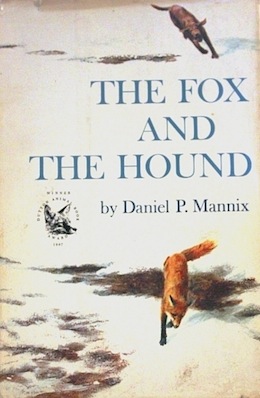

In a long, colorful life, Daniel P. Mannix worked as a sword swallower, a fire eater, a photographer, a filmmaker, a stage magician, a breeder, a collector of exotic animals for zoos, and occasionally (and more disreputably) as a writer. His nonfiction books and articles covered an equally astonishing range of subjects: gladiators, magicians, torture, hunting, travel, the Atlantic slave trade, the early Oz films (he was an avid fan and early member of the International Wizard of Oz club), occultist Aleister Crowley, and the United States Navy.

And he wrote what may be the so far hands down most depressing book of this reread yet—a list which, let me remind you, has so far included such cheery subjects as puppet torture, probable pedophilia, the inevitability of death, puppy killing, rape, and child abandonment. What I’m saying is, The Fox and the Hound had competition, deep competition, and it still won.

Initially, The Fox and the Hound starts out on what seems to be a perfectly cheery note, inside the mind of Copper the hound. This also means inside a world comprised mostly of scents. Copper does not see very well with his eyes, instead navigating the world through his nose, which proves useful when his Master takes him and the other dogs out on a hunt for a bear.

This is the first indication that things in this book might not go all that well. It’s difficult to know who to feel more sympathy for here, the bear or the dogs. It also might be difficult, if you’re me, not to cheer on the bear just a little bit when it correctly finds the real threat—the Master—and sinks his teeth into the Master’s shoulder. A freaked out Copper—it’s a bear—doesn’t attack, but his dog rival, Chief, does, saving the life of the Master like THANKS CHIEF YOU DIDN’T HAVE TO (we’ve had plenty of signs already that the Master is not one of humanity’s bright spots, even leaving aside the bear hunt). This does make Chief the favorite dog. For a bit. Deeply depressing Copper.

The next chapter takes us inside the mind of Tod, a fox rescued by humans as a pup—and before you feel too sympathetic about those humans, this is right after all of his littermates were killed, but moving on. The humans keep Tod as a pet for a few months, which teaches him a bit about them, but soon enough, instincts take over, and he heads back into the wild.

Eventually, he finds himself hunted by Copper, the Master and the Master’s other hounds, including Chief. Tod is clever enough to trick Chief into jumping onto train tracks and getting killed by the train. The Master and Copper then spend the rest of the book trying to kill Tod—the Master, out of vengeance and apparently a general dislike for foxes and some severe personality issues, Copper out of pure love for his human.

In between tense descriptions of fox hunting and things really not going well, Mannix takes time to explore Tod’s world in depth—his own hunting practices, socialization with other foxes, food he particularly likes, the fun he has springing traps set for him and others, how he finds new dens and adjusts to the changes in seasons.

This also includes a fairly graphic description of Tod’s encounter with a vixen, an encounter that includes a fight with two other male foxes and evidence that adult foxes are not very good at providing proper sex education to little male foxes and that instinct is not always a reliable guide with sex, well, fox sex at least, but that does end with this happy thought:

They were well mated; the older, more experienced vixen to the powerful, enthusiastic young male in the full glory of his youthful prowess.

Also, on a fun note, the vixen chooses Tod, not the other way around, and she’s the one to kill her rival vixen.

This encounter naturally results in little fox puppies, who are adorable and cute right up until one of them goes after a domestic chicken, attracting the attention of the dog on that farm. The two adult foxes attack the dog, which in turn leads to the farmer calling the Master and Copper for help. Copper manages to find the fox den; the Master and the farmer kill all of the little fox puppies with methane like I TOLD YOU THIS WAS THE MOST DEPRESSING BOOK YET.

That is, until the fox meets another vixen, and has another litter of puppies, and the Master and Copper find these puppies too, and, well –

AND THAT’S NOT EVEN THE MOST DEPRESSING PART OF THE BOOK.

Seriously. ADORABLE PUPPY DEATHS—twice!—are not the saddest, most depressing part of this book.

Despite this focus on foxes and the deaths of their little fox puppies, and the terrible things that happen to foxes, hounds, and (to a lesser degree) chickens, bears, minks, and songbirds, however, this is really more a book about humans than about animals. The animals, after all, are responding to the humans, and readers are responding to the things the animals notice, but cannot understand: the scent of alcohol around the Master and the resulting displays of fury; the symptoms of rabies; the arrival of the suburbs.

That arrival sets up the major twist of the book: for all that The Fox and the Hound is clearly an anti-hunting novel, arguing that hunting is not just bad for foxes and bears, but also for dogs and humans, the suburbs, not hunting, end up being the real threat to foxes, dogs and humans. Mannix even argues that the foxes—accidentally—actually can help with some farms and agriculture, by removing pests from fruit trees and keeping the rodent population down, when, that is, the foxes aren’t eating chickens. And the foxes mostly thrive when the land is devoted to hunting and farming: this—accidentally—creates great habitat for them, and the land and the forest thickets shelter several healthy, well fed foxes with thick, luxurious pelts who can hunt more than they and their pups can eat.

Once the suburbs arrive, however, all this changes. Readers might not mourn the disappearance of the old world, with its bear hunts and farms and dog killing trains, but the text does. Most of the dogs owned by the Master disappear; the foxes grow mangy and cowardly and skinny and, thanks to garbage cans, lose their ability to hunt (though I’d think the resulting fights with raccoons would keep the foxes in shape, but this isn’t a book about raccoons). Scents from cars and paved roads confuse and terrify the animals. Rabies breaks out through the animal population, worsening human interaction. The final chapters become almost nostalgic for the hunting days, and more of a fierce polemic against the rapid expansion of the suburbs in the 1960s.

It’s an excellent book to give anyone interested in a detailed narrative of the life of a fox, or to how foxes adjust to incoming suburban developments, or in the many many ways foxes can die. I also recommend it to anyone thinking about destroying a wilderness area in order to build bland, cookie cutter houses or strip malls.

But it’s not, to put it mildly, the sort of book you would imagine Disney, or any Hollywood studio, really, choosing to make a children’s movie of. Then again, Disney had previously managed to make popular films out of Pinocchio and Bambi, and had created films that often seemed to resemble the source material in name only with Sleeping Beauty and The Jungle Book. How bad, really, could things get?

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.