Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories—and some on his friends, too.

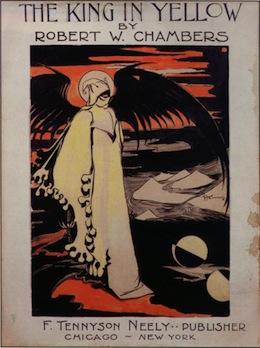

Today we’re looking at Robert W. Chambers’s “The Repairer of Reputations,” first published in 1895 in his short story collection The King in Yellow—not to be confused with the play, “The King in Yellow.” We hope.

Spoilers ahead.

This is the thing that troubles me, for I cannot forget Carcosa, where black stars hang in the heavens, where the shadows of men’s thoughts lengthen in the afternoon, when the twin suns sink into the Lake of Hali, and my mind will bear forever the memory of the Pallid Mask. I pray God will curse the writer, as the writer has cursed the world with this beautiful, stupendous creation, terrible in its simplicity, irresistible in its truth—a world which now trembles before the King in Yellow.

Summary: 1920: America’s a colonial power, having squelched Germany’s attempt to annex Samoa, and then repelled the German invasion of America itself. The military’s grown formidable; the coasts are fortified; Indian scouts form a new cavalry. Formation of the independent negro state of Suanee has solved that racial difficulty, while immigration’s been curtailed. Foreign-born Jews have been excluded; simultaneously, a Congress of Religions has abolished bigotry and intolerance. Centralization of power in the executive branch brings prosperity, while (alas) much of Europe succumbs to Russian anarchy.

In New York, a “sudden craving for decency” remakes the city, effacing the architecture of less civilized ages. One April day, narrator Hildred Castaigne witnesses the opening of a Government Lethal Chamber in Washington Square. Suicide’s now legal; the despairing may remove themselves from healthy society via this neoclassical temple of painless death.

Hildred next visits the shop of Hawberk, armorer, whose daughter Constance loves Hildred’s soldier cousin Louis. Hildred enjoys the sound of hammer on metal, but he’s come to see Wilde, the cripple upstairs. Hawberk calls Wilde a lunatic, a word Hildred resents since he sustained a head injury and was wrongly confined to an asylum. Since his accident Hildred has read “The King in Yellow,” a play that strikes the “supreme note of art,” but is said to drive readers mad. Widely banned, it continues to spread like “an infectious disease.”

Hildred defends Wilde as a superlative historian. For example, Wilde knows lost accessories to a famous armor suit lie in a certain New York garret. He also knows Hawberk’s really the disappeared Marquis of Avonshire.

Hawberk, looking panicked, denies his nobility. Hildred goes up to Wilde’s apartment. The man is tiny but muscular, with a misshapen head, false wax ears, and a fingerless left hand. He keeps a cat whose vicious attacks seems to delight him. Wilde is, ahem, eccentric. So is his career, for he repairs damaged reputations via some mysterious hold he has over employees of all classes. He pays little, but they fear him.

Wilde has a manuscript called “The Imperial Dynasty of America,” which lists Louis Castaigne as future ruler after the advent of the King in Yellow. Hildred’s second in line, and must therefore get rid of his cousin, and of Constance who might bear Louis’s heirs. His ambition exceeds Napoleon’s, for he’ll be royal servant to the King, who’ll control even the unborn thoughts of men.

At home, Hildred opens a safe and admires the diamond-studded diadem that will be his crown. From his window he watches a man dash into the Lethal Chamber. Then he sees Louis walking with other officers and strolls out to meet him. Louis is disturbed to hear that Hildred’s visited Wilde again, but drops the subject when they meet Hawberk and Constance, who walk with them in the new North River parks. They observe the impressive naval fleet; when Louis goes off with Constance, Hawberk admits Wilde was right—Hawberk found those missing accessories exactly where Wilde said they were. He offers to share their worth with Wilde, but Hildred haughtily replies that neither he nor Wilde will need money when they’ve secured the prosperity and happiness of a whole hemisphere! When Hawberk suggests he spend some time in the country, Hildred resents the implication that his mind’s unsound.

Louis visits Hildred one day while he’s trying on his crown. Louis tells Hildred to put that brass tinsel back in its biscuit box! He’s come to announce his marriage to Constance the next day! Hildred congratulates Louis and asks to meet him in Washington Square that night.

The time’s come for action. Hildred goes to Wilde, carrying his crown and kingly robes marked with the Yellow Sign. Vance is there, one of Wilde’s clients who blubbers about the King in Yellow having maddened him. Together Wilde and Hildred convince him to aid in executing Hawberk and Constance, and arm him with a knife.

Hildred meets Louis before the Lethal Chamber and makes him read the Imperial Dynasty manuscript. He claims he’s already killed the doctor who tried to libel him with insanity. Now only Louis, Constance and Hawberk stand between Hildred and the throne! No, wait, only Louis, because Vance runs into the Lethal Chamber, having obviously finished the ordered executions.

Hildred runs for Hawberk’s shop, Louis pursuing. While Louis pounds on Hawberk’s door, Hildred runs upstairs. He proclaims himself King, but there’s no one to hear. Wilde’s cat has finally torn out his throat. Hildred kills her and watches his master die. Police arrive to subdue him; behind them are Louis, Hawberk and Constance, unharmed.

He shrieks that they’ve robbed him of throne and empire, but woe unto them who wear the King in Yellow’s crown!

(An “editor’s note” follows: Hildred has died in the Asylum for the Criminally Insane.)

“Don’t mock madmen; their madness lasts longer than ours….that’s the only difference.”

What’s Cyclopean: Chambers isn’t much for elaborate adjectival contortions, but he makes up for it with rich and evocative names: Carcosa, Demi and Haldi, Uoht and Thale, Naotalba and Phantom of Truth and Aldones and the Mystery of the Hyades. They roll gracefully off the tongue—though the tongue may later regret speaking their dread names.

The Degenerate Dutch: Well, of course you’ve got to exclude foreign-born Jews, sayeth our narrator. For self-preservation, you know. But bigotry and intolerance have totally been laid in their graves. Getting rid of the foreigners and their pesky restaurants, of course, makes room for the Government Lethal Chamber. Surely a coincidence, that.

Mythos Making: Lovecraft took up Carcosa for the Mythos canon—as who would not, having glimpsed the wonder and horror of its twin suns? And the King himself may lurk in the background, unannounced for the sake of everyone’s sanity, in the Dreamlands.

Libronomicon: The Necronomicon may thoroughly alarm its readers, and its prose is at best self-consciously melodramatic. But “human nature cannot bear the strain nor thrive on the words” of The King in Yellow, a play which strikes the “supreme note of art.” (Though Lovecraft suggests that the fictional play was inspired by rumors about the real book.)

Madness Takes Its Toll: If a doctor mistakenly places you in an asylum after a head injury and incidental reading of The King in Yellow, you must of course seek vengeance.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

This is my first read of Chambers’ classic, and the opening segment did not fill me with hope for the rest of the story. My ancestors are such a threat to the country, yes, thank you—I can see why Howard is so impressed, but I think I’ll be rooting for the monster of the week.

But then I start to notice that this perfect, blissful future America seems to have a lot of militarism that the narrator takes for granted. Perhaps that first section is intended to be read with a doubtful eye—maybe? This would certainly be a more palatable story if the narrator wasn’t intended as reliable.

Then there’s the architectural updating of New York and Chicago, complete with getting rid of the trains—Chambers was a Brooklyn native and doesn’t seem to have had Lovecraft’s horror of the place. I don’t think any real New Yorker could write seriously and approvingly about breaking the ethnic restaurant scene, even in 1895.

“It is believed that the community will be benefited by the removal of such people from their midst.” And yes, what we have here is not so much unthinking bigotry as extraordinarily sharp satire. Sharp enough to cut without you even noticing until you’ve bled out.

Ultimately, this may be the alien-free story I’ve enjoyed the most from the reread. I don’t creep easily, but lord, this thing is creepy! Not only the brain-breaking play, but the mundane details of politics and everyday life. And everyday death: the gentility of the Lethal Chamber, and the government’s gentle willingness to back the nasty insinuations that depression whispers in the night. Keeping a murderous cat, or reading a life-destroying play, seem almost redundant. Perhaps that’s the point.

And then there’s Hildred, so very elegantly unreliable. The moment when the “diadem” is revealed to be delusional, and yet something real is definitely going on…

Or… frankly, I’m still trying to figure out what actually is going on. What can we count on, through the filter of Hildred’s King-touched ambitions? The play, certainly and ironically. It exists, and it’s a brown note (obligatory warning for TV Tropes link). The Lethal Chamber, too, seems nastily real. And behind it, the militarized dystopia that Hildred never acknowledges.

But is the King real? Yellow-faced Wilde seems to serve him—but Hildred serves the creature without ever meeting him, and Wilde might do the same. Perhaps all the play’s readers orbit a vacuum. Or perhaps the King’s empire is a sort of perverse micronation, real to the degree his subjects make it real.

Wilde’s role as Repairer of Reputations is also pretty ambiguous. We see only one of his clients, another King-reader who seems as out of touch with reality as Hildred. If his reputation were either damaged or repaired, would he even know? Wilde’s other clients, like the ten thousand loyal subjects ready to rise in Hildred’s coup, may be merely notes on a ledger.

But then there’s Wilde’s uncanny knowledge—indisputably confirmed by other witnesses. He wouldn’t be nearly so terrifying if he could be dismissed as a complete charlatan.

So much more to say, but I’ll limit myself to asking one final, alarming question that’s still bothering me days later. Plays are normally intended to be performed. Anyone who’s both appreciated Shakespeare on stage, and read him in the classroom, knows that the reading experience is a pale shadow of actually sitting in a darkened theater watching the acts unfold. So what happens to people who see The King in Yellow live?

And what effect does it have on those who act in it? Breaking a leg might be a mercy.

Anne’s Commentary

Unreliable narrator much? Or, maybe, worse, not so much?

At first I thought “The Repairer of Reputations” was alternate history based on World War I, but then I noticed its date of publication—1895! That makes it more of a “prescient” history, or maybe a near-future dystopia? A central question is how much, if any, of Hildred’s observations are factual within the context of the story. Put another way, how much does he make up or misinterpret in his grandiose paranoia? All of it? None of it? Something in between?

The story’s told in Hildred’s twisted and twisting point-of-view. We don’t know until the last paragraph that the story’s probably a document he wrote while incarcerated in an asylum, for the material has an unnamed “editor.” My sense is that we should assume Hildred’s account is all his own, unaltered by the editor, who may just be a device for letting us know Hildred has died in the asylum.

Teasing out all the clues to the internal “veracity” of the tale would take more study than I’ve given it. I’m going with a historical background that’s basically true rather than the delusional construct of the narrator. Hildred describes what for him seems a utopia of American exceptionalism: growing military power, secure and far-flung colonies, centralized power, urban renewal, religious tolerance and prosperity, hints of eugenics in the exclusion of undesirable immigrants and the new policy of letting the mentally ill remove themselves from the national gene pool. The description of the Lethal Chamber opening, complete with marching troops and Governor’s speech, seems overelaborate for mere delusion, and Constance later says she noticed the troops. Overall it seems we can trust statements of the “sane” characters, as reported by Hildred. Other examples include all the warships in the North River, which everyone notices, and the “biggie clue” to Hildred’s instability—how Louis sees the “crown” as tinselly brass, the “safe” as a biscuit box.

Does Chambers share Hildred’s enthusiasm for the new America? I’m thinking no, or at least, not entirely—this vision of the future is not wish fulfillment for the author, though it may be to some extent for the narrator. Chambers does some deft juxtapositioning in the opening paragraphs. One moment Hildred lauds the death of bigotry and intolerance brought about by a “Congress of Religions;” another, he gloats that immigration and naturalization laws have been much tightened. Foreign-born Jews are right out. The ultimate in segregation has put the black population in its own independent state. The millennium has arrived! Um, except for most of Europe, upon which Russian anarchy has swooped, vulture-like. But hey, self-preservation comes first! Isolationism, baby, with a beefed-up military to preserve it.

And the Government Lethal Chambers? Act of mercy or potential killing boxes for any “despairing” enough to oppose the new order? Oops, John Smith was found dead in the Washington Square Chamber. Poor guy, all his silly antigovernment articles must have been a sign of incipient suicidal madness!

Not that I’m paranoid or anything, like Hildred. Yet as the epigraph tells us, madmen are just like us, only they’re mad for longer. Maybe practice makes perfect, and long-term madmen come to see more than the sane? Such as the truth encapsulated in “The King in Yellow”?

Everybody thinks Hildred is crazy except Wilde, who’s also held to be crazy. But Chambers goes to some lengths to show us Wilde’s no mere lunatic. He DOES know the seemingly unknowable, such as where those lost armor accessories are. Is his claim that Hawberk’s the Marquis of Avonshire just babbling? Sure, Avonshire’s a fictional place in our world, but the world of the story? And what are we to make of Hawberk and Constance’s strong reactions to the claim? What about Hawberk’s name? A hauberk is a mail shirt—pretty convenient for “Hawberk” to be the real name of an armorer.

Wow, barely scratched the surface as space dwindles. Last thought: “The King in Yellow” is, in story context, a real play that causes real madness in readers. This notion’s supported by how Louis speaks of the dreaded book. Something’s going on here, but is the King-inspired madness a shared mania or divine inspiration too intense for human endurance? Is the King coming, and do trends in America prepare for His advent?

The cat. No time for her, but she’s an interesting touch. Ill-tempered feral? A projection of Wilde’s lunacy? A familiar sent by the King and on occasion expressing the King’s displeasure?

We’ve got quite the puzzle box here.

Next week, we cover two short Dreamlandish pieces: “Memory” and “Polaris.” By the list we’re working from, these are the last of our original Lovecraft stories that aren’t collaborations or juvenilia! We’ll follow up with the “Fungi from Yuggoth” sonnet cycle—and from there, start a deeper dive into Howard’s influencers and influencees, interspersed with the aforementioned collaborations and early fragments. Thanks to all our readers and commenters—this has been a remarkable journey so far, and promises to continue with all the squamousness and rugosity anyone could ask for.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint in Spring 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

I can’t begin to imagine what reading something as wonderful and terrifying and strange as “The Repairer of Reputations” would have been like back in 1895.

Lovecraft on Chambers: in “Supernatural Horror in Literature” Lovecraft spends almost all of his Chambers discussion on “The Yellow Sign”: regarding The King in Yellow as a whole he says that it “really achieves notable heights of cosmic fear in spite of uneven interest and a somewhat trivial and affected cultivation of the Gallic studio atmosphere made popular by Du Maurier’s Trilby.”

The Founder of Frustrations: I’m not the only reader to have been disappointed by Chambers’s (entirely understandable) decision to turn to writing popular, non-weird works in his later career. Quoth Lovecraft:

“One cannot help regretting that he did not further develop a vein in which he could so easily have become a recognised master.”

A question from Michael Moorcock (Ansible 342): “If I send my World Fantasy awards back, do I get a replacement?”

Proof of concept: certain commenters and re-readers may be interested to know that Alan Dean Foster had a book release in December (not that one). I haven’t read it but Oshenerth is a “heroic fantasy set entirely underwater”. There is now no good reason why a comedy-of-manners set in Y’ha-nthlei couldn’t be written.

I can never decide just how much of what the narrator says to believe. America as a near future colonial power is certainly plausible from 1895 and warships in the river were not an uncommon sight at the time of writing. The rest of it, I haven’t a clue. Right now, I don’t think any of it is true. Hawberk’s reaction to that whole Duke of Avonshire thing is probably a nervous reaction to a wild statement by someone he thinks might be a dangerous lunatic. Is he really an armorer or is that something Hildred cooked up in his madness based on the name? The death chambers could just as easily be public telephone booths for all we know.

Oddly, there are only 4 weird tales (or 6, depending on how you define it) in the collection The King in Yellow. Most of the rest of the stories are about art students in Paris (which Chambers knew something about, having been one). I wonder what all those people who ran out and read it after True Detective made of it. I’ve also read The Maker of Moons. It’s all right, but nothing like the KiY stories. Maybe a little reminiscent of A. Merritt.

At some point, I think we ought to read “In the Court of the Dragon”. If I’m remembering correctly, it shares some similarities with “Erich Zann” or at least influenced it strongly.

Carcosa was invented by Ambrose Bierce in a story published 4 years before this one. Chambers expanded on it greatly, but you can see a lot of the Bierce in the way it’s used in the mythos by later writers.

@2: Ah, True Detective: for a brief, glorious, moment, everyone seemed to be wondering what The Conspiracy Against the Human Race was.

My favourite story from this cycle is “The Yellow Sign”: I imagine that if we wait a short while a fan of “The Mask” will show up.

Readers who just want the weird fiction of Robert W. Chambers: may be interested to know that Chaosium’s The Yellow Sign and Other Stories contains all of his weird works and comparatively little about art students.

@3: Oh, The Yellow Sign is definitely the best. I just think “In the Court of the Dragon” might have influenced “Erich Zann” with the odd, out of the way corner of the city.

I.N.J. Culbard’s graphic novel adaptation of The King in Yellow is worth investigating.

I read the full King in Yellow (the collection, that is) last year after finishing up True Detective S1 (and I still wish, oh how I wish, that they would’ve gone full Cthulhu at the end there; but that’s another topic). I’d read Repairer of Reputations in particular, and maybe a couple of the other stories, before in various anthologies. Reading it this time, Repairer struck me as particularly surreal given the whole SF-set-in-1920-written-in-1895 thing. Had there been much future-set SF at that point?

Agree that the second half of the book was much weaker.

Also am I the only one who immediately flashed to Futurama’s suicide booths?

SchuylerH @@@@@ 1: My wife agrees with you–she wants a comedy of manners about Deep Ones and Shoggoths working together to deal with climate change and ocean acidification.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 2: And Wikipedia thinks they’re subway entrances. I’m not convinced–although come to it, I’m not sure anyone else in the story corroborates their existence. Unless you count the various people speechifying at the grand opening, and Hildred doesn’t usually misreport dialogue, just misinterpret it. Or so I infer. Oh, I give up: nothing is real and the walls of reality are caving in.

Hoopmanjh @@@@@ 6: Looking Backward came out in 1888 and influenced a lot of similar stories over the next few years. I suspect the opening here is very consciously mimicking that genre. You think you’re reading one thing, and then…

The Time Machine, however, is not an influence here; it came out the same year.

OK, now I’ll have to add Looking Backward to the Ever-Expanding TBR Pile o’ Doom.

I first encountered what I think of as “the Hali mythos” when I got the Dover edition as a teen. I could not make much sense out of the stories, and with this one there is still difficulty, but the wondrous little allusions/images stick to the roof of the mind. I’ll get back to that.

I wonder if we are supposed to think that Vance lost it, came back and killed Wilde instead of Hawberk and Constance, and then offed himself? If not, that poor cat could have been the savior of the world.

Where did Wilde get the dynasty notes [and the missing armor info], and where did Hildred get his crown and robe? What sort of a safe has a timer that limits how long it can be open? Was that Chambers’ idea of futuristic tech? He sure didn’t have much else in the way of sfnal tech, other than the lethal chambers–a nice ironic term, given his name. All right, I don’t know much about safes.

If Hildred really was crazy, was it caused by the horse accident or by having been wrongly locked up due to a wrong diagnosis? I’ve heard enough about the horrible treatment of mental patients to wonder about that. He can tell when his brother is being patronizing–or is this just more paranoia?

Why did Wilde’s death derail Hildred’s coup plans? Was Wilde named after the notorious writer across the pond?

The idea of a mind-blasting book hits very close to home for me. In my already troubled teens I read something that scared me out of a year’s growth, even though it was (supposedly) fiction. So HPL and Chambers were a bit of a relief.

As to the imagery, I found the Lake of Hali a more interesting character than the people in the play, or the story for that matter, with the possible exception of Hawberk, an artisan rather like me. I once worked in a place where machine parts were cleaned by submersion in a tank of hot trichlor, and there was a layer of sparkling mist above the surface that’d slosh back and forth in waves when disturbed, and it made me think of Hali every time. Someone elsewhere suggested that it was the source of the transformative liquid in “The Mask”. Too bad Culbard didn’t do more with that–but I wonder how anyone could see what they were doing, because their eyes had no pupils!

I liked the black stars also–maybe they’re the missing pupils…

If my ancestors would’ve been shut out, it’s not a utopia to me.

Aerona @@@@@ 10: Funny how we’re always so unreasonable about that kind of thing.

Great stuff, as always. My random thoughts:

How good is it?: Pretty damn great. For my money, “Repairer of Reputations” is one of the greatest American weird tales of the 19th century, right up there with things like “The Fall of the House of Usher” and “The Death of Halpin Frayser.”HPL simply got it wrong when he placed “The Yellow Sign” first among Chambers’ stories.

What the Hell is going on?: We definitely have an unreliable narrator here, but how unreliable is he? Is the story actually set in 1920? Are the details (suicide booths, etc) real? I tend to think not. I think that Hildred has imagined all the futuristic business. The key lies in another story in the collection, “The Yellow Sign.” The narrator of “The Yellow Sign” knows Hildreth:

“What is it?” I asked.

“The King in Yellow.”

I was dumfounded. Who had placed it there? How came it in my rooms? I had long ago decided that I should never open that book, and nothing on earth could have persuaded me to buy it. Fearful lest curiosity might tempt me to open it, I had never even looked at it in book-stores. If I ever had had any curiosity to read it, the awful tragedy of young Castaigne, whom I knew, prevented me from exploring its wicked pages.

“The Yellow Sign” is clearly not set in 1920. There are no suicide chambers, etc. Indeed, the tale might be set prior to the 1890s, as evidenced by this reference:

“And you, Thomas?”

The young fellow flushed with embarrassment and smiled uneasily.

“Mr. Scott, sir, I ain’t no coward, an’ I can’t make it out at all why I run. I was in the 5th Lawncers, sir, bugler at Tel-el-Kebir, an’ was shot by the wells.”

The battle of Tel-el-Kebir was an actual battle, and it happened in 1882. Since Thomas is described as a “young fellow,” the story can’t be set in 1920, as that would mean that he was in his 60s. Assuming that Thomas was around 18 in 1882 (he might have been younger), that would mean that he was born around 1864. So, that would imply that both “Yellow Sign” and “Repairer” are set in the late 1880s-early 1890s.

Fascism avant la lettre: It’s quite impressive how Chambers manages to describe a fascist regime long before Mussolini and Hitler. There’s the erosion of representative government (“ the gradual centralization of power in the executive”: say goodbye to Congress and antiquated ideas about separation of powers), the emphasis on militarism, the removal of undesirable elements, etc. Most fascinating, though, is how Chambers anticipates the fascist desire for opulence and grandeur:

. Everywhere good architecture was replacing bad, and even in New York, a sudden craving for decency had swept away a great portion of the existing horrors. Streets had been widened, properly paved and lighted, trees had been planted, squares laid out, elevated structures demolished and underground roads built to replace them. The new government buildings and barracks were fine bits of architecture, and the long system of stone quays which completely surrounded the island had been turned into parks which proved a god-send to the population. The subsidizing of the state theatre and state opera brought its own reward. The United States National Academy of Design was much like European institutions of the same kind. Nobody envied the Secretary of Fine Arts, either his cabinet position or his portfolio.

Recall Hitler’s use of the architect, Speer. Not to mention Hitler’s plans for building a grand capitol after the war…

The Significance of Yellow: All over the place in the 1890s. There’s THE YELLOW BOOK (1894-97) coming out of London, the standard bearer in the Anglosphere for all things decadent and aesthetic. The Yellow Press (the term emerges in the middle of the decade). And then there’s Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s (talk about a name out of a Lovecraft story!) “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892), which HPL praised quite highly:

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, in “The Yellow Wall Paper”, rises to a classic level in subtly delineating the madness which crawls over a woman dwelling in the hideously papered room where a madwoman was once confined.

Poisoned books: Let’s see, there’s Huysman’s 1884 A REBOURS (AGAINST NATURE/AGAINST THE GRAIN), the real world prototype. Which appears in Wilde’s PICTURE OF DORIAN GRAY (1890) as the book that leads to the eponymous protagonist’s downfall. And Chamber’s KING IN YELLOW appears in 1895, continuing the chain.

Mr Wilde, I presume: Is Wilde, the self-styled “Repairer of Reputations” a sly nod to Oscar Wilde? Interestingly, the court-cases that ruined Wilde’s reputation occurred in 1895. That’s probably cutting things too close for THE KING IN YELLOW. Hence, any Wildean influence probably stems from Wilde’s pre-1895 work and reputation.

The internet just ate my comment! Let me explain. No, there is too much. Let me sum up. ;)

“The Repairer of Reputations” = cool and creepy.

Oscar Wilde reference: sounds legit.

I like Lovecraft’s liking of “The Yellow Wallpaper” but wonder how closely he read the story as there is no direct textual evidence of the infamous room being occupied by a “madwoman” before the narrator takes residence.

It’s very difficult to riff on performances of The King in Yellow as a play without going into enough detail for the whole scenario to cease to be creepy. The best I’ve found is over at the SCP Foundation, SCP-701, The Hanged King’s Tragedy, which wisely does not literally use the lore from Chambers and makes up its own play from a conglomeration of Shakespeare and the plot of ‘The Repairer of Reputations’.

IMO the weirdest thing that has ever happened to the whole Bierce-Chambers-Lovecraft lore set is the way Marion Zimmer Bradley just took and used all the names in the completely-non-supernatural-horror Darkover books. There is literally a Lake Hali on the planet Darkover, and it is literally a lake of mist. Characters are named things such as Cassilda and Camilla, and other related words turn up over and over again. Hastur is the ruling feudal lineage of the world. And yet nothing is ever done with any of those resonances; they just keep happening, over and over. I can’t reread Bradley since the news about her history as an abuser came out, but I used to have serious cognitive dissonances with Darkover anyway, because, just, what even.

Yellow was the color of shame. In the middle ages, prostitutes were recognizable by yellow clothes. In Nazi Germany, Jews had to wear a yellow star.

I recognize the names Hali and Aldones from Darkover.

@jaimew, #13, re: The Yellow Wallpaper: there is, actually, and I once nearly failed an English exam on account of not seeing that evidence; Lovecraft is regarded in academia as one of the first critics to have read the story thoroughly. I shan’t go into word-by-word exegesis here, though, as it’s something of a derail. Hopefully this reread will get to that story eventually.

@Rush-That-Speaks: I don’t want to derail the conversation either (anyone who wants the conversation to stay “railed,” please feel free to skip this post) but I have to say that your English prof. seems to have a particular interpretation of that story, as does Lovecraft.

I assume you’re referring to the narrator describing the infamous room as having bars on the windows and rings and stuff on the walls (which leads her to the conclusion that it was once a gymnasium). Also, the bed is nailed down. However, talk about an unreliable narrator! At one point in the story she discusses how badly the supposed children treated the room, saying “the bedstead is fairly gnawed.” However, later she says she got so angry that she bit the bedstead but it hurt her teeth. I got physical chills when I first read that. How much can we trust ANYTHING she says? “The Yellow Wallpaper” is a staple in my lit. classes and I LOVE pointing that out to my students and seeing the “OH CR@P” moment in their eyes… :D

The Significance of Yellow: All over the place in the 1890s. There’s THE YELLOW BOOK (1894-97) coming out of London, the standard bearer in the Anglosphere for all things decadent and aesthetic.

And Gilbert & Sullivan skewered the Aesthetic Poets as “greenery-yallery (i.e. yellowy), Grosvenor Gallery, foot-in-the-grave young men” in “Patience”.

I don’t think that this is Chambers’ idea of a Utopia! It’s being described by a madman, remember…

And what on earth is an armourer doing in a futuristic New York?

I come up with a different theory about this story every time I read it, though I generally tend to the opinion that the futuristic society is entirely in Hildred’s mind because, as pointed out @12, the future America isn’t consistent with the setting of other stories in the cycle. Perhaps Sacheverell Sitwell had it right: “In the end it is the mystery that lasts, and not the explanation.”

Also, we need to reread “The Yellow Wallpaper”.

@6: I flashed to Robert Sheckley’s Immortality, Inc..

@9: I wonder about the safe. At one point, I wondered whether the alarm served a similar purpose to radiation film badges by letting Hildred know that it really is time to put the mind-warping artefact away again.

@14: It’s notable that MZB wrote her master’s thesis on the later works of Robert W. Chambers: The Necessity for Beauty: Robert W. Chambers & The Romantic Tradition.

Regarding your comments on Darkover, well, that’s part of the reason why I always preferred Andre Norton.

I think trajan23 makes a good case @12 that absolutely nothing in this story is real within the context of the cycle. There’s also the underlying assumption in Hildred’s version that America has a hereditary monarchy/aristocracy which has either been supplanted by a new government or set aside in a dynastic struggle. I wonder if Chambers knew about Emperor Norton. He might have learned about him from the Robert Louis Stevenson novel The Wrecker. That could explain why California and the Northwest weren’t going to support Hildred’s revolution.

@18 ajay: An armorer in this context is probably someone who produces arms, not armor. He could be a gunsmith or a swordsmith (military swords were still a thing, despite the lessons of the Civil War). Of course, he could just as easily have been a haberdasher or a tailor in reality.

#20, good catch, about Emperor Norton.

Hawberk could be working for various museums, or involved with something on the order of SCA and still operating under the fascist regime, as some sort of a distraction for (some of) the masses. Then again, if Hildred really is crazy all thru, the Lethal Chambers could in fact be restrooms in the park. His not going into one results in him being full of…well, anyway.

Agreed about Bradley. Intrigues among people didn’t interest me that much, and there were some other scenes that made me jam the book(s) back into the shelf. And I was hoping someone would do a scientific investigation of the lake.

Where did Chambers get the idea? He could have simply seen a hollow full of morning ground fog, which can look like waves sometimes. Black stars–astronomical negatives, or a flock of dark birds suddenly taking flight–a bit spooky, if you are alone in an isolated area and they are crows. White shadows, in some of his other stories, that’s anyone’s guess.

Angiportus @@@@@ 9: Wilde’s the only one with (hypothetical) access to the 10,000 (hypothetical) people who will rise up in Hildred’s support. No Wilde, no way to get them the Sign.

RushThatSpeaks & JaimeW: I’m not sure where anyone gets the idea that these comment threads run on rails. Derail away!

And yes, we’ll definitely have to look at “The Yellow Wallpaper,” both because early weird fiction seems pretty unbalanced in the testosteronish direction, and because it’s the only one I was ever assigned in English class. I don’t remember any indication that the room was previous occupied by a madwoman, but then the same English teacher entirely skipped over Ahab’s status as a failed prophet in favor of obsessing over the symbolism of the gold coin nailed to the mast in Moby Dick, so.

Ajay @@@@@ 18: He mentions doing work for the Met. This is actually extremely plausible–one of my parents’ friends does tapestry weaving for the Cloisters. New York is a good place to practice ancient arts, and is likely to continue so through any number of regime changes.

SchuylerH @@@@@ 19: We do have some evidence that the safe is, in fact, an alarm-free biscuit box. Why Hildred imagines the alarm, then, is its own intriguing question.

DemetriosX @@@@@ 20: Ooh. Nice catch on Norton. And I recall from Sandman that Norton overcomes both Delerium and Desire, so he’d probably do well even in a universe with The King in Yellow.

The more I think about it, the less likely I find a connection to Emperor Norton to be. Chambers was very much a New Yorker (with strong New England roots, descended from Roger Williams, which must have pleased Lovecraft), while Norton was a fixture of San Francisco. Norton did inspire a character in Huck Finn, but I don’t know how well that was known, and makes a brief cameo in the RLS novel I mentioned @20. He gets a couple of paragraphs to demonstrate how kind San Franciscans are, but there’s no indication that he’s a real person at all and not made up for the story. I suppose he might have read about Norton in some California travel book.

But I think the trope of a lunatic thinking he’s Napoleon was already well established. He could just as easily have been building on that. OTOH, there’s absolutely nothing stopping an enterprising mythos writer from drawing a connection.

@22: I also wonder why Hildred finds it necessary to wait three and three quarter minutes before opening the “safe”. This whole story could be put under “Madness Takes Its Toll”.

@23: Norton was famous enough to get a large obituary on page 5, column 2 of the January 10, 1880 New York Times. It’s quite probable that Chambers had heard of him.

@jaimew, #17: Sure, there are the ‘rings and things’, but there are also the apparitions of a woman that the narrator sees behind the wallpaper, as if the wallpaper were bars. However, the clincher is in the narrator’s ranting at the end of the story: “‘I’ve got out at last,’ said I, ‘in spite of you and Jane. And I’ve pulled off most of the paper, so you can’t put me back!'”

The only way this sentence makes any damn sense is if Jane is the name of the original narrator, because there is no one else in the entire story who could possibly be being referred to here– all of the people who have been working so hard to keep the narrator in the attic are male except the original narrator, who goes along with them despite her better judgment, who trusts the men over herself because she wants to ‘get better’. Therefore she is, paradoxically, leaving herself open to the forces in the attic by the very effort she is using to keep them away. And if Jane is the original narrator, then Jane isn’t the one talking any longer there at the end, or not the only one, as the other appears to have access to Jane’s memories. The other must have come from somewhere, indicating that the apparitions in the wallpaper were an accurate perception of an entirely real ghost. Who is quite clearly mad, and was, evidently, trapped…

I remember that now! My interpretation at the time, I think (or the class’s interpretation, impossible to be sure 25 years later) was that the “new narrator” is the inner (perhaps madder) self of the old one, having thrown off her name along with the expectations of the men and society. And that the images behind the wallpaper are Jane’s own perception of herself as a prisoner.

Ghost story, or madness as liberation? Or both? Definitely have to move this one up in the reading queue!

I kind of figured that WIlde was key to Hildred’s hopes. But the crown and safe might have been real, brought by Wilde to influence Hildred,and Louis too shallow to recognize them. Maybe. I didn’t feel like trusting Louis either.

An interesting detail is how Hildred had a sensory oddity, liking the sound of the armorer’s work so much, the sight also. I am not sure if he was like that from the beginning or not, but inclined to suspect the former. Some people have an unusual esthetic trope or two–I’m one of them, for me it is shapes.

The Yellow SIgn, which I found an incoherent mess, mentions “young Castaigne”, which if it means Hildred must mean that happened later, but no mention of any (then) futuristic date. I get the feeling Chambers wasn’t trying that hard for consistency. In “The Mask”, one reader of the play emerges unscathed, finally, and gets the girl too.

I don’t recall the Parisian stories in the original collection, but the ones in the Dover edition are a mishmash of “Dammit, chemistry/biology/geology doesn’t work like that”, romance or attempts for same, digs at “bluestockings” unless they are pretty and cheerful, a story that’s a ripoff of Bierce’s Owl Creek Bridge one, with sickly Native American exoticism mixed in, mysterious Asian menaces, and a beautiful evocation of the northern woods (which I understand would actually be a bug-infested hell in summer.) We even have mountains sticking out of the atmosphere (in Maker of Moons), although that depends on where you decide the atmosphere ends off. A composite creature as well, many little arthropods combining into one.

I’ve got one medical-type question that someone here might be able to answer–if someone was branded with a hot iron on the forehead, such as to leave a mark on the skull itself, would the heat be enough to fry part of the brain inside? (“The Messenger”)

Angiportus @@@@@ 27: I would think that you’d need to be specifically trying for brain damage in terms of heat and duration–the levels needed to mark the skin or even the skull probably wouldn’t do it–the skull is thick for a reason. Also, if you could cause brain lesions that way, I strongly suspect it would show up more often in neuroscience textbooks, which are full of deeply upsetting things happening to brains. But I’m a cognitivist, and may have missed something.

Writers: you wouldn’t want to be in a room with anyone else who thought about these things.

More random thoughts and observations:

@@@@@ 27:” The Yellow SIgn, which I found an incoherent mess, mentions “young Castaigne”, which if it means Hildred must mean that happened later, but no mention of any (then) futuristic date. I get the feeling Chambers wasn’t trying that hard for consistency.”

Yeah, I went into that at #12. “Yellow Sign” clearly occurs sometime after “Repairer,” and the world of “Yellow Sign” is clearly not the dystopian 1920s depicted in “Repairer.”

RE: Consistency,

Actually, there’s quite a bit of internal consistency/continuity. Chambers is just subtle about it. Besides the already discussed reference to Castaigne in “Yellow Sign,” there’s also the matter of Boris Yvain, who is discussed in “Repairer” and plays a role in “The Mask”:

It was, I remember, the 13th day of April, 1920, that the first Government Lethal Chamber was established on the south side of Washington Square, between Wooster Street and South Fifth Avenue. The block which had formerly consisted of a lot of shabby old buildings, used as cafés and restaurants for foreigners, had been acquired by the Government in the winter of 1898. The French and Italian cafés and restaurants were torn down; the whole block was enclosed by a gilded iron railing, and converted into a lovely garden with lawns, flowers and fountains. In the centre of the garden stood a small, white building, severely classical in architecture, and surrounded by thickets of flowers. Six Ionic columns supported the roof, and the single door was of bronze. A splendid marble group of the “Fates” stood before the door, the work of a young American sculptor, Boris Yvain, who had died in Paris when only twenty-three years old.

(“Repairer of Reputations”)

We sat in the corner of a studio near his unfinished group of the “Fates.” He [Boris Yvain] leaned back on the sofa, twirling a sculptor’s chisel and squinting at his work.

[…..]

We were proud of Boris Yvain. We claimed him and he claimed us on the strength of his having been born in America, although his father was French and his mother was a Russian. Every one in the Beaux Arts called him Boris. And yet there were only two of us whom he addressed in the same familiar way—Jack Scott and myself.

(“The Mask”)

And the Jack Scott referenced above is the narrator of “The Yellow Sign.”

Bearing all this in mind, the internal chronology looks like this:

1.“The Mask”: The Fates is unfinished.

2.Repairer of Reputations”: Boris Yvain is dead and the Fates is finished.

3. “The Yellow Sign”: Hildred Castaigne is dead.

THE YELLOW SIGN influenced by: As noted by others, Ambrose Bierce (“Haita the Shepherd,” “An Inhabitant of Carcosa). There’s also a strong whiff of Poe (cf things like “The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Masque of the Red Death,” etc). And, pervading everything, we have the decadent/aesthetic atmosphere of the “Yellow ‘90s.”

Influence On:Quite a few. I’ll simply list some of the more notable ones. HPL, but more as a matter of names and allusion and incorporation. Karl Edward Wagner (see his short story “The River of Night’s Dreaming”). James Blish (another of HPL’s epistolary friends-they seem to be legion) produced his own version of the play in “More Light.”

HPL and Chambers: The fascinating thing is that HPL came to Chambers so late in his development as a writer, long after he had gone through his sedulous ape period (imitating Dunsany), long after he had assimilated Machen and Blackwood, long after he immersed himself in Poe, etc. His tropes and properties were firmly in place (cosmicism, the Necronomicon, allusive references to Al-Hazred, etc). Yet now he found himself reading an author who had employed a similar armory back in 1895, whose stories, in some ways, read like HPL’s earlier efforts (cf the Decadence-Aesthetical drenched “The Hound,” which also marks the first appearance of The Necronomicon).

Here’s a link to James Blish’s riff on THE KING IN YELLOW, “More Light”

https://books.google.com/books?id=Sxhiog7Y8EAC&lpg=PP1&ots=wxiDR_ElXM&dq=%22More%20Light%22%20James%20Blish&pg=PA84#v=onepage&q&f=false

Ajay @@@@@ 18: He mentions doing work for the Met. This is actually extremely plausible–one of my parents’ friends does tapestry weaving for the Cloisters. New York is a good place to practice ancient arts, and is likely to continue so through any number of regime changes.

Good point. It just came across as a kind of leap backwards (in the same way that having exiled noblemen and a Rightful King of America does). It reminds me slightly of some of the weirder bits of GK Chesterton’s future fiction, which have a similar leap-backwards approach; The Napoleon of Notting Hill has people fighting with halberd and pike in the streets of 1984 London. The Ball and the Cross has a running duel with swords between a Skye Catholic and an atheist.

More recently, Amanda Downum’s Dreams of Shreds and Tatters has a whole lot of Carcosa going on.

#29, thanks. I couldn’t make any blasted sense out of the Wagner story, even apart from my aversion to kink of uncertain consent. Thanks all, I always learn from these threads. And no, I have no interest in branding anyone’s skull.

Joseph Pulver has edited a couple of KIY themed anthologies, 2012’s A Season in Carcosa and, last year, a recent addition to the small-yet-ceaselessly-growing subgenre of all-female Mythos anthologies, Cassilda’s Song.

@29: I seem to have a large Karl Edward Wagner-shaped hole in my library but I’m working on getting that fixed. In a Lovecraftian vein I remember enjoying “Sticks”, which was based on a strange experience Lee Brown Coye had in an abandoned farmhouse.

@22:”And yes, we’ll definitely have to look at “The Yellow Wallpaper,” both because early weird fiction seems pretty unbalanced in the testosteronish direction, and because it’s the only one I was ever assigned in English class.”

Along those lines, there’s also the weird work of Mary Wilkins Freeman, which HPL quite liked:

“Horror material of authentic force may be found in the work of the New England realist Mary E. Wilkins; whose volume of short tales, The Wind in the Rose-Bush, contains a number of noteworthy achievements. In “The Shadows on the Wall” we are shewn with consummate skill the response of a staid New England household to uncanny tragedy; and the sourceless shadow of the poisoned brother well prepares us for the climactic moment when the shadow of the secret murderer, who has killed himself in a neighbouring city, suddenly appears beside it.”

Looking at her work would also shed light on HPL as a regional author. After all, one of the things that makes Lovecraft so distinctive is the way that he combines the local (his beloved New England) with the comic.

@22:”And yes, we’ll definitely have to look at “The Yellow Wallpaper,” both because early weird fiction seems pretty unbalanced in the testosteronish direction, and because it’s the only one I was ever assigned in English class.”

Along those lines, there’s also the weird work of Mary Wilkins Freeman, which HPL quite liked:

“Horror material of authentic force may be found in the work of the New England realist Mary E. Wilkins; whose volume of short tales, The Wind in the Rose-Bush, contains a number of noteworthy achievements. In “The Shadows on the Wall” we are shewn with consummate skill the response of a staid New England household to uncanny tragedy; and the sourceless shadow of the poisoned brother well prepares us for the climactic moment when the shadow of the secret murderer, who has killed himself in a neighbouring city, suddenly appears beside it.”

Looking at her work would also shed light on HPL as a regional author. After all, one of the things that makes Lovecraft so distinctive is the way that he combines the local (his beloved New England) with the cosmic*.

*typo corrected

To all: I heartily endorse the idea of a “Yellow Wallpaper” read! :)

@Rush-That-Speaks and @R.Emrys: There are *absolutely* multiple interpretations of this story. Seeing “Jane” as the otherwise unnamed narrator has a nice resonance to it : Jane and John. However, there are other J-named women in the story: Julia (Cousin Henry’s wife) and Jennie (the sister-in-law, who seemingly colludes with John in restricting the narrator’s actions under the “rest cure”). Not to get all professor-y up in here, but in my classes we discuss a couple of possibilities for unpacking the story

– As a chilling tale of mental illness (in “Danse Macabre,” Stephen King describes it as the tale of a woman slowly going crazy). In that case, we might see the narrator as completely unreliable, for which there is plenty of evidence (for example, her noticing the “smooch” on the wallpaper, which we finally realize is made by her endless creeping around the room – AFTER she describes the visual hallucination of seeing women creeping around the grounds outside). In that case, referring to herself in the third person at the end of the story or confusing Jennie/Julia’s name isn’t so unlikely – this is the same woman who just told her husband the key to the room was under a plantain leaf (a reference which, I have to admit, I have NEVER understood).

– As a tale of a woman suffering under a patriarchal societal and medical establishment. Google “Why I Wrote the Yellow Wallpaper” for a nice historical perspective on the story and an account of Gilman’s own disastrous experience with the “rest cure” (apparently this story helped raise awareness of how harmful this cure could actually be). The narrator in the story has just had a child, which has led some critics to talk about post-partum depression, which was not understood in the late 1800s. This was also the era in which women were being infamously diagnosed with “hysteria” by male relatives who wanted an excuse to control them (remember that both the narrator’s husband and brother are well-regarded doctors and that her husband is in charge of her treatment, which involves being forced to give up writing, reading, and essentially all “intellectual life.” He also infantilizes her and dismisses her concerns about her mental health.). @R.Emrys mentioned the concept of redemption and, if we do an archetypal reading, we might consider that the woman “behind the bars” of the wallpaper only comes out at night in the moonlight; the moon is an archetypically and mythologically feminine symbol. The narrator also sees other “creeping women” outside in the garden: the natural world being another archetypal female symbol. At the end, is the narrator “free” of the prison the men in her life has build about her?

– As a purely supernatural story. I have to admit that I’m not fond of this particular interpretation (possibly because of the *ABOMINATION* that was the film of the same title). I personally think seeing this purely as a ghost story is too reductive. To me, it’s more liminal than that – which makes it (to me, again) infinitely more disturbing. I personally like a combination of all of the above interpretations (reminding us that effective literature can’t easily be “put in boxes”)

Here I’ve come full-circle back to the idea of the unreliable narrator and “The Repairer of Reputations.” To me, Gilman, Chambers, and later Shirley Jackson (as in “The Haunting of Hill House” and “We Have Always Lived in the Castle”) have created the creepiest kind of unreliable narrator – simply because I think we CAN rely on *some* of what they say. The narrator in Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” is sometimes cited as the classic unreliable narrator, but I find them less compelling simply because we know from the very beginning they are utterly unreliable. (Their illness means they now hear many things in heaven and in hell? Come on.). :P Yet I believe that, in “The Yellow Wallpaper,” the narrator’s husband is *indeed* making her worse by enforcing the rest cure and forcing her to sleep in the “nursery” with that dreadful paper. I believe in at least of some the environment and world of “The Repairer of Reputations” because (at least to me) the entire story is otherwise just the narrator’s delusional rantings and therefore less effective as a narrative, especially in the context of the entire “King in Yellow” cycle. However, that moment with the safe/biscuit box is again chilling, bringing everything else under question. In a way, Chambers was WAY ahead of his time and anticipating the post-modern movement in which everything (including reality) can be seen as a personal construction.

Wow…sorry to “lessonate” so much! I’m on winter break from teaching right now and have some trouble turning off “professor mode” – just in case you couldn’t tell! ;)

@34:”I seem to have a large Karl Edward Wagner-shaped hole in my library but I’m working on getting that fixed. In a Lovecraftian vein I remember enjoying “Sticks”, which was based on a strange experience Lee Brown Coye had in an abandoned farmhouse.”

Wagner’s short fiction is pretty good. Besides the already mentioned “River of Night’s Dreaming” and “Sticks,” there’s also “Where the Summer Ends,” an interesting variation on Machen’s “Little People” mythos.

And here’s another writer who was influenced by Chambers’ KING IN YELLOW: Raymond Chandler. Here’s the relevant bit from his short story, “The King in Yellow”:

Leopardi lay squarely in the middle of the bed, a large smooth silent man, waxy and artificial in death. Even his mustache looked phony. His half-open eyes, sightless as marbles, looked as if they had never seen. He lay on his back, on the sheet, and the bedclothes were thrown over the foot of the bed.

The King wore yellow silk pajamas, the slip-on kind, with a turned collar. They were loose and thin. Over his breast they were dark with blood that had seeped into the silk as if into blotting-paper. There was a little blood on his bare brown neck.

Steve stared at him and said tonelessly: “The King in Yellow. I read a book with that title once.

Say, has anyone done a Philip Marlowe-KING IN YELLOW mash-up. Maybe Louis moved West to California with Constance, and they had some daughters (Cassilda and Camilla, , natch).And something happens( perhaps a variation on THE BIG SLEEP) that requires the services of Marlowe. Plus, there’s the added frisson that comes from knowing the fate that awaits the West Coast:

“We are now in communication with ten thousand men,” he muttered. “We can count on one hundred thousand within the first twenty-eight hours, and in forty-eight hours the State will rise en masse. The country follows the State, and the portion that will not, I mean California and the Northwest, might better never have been inhabited. I shall not send them the Yellow Sign.”

The blood rushed to my head, but I only answered, “A new broom sweeps clean.”

@jaimew: Plantain leaf is a folk remedy against rattlesnake bites and the bites of rabid animals; since it is one of the main preventatives for rabies (a usage which goes back to Pliny), it also has the reputation of curing more general madness. So the narrator saying that the key to the room is under a plantain leaf means that the key, metaphorically, is inaccessible without a cure: a cure either for her own madness, or for the poisonous supernatural influence which has attacked her and seeped into her like rabies, or for both. The key is also literally under a plantain leaf because the greater plantain is a common weed throughout North America and it landed there when she threw the thing out the window, but that’s the boring part. Note also that she can see the key and the (representation of the concept of a) cure outside, away from her, but cannot access them herself– the key willingly, but the plantain because she hasn’t been let down there in ages.

I’ve never seen a distinction between @jaimew‘s three interpretations– the narrator almost certainly has postpartum depression, as her author had; the ‘rest cure’ is actively deleterious and driven by a patronizing and paternal sexism; and there is this pervasive academic insistence that this story cannot or should not be supernatural that I have never understood. I put it down to the supernatural not being academically respectable. The thing is, it’s a better story if it’s a real ghost, because ghosts, hauntings, are the shadows of the past. If there is a ghost, if there was another woman imprisoned there who was also mad either for the same reason or for a different one, then that increases the weight of destructive patriarchy in the story by showing that the narrator and her situation are extensions of things that have been happening for an unspoken, unknown duration, for a very long time. It’s not just these men now who are perpetrating this, but the generations backward. It’s not just this individual narrator, but the cycle of how women are crushed societally by the men who claim to, and even do, love them. I think that mooring weight increases the story’s emotional impact significantly. I also think that the story is better structurally if you see it as containing a clever way of indicating a real haunting, and I think that it is far more likely, considering when the piece was written, that the author would have been considering a real ghost. But all that is of course arguable.

Mostly I look at the school of criticism that says the piece is non-supernatural and wonder why making it supernatural would be at all reductive, when seeing it that way doesn’t shut out any of the other interpretations, but multiplies them.

@38: Thankyou for the recommendation, I hope that KEW’s horror fiction will soon get the wider release it deserves.

I was always disappointed that Chandler didn’t go full cosmic horror in “The King in Yellow”. (I recall that “The Bronze Door” has a bit of Madness Takes Its Toll but in a (to me less-interesting) slick way.) I still like to imagine that Grayce is referring to the play rather than the collection in that line. Though Chandler-Lovecraft crossovers are common, I’m not aware of a full scale Chandler-Chambers crossover.

@Rush-That-Speaks: Thank you SO much for the “plaintain leaf” explanation; I’ll be sure to talk about that when I teach this story next semester (and give credit to you, of course!).

Like I said in my previous post, I personally like a liminal combination of “close readings” of “The Yellow Wallpaper,” which, to my mind, makes it far creepier. Listen, I’m a HUGE fan of supernatural literature – I’m pretty much the only horror expert in my department and have taught Poe, Stoker, Blackwood, Lovecraft, Poppy Z. Brite/Billy Martin, Caitlin R. Kiernan, Stephen King – and many more! :). I can’t speak for academic discourse in general, but I think I perhaps tend to shy away from a completely supernatural interpretation of Gilman’s story because I’ve seen far too many students do that as a way to “dismiss” it. Whether or not it’s a ghost story, it’s also deeply rooted in the reality of women’s oppression by various late 19th-century institutions. It’s not comfortable for many people (and I am NOT talking about ANYONE on this read!) to think about the fact that barely over 100 years ago in this country, a husband had the legal power to make his wife a virtual prisoner.

I don’t think we need to “explain away” the supernatural in literature, or find corporeal ways to frame it. However, I think we do (to expand this discussio) Lovecraft a disservice if we don’t think about how the modernist ethos helped shape his work, or if we don’t see reflexions of international tension in the “utopia(?)” of “The Repairer of Reputations.”

@41: Jaimew:” However, I think we do (to expand this discussio) Lovecraft a disservice if we don’t think about how the modernist ethos helped shape his work,”

Here’s some stuff from Alan Moore on Lovecraft and modernism:

Higgs: He didn’t like the Modernists at all in terms of writing and things like that —

Moore: He was conflicted. He was a closet Modernist himself. I mean, yeah, he hated Gertrude Stein, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce. He wrote a brilliantly funny and actually very well-written parody of “The Waste Land” called “Waste Paper.” But, you actually look at Lovecraft’s writing, and, much as he’s decrying all of the Modernists, much as he’s bigging-up his favorite 18th Century authors – people like Pope – actually Lovecraft is a modernist.

He’s using stream of consciousness techniques. He is using glossolalia more impenetrable than anything in Finnegan’s Wake. He is using techniques that… deliberately alienating the reader or confusing the reader. His descriptions tend to be along the lines of “here’s three things that C’thulhu doesn’t look like.” Or he’ll describe “The Colour out of Space” as only a color by analogy. So, what is it a sound? Is it a rough texture, or a smell? What? These are deliberate kind of techniques. They’re not flaws. They are techniques at alienating the reader – of putting the reader into an uncanny space where the language is no longer capable of describing the experience.

Higgs: For Horror, it was all the Gothic Horror sort of gone – it’s sort of Modern Horror…

Moore: That’s important. All Horror – or most Horror up to Lovecraft – had all been predicated on the Gothic tradition, which is a tradition where you have an enormous vertical weight in time that is bearing down upon a fragile present. A history of dark things in the past that are bleeding up to some terrifying denouement in the present day.

With Lovecraft, yes, there is an awful lot of talking about romantic antiquity and the past. But with Lovecraft I think that it’s a much more present horror of the future. He’s talking about that time when man will be able to organize all of his knowledge. And when that time comes the only question is whether we will embrace this new illuminating light. Or whether we will flee from it into the reassuring shadows of a new Dark Age. Which is very prescient given, say, current fundamentalism, which is a direct – a response to too much knowledge, too much information. Let’s take it all back to something that we’re sure of: God created the world in six days.

Yeah, in that way Lovecraft was sort of – yeah, he was really exploring all of the – he was a very… he is still a very contemporary writer.

[…]

I think that Lovecraft’s preoccupations were so forward-looking that… and his writing techniques were so unusual that you could, yeah, use Lovecraft as the starting point for a new kind of Modernist Horror

https://factsprovidence.wordpress.com/2015/11/05/alan-moore-interviewed-on-the-20th-century/

@trajan23: Once again, I’m in agreement with Alan Moore. I’m well aware of “Waste Paper” (although I *might* argue Moore’s claim that it’s “well-written!”). I maintain that works like “The Outsider” and “The Silver Key” completely embody the alienation of the modernist ethos (as I think I commented on the read of “The Silver Key”). I am constantly ticked-off at modernist scholars who know nothing about or refuse to acknowledge Lovecraft as a modernist artist (h3ll, he even had his own American version of the Bloomsbury circle!).

I love the layers of confusion in this story. We have the unreliable narrator who seems to be pretty evil. At the very least, he’s insane. We have the world he lives in which he views as utopia and we view as dystopia–but it’s not always clear how much of the dystopia is real and how much is his perception. On top of that, we have two layers of time, the author’s use of a false future mixed with our own perception of how the 20th century worked out.

So, for example, let’s just take a look at the Indians in the military.

As a 21st century reader, I find the reference to the “Indian question” so close to being told Jews aren’t being allowed to enter the US disturbing. For me, it’s a clear echo of the Nazis’ “Jewish question” and how that was resolved.

But, of course, that hadn’t happened yet. On the other hand, the factors that would lead to the Holocaust were also tied to the “Indian question” and to the mindset of someone (albeit fictional and probably insane) who thinks it’s a good thing Jews are being excluded.

A further problem at this point is that I don’t know the author viewed Jews. Did he favor their exclusion? Was he against it? How did he expect his audience to react to it? As a modern reader, this seems like one of the signs that the narrator is not a good person. When I try to figure out how it might have played in the writer’s own time, I’m not sure what it was supposed to be telling me.

But, getting back to Native Americans.

On one level, looking at the extreme hardships, cultural breakdown, and demoralization they suffered, the brief image we get doesn’t seem like a bad thing. We’re given a contrast between the ragged, demoralized scouts of a few years before and the ones of the narrator’s present who seem confident and whose native dress seems to speak of cultural pride and (more importantly) cultural revitalization.

Except, this is in a strictly military setting. Also, native dress, especially in fiction, can be used to underline the otherness of a group.

If Native Americans have been given a respected place in this society, that may be a good thing. If it’s a strict matter of caste–a person of this ethnic background can be accepted but only in certain jobs–that’s not such a good thing (although arguments could be made about the lesser of two evils and how this compares to some of the things happening at the end of the 19th century).

But, maybe it’s not a question of what their place is so much as what they’re doing? Was this social incorporation? Or was it more like hiring foreign mercenaries to control your own people?

Even in terms of the story, it’s hard to tell when we’re looking at victims of oppression in this society or tools of its oppression.

Toss in the added question of not knowing how much of what the narrator perceives is accurate. I just love the layers of unreliability in this story.

one final, alarming question that’s still bothering me days later. Plays are normally intended to be performed. Anyone who’s both appreciated Shakespeare on stage, and read him in the classroom, knows that the reading experience is a pale shadow of actually sitting in a darkened theater watching the acts unfold. So what happens to people who see The King in Yellow live?

And what effect does it have on those who act in it? Breaking a leg might be a mercy.

Waaaay late to the party here, but didn’t see an answer to this in any of the comments above, so–Read Charles Stross’ “The Annihilation Score” for an answer to that question, at least in one version of the Mythos. Not sure how well intelligible it will all be if you haven’t read the previous books in the Laundry Files series, but outstanding read if you have. Are those novels going to be included in this series?

Oh, cool! I’m a couple behind on that series and really need to catch up. Probably not going to cover full novels, but A Colder War will happen one of these weeks when neither of us is stuck in editing hell.

Its really clearly a dystopian fiction. It was supposed to be seen as dystopian. Dont assume the writer is a racist alright.

@10 (AeronaGreenjoy),

As half mine would have been after the eugenics-based immigration laws of the 1920s (they immigrated prior to WWI) and wer the same ones which later meant my brother-in-law’s father had no cousins survive WWII.

But, getting back to Native Americans. On one level, looking at the extreme hardships, cultural breakdown, and demoralization they suffered, the brief image we get doesn’t seem like a bad thing. We’re given a contrast between the ragged, demoralized scouts of a few years before and the ones of the narrator’s present who seem confident and whose native dress seems to speak of cultural pride and (more importantly) cultural revitalization. Except, this is in a strictly military setting. Also, native dress, especially in fiction, can be used to underline the otherness of a group.

I suspect that what he’s doing here is extrapolating from how other imperial powers treated their subjects. The rebellious Scottish Highlanders were crushed – and regiments of kilted infantry raised from the Highlands. The Sikhs tried to invade India and were defeated, and the Punjab annexed by India – and the Indian Army acquired Sikh regiments. It’s something that empires have done since the Romans, and what puzzles me is that as far as I know the US army never considered it. It’s not like it had a problem with racially segregated regiments. Why didn’t some inventive colonel suggest raising the Twelfth (Sioux) Regiment, US Cavalry?

@49,

Possibly for the same reason Hitler didn’t raise Jewish regiments: Manifest Destiny wasn’t about conquering the Native Americans; it was about displacing orexterminating them.