Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

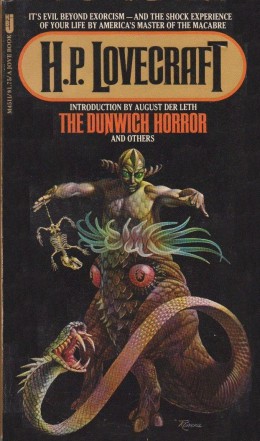

Today we’re looking at the second half of “The Dunwich Horror,” first published in the April 1929 issue of Weird Tales. You can read it here; we’re picking up this week with Part VII.

Spoilers ahead.

“Grandfather kept me saying the Dho formula last night, and I think I saw the inner city at the 2 magnetic poles. I shall go to those poles when the earth is cleared off, if I can’t break through with the Dho-Hna formula when I commit it. They from the air told me at Sabbat that it will be years before I can clear off the earth, and I guess grandfather will be dead then, so I shall have to learn all the angles of the planes and all the formulas between the Yr and the Nhhngr. They from outside will help, but they cannot take body without human blood.”

Summary: Authorities suppress the truth about Wilbur Whateley’s death, while officials sent to sort out his estate find excuses not to enter the boarded-up farmhouse, from which a nameless stench and lapping come. In a shed they find a ledger-diary in unknown characters. They send it to MU for possible translation.

On September 9, 1928, horror breaks loose in Dunwich. After a night of hill rumblings, a hired boy finds enormous footprints in the road, bordering trees and shrubs shoved aside. Another family’s cows are missing or maimed and drained of blood. The Whateley farmhouse is now in ruins. A swath wide as a barn leads from the wreckage to Cold Spring Glen, a deep ravine haunted by whippoorwills.

That night the yet-unseen horror attacks a farm at the edge of the glen, crushing the barn. The remaining cattle are in pieces or beyond saving. The next night brings no attacks, but morning lights a swath of matted vegetation, showing the horror’s route up altar-crowned Sentinel Hill. The third night, a frantic call from the Frye household awakens all Dunwich. No one dares investigate until daybreak, when a party finds the house collapsed and its occupants vanished.

Meanwhile, in Arkham, Dr. Henry Armitage has been struggling to make sense of Whateley’s diary. He concludes that its alphabet was used by forbidden cults as far back as the Saracen wizards—but it’s being used as a cipher for English. On September 2, he breaks the code and reads a passage about Wilbur’s studies under old Wizard Whateley. Wilbur must learn “all the angles of the planes and formulas between the Yr and the Nhhngr” in order for “them from outside” to clear our world of all earth beings.

Armitage reads in a sweat of terror, finally collapsing in nervous exhaustion. When he recovers, he summons Professor Rice and Dr. Morgan. They pore over tomes and diagrams and spells, for Armitage is convinced no material intervention will destroy the entity Wilbur’s left behind. But something must be done, for he’s learned that the Whateleys conspired with Elder Things that want to drag the earth from our cosmos into the plane from which it fell vigintillions of eons ago! Just as Armitage believes he has his magical arsenal in hand, a newspaper article jokes about the monster that bootleg whiskey’s raised in Dunwich.

The trio motor to the cursed village in time to investigate the Frye ruins. State police arrived earlier, but defied locals’ warnings and went into Cold Spring Glen, from which they haven’t returned. Armitage and company stand overnight guard outside the glen, but the horror bides its time. The next day opens with thunderstorms; under cover of the untimely darkness, the horror attacks the Bishop farm, leaving nothing alive.

The MU men rally locals to follow the trail leading from the Bishop ruins toward Sentinel Hill. Armitage produces a telescope and a powder that should reveal the invisible horror. He leaves the instrument with the locals, for only the MU men climb Sentinel Hill to assail the horror. It happens to be Curtis Whateley—of the undecayed Whateleys—who’s using the telescope when the MU men spray-dust the horror into brief visibility. The sight strikes him down, and he can only stammer about a thing bigger than a barn, made all of squirming ropes, with dozens of hogshead-like legs and mouths like stovepipes, all of it jellyish. And that half-face on top!

As the MU men begin chanting, the very sunlight darkens to purple. The hills rumble. Lightning flashes from a cloudless sky. Then sounds begin that no hearer will ever forget, cracked and raucous vocalizations of infrabass timbre. As the spell casters gesticulate furiously, the “voice” waxes frantic. Its alien syllables suddenly lapse into English and a frenzied thunder-croak of “HELP! HELP! ff-ff-ff-FATHER! FATHER! YOG-SOTHOTH!”

A terrific report follows, from sky or earth no one can tell. Lightning strikes the hilltop altar, and a wave of invisible force and choking stench sweeps down to nearly topple the watchers. Dogs howl. Vegetation withers. Whippoorwills fall dead in field and forest.

The MU men return. The thing is gone forever, into the abyss from which its kind come. Curtis Whateley moans that the horror’s half-face had red eyes and crinkly albino hair (like Lavinia’s) and Wizard Whateley’s features, and old Zebulon Whateley recalls the prediction that one day a son of Lavinia’s would call to its father from atop Sentinel Hill. And so it did, Armitage confirms. Both Wilbur and the horror had the outside in them: they were twins, but Wilbur’s brother looked much more like the father than he did.

What’s Cyclopean: Wilbur’s brother. Is this the only time that something living is described as cyclopean? *checks* Sort of. In Kadath, night-gaunts are like a flock of cyclopean bats.

The Degenerate Dutch: Poor rural folk are too scared to handle local monsters, but need to follow along nervously behind the brave scholars who come in to save the day—even watching the day-saving through a telescope may be too much for them. They also speak in eye-searing spelled-out dialect, while Ivy League professors (whom one suspects of having thick Boston accents, if they didn’t force themselves into a different thick accent at Cambridge) get standard English spelling.

Mythos Making: Yog-Sothoth is the gate and Yog-Sothoth is the key to the gate—not the nice gate that lets you learn the secrets of the universe, but the one through which the old ones will come back to clear off the Earth and drag it into another dimension. I guess that’s a secret of the universe, sort of.

Libronomicon: Wilbur Whateley’s ciphered journal proves most distressing. To decrypt it, Dr. Armitage draws on “Trithemius’ Poligraphia, Giambattista Porta’s De Furtivis Literarum Notis, De Vigenère’s Traité des Chiffres, Falconer’s Cryptomenysis Patefacta, Davys’ and Thicknesse’s eighteenth-century treatises, and such fairly modern authorities as Blair, von Marten, and Klüber’s Kryptographik.” A search on Thicknesse’s name turns up a Harry Potter character, and 18th century author Philip Thicknesse who mostly wrote several travelogues and a debunking of the original mechanical Turk, but also A Treatise on the Art of Decyphering and of Writing in Cypher.

Wait a second. That (fairly obscure) information on Thicknesse came from a 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica article. That lists exactly this set of references, in exactly this order. Nice to know that for all his erudition, sometimes Howard just looked up what he needed on Wikipedia, same as the rest of us.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Dr. Armitage has a bit of a nervous breakdown after learning what the Whateleys are about. Who wouldn’t?

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Poor baby Whateley. Locked in the attic for years, crying for his Daddy…

Sure, we’re talking about a house-sized eldritch abomination. But the kid’s just a stupid teenager, raised to believe this is his destiny. There’s a plausible crossover between “Dunwich Horror” and Good Omens out there, is what I’m saying, though it’s probably not what Lovecraft had in mind.

Unless it is, of course. He’s not exactly subtle about his disdain for rural hillfolk, and all but states outright that with enough “decay” and “degeneracy,” breeding with outer gods in an attempt to immanentize the eschaton is simply the inevitable next step. Which implies that nurture, as well as nature, has a strong hand in how the Whateley twins turned out. With a little kindness, and maybe a blood bank on tap, they might have become rather more prosocial members of society.

The cosmology here is some of the scariest stuff in Lovecraft, and some of the best remembered. It’s often conflated with the potentially civilization-threatening upheavals prophesied to come with Cthulhu’s awakening, but the Old Ones don’t trifle around with inspiring riots and alarmingly weird art. They want the entire planet—humans are just vermin that happen to have crawled in while they were away. This trope will show up again and again in every story that owes something to cosmic horror, from Doctor Who to the Laundry Files. And it’ll cause shivers every time. After winter, summer.

Not all of how the story plays out is worthy of these underlying concepts. I’m continually irritated by how the Dunwich natives are handled. Seriously, does anyone think a hoity toity Ivy League professor doesn’t have an accent? And then there’s the assumption that courage and initiative come with literal class—as in “Lurking Fear,” the terrified locals must wait for rescue from elsewhere.

Lovecraft liked “men of action,” and indeed thought the presence of such men a central indication of anglo superiority. (He claimed, in particular, that Jewish men could never show such courage. My response is unprintable in a family blog post.) Armitage is an example of the type who, taken on his own merits, could be pretty cool—the 70-year-old college professor, forced into the field to combat evil. Did he do this often when younger—is this Indy pulled out of retirement for one last high-budget adventure? Or, perhaps more intriguingly, is this the first time he’s actually confronted the reality of Miskatonic’s “folklore” texts, and applied his studies to something more dangerous than a dissertation defense? Either way could make for compelling characterization.

But then we run into Howard’s perennial problem: he was himself the very inverse of a man of action. While we do get occasional stories directly from an actor’s point of view, more often the author pulls back to a second or third-hand observer—someone closer to the author’s own methods of observing the world. Here, that requires unreasonably monolithic insufficiency from everyone who might otherwise defend their own town. The Dunwich observers must turn away or faint every time Lovecraft wants to raise dramatic tension, or ensure revelations are revealed in their proper order. The final revelation is in fact a kicker, but I could have done with some alternative to the gape-jawed locals waiting awestruck to receive it.

Anne’s Commentary

The stakes in this story are terribly high, no less than the eradication of all earth life and the planet’s abduction to parts—planes—unknown. By Elder Things of an elder race. Except probably not the Elder Things in “At the Mountains of Madness,” which seem to be much less potent and malevolent than the Old Ones described in the Necronomicon passage Armitage reads over Wilbur’s shoulder. The Old Ones being, I take it, the Outer Gods. Of whom even Cthulhu is but a lesser cousin, even though he’s a Great Old One. Are we thoroughly confused yet? No problem. How could we mere humans hope to classify the Mythos entities, as if they were so many beetles instead of the Elder Great Old Outer Things/Gods that they are? Our languages are too puny to encompass their dark glory!

Ahem.

As I opined last time, Dr. Armitage is the most effective of Lovecraft’s characters. Though I think I called him “efficacious,” as if he were an object, and really, his characterization doesn’t quite merit that. His predecessor is Dr. Marinus Bicknell Willett, who fails to save Charles Dexter Ward but is nevertheless a quick enough study in dark magic to put down Ward’s nefarious ancestor. At first glance the standard academic type, Armitage is remarkable for his imagination and the credulity to which it and his wide erudition lead him. He scoffs at rumors about Wilbur’s parentage: “Shew them Arthur Machen’s Great God Pan and they’ll think it a common Dunwich scandal!” Machen, hmm. So Armitage is well-read in weird fiction, as well as esoteric tomes. He’s on to Wilbur’s deep “outerness” right away, and he doesn’t try to intellectualize the intuition away. Instead he takes steps to keep Wilbur from all the Necronomicons, not just the one at Miskatonic.

Coming on the dying Wilbur, exposed in all his monstrosity, Armitage might have screamed—it’s uncertain which of the Miskatonic Three vents his shock in that fashion. But he’s one of the few witnesses to Mythos truth who doesn’t then faint and/or flee. That deserves some points in my book. I can also believe, given his scholarly background and access to the Whateley diary, that he could figure out the wizardly way to dismiss Wilbur’s twin.

Old Henry, he’s cool by me. For my own take on the Mythos, I’ve grabbed him to found the Order of Alhazred, which strives to head off Outer/Elder/Great Old threats to our world wherever they may crop up. Because once alerted to the cosmic danger, you don’t think Henry could simply collapse in his armchair with the latest E. F. Benson, do you? Speaking of Benson, Armitage associates the Dunwich horror with “negotium perambulans in tenebris,” a “business (thing, pestilence, distress, etc.) that walks in darkness.” The phrase comes from Psalm 91, but perhaps someone like Armitage would also know it from Benson’s eerie 1922 short, “Negotium Perambulans.”

Back to common Dunwich scandals. I suppose that in their run-of-the-Dunwich-mill murmurings, the villagers assumed Wilbur was the result of incest, old Whateley’s son as well as grandson. Poor Lavinia! It’s a close race between her and Asenath Waite for the dubious honor of most abused woman in Lovecraft. It’s obviously not healthy to be a wizard’s daughter, or wife for that matter given Mrs. Whateley’s mysterious death. There are also the women of Innsmouth, some of whom must have been coerced into “entertaining guests” of the Deep One persuasion. And what about those Jermyns and their maternal ancestors? And that nasty Lilith under Red Hook? And Ephraim Waite posing as Asenath, leerer at girl’s school maidens and ravisher of men? And those necrophiliacs of “The Hound”? Sex is such an icky, dangerous thing! It sounds like the elder Wards had a good marriage, and the Nahum Gardners seemed a happy family until they started to fall apart colorfully. Eliza Tillinghast found Joseph Curwen unexpectedly gracious and thoughtful, but we know his motivation for marrying, which was to continue his line, down to the descendent who would resurrect him should he need resurrecting.

Yes, sex is icky, and sex creates families, which can be such problems. And what’s the ultimate icky sex? It’s got to be sex with Outer Gods, right? Old Whateley assured his cronies that Lavinia had as good a “church wedding” as anyone could hope for. Not much of a honeymoon, though, if Armitage is right in asserting that Yog-Sothoth could only have manifested on Sentinel Hill for a moment. Ew, ew, ew. Or maybe not so much, if you’re into congeries of spheres. Could be kind of bubble-bathy? Definite ew-ew-ew to the obstetrical problem of delivering a baby with the hindquarters of a dinosaur. Delivering a barely material twin, on the other hand, must have been a comparative breeze.

Howard, don’t scowl. You invited such speculation when you mentioned screams that echoed over the hill rumbles on the night Wilbur (and twin) arrived. That one detail was enough.

Cotton Mather, collector of tales of terrible births, would have loved it.

Next week, we continue to explore the Lovecraft-Machen connection in “The Tree.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s non-Hugo-nominated neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. The second in the Redemption’s Heir series, Fathomless, will be published in October 2015. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.