Originally, Walt Disney planned to make a full length feature film featuring Winnie the Pooh but found himself confronting a serious problem: even taken together, the books didn’t create a single story, except—and this is very arguable—the story of Christopher Robin finally growing up, which for the most part is contained in the final chapter of The House on Pooh Corner and hardly qualifies as an overreaching storyline. Character development, again with the exception of Christopher Robin, was also non-existent: the basic point of that final chapter in The House on Pooh Corner is that the One Hundred Acre Forest will always exist, unchanged, and that someplace on that hill, a boy and his bear are still playing.

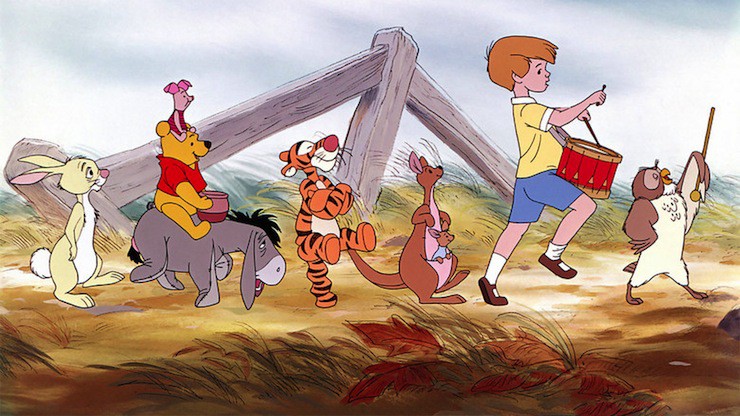

Faced with this, Walt Disney ordered a new approach: a series of cartoon shorts, strongly based on the stories in the original two books. Initially appearing between 1966 and 1974, the cartoon shorts were bundled together with a connecting animation and a short epilogue to form the 1977 feature The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, with Christopher Robin’s voice re-recorded (he was voiced by three different children in the original shorts) to maintain consistency.

(Quick note: Legally, it’s Winnie-the-Pooh if you are referring to the book character, Winnie the Pooh (no hyphens) to the Disney version.)

If you are expecting an unbiased review of this film, reduce your expectations now. I did not see the 1977 release, but two of the shorts were small me’s very very very favorite Disney films ever. Oh, sure, Cinderella had those mice and that beautiful sparkly dress, and Lady and Tramp had cute dogs, and Aristocats had singing cats, and I was firmly escorted out of Bambi thanks to a complete inability on my part to distinguish animated forest fires from real forest fires, but The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh had Tigger. Who bounced and bounced and bounced. I laughed and laughed and laughed. Small me also was blown away by the image of the characters using the text of the book to climb out of various problems, and the image of letters in the book getting blown by the wind and hitting the characters. Those scenes were arguably among the most formative film moments of my childhood, still impacting my approach to writing fiction today.

Also, Tigger.

Because of this, I steadfastly avoided watching the film as a grownup, not wanting my little wondrous childhood memories shattered. And then this Read-Watch came up. I considered. And considered again. And finally pressed the play button on Netflix.

Does it hold up?

Well, almost.

Grown-up me is not quite as entertained by the images of Tigger bouncing on everyone—I’m not at all sure why that made me laugh so hard when I was small, but there we are. Small me had Very Little Taste. Grown-up me had also just read the books, and couldn’t help finding the books just a little better. Child me completely missed just how much of the film contains recycled animation sequences, though to be fair I originally saw the film in separate shorts, where the recycling isn’t quite as obvious. Adult me also can’t help noticing the differences in animation techniques and colors as the movie progresses, which is slightly distracting. Child me was also wrongly convinced that the film had a lot more Eeyore in it (apparently not) leaving grown-up me a little disappointed. And in the intervening years, grown-up me somehow or other got a slightly different voice in her head for Pooh, which was slightly distracting, though the voicing for Piglet and Tigger is spot on.

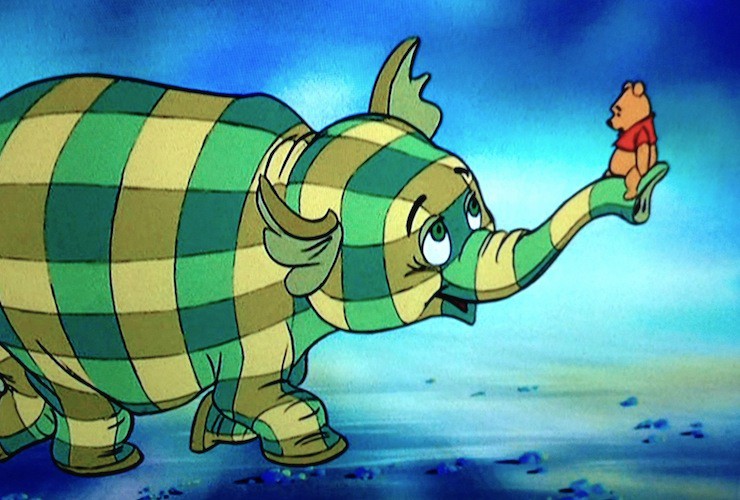

And adult me is just a little sad that the film does not use the silly rhymes Milne wrote for both books, and—especially in the first short—exchanges some of Pooh’s literal dialogue for phrases like “rumbly in his tumbly,” and the rather unbelievable bit of dialogue where Pooh—Pooh—knows that Heffalumps and Woozles are actually Elephants and Weasels. That is just not the sort of thing that Pooh would know. At all. Not that Tigger, the one saying Heffalumps and Woozles, would know either, but let us not give Pooh too much education here.

And also—and I stick to this—the Hundred Acre Wood doesn’t have elephants. Or weasels. It has Heffalumps. And Woozles. And one Tigger.

But—and this may be nostalgia coloring my viewpoint—other than things like this, The Many Adventures of Winnie-the-Pooh does hold up remarkably well.

The film starts off with a glimpse of Christopher Robin’s room, scattered with various toys, including American versions of the various stuffed animals that Christopher Robin plays with, before entering the book. And by this, I don’t just mean the fake gold covered books that Disney had used in opening scenes for its fairytale books, but rather, the U.S. edition of Winnie-the-Pooh—complete with the table of contents, the text and page numbers, if with slightly altered illustrations—a point that would become critical in later court arguments in the state of California.

The lawsuits were still to come. For now, the slightly altered illustrations were just part of an artistic decision to let a little illustration of Christopher Robin that was almost (but not quite) like Ernest Shepherd’s Christopher Robin start moving on the screen, while the text remained steady, before the camera moves over the page to introduce us to the other characters in the film—Eeyore, Kanga, Roo, Owl, Rabbit, Piglet and Pooh—before having Pooh step out of his house and merrily jump across letters that spell out BEARS HOWSE.

It’s a fun animated sequence, and also a nice nod to the original Winnie-the-Pooh, which itself existed in an odd limbo between reality and story, where two of the main characters in the stories were real people—well, a real boy and a real teddy bear—asking to hear stories about their adventures in the woods, and getting upset if they weren’t mentioned in these tales—but who were also fictional characters, raising questions of the relationship between narrative and reality.

The Many Adventures of Winnie-the-Pooh never gets that deep—the closest it ever gets to “deep,” actually, is a hug between Rabbit and Tigger later on in the movie, and I’m seriously stretching the definition of “deep” here. But the animators did play with the relationships between characters and text. Pooh speaks directly to the narrator, complaining that he doesn’t want to go on to the next part of the film—he’s eating honey! Priorities, narrator, priorities! I’m with Pooh on this one. In the blustery day portion of the film, Pooh gets hit by letters from the book. Tigger, stuck in a tree, calls out to the narrator for help, who tells him to move to the text—and then kindly turns the book, just a little, so that Tigger can slide down the letters instead of having to jump down from the tree.

As the film continues, pages turn, letters fly, the narrator kindly reminds us what page numbers we are on, and Gopher—the one character not in the book—reminds us from time to time that he’s not in the book, and when he later mostly disappears from the film, it’s ok, because he’s not in the book. And also because Gopher is not very funny. He’s a replacement for Piglet, who is very funny, but who for whatever reason—stories differ—was left out of the first short. Critics howled, and Piglet was back for Blustery Day and Tigger Too, along with the bouncy Tigger.

The animators also had fun with a dream sequence where Pooh dreams about heffalumps—clearly heffalumps, not elephants, in weird shapes and sizes—and with a great sequence during Blustery Day where Owl’s house is blown down, while Owl and Piglet and Pooh are still in it. Alas, the great bit that followed in the book, where Piglet got a chance to be brave by climbing out of Owl’s mailbox, is gone—but Piglet still gets a great scene later, made even more poignant by the number of characters who know just how brave and selfless Piglet is.

As the film progressed, animators had more and more fun with the text—which also meant they were forced to take more and more dialogue from the text, since viewers could see it up on the screen. That greatly improved the film’s second two sections. I don’t mean to disparage the first short, exactly—especially with the great scene where Rabbit, realizing he’s stuck having Pooh in his door for some time, tries to turn Pooh’s rear end into something at least slightly artistic—but it’s just not as funny as the rest of the film, which stuck closer to the book. The animation, too, looks rough. In some cases, this is all to the good—the rough transfer process to animation cels meant that a lot of rough pencil marks got transferred too, giving Pooh, in the first short, a slightly messier, rougher look that was a little closer to the Ernest Shepard originals. In other scenes, this is a lot less good; the later shorts, created after Disney had more experience with the new xerography technique, look cleaner and brighter.

The rest of the film does, admittedly, take more liberties with the plot (what there is of it), combining the flood story from Winnie-the-Pooh with the blustery day and finding a house for Owl stories in The House at Pooh Corner, for instance. And at no point can I remember the Pooh in the book staring at length at his reflection in the mirror and talking to it, while remaining completely unaware that the Pooh in the mirror is, well, not a completely different bear. (Though, for the record, when you are four years old, this is also really really funny if not quite as funny as Tigger bouncing, so this is an understandable addition.) I can’t remember book Pooh singing, “I am short, fat, and proud of that,” as an excuse to eat more honey. And I rather miss Pooh’s ability—however accidental—to solve certain problems and triumph by finding the North Pole.

But despite these tweaks to dialogue and characters, and changes to the plot, this remains one of Disney’s most faithful literary adaptations—which, granted, may not be saying much, especially after what happened to The Jungle Book. It ends with dialogue taken word for word from The House at Pooh Corner, and with the same wistful hope, and if Milne purists decried the results, I still can’t help regarding it with warmth.

Also, Tigger.

Paul Winchell, the ventriloquist who voiced Tigger, earned a Grammy Award for the Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too! part of the film. He went on from this to voice Gargamel in The Smurfs, which no doubt says something deep about life and Hollywood, but also is no doubt something we don’t want to examine too closely. The second short won an Academy Award for Best Animated Short film, and the bundled film, if not a box office blockbuster, at least earned enough money to pay for the added animation. And although Walt Disney died before the third short was produced, it was the last of the Disney animated classics that could claim Walt Disney’s personal involvement, and along with The Rescuers helped director Wolfgang Reitherman, who had more or less taken over Walt Disney’s supervising animation role, keep his job after the tepid The Aristocats and Robin Hood. It was also one of the first animated films that Don Bluth worked on, giving him training in the art—someone we’ll be discussing a bit more when we come to The Fox and the Hound.

But for Disney, the long term legacy of the film was twofold: money (a lot of it) and lawsuits (a lot of this too).

Disney lost no time marketing merchandise based on the film, which soon outsold products based on (gasp!) Mickey Mouse himself. To this day, even post the introduction of Disney Princesses, Disney Fairies, and Buzz Lightyear, Pooh remains one of Disney’s most valuable assets, featured in toys, clothing, jewelry, and various household items. Pooh also has his Very Own Ride at Disneyland, Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom, and Hong Kong Disneyland (all accompanied, of course, by a store), and several of the characters make regular appearances at the theme parks.

The issue, of course, was who exactly would get the money—as much as $6 billion annually, if estimates from Forbes are correct—from all of this. Not necessarily the Milne estate: A.A. Milne had sold rights for nearly everything except for publication over to Stephen Slesinger, Inc, including, a U.S. court later agreed, rights for toys. Not necessarily Disney, who had—technically—only licensed the film rights, not additional rights—at least according to Stephen Slesinger, Inc. Disney, however, argued that the film rights included the rights to create and sell merchandise based on the film Pooh characters, sometimes calling the book characters created by Milne/Shepard “classic Pooh,” except when creating certain Disney products also called “classic Pooh.” Disney also later licensed additional rights from the Pooh Properties Trust and from Stephen Slesinger’s widow, Shirley Slesinger Lowell. And just to add to the confusion, some of these properties were trademarked, some copyrighted.

Not surprisingly, the confusion over all this, and the genuine difficulty of consistently distinguishing between “Classic Eeyore” and “Disney Eeyore,” led both groups into an extensive and expensive legal fight that lasted for eighteen years, with nasty accusations from both sides: Disney, for instance, was accused of destroying 40 boxes of evidence; in turn, Disney accused the Slesinger investigators of illegally going through Disney’s garbage. A.A. Milne’s granddaughter stepped in, attempting to terminate Slesinger’s U.S. rights to Disney, a lawsuit that—perhaps because it didn’t involve questionable legal or investigative practices—went nowhere despite eight years of additional wrangling.

A 2009 federal court decision granted all copyright and trademark rights to Disney, while also ordering Disney to pay royalties to the Slesingers. That still left Disney in control of most of the revenue from Winnie the Pooh, making the character one of Disney’s most valuable properties. With the exception of Disneyland Paris, every Disney theme park has a Winnie the Pooh attraction and attached store, as will Shanghai Disneyland Park, opening in 2016. An incomplete list of Winnie the Pooh Disney merchandise includes toys, jewelry, clothing, games, cellphone cases, backpacks, fine art, and Christmas tree ornaments. Estimated sales have led Variety to list the Winnie the Pooh franchise as the third most valuable in the world, behind only Disney Princesses and Star Wars—also owned by Disney.

It was an incredible return on what were initially just three cartoon shorts featuring a small bear of Very Little Brain, which, even before that dizzying marketing success, had done well enough to encourage Disney executives to take another look at animation. Sure, The Aristocats and Robin Hood had failed to take the world by storm, and Walt Disney was no longer around to inspire films, but the 1974 short had gained a lot of positive attention, and the studio had this little thing about mice hanging around.

The Rescuers, coming up next.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.