Many walk away from the most perfect city ever known, but never quite on the same route.

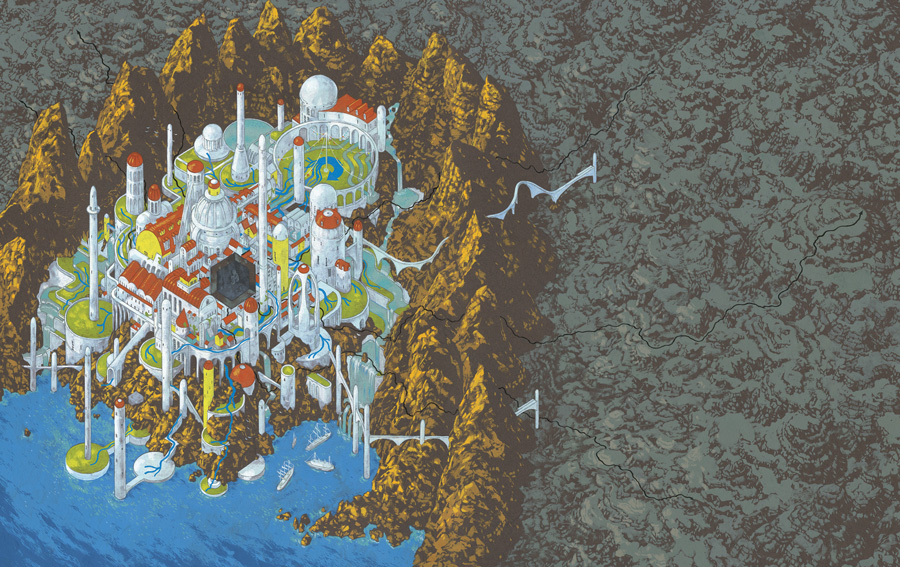

In the recently released Plotted: A Literary Atlas, artist and author Andrew DeGraff visualizes the stories of many famous literary works into singular landscapes, charting the progression of their characters all throughout. The results are beautiful maps that enhance classic works like Hamlet, Pride and Prejudice, Invisible Man, A Wrinkle in Time, Watership Down, A Christmas Carol, among others, while standing on their own as storytelling pieces.

We were particularly taken by DeGraff’s map for the classic Ursula K. Le Guin story, “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas.”

If you want to see the full 2 MB version, click here.

DeGraff explains the overwhelming appeal of visualizing Le Guin’s story. From Plotted:

“The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” is not intended as a happy story. The city is built on human misery. It has a heart of darkness that everyone must witness. But even bearing all of that in mind, this is a civilization that still shines more brightly than any that we have ever seen. As opposed to being built on the bones of millions like the most vaunted nations of the present day, Omelas has a body count of one. That is an impressive record indeed. But the story’s power seems to take advantage of that little cost. “One death is a tragedy,” Stalin is supposed to have said, “one million is a statistic.” One million is also truer to life but harder to see and compute. This single, unbearable life on display in Omelas forces us to reckon with our acquiescence in the brutal practices that remain a part of every civilization on earth.

This moral seems clear enough, but the story allows for a tremendous amount of complexity within its few pages. Ursula K. Le Guin won’t make sense of the story’s paradoxes for us. In fact, she forces us to partake of her creative act. She will not tell us about the technological sophistication of Omelas: “Perhaps it would be best if you imagined it as your own fancy bids… For certainly I cannot suit you all.” Much in this city seems to be negotiable in this fashion; drugs and sex certainly are. But whatever else changes, the child prisoner must remain. Here we have no choice — but we can walk away. Which brings us back to this question of guilt.

“One thing I know there is none of in Omelas is guilt.” This despite the fact that everyone within the city’s walls is guilty to the same degree. Guilty as both participants in a horrible crime, and guilty of a self-willed ignorance. But do we live in this city, or are we the ones who walk away? The narrator herself seems to occupy an ambiguous place. Sometimes she seems to discuss the appearance of the city with the knowledge and familiarity of a local (even defending its practices at one point), but at other times she seems to drift away, gaining the perspective of a visitor rather than a resident.

She seems to register what is strange about this place. But she cannot describe what lies beyond, in “the darkness” outside of Omelas, because each person there must make her own way. It is clearly an act of bravery to walk away, to stride into the unknown.

As readers, Le Guin provides us with the building blocks to construct the city of Omelas, but if we want to forsake it afterward, then we too have to strike out alone.