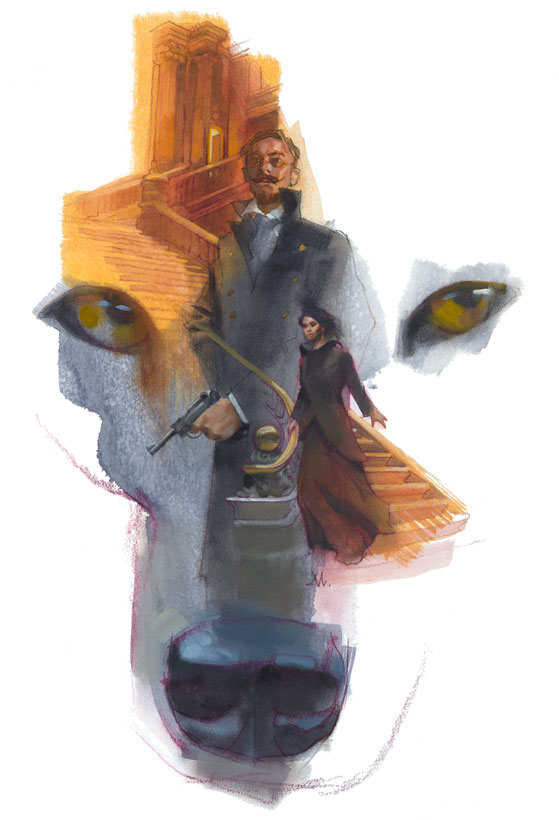

A locked room, a murder, and an unexpected kind of magic: the fifth of Michael Swanwick’s “Mongolian Wizard” tales.

The salamander was the centerpiece of the party. It had been brought from the Marquis de la Fontaine’s menagerie with who-knew-what difficulty (but that, of course, was what servants were for) and contained at the center of a roaring fire in a walk-in stone fireplace of the sort that Ritter remembered fondly from his childhood. On those rare evenings when his parents weren’t entertaining and didn’t feel the need for display, they would sometimes dismiss all the cooks but one and have him prepare something simple enough to be heaped up on a single plate that he, Mother, Father, and his sister would carry inside the massive structure and, seated upon simple wooden stools, eat sitting around a fire such as might have been built upon a barren mountainside a million years ago.

Mercurial by nature, the salamander flickered from shape to shape, as uncertain of form as flame itself—of which she was, natural philosophers agreed, largely composed. Protean though she might be, the salamander’s favored appearance was humanoid. Her hair lashed like pennants in a gale and her arms whipped and snapped among glimpses of thighs, hindquarters, and breasts tipped with hot white sparks, too quickly to be firmly grasped by the eye and thus, as the salamander twisted and writhed, doubly compelling. According to the Marquis, she had been captured by Westphalian miners who had driven a shaft into a vein of fire, and subsequently shipped to his chateau in what was now Unoccupied France just before the onset of the war.

Contemplating the creature, Ritter was almost able to ignore the thunderstorm outside. Each side was employing weather wizards to assail the other with torrential rain and bolts of lightning along an unsteady front that encompassed both forces. It was, in his opinion, an act of damn-foolery that achieved the objectives of each—degrading the opponent’s readiness and morale—to the net benefit of neither. Not that anybody sought out his opinion on such matters.

“I see I have lost you to a rival,” the Marquis’s daughter, Lady Angélique, said, laughing. “You are mesmerized by our fire-maiden.”

“I could hardly deny that I am,” Ritter said, turning away from the creature. “Yet, at your word, I can nevertheless turn my back on her. Were you clad in as wanton a lack of clothing as she, I can assure you I would be unable to tear my eyes away.” In order to avoid giving offense, he carefully modulated his voice to indicate that this was a happy state he dared not seriously aspire to.

Angélique de La Fontaine blushed and lowered her eyes. Then she reached out and instead of giving his hand a sharp admonitory rap, as he had expected, briefly squeezed his forearm. “You are so wicked.”

Ritter’s spirits soared, and he mentally readjusted his chances upward from imaginary to extremely unlikely. This was the sort of society he had been brought up in, where sorcerous talents were common and the company polite. Here, flirtation was no trivial entertainment. Among men of his class, it was understood that passionate, self-assured young women made confident and competent spouses who would put up with no nonsense from the servants and could be relied upon in a pinch to successfully run their husband’s affairs for a few years while he was off at war. The pursuit of a wife was the one of the most serious occupations a man could employ, and it was proof of the existence of an involved and loving Deity that it was so enjoyable as well.

Unpracticed though his social skills were since the Mongolian Wizard had invaded Europe, Ritter knew better than to press his advantage. Only an oaf would do so—and no woman worth having would respond to his loutish overtures. Flirtation alternated advance with retreat, surging forward and back like the ocean tides in an elaborate dance of intention, always looking forward to that instant when those dance steps became virtually indistinguishable from the act of love. “I must say that delighted though I was to receive your father’s invitation, I am astonished that he is holding an entertainment on what may well be the eve of battle.”

“My father and I have complete confidence in our commander. As would you, had you ever encountered him.”

“It is true I have not met Maréchal de camp Martel. But how can you be sure I would be favorably impressed?”

“It is something of a secret,” Lady Angélique said. “But I suppose you are of sufficient rank to be trusted with it. The Field Marshal is a wizard, as so many of our class are, and he possesses a unique talent—that of inspiring loyalty in others. There is not a man in his forces who would not follow him into Hell, confident that he would lead them out again. Provided only that one picks one’s battles carefully, it is very hard to lose with such an army.”

A thunderclap struck just outside the chateau and, reflexively, Ritter cursed. Appalled at himself, he said, “Pray forgive me! I have been on bivouac too long, surrounded by mud and men who think the height of humor is——” He broke off before he could make matters worse.

“I know what such men are like, Kapitänleutnant. During the day, I volunteer in the Tents of Healing.”

“You are a nurse?”

“I am a surgeon.” Lady Angélique’s smile turned flinty. “It runs in my family.”

“I should have guessed,” Ritter said, flushing with embarrassment. Mentally, he estimated what the equivalent military rank for Lady Angélique’s position would be and adjusted his chances downward again. His family was as good as hers. But an officer in the Werewolf Corps was essentially a scout—and thus scarcely of the same prestige as a woman who could reach with her mind into a broken body to repair internal ruptures, encourage cellular growth, and pull a soldier back from the precipice of death. “There is a residuum of sorcerous power about you and it and it is focused in your hands. That strongly implies one of the constructive talents. You are of the peerage and hence a patriot, which means you will do what you can for your country. You——”

“Sir! Sir!” A soldier shouldered his way through the partiers, headed straight for Ritter.

With annoyance he was barely able to conceal, Ritter returned the soldier’s salute and said, ‘Well?”

“Sir Toby’s compliments, sir.” The soldier handed him an envelope.

Scowling, Ritter read the enclosed letter:

Ritter:

I invite you to enjoy a few hands of faro with Field Marshal Pierre-Louis Martel, our learned friend the doctor, and myself. Nothing urgent, I assure you. You must not consider this invitation in any way an order.

T. Gracchus Willoughby-Quirke

He thrust the letter into a jacket pocket. It was, of course, in code, though a simplistic one. Faro, or indeed a reference to a card game of any sort, meant an investigation. The learned doctor indicated an act of violence resulting in serious injury or death, presumably involving Maréchal de camp Martel. The last two sentences were meant to be read as their direct opposites. Acting on an impulse (but Ritter was learning to trust such impulses), he turned to Lady Angélique and said, “I know this is presumptive. But I am called away for an investigation where your skills might well prove useful.”

Lady Angélique’s face grew instantly serious. “Let me change into a riding skirt,” she said. “Tell the ostler to saddle the bay mare for me, and I won’t hold you up for even a minute.”

Without further word, they strode away in opposite directions, creating swirls and eddies of gossip and speculation in their wakes.

The trees were thrashing and the rain was hard as pebbles when Ritter and Lady Angélique arrived at a gallop at the manor house that had been requisitioned for field headquarters. They pulled up by the front entrance and dismounted, their roquelaures glistening in the torchlight of the servants who came hurrying up to take their horses. A guard ran into the house to announce their arrival.

Sir Toby met them in the vestibule. “Terrible news, Ritter,” he said. “I——” Then, seeing Lady Angélique, he asked, “Who is this?”

When Ritter had quickly explained, Sir Toby bent low over the lady’s hand. “Enchanté, mademoiselle. I apologize for my impulsive young subordinate dragging you out here on such a night. But who knows? Perhaps for once in his life, he has made the correct decision. I dared not send for a coroner, but since you are here, you can take the place of one.”

“I will do my best, sir,” Lady Angélique said. “You imply that there has been a death. May I ask whose?”

Her face turned pale when Sir Toby replied, “Field Marshal Pierre-Louis Martel has been assassinated. His body is upstairs.“

At they ascended the grand staircase, Sir Toby said, “This investigation will be entirely in your hands, Ritter. The marshal’s staff is meeting downstairs to determine how to handle tomorrow’s battle, and whether they know it or not, they desperately require my input. Here is all you need to know: The body was discovered little more than an hour ago in Marshal Martel’s room. These stairs provide the only access to the second floor. When the manor house was taken over, all other stairways were dismantled and boarded up. Guards on the ground floor testify that in the time between when Martel last ascended those stairs and the discovery of the body, only his aide and his valet went up after him and nobody came down. Therefore, the murder was committed by one of three people: his valet, his mistress, or his aide.” At the landing, a small, nattily dressed man awaited him. “This is Tomas, the valet. I leave you in his able care.”

So concluding, Sir Toby turned and wallowed down the stairs again, in such a hurry that twice he missed the railing when he grabbed for it, and almost fell.

When he was gone, Ritter said, “Tell us what happened.”

“There is little to tell. Early this evening, the maréchal de camp sent Kasimov and myself away for a few hours. This was a common practice of his whenever he wished to spend time alone with his mistress. We went our separate ways, then reunited on the ground floor at the scheduled time. I went directly to my room while Kasimov proceeded to the master’s door and knocked. When there was no response, he went inside and—”

“He went into the marshal’s room without invitation?”

“That was how the master insisted it be done. Had he wanted privacy, he would have cursed at his aide through the door.”

“Go on.”

“I had barely entered my room when I heard Kasimov shouting for me. This was unprecedented. I ran to his side and saw the maréchal—dead. I confess my shock was so great I did not know what to do. But Dmitri Nikitovich cried, “Mademoiselle de Rais!” and ran to her room, flinging open the door. I hastily flung a sheet over the body for modesty’s sake and followed after him. The mademoiselle was in her room, clad only in a dressing gown, her face white and eyes staring. She sat in a chair, rocking back and forth, as if she had been traumatized. We could get no sensible response from her. So, we went downstairs and reported what had happened. There was a great deal of running around and being ordered about for a time. The mademoiselle was given a sedative and all three of us were told to keep to our rooms. Now, well, here we are.”

“I see,” Ritter said. “Let us begin by examining the corpse.”

Tomas bowed slightly. “The maréchal de camp’s room is this way.” He led them down the hall and into a bedroom. There, lying face-up on the bed with a sheet thrown over him, was a naked man—puffed, reddened, and blistered as if he’d been broiled. The bed linens, however, were not in the least charred. Whatever had killed the marshal had not touched them.

“Dear Lord!” Lady Angélique exclaimed. “I have never seen anything like it!”

“I have,” Ritter said quietly. He looked up at the ceiling, expecting to see a black oval of soot, mirroring that on the bed. Yet there was none. The flames, then, were largely internal rather than external, which ruled out spontaneous combustion. Nevertheless, he said, “Tell me, Tomas, did your master receive any packages or presents recently? New clothes? A dressing gown, perhaps.”

“The master was not the sort of man people give gifts to.”

“And you are absolutely sure this is the marshal’s body?”

“The master is, as you can see, an uncommonly large man. And on the middle finger of his right hand, he wears his ancestral signet ring, an item he valued greatly and which I have never seen him without. Also . . .” The valet shrugged. “Even in this condition, his face is unmistakable.”

Lady Angélique, meanwhile, had stripped off the sheet and was bent low over the corpse. Her hands floated just above the body, forming triangles, squares, and the like, a series of gestures that Ritter understood were mnemonics for focusing her thoughts on the internal organs within. Doubtless by now, experienced as she was, they were as unnecessary as they were habitual.

“The body has been blasted twice,” Lady Angélique said without looking up. “First internally and then externally. His organs are cooked. The first blast would have killed him instantly. The second suggests that anger was involved.”

“Could he have been killed by a salamander?”

“No. A salamander would have left nothing of the house but burning coals.” She straightened. “This is the work of a pyromancer, a fire wizard.”

Ritter turned to the valet. “Who here is a fire wizard?”

“That we know of? No one.”

“Give me a hand turning over the body,” Lady Angélique commanded.

With all three working together (Tomas grimaced with distaste but uttered no complaint), the chore was soon done. There ensued a long silence.

“Mutilation atop murder,” Ritter said quietly. “This is the strangest assassination I have ever seen in my life.” Then, as Lady Angélique delicately draped the sheet she had earlier removed over the violated portion of the corpse, he addressed Tomas. “You may return to your room. We shall begin by interviewing the man’s mistress.”

Mademoiselle Jeanne de Rais raised a stricken and tear-stained face when Ritter entered her room. She was far younger than he had expected—no more than fourteen, by his best guess. Nevertheless, Ritter bowed and said, “My condolences on your loss, mademoiselle.”

The girl nodded silently and looked down at her lap.

Gently, Lady Angélique said, “I am a doctor, dear. If you will permit me to lay my hands on your forehead, I can ease some of your suffering. You will still be unhappy, understand. But the extremes of horror and of despair that I can see you are experiencing will be reduced to manageable levels. Do you give me permission to do so?”

Again, the girl nodded.

Standing behind Mademoiselle de Rais, Lady Angélique touched her fingertips to the girl’s brow, and the tip of each thumb to the sides of her head just below the ears. For several long minutes, neither of them moved. Then the mademoiselle shuddered and the older woman withdrew her hands.

“Is that better, dear?” Lady Angélique asked.

“Yes,” Mademoiselle de Rais said in a small voice. “Thank you.”

“I am glad to be of service. Now, I am fear this man is going to have to ask you some questions. But he will be careful not to alarm you.” This last was said with a warning glare.

“Of course. Mademoiselle, may I ask how long you have been with Maréchal de camp Martel?”

“Almost two years. He was a guest at my father’s estate and he . . . he noticed me. My parents did not want to let me go with him, but the maréchal can be very persuasive. I did not want to go, either. But I said yes.”

“Because of his talent?”

“I imagine so. Sometimes, I am very homesick. But I never leave, though I wish I could.”

“You will be restored to your family very soon, I promise you,” Ritter said. “What can you tell me of this evening’s events?”

“I . . .” Mademoiselle de Rais shook her head. “I remember nothing. I’m sorry.”

“What was the last thing you do remember?”

“I remember lunch. There was a strawberry sorbet. That was nice.”

The young woman looked so childish when she said that that Ritter almost couldn’t bring himself to go on. But he knew his duty, so he said, “I am afraid, mademoiselle, that I must now ask you certain questions about the marshal’s sexual practices. Did he—”

The terrified look on the girl’s face stopped him in mid-question.

“Oh, you idiot!” Lady Angélique exclaimed. She put both hands on Ritter’s chest and pushed him backward out of the room and into the hall. “You have all the tact of a water buffalo. Go interview someone else. I will speak with Mademoiselle Jeanne—alone.”

She slammed the door in his face.

There were four doors in this hallway: Marshal Martel’s at the end, Mademoiselle de Rais’s across from his, the valet’s nearest the staircase, and one more that could only be the aide-de-camp’s room. A young man with a round, heavy, almost ursine face answered the door. He wore a French uniform with a gold aiguillette on the right shoulder.

“You are Capitaine Dmitri Nikitovich Kasimov?”

“Yes.” Kasimov gestured toward a lone green leather chair. He himself sat on the edge of his bed. “You must be the investigator. I will answer all your questions to the best of my ability, Lieutenant—”

“Kapitänleutnant Franz-Karl Ritter.” He took the offered seat, the cigar, and the light from a struck match that Kasimov offered him. “Of the Werewolf Corps.”

“Ah. Then you are a stateless man like myself. You will understand me, then, when I say that having been driven from Russia by the Mongolian Wizard, I would never do anything to weaken the forces opposing him.”

“You think I suspect you of murdering Martel?”

“In your position, I would. I was alone when I discovered the corpse. You have only my word that I did not create it. Further, it will not take you much questioning to discover that I hated the maréchal de camp. I had a military career that I found quite satisfying when he discovered that I had a trick memory for data and made me into his scribbler. So, I had motive and opportunity both.” He lit up a cigar of his own. “But I am doing your job for you. Please, proceed.”

“What is your specialty, captain?” Ritter asked.

“Explosives and demolitions. So, now you have means as well.” Kasimov twisted his mouth into a grin. It struck Ritter that under other circumstances, he would be jolly company. “Only you will find no such materials here, search though you assuredly will. It has been over a year since I had my hands on so much as a fuse.”

“You are obviously a very capable man. Perhaps you have a talent, too?”

“No.”

At that moment, there was a great clamor in the entry hall downstairs and voices bellowed Ritter’s name. “Excuse me,” he said, and leaving his cigar in the Limoges saucer that served as an ashtray, went to the top of the stairs. Down below, he saw four men setting down a cage whose contents obviously alarmed them. The guards at the bottom of the stairs waved them away and, on seeing what had been brought, stepped back from it.

His wolf had arrived at last.

Freki bounded up the stairs to Ritter’s arms and, once he had determined that there was no treat waiting for him in his master’s hands, permitted himself to scratched behind the ears. Only then did Ritter ease his thoughts into the animal’s mind and walk him through the scene of the crime.

He returned to Kasimov’s room then, picked up his cigar, and puffed it back to life again. Freki, who did not like tobacco smoke but was used to it, investigated the room, sniffing at the dresser, under the bed, at the closet.

“You had a drink or two while you were out,” Ritter observed, “and visited a brothel as well.”

“I was a caricature of a soldier with a few hours to kill,” Kasimov admitted. “I am surprised I did not also gamble and get into a drunken brawl. Please tell that beast that there is nothing to be learned by sniffing my boots.”

“On the contrary, there is a great deal to be learned. The fact, for example, that there is no trace of explosives associated with you or the crime scene.”

“As I told you. But I am glad you have eliminated that chain of thought so quickly. Much good it will do me; even though I am innocent and you appear to be an honest man, and therefore I will live, the association with the murder will follow me for the rest of my life. My career is over.”

Ignoring the man’s sudden bout of self-pity, Ritter said, “Tell me, Kasimov. What do you think of Mademoiselle de Rais?”

“Poor child. I have a sister not much younger, and it has not been easy to watch how the maréchal brutalized her. But, again, I hate the man who brutalized my nation more.”

“And Tomas, the valet?”

“A nonentity. He blacks boots, steams coats, gossips with the other servants, steals a plate of cold meats from the kitchen at night. Every man is a mask, I am firmly convinced, and you never know whether there is a demon or an angel lurking within. Save for Tomas. Cut him open and you will find a slightly smaller valet. Cut that one open and you’ll find another valet, and another, and another, all the way down to nothing.”

“Thank you.” Ritter stubbed out the cigar on the Limoges saucer. “You will wait here in your room in case I have further questions for you.”

Kasimov smiled sourly. “I have nowhere else to go.”

Tomas looked surprised by Freki’s presence but graciously welcomed Ritter into his room nonetheless. Ritter was not surprised to see two matching armchairs and assorted furniture far superior to what was in the aide-de-camp’s room. The valet was clearly the enterprising sort of servant who took care to feather his own nest wherever he might find himself.

“You were reading,” Ritter observed, glancing at a book that had been placed, face down and open on an end table. “May I ask what?”

“Ovid. Oh, not his serious poems. The Metamorphoses. It’s trash, really. But trash by a great poet, and thus, the master would allow it within his orbit.”

“Martel was a demanding man, then?” Ritter asked.

“Repugnant is the mot juste, I believe. I see I shock you. But, as you must know, no man is a hero to his valet. Nor, if the man in question is the master, by anyone who knew him. Your dog seems very curious about my possessions.”

“He is a wolf. Tell me about your feelings toward the maréchal.”

“I adored him, of course. I had no choice. But I could see his flaws. Consider: My master’s talent expressed itself almost from birth. The world doted on him. When he was a toddler, other infants shared their toys with him. He did not get in schoolyard fights, because his fellow students deferred to him. As soon as he became interested, girls were eager to assuage his lust. Inevitably, the poor child became a monster of ego. He hardly had a choice.”

“Yet he grew up to become a great general.”

“A great leader—there is a difference. His knowledge of tactics and strategy is rudimentary at best. But that weakness is made up for by his staff. Who, because of their intense loyalty toward him, vie with each other to offer up the best strategies and most cunning tactics for him to present as his own.”

“Tell me,” Ritter said, “about his aide-de-camp, Kasimov.”

“He is a Russian; that says it all. Always moping around about how he lost Russia, he lost his career, he lost his faith, he lost his family, and God knows what else. If he had a balalaika, he’d be playing it right now. Something mournful, no doubt.”

“And the marshal’s mistress?”

“His strumpet, you mean. I’ve shocked you again. But you didn’t have to clean up after them. Trust me, she performed acts no decent woman would.”

His work done, Freki padded softly back to Ritter and lay down at his feet. Ritter, in turn, withdrew his mind from the wolf.

“Speaking of deviant practices,” Ritter said, “I note that you are a sodomite. Please don’t try to deny it. Freki can smell the lubricant that so many of you keep handy and the lilac water that you wear on those occasions when you go looking for companionship in certain dark places frequented by men who are afraid to say aloud what they desire and require such signs to recognize each other.”

“Please, don’t . . .”

“I am not shocked, Monsieur Tomas. There are far more of your kind than most people think—I believe even you would be surprised how many more. It would accomplish nothing to arrest you for your personal proclivities. But given the location of your master’s most grievous injury, one must naturally wonder if sodomy was involved.”

“Whether it was involved or not, I certainly was not,” the valet said with heat. “Of all three of those involved, I am the only one who could not have committed the crime, for I was never alone with him during the time in question. In fact, I—”

Freki’s ears perked and Ritter held up a hand for silence. There were footsteps in the hall. “Ah. Lady Angélique is done with the mademoiselle. You will excuse me, for I must confer with her.”

As each of the rooms on the hall had an occupant, either living or dead, Ritter and Lady Angélique consulted quietly at the top of the grand staircase.

“Mademoiselle de Rais is sleeping quietly now,” Lady Angélique said, “and I have solved your crime for you. The girl and I had a long talk, and it is a sad and sordid tale indeed. Martel behaved monstrously toward the child, routinely forcing her to perform sex acts that she necessarily found repugnant. He was particularly fond of the Greek vice, with himself on top, of course. Do you take my meaning? I can be more specific, if you require.”

“That will not be necessary,” Ritter said uncomfortably.

“We need not dwell upon the girl’s humiliation and anger. The scene is all too easily imagined. Mademoiselle de Rais did not know she was a pyromancer—some talents manifest themselves later in life than others—until the moment when her childish rage summoned up her power and focused it upon her persecutor in two bursts. First, she roasted him alive. Then she did a violence to his body that echoed the violation done her own. After which, she rolled the body over on its back—out of schoolgirl fastidiousness, no doubt—and retired to her room and halfway to hysteria.”

“Well,” Ritter said. “You’ve certainly—”

At that moment, voices filled the air as military men emerged from the basement conference room into the first floor. Among them was Sir Toby, who, seeing them, started up the stairway.

“We attack in the morning,” Sir Toby said. “I have, among my men, a shape-changer who can assume the field marshal’s appearance. The military plans are good, and so long as nobody knows their leader is an imposter—and I am sure we can successfully keep everyone not in on the secret at arm’s length—our forces will behave with the expected loyalty, and the enemies will know they have little chance. . . . Oh, and that reminds me. You did solve the murder, I hope?”

“I did,” Ritter said. “Or, rather, Lady Angélique did. It was a crime of passion.” He explained all. “The young woman is of a good house, so I suspect that if she is sent to a convent, her involvement in the matter can be hushed up.”

“Her godfather is the Duc d’Ys,” Lady Angélique said. “Trust me, she will be healed, not punished.”

“I am glad to hear that,” Sir Toby said. “There is more than enough cruelty in the world as it is.” Then, rubbing his hands, he continued.“Well, we have put in a good night’s work, one and all. I will be busy all night, but the two of you can be spared for few hours. I suggest you get some sleep. Tomorrow will be a long day.”

“No,” Ritter said. “There is one more thing to be done.”

He went to the aide-de-camp’s door and rapped briskly. “Come join us,” he told Kasimov. “We will have work for you in a bit.”

Then he knocked on the valet’s door. Tomas emerged.

“The investigation is complete,” Ritter said.

“You know who killed the master?”

“The matter has been resolved, and that is all you need to know.”

Tomas nodded thoughtfully. “It sounds like the rain has stopped,” he said then. “I think I will take a walk outside to clear my head.”

“No,” Ritter said. “You will not.”

“Eh?” Sir Toby cocked an eyebrow.

“Tell me something, Tomas: Why is it that when I look away from you, I cannot remember the color of your eyes or of your hair, or, indeed, the general cast of your features? Why is it that the sound of your voice flows away from me like water? I am a man who never forgets a face, and yet I swear to you that if you were to step into a crowd, I would be unable to pull you out of it.”

“A good valet is self-effacing, sir.”

“You have taken a virtue and magnified it to the status of a vice. No, you are a spy and a wizard. Your talent is to make yourself unobtrusive. Your purpose is to gather information. And you currently possess a secret that could change the course of tomorrow’s battle. You will not be allowed to leave this house alive.”

Almost too swiftly to be seen, the valet seized Lady Angélique. A knife appeared in one hand, even as the other clutched her throat. A vivid, animal alertness shone in his eyes, a shrewd and calculating cunning, though he must have known that his chances of escaping were slight.

“There is nothing to be gained by this,” Ritter said carefully. “You must let the lady go.” Simultaneously, he slipped his mind back into Freki’s and prepared to launch the wolf at the valet.

But Lady Angélique raised a hand from her throat and moved Tomas’s hand from it, as easily as if it had no volition of its own. Stepping out of Tomas’s embrace, she said, “It is no easy matter to hold a surgeon against her will.” Disdainfully, she shoved the man’s chest with both hands and watched him tumble to the floor. “We know every pressure point in the human body and can compress them at will.”

Sir Toby removed his hand from inside his jacket, without the pistol he carried there. “Lady Angélique,” he said, “again, we are in your debt. Thank you for disabling this villain.”

“Yes,” Ritter said. He turned to the aide-de-camp. “And you will be the hero of the hour, the man who apprehended the assassin and after a fierce struggle—attested to by impeccable witnesses—had no choice but to shoot him.”

Looking grim, Kasimov said, “It will be my pleasure.”

He unbuckled his sidearm.

“Allow me to leave first,” Lady Angélique said. “This is nothing I should see. I did swear a Hippocratic oath, after all.”

“The Night of the Salamander” copyright © 2015 by Michael Swanwick

Art copyright © 2015 by Gregory Manchess