in a plush white bathrobe, hair a tangled mass on her forehead. Compton wound sinuously between her bare feet, and licked sweat from her ankles. Over Teo’s left shoulder, Caleb saw a blonde wearing white cotton briefs and nothing else stagger into the apartment’s one bedroom and slam the door. “She seems nice,” he said, lamely. Teo didn’t respond. He tried again: “Sorry. I’ll go.”

She assessed him with a glance: clothes in disarray, hair standing up, tie crooked and loose. “What happened?”

“The Bright Mirror thing went south. There was a girl there, and she woke the Tzimet up. I have to be in the office early, but I need sleep. Hoped I could use your couch.” I didn’t realize you were using it, he thought but didn’t say. “Sorry. Dumb idea.” He didn’t want to go home. “I hope I didn’t screw up anything for you.”

She sighed. “You didn’t screw anything up. Quite the opposite, in fact.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Don’t worry about it. Sam’s emotional. An artist. She’ll be fine in the morning. The couch is yours, if you want it.”

“I shouldn’t.”

“I can’t let you stumble back out into the night looking like a half-strangled puppy. I’ll tell her you’re one of my idiot cousins or something. Don’t make me regret it.”

“Too late,” he said, but she had already turned her back on him.

Lights off, he lay on Teo’s couch in the dark, staring up at the terrifying cubist landscapes that adorned her living room. A panorama of the Battle of Dresediel Lex hung over the couch, burning pyramids and torn sky, spears of flame and ice, bodies impaled on moonlight sickles, warring gods and Craftsmen rendered in vivid scrolls of paint. One corner of the painting showed Temoc locked in single combat with the King in Red, before he fell.

Caleb’s eyes drifted shut. Tzimet towered above him, reaching toward the cold stars. Compton dug claws into his leg. He rolled onto his side. Leather creaked.

He drifted to sleep, drowning in a black sea.

Excerpted from Two Serpents Rise © Max Gladstone, 2013