No one gives voice to monsters and misfits quite as well as author Clive Barker. Since his short fiction first bled across the genre landscape thirty years ago, he has become synonymous with a particularly beautiful and horrific brand of dark fantasy. He’s enjoying a bit of a cultural revival this year thanks to the releases of the long-awaited final novel in the Hellraiser universe and the equally anticipated director’s cut edition of his cult film, Nightbreed.

Nightbreed and the novella it was adapted from, Cabal, are so enduring, editors Joe Nassise and Del Howison have just released Midian Unmade, an anthology of short fiction told from the perspective of—and in the empathetic spirit of—Clive Barker’s misunderstood creations. While entertaining on its own merits, as any anthology containing original stories from Seanan McGuire, Nancy Holder and David J. Schow would naturally be, Midian Unmade is best appreciated by Barker fans.

So where can one begin an education in all things Barker? By going back to the beginning, of course.

Books of Blood Volumes One to Six are essential genre reading. Presented within the framework of a paranormal detective investigating the haunting of a house, the dead speak through scratched letters on the skin of a phony medium a collection of stories so widely well-received and reprinted, you might have watched an adaptation of Barker’s early work already. Especially if your 80s and 90s horror game is strong.

Vampires, ghosts, demons of varying levels of capriciousness, monster children, and corrupted souls parade through tales notable not just for their lurid violence but also for their rich prose and touching empathy for outsiders. With thirty mostly excellent stories to choose from, picking the best is difficult. The first “official” short story is one of the most memorable—at least to an admittedly biased New Yorker. “The Midnight Meat Train” takes place in the Bad Old Days of NYC, seen through the eyes of a recent transplant:

“He had seen her wake in the morning like a slut, and pick murdered men from between her teeth, and suicides from the tangles of her hair. He had seen her late at night, her dirty back streets shamelessly courting depravity. He had watched her in the hot afternoon, sluggish and ugly, indifferent to the atrocities that were being committed every hour in her throttled passages.”

But the worst blasphemy resides in the bowels of the earth at the end of a journey that is one of New Yorkers’ worst fears: falling asleep and missing your subway stop late at night.

While “The Midnight Meat Train” is a very specific kind of fear, “Dread” concerns itself with a most universal emotion. Two students obsessed with fear conduct twisted experiments on classmates to provoke a primal response to a compelling and inevitable conclusion. “Jacqueline Ess: Her Will and Testament” is a poignant story of a suicidal housewife suddenly “gifted” with the ability to change people’s body shapes with her mind. Soon to be a film starring Game of Thrones‘ Lena Headey, it’s the latest in a long line of Books of Blood film/TV adaptations seen in Rawhead Rex, Tales from the Darkside, Quicksilver Highway, The Midnight Meat Train, Candyman, and Lord of Illusions.

But if there are any stories from Books of Blood that are absolute must-reads, they are “Human Remains” and “In the Hills, The Cities.” Nowhere in Barker’s fiction are his themes of alienation and awe more on display, nor his word-craft as tight. I can imagine how starved so many readers were for something beyond the suburban, heterosexual spookiness in a pop fiction world reigned over by Dean Koontz and Stephen King before they discovered Clive Barker. This isn’t a knock against King, who was a vocal advocate for Barker’s career, but King has his niche and Barker has his, which is more frankly erotic, urban, and underrepresented. If you’ve ever felt that your own emotions and insecurities were a thousand times more frightening than any demon-possessed car or pissed-off clown, “Human Remains” will get under your skin and stay there. In this mournful take on vampires, a doppelgänger may or may not be more alive than the rentboy he feeds off of.

“In the Hills, The Cities” closes out Volume One of Books of Blood and honestly, for me, the subsequent stories never reached its literal heights, its impossibly grand scope. What starts out like so many cautionary tales—two lovers quarreling on vacation in a foreign country—spirals up and out as they stand witness a ritual so bizarre, so incomprehensible, so loaded with personal meaning and political allegory, it’s impossible not to be swept up in its wake and left speechless after the final line. Truly, it is a perfect example of a perfect fiction. If you read nothing else of Barker, read this.

“Cheeks of bodies; cavernous eye-sockets in which heads stared, five bound together for each eyeball; a broad, flat nose and a mouth that opened and closed, as the muscles of the jaw bunched and hollowed rhythmically. And from that mouth, lined with teeth of bald children, the voice of the giant, now only a weak copy of its former powers, spoke a single note of idiot music.

Popolac walked and Popolac sang.”

It’d be criminal, of course, to maintain that Barker’s subsequent books were less revelatory than his impressive debut.

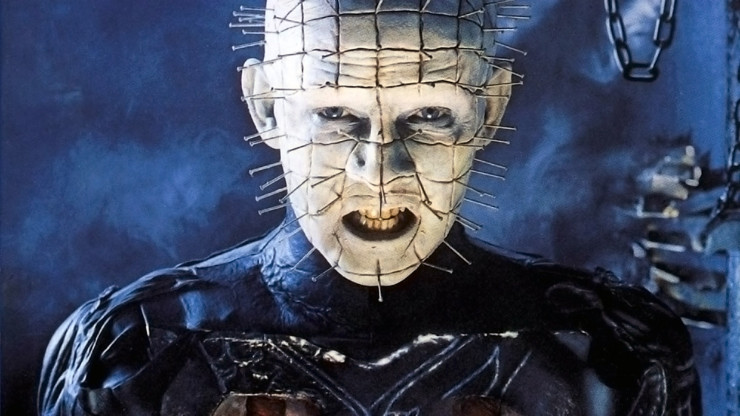

1986’s The Hellbound Heart was the catalyst for Barker’s first big-time foray into another medium he’d go on to dominate. Jaded adventurer Frank Cotton has tried losing himself in every drug, every orifice, every evil offered to him. But he at last meets his earthly release in a sinister puzzle box, the key to a dimension of sadomasochistic tortures ministered by a scarred and pierced Hell priest in leather robes. While I was not enamored with the recent sequel, The Scarlet Gospels, I would without hesitation recommend the graphic body horror, kink, and existential dread of The Hellbound Heart and Hellraiser. Few celluloid baddies are as iconic—nor as poetic—as Pinhead, played with refined cruelty by Douglas Bradley. The franchise continued without Barker at the helm, but you’d be advised to ignore all of the movies after the third installment. There’s some suffering too awful to bear.

Barker’s next feature film was 1990’s Nightbreed. Horribly mangled and badly marketed by the studio, the horror fantasy has been re-released in a director’s cut at last. While I haven’t found the film to age nearly as well as Hellraiser, Nightbreed still remains essential Barker viewing for its menagerie of imaginative creature and makeup designs and a particularly chilling performance from horror director David Cronenberg. I guess it’s not enough that the Canadian auteur has to give us nightmares in his own movies, but casting him as the creepy Dr. Decker was extra cruel. And inspired.

1995’s Lord of Illusions showcases a stylistic leap for Barker as a director and a storyteller. It’s a dark and slick film noir that meshes Hollywood glamour with black magic. It’s the first film appearance of Detective Harry D’Amour, a world-weary detective that Barker has revisited in novels The Great and Secret Show, Everville, and The Scarlet Gospels. Standout scenes include magician Philip Swann’s thrilling final illusion and standout performances from Scott Bakula as D’Amour and recently deceased actor Daniel von Bargen as cult leader Nix, who has risen from his grave to “murder the world.” The movie was also sampled copiously in Canadian industrial band Frontline Assembly’s club hit “Colombian Necktie.” (I think Barker would approve of this factoid.)

Lord of Illusions remains Barker’s last completed film. But the author has been busily writing in different genres and mediums, including Clive Barker’s Undying, a gorgeous PC game notorious for its awful gameplay mechanics.

The Thief of Always is a wonderfully creepy middle grade book perfect for fans of Neil Gaiman’s Coraline. 10-year-old Harvey Swick is swept off to the wondrous Holiday House of Mr. Hood and his creepy servants. When Harvey learns that Mr. Hood’s magic comes with a terrible price, he must save himself and his friends. The book is also illustrated with ink drawings done by Barker himself. It’s unbelievable that this hasn’t been made into a movie yet, though whispers of it swirl up from Hollywood every few years.

Barker has a multitude of fantastical worlds in his brain and a number of his novels deal over and over again with the theme of these better, more colorful, more dangerous, more madcap and seductive dimensions pressing up against or existing parallel to our own. Does one start with the World Fantasy Award nominee Weaveworld, the fan favorite The Great and Secret Show, or, my pick, Imajica?

When the author claims it as his favorite, too, it’s hard to say it’s not essential.

This doorstopper-length fantasy is epic in the truest sense of the word. Earth is the isolated Fifth Dominion, one of five connected worlds overseen by God and whose secrets are unlocked by Maestros—including Jesus Christ—who sometimes work to reconcile Earth with its sister Dominions. Or not. It’s also the story of Pie Oh’Pah, shapeshifting, genderfluid assassin and Pie’s beyond-complicated relationship with a man named Gentle. Barker says that working on Imajica became an obsession. It reads like a hallucinatory meditation on God, faith, metaphysics, love, sexuality, gender, equality, terrible beauty and gorgeous violence. And it’s a standalone!

But if you like your fantasy series combined with torturous waiting for the next novel, Abarat has you covered. It’s the author’s most-current obsession—that return to Hell notwithstanding—and it has the distinction of featuring Barker’s lurid, nightmarish and lovely artwork. Barker has become a prolific illustrator and (very NSFW) photographer as his film and novel output has unfortunately lessened over the years. A splendid collection of Barker’s paintings can be found from the excellent fine art curators at Century Guild.

While Barker himself has largely retreated from public appearances due to poor health, he stands poised to return to fiction and film more regularly with promised next books in the Abarat world and a reboot of Hellraiser. Barker’s influence can be seen most explicitly in the early-90s era of new dark fantasy and horror authors, which included Poppy Z. Brite, Caitlin R. Kiernan, and Neil Gaiman. But his legacy is most clearly felt in all fiction that isn’t content to define evil in stark contrast to good, instead letting the mysteries of darkness speak for itself, no matter how uncomfortable on unfathomable those shifting boundaries can be to mere mortals.

Theresa DeLucci is a regular contributor to Tor.com, covering book reviews, gaming news and TV, including Game of Thrones. She’s also discussed entertainment for Boing Boing. A student of the 2008 Clarion West Writers’ workshop, her short fiction has appeared in ChiZine. Follow her on Twitter.