“Metamorphosis”

Written by Gene L. Coon

Directed by Ralph Senensky

Season 2, Episode 2

Production episode 60331

Original air date: November 10, 1967

Stardate: 3219.8

Captain’s log. Kirk, Spock, and McCoy are transporting Assistant Federation Commissioner Nancy Hedford via shuttlecraft. In the midst of negotiations on Epsilon Canaris III, she contracted Sakuro’s Disease, a very rare disease that Hedford nonetheless thinks Starfleet should have inoculated her against before going on this mission. Her attempt to bring about peace on that world was interrupted, but Kirk assures her that they’ll get her to the Enterprise in time to fix her up and get her back to work.

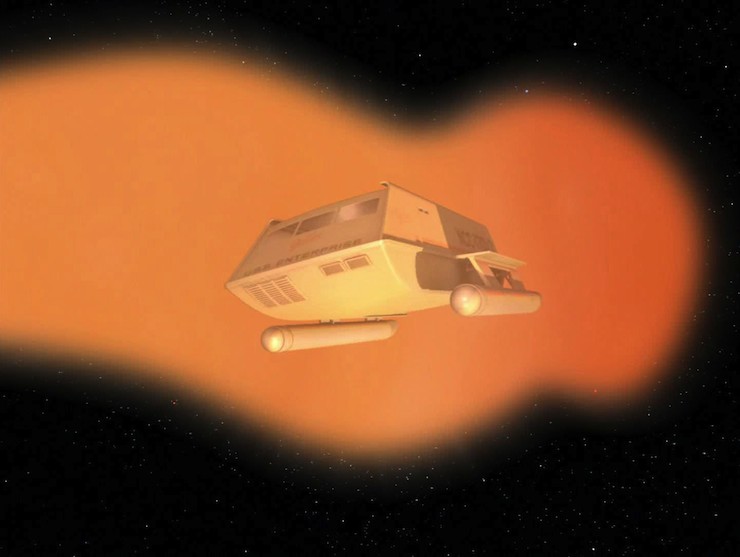

They encounter a large cloud of ionized hydrogen that is on a collision course for the Galileo. It envelopes the shuttle and brings it to a planet. McCoy and Hedford are both pissed—they need to get her to the Enterprise—but Galileo is powerless.

The shuttle is put down on a planetoid that has Earth-like atmosphere and gravity. The Galileo isn’t transmitting, so they can’t call for help. McCoy explores the area on foot, while Kirk and Spock check the shuttle: there’s nothing wrong with the shuttle, but nothing’s working. McCoy detects the same cloud of ionized gasses that Spock picked up in space.

And then a person cries out “Hello!” in English and runs toward them. “Are you real?” he asks—he recognizes them as being from Earth, and also recognizes Spock as a Vulcan, but hasn’t heard of the Federation. McCoy confirms that he’s human. He identifies himself as “Cochrane,” and he says that there’s a dampening field on the planet that keeps any power source dead.

Cochrane is particularly fascinated by the shuttlecraft. Kirk sends him off with Spock to show him the inner workings of Galileo, while Kirk and McCoy express their suspicions to each other—both his evasiveness and also his familiarity, as they each recognize him, but they’re not sure where from.

Cochrane takes them to his home, which he constructed from the remains of his ship that crashed on the world. While he’s preparing cold drinks (Hedford is getting feverish, which is not a good sign for her continued health), the landing party see the energy cloud (which looks like a giant floating omelette). Cochrane brushes it off with a line about seeing things as he pours the drinks. But Kirk demands an answer.

Finally, Cochrane explains. He was a dying old man when he encountered the energy being—he calls it “the Companion”—and it disabled his ship, brought him to the planetoid, and cured him of his ailments and made him permanently young again.

When Cochrane gives his first name, Zefram, they’re stunned to realize that they’re talking to the inventor of warp drive—who died 150 years earlier. But his body was never found. Cochrane says he wanted to die in space, so he got in a ship and just flew away until the Companion found him.

Cochrane also admits that the Companion brought the Galileo here to keep him company. He told the Companion that he was going to die of loneliness, and instead of letting him go, the Companion brought a bunch more people. Hedford, who’s already got a massive fever, has a fit. They put her to bed, and Cochrane asks what the galaxy is like now. Kirk tells him, and despite the fact that he’d age normally again if he left the planetoid, he wants to leave and see his legacy.

Kirk asks if Cochrane can communicate with the Companion, get it to help Hedford, who’s getting sicker. Meanwhile, Spock’s repair attempt on the Galileo is interrupted by the Companion, who destroys his instruments and fries the shuttle’s systems.

The Companion appears before Cochrane and envelopes him for several seconds. Kirk and McCoy speculate as to the relationship—talking to a beloved pet, symbiosis, possibly even love—and then Cochrane informs them that the Companion won’t help Hedford.

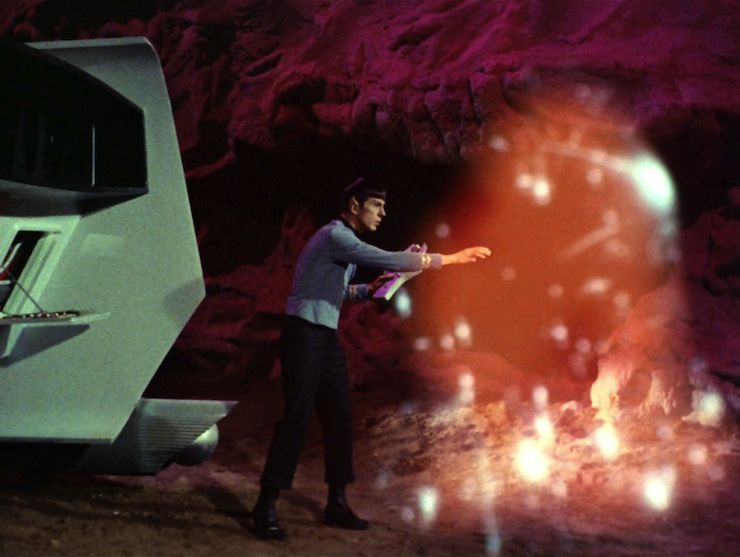

When Spock hasn’t checked in for a while, McCoy goes to investigate and finds Spock on the ground. Spock realizes that much of the Companion’s “substance” is electricity, which means it can be shorted out. He puts together a device that will disrupt the Companion. Cochrane is apprehensive—he doesn’t want to stay, but he doesn’t want the Companion hurt, either—but Kirk and McCoy convince him that it has to be done.

Cochrane summons the Companion. It envelopes Cochrane, Spock throws the switch, and then it turns red, hurting first Cochrane, then Kirk and Spock. Cochrane comes to and convinces the Companion to stop hurting them.

McCoy tells Kirk that diplomacy may work better than violence, and Kirk tells Spock to adjust the universal translator in the shuttlecraft, try to get it to understand the Companion.

Back on the Enterprise, Scotty engages in a search for the now-way-overdue shuttle. They pick up a particle trail, but it fades away. There’s no debris, no radiation, and no expelled atmosphere, which indicates to Scotty that they were towed. All they can do is continue on the course of particles Sulu picked up and hope they find them. When they reach an asteroid belt, they have to examine all of the planetary bodies in the field—though they start with the ones that have atmosphere.

Spock messes with the UT and then Cochrane summons the Companion. The floating omelette envelopes Cochrane once again, and Kirk speaks to it through the UT (which looks a lot like a sonic screwdriver), and it responds in a female voice. To Kirk and Spock, this changes everything—not a zookeeper, but a lover. Yes, they base this entirely upon gender. 1967. Sheesh.

Kirk tries to explain that it’s the nature of humanity to be free, just as the Companion’s is to remain on the planetoid. The Companion doesn’t get it, as they’ll stay healthy forever (she refers to aging as a “peculiar degeneration”). Spock is fascinated by this new life form, but they don’t have time to study it—especially since the Companion disappears in a huff, unwilling to let Cochrane go, and unwilling to let the others go, as “the man” needs their companionship.

Cochrane is more than a little squicked out by the whole thing. Kirk, Spock, and McCoy are confused by his disgust—it’s just an alien, what’s the big deal? Spock points out that it’s been a pleasant, mutually beneficial relationship for 150 years. Cochrane storms out, appalled at the lack of morality and decency in the future.

A feverish Hedford overhears their conversation, and is appalled that Cochrane is running away from love. Hedford is filled with regret that nobody ever loved her that way.

They try to talk to the Companion again. Kirk explains that Cochrane will cease to exist spiritually as long as he’s trapped on the planetoid, even though he’ll physically live on. Humans thrive on having obstacles to overcome; the Companion takes away all obstacles. Kirk plays on their differences to convince her to let him go—they’ll always be together, but always apart as well.

The Companion’s conclusion: if she’s not human, there can’t be love. So she becomes human by melding with Hedford. She’s cured of the disease and in perfect health—and she is now both Hedford and the Companion. She also repaired the Galileo—but that was her last act as the Companion. She is now powerless to stave off the “peculiar degeneration.” She will continue to age normally, as will Cochrane and the others.

Kirk contacts the Enterprise. Sulu locks onto his coordinates, and they can be there in an hour. Cochrane has come around to loving the Companion now that she looks like a person instead of a giant floating omelette—but she’s physically tethered to the planetoid. If she leaves for more than a day or two, she’ll die. Cochrane, therefore, decides to stay—it’s the least he can do after she saved his life. They kiss and stay on the planetoid where they can grow old together.

The landing party returns to the Enterprise when it gets there. They wish Cochrane and the Companion/Hedford well, promising not to say anything about him. When McCoy asks about the war on Epsilon Canaris III, Kirk blithely says that surely the Federation can find someone else to stop the war, and off they go.

Can’t we just reverse the polarity? We have the first appearance of the universal translator, the existence of which is a useful hand-wave for why everyone seems to speak English.

Fascinating. When Spock shows off his disruptor he says, “It cannot fail.” He then activates it and it totally fails.

I’m a doctor not an escalator. McCoy doesn’t seem to do much in the episode beyond keeping us apprised of Hedford’s failing health, but he helps Spock with his breakthrough regarding the Companion’s physical nature and he’s the one who talks Kirk into trying diplomacy.

I cannot change the laws of physics! Scotty is in charge of the Enterprise in Kirk and Spock’s absence, and he leads the search party.

Ahead warp one, aye. Sulu does the actual work of searching, and gets on the right track, but the Companion fixes Galileo before the Enterprise can complete the search.

Hailing frequencies open. Even though she’s a bridge officer and therefore should understand how searches work, Uhura asks Scotty lots of dumb questions and expresses concern about the search pattern in order for Scotty to be able to explain that stuff to the audience.

No sex, please, we’re Starfleet. Kirk says that the concepts of male and female are “universal constants,” and that the UT somehow just knew that the Companion was female. Right.

Channel open. “I could even offer you a hot bath.”

“How perceptive of you to notice that I needed one.”

Cochrane being polite and Hedford being rude. Hilariously, she never takes him up on the offer of a bath…

Welcome aboard. Glenn Corbett debuts the rather influential character of Cochrane, while Elinor Donohue plays Hedford. Elizabeth Rogers does the voice of the Companion—she’ll return in “The Doomsday Machine” and “The Way to Eden” as Palmer. Plus we’ve got recurring regulars James Doohan, George Takei, and Nichelle Nichols.

Trivial matters: The character of Cochrane will be referenced any number of times—e.g. “Cochrane distortion,” cited in the TNG episode “Ménage à Troi“—and be seen again as a younger man played by an older actor, James Cromwell, in the film First Contact as well as a couple of episodes of Enterprise. The Cochrane of the movie is far different from the one in this episode, but Glenn Corbett’s Cochrane had lived for centuries on a planetoid with only a giant flying omelette for company after his decision to die in space as an old man. Cromwell’s Cochrane hadn’t yet become the famous pioneer, and was instead a cynical drunken scientist living in a post-war mess.

Cochrane is regularly mentioned throughout the Enterprise series, and is credited in that show’s pilot episode, “Broken Bow,” with coining the Starfleet catchphrases about seeking out new life and new civilizations and boldly going where no one has gone before and so on.

Cochrane’s backstory was also developed by Judith & Garfield Reeves-Stevens in the brilliant novel Federation, which came out several years before First Contact, and more recently in Federation: The First 150 Years by David A. Goodman.

A sequel to this episode was done in issue #49 of Gold Key’s Star Trek comic by George Kashdan and Alden McWilliams, with the Enterprise again encountering a much older Cochrane and Companion/Hedford.

In addition to the James Blish adaptation in Star Trek 7, it was also adapted into a fotonovel, which also included an interview with Elinor Donohue.

Several scenes had to be re-shot due to the film negatives being damaged. However, in the interim between the original filming and the reshoots, Donohue had contracted pneumonia and lost ten pounds. They tried to hide this by judicious placement of her scarf.

To boldly go. “You are, after all, essentially irrational.” This episode makes me crazy.

On the one hand, it’s incredibly progressive. Cochrane’s attitude toward being in love with a giant flying omelette is pretty standard for 1967, but Kirk, Spock, and McCoy’s utter casualness about it is a joy to see. After all, here we are 50 years after Star Trek debuted, and there are still people who think anything other than a monogamous relationship between heterosexual people of different genders is icky. Cochrane’s situation with the Companion borders on bestiality in some senses (before you go “ooh, ick,” keep in mind that the same is true of Spock’s parents), but in the 23rd-century Federation it barely warrants a comment.

On the other hand, it’s depressingly traditional. Every time I hear Kirk say that the idea of male and female are universal constants, I want to throw my shoe at the screen. Never mind that it isn’t a universal constant even on this planet—there are genderless species out there, for starters—it shows an appalling lack of imagination. And the sexism is just awful. When they didn’t think of the giant flying omelette as female, it was considered at best someone keeping Cochrane as a pet, at worst his jailer. But as soon as the universal translator identifies the Companion as female (and how the hell does it do that anyhow? It’s a giant floating omelette, in what way can it possibly be considered female in any meaningful sense?????) everyone just assumes that it has to be a lover. Erm, why? If she’s female it has to be a romance because, y’know, female hormones and stuff. Except why would a female giant flying omelette react the same way as a female humanoid?

And then we have Hedford’s speech, where she says that she’s good at her job but has never known love, a speech that would never, under any circumstances, be given to a male character. (And why is she an assistant commissioner? Ferris in “The Galileo Seven” got to be a regular old commissioner, and he was just delivering medicine. Hedford is negotiating a peace on a warring planet, and she’s just an assistant? Seems to me that she has the harder job…) Having said that, in the end, Cochrane actually does choose a life of love over a life out in the galaxy he helped make.

Also, while the “Kirk, Spock, and McCoy go on all the landing parties” trope is pretty well entrenched at this point, it’s even stupider than usual here. All they were doing was ferrying a commissioner from a planet to the Enterprise—this really requires the captain and the first officer? Seriously?

Cochrane is an interesting character, and it’s fun to see the clash of values between him and our “modern” heroes, but ultimately this episode is maddeningly schizophrenic, jumping back and forth between a serious look at the future of humanity as filtered through the encountering of many aliens and taking an idiotic view of the future of humanity as filtered through the lens of 1967 values.

Warp factor rating: 5

Next week: “Friday’s Child”

Keith R.A. DeCandido‘s Heroes Reborn eBook novella Save the Cheerleader, Destroy the World is now available for preorder. One of six novellas tying into the new NBC series, Keith’s tale will be released on the 20th of November, and can be preordered from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or Kobo.

Baby steps. It’s probably partly because episodes like this slightly nudged open the door to the idea of unconventional forms of love that we’re able to take it so much farther 50 years later. At the time, they couldn’t have taken it much further than they did, not and still gotten it on the air. But it was a start.

I like this episode for its production values as well as its story. The score, the first of six TOS scores by George Duning (who studied at the same college of music as my father), is beautiful, lyrical, and romantic, one of my favorites. And the set of the Companion’s planetoid is probably the show’s most successful simulation of an outdoor environment on a soundstage, complete with clouds in the sky.

It does have its issues, though. As I remarked during the “Menagerie” rewatch, if the Federation had translator devices that could read the brain waves of alien energy clouds and convert them into English, why couldn’t they get more than yes/no beeps out of Pike? And, yes, there’s the question of how the Companion can have a gender that the translator can detect.

Christopher: I’m aware, but this is also a rewatch taking place in 2015, not a firstwatch taking place in 1967. Part of the point of the exercise is to rewatch the show with modern eyes. It’s more extreme than it was for TNG and DS9 (and Stargate, for that matter), but still examining it with contemporary eyes, as it were.

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

Funny thing is, I took that more as him being in love with a woman. I’m probably viewing it through highly personal lenses, but I see it as “oh my god, it’s a woman?!” I kind of see Cochrane as thinking of himself as gay up to that point (obviously not, because it’s 1967, but this is the story I tell myself), and then when he realizes the Companion is female it makes him question his own identity.

And then, of course, you get fluid sexuality dropped in at the end, as they ride off into the sunset together on white ponies. Or something like that. In any case, I take his horror at being more toward the fact that it’s female than the fact that it’s a giant flying omelette.

It’s been a while since I’ve seen this episode (more than30years in fact) and what really strikes me is the casualness with which the crew leaves a diplomat on their way to settle what we can only assume to be a major war (you don’t divert the equivalent of a Navy cruiser with all of its personnel to ferry someone to a war unless the stakes are really high) to be taken over by a non-corporeal alien of a type never encountered before on a desert planet, leaving the gestalt being so created shack up with an assumed long dead foundational genius of the Federation.

It also beggars belief that having done this, they would then promise to keep this series of events a secret!

Well, there’s your answer for why Cochrane looks so different in this episode and First Contact. Why it’s “Cochrane distortion” of course! Or… let’s just say he went through a… wait for it… metamorphosis if you will.

Despite the goofy parts of this one, I like it. Adds a nice bit of, as much as I hate to use this term, “world-building.”

@3: But how does that reading jive with the fact that Cochrane was also shocked that Kirk, Spock, and McCoy weren’t shocked?

To be fair, the great majority of animal species on this planet have distinct male and female sexes. Although how the UT could tell which one the Companion was is beyond me.

@8/ad: But as Keith pointed out, not all animal species on this planet have distinct sexes, or are limited to only two. (There’s a kind of microbe that effectively has seven sexes.) “The great majority” is not enough to constitute “universal,” because “universal,” by definition, means that there are no exceptions. (As in “universal translator,” a device that can translate every language.) The episode’s claim was that a simple binary model of gender is the only one that exists anywhere in the universe, and that is obviously not true.

“And then we have Hedford’s speech, where she says that she’s good at her job but has never known love, a speech that would never, under any circumstances, be given to a male character.”

It does provide some basis as to why Hedford would be accepting of sharing her body with the Companion, especially since it apparently let her die in the first place (the Companions actions with regard to Hedford are quite sketchy, jealousy to a semi-consensual deal with the devil for a “Grand Theft Me”).

However, is that speech really much different from Kirk’s “no beach to walk on” speech about his relationship with the Enterprise in “The Naked Time”?Perhaps the Companion decided it was female from its interactions with Cochrane’s mind over the years. It apparently should not have normally felt the kind of emotions it developed for Cochrane. Putting them in the human context of a male/female relationship justified to itself why it was feeling these things and the translator picks up on that human idea.Wonder exactly what happened to Cochrane to go from a goofy, irresponsible drunkard to this Captain America type.I think Kirk is going to regret his promise to Cochrane when Starfleet wonders how Kirk misplaced a deathly sick asst. Commissioner and not even have a body to bring back with him

For a change I don’t agree with the review at all. This is a beautiful episode and should get at least a rating of 7. Watched with my “modern eyes”, it holds up very well and contains very little sixties sexism.

First item: Hedford’s job. It’s silly that she’s just an “assistant commissioner”, but that’s a minor flaw. The writers gave her the job to stop a war! That wasn’t necessary for the story – they could have invented any other backstory for her.

Second item: “The idea of male and female are universal constants.” Totally silly. Agreed. But I don’t think it’s such a big plot point. After all, Kirk and McCoy are on the right track right from the beginning. When they see the Companion and Cochrane together for the first time, there’s this dialogue:

McCoy: Almost a symbiosis of some kind, a sort of joining.

Kirk: Exactly what I think. Not exactly like a pet owner speaking to a beloved animal, would you say?

McCoy: No, it’s more than that.

Kirk: Agreed. More like love.

So, no, they don’t consider their relationship “at best someone keeping Cochrane as a pet, at worst his jailer”. They understand what it is right away. The rest is TV drama – there has to be a turning point, so they come up with the female voice and the silly explanation. Points off for that, but no more than two :-)

Third item: “a speech that would never, under any circumstances, be given to a male character”. I don’t agree. Maybe they wouldn’t have a male character use the exact same words, but when I imagine it with switched gender roles, it works just fine. (Well, I guess they wouldn’t have made the genius engineer female in the sixties, but we’re watching it with modern eyes, so there.) As Crusader75 wrote, Kirk makes similar speeches on more than one occasion. And Cochrane makes the exact same decision as Hedford in the end, despite having been intrigued by the prospect of seeing the new world before. No gender bias here.

And there’s so much to like! As Christopher wrote, the setting is just great. And did we know that starship captains are trained to be diplomats? Also, I like the fact that Cochrane is from Alpha Centauri, so we get the information that there was some human space travel before the invention of the warp drive. (Sadly, First Contact changed that.) Finally, I also like Hedford’s outfit.

@3/MeredithP: That’s a cool interpretation, but does it fit with the way Cochrane treats Hedford when he first sees her (“You’re food to a starving man”)?

@10/Crusader75: Apart from being a goofy drunkard, the Cochrane from First Contact was also a brilliant inventor. We don’t get to see enough of him to really know him.