Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

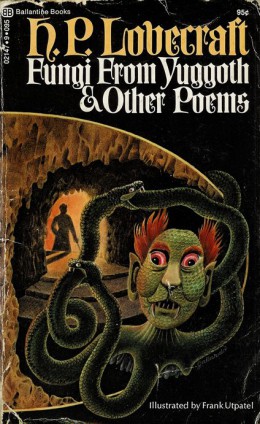

Today we’re looking at the first 12 sonnets in the “Fungi From Yuggoth” sonnet cycle, all written over the 1929-30 winter break (December 27 to January 4, and don’t you feel unproductive now?). They were published individually in various magazines over the next few years, and first appeared together in Arkham House’s Beyond the Wall of Sleep collection in 1943.

Spoilers ahead!

The daemon said that he would take me home

To the pale, shadowy land I half recalled

As a high place of stair and terrace, walled

With marble balustrades that sky-winds comb,

While miles below a maze of dome on dome

And tower on tower beside a sea lies sprawled.

Once more, he told me, I would stand enthralled

On those old heights, and hear the far-off foam.

Summary: Any summary is, of necessity, an exercise in interpretation. This is more the case with a poem than with straightforward prose, and even more the case with a sonnet cycle that may or may not be intended as a continuous story. (In fact, Anne interprets several of the sonnets as stand-alones, while Ruthanna’s convinced that they form an overarching narrative.) Be warned—and go ahead and read the original. Several times, if you end up as confused as your hosts.

- The Book: Unnamed narrator finds an ancient and dusty bookshop near the quays. Rotting books are piled floor to ceiling like twisted trees, elder lore at little cost. Charmed, narrator enters and takes up a random tome of monstrous secrets. He looks for the seller, but hears only a disembodied laugh.

- Pursuit: Narrator takes the book and hides it under his coat, hurrying through ancient harbor lanes, longing for a glimpse of clean blue sky. No one saw him take the book, but laughter echoes in his head. The buildings around him grow maddeningly alike, and far behind he hears padding feet.

- The Key: Narrator makes it home somehow and locks himself in. The book he’s taken tells a hidden way across the void and into undimensioned worlds. At last the key to dream worlds beyond earth’s “precisions” is his, but as he sits mumbling, there’s a fumbling at his attic window.

- Recognition: The narrator sees again (in a vision during his work with the book?) a scene he saw once as a child in a grove of oaks. But now he realizes he’s on the gray world of Yuggoth. On an altar carved with the sign of the Nameless One is a body. The things that feast on the sacrifice are not men; worse, the body shrieks at narrator, and he realizes too late that he himself is the sacrifice.

- Homecoming: A daemon (summoned to bring these visions?) promises narrator he’ll take him home to a tower above a foaming sea. They sweep through sunset’s fiery gate, past fearful gods, into a black gulf haunted by sea sounds. This, the daemon mocks, was narrator’s home when he had sight.

- The Lamp: Explorers find a lamp in caves carved with warning hieroglyphs. It bears symbols hinting at strange sin and contains a trace of oil. Back in camp they light the oil and in its blaze see vast shapes that sear their lives with awe. (Is this the previous narrator and his daemon? The narrator and someone else, earlier? Later? Entirely unrelated to the rest of the cycle? My, what excellent questions you have.)

- Zaman’s Hill: A great hill hangs over an old town near Aylesbury. People shun it because of tales of mangled animals and lost boys. One day the mailman finds the village utterly gone. People tell him he’s mad to claim he saw the great hill’s gluttonous eyes and wide-open jaws. (Narrator remembering something he heard about once? Narrator traveling Lovecraft County trying to learn more cosmic secrets? POV switch as we get hints of what the fungi are up to? Excellent questions.)

- The Port: Narrator walks from Arkham to the cliffs above Innsmouth. Far out at sea he sees a retreating sail, bleached with many years. It strikes him as evil, so he doesn’t hail it. As night falls, he looks down at the distant town and sees that its streets are gloomy as a tomb. (Same questions as above—still good questions.)

- The Courtyard: Narrator goes again to an ancient town where mongrel throngs chant to strange gods [RE: pretty darn sure this is still Innsmouth.]. He passes staring rotted houses and passes into a black courtyard “where the man would be.” He curses as the surrounding windows burst into light, for through them he sees dancing men, the revels of corpses none of which have heads or hands. (Questions. Yup. We have them.)

- The Pigeon-Flyers: People take narrator slumming in a neighborhood of evil throngs and blazing fires. (Still in Innsmouth?) To the sound of hidden drums, pigeons fly up into the sky. Narrator perceives that the pigeons fly Outside and bring back things from a dark planet’s crypts. His friends laugh until they see what one bird carries in its beak. [RE: I think this is a new definition of “pigeon” not used before or since. Winged things that fly to Yuggoth? Hm.]

- The Well: Farmer Seth Atwood digs a deep well by his door with young Eb. The neighbors laugh and hope he’ll come back to his senses. Eb ends up in a madhouse, while Seth bricks up the well and kills himself. The neighbors investigate the well. Iron handholds lead down into blackness bottomless as far as their sounding lines can tell. So they brick the well back up. (See above re questions still totally unresolved.)

- The Howler: Narrator has been told not to take the path that leads past the cottage of a witch executed long before. He takes the path anyway, to find a cottage that looks strangely new. Faint howls emanate from a room upstairs, and a sunset ray briefly illuminates the howler within. Narrator flees when he glimpses the four-pawed thing with a human face. (And we finish up with… questions.)

What’s Cyclopean: The need for scansion keeps the sesquipedalian vocabulary in check, but Lovecraft still manages some linguistic oddities: for example, rhyming “quays” with “seas” and “congeries.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Where Innsmouth is mentioned, there must also be warnings against “mongrels.”

Mythos Making: The cycle might well have been re-titled, “Here’s What I’ll Be Writing for the Next Three Years.” The first third includes early versions of Outer Ones, Deep Ones, the astral travel of “Witch House” and “Haunter,” and the shop from “The Book.” Also call-backs to the previously appearing Whatelies and nightgaunts.

Libronomicon: The first three sonnets cover the acquisition of a creepy book from a creepy store—a book that contains the lore needed for the journeys described elsewhere in the cycle. [RE: my interpretation, at least.]

Madness Takes Its Toll: A village disappears. Mailman claims the hill ate it. Mailman gets called “mad,” but no one has a better explanation. Maybe we should ask the mailman how these poems are really supposed to fit together.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

“Wait,” I said. “They’re not all the same rhyme scheme! Can you do that?” “Mike Ford did,” said my wife. “Go back and look at ‘Windows on an Empty Throne.’” And indeed, Ford also switched cheerfully between Petrarchan and Shakespearian forms—he just did it so smoothly and transparently that I never noticed. (Either that or I read Ford less critically than I do Lovecraft, a distinct possibility.) In any case, Lovecraft’s command of the sonnet is good enough that he can get away with a cycle, and flawed enough to attract attention to structural details.

But the content is more intriguing—the “Fungi” poems not only benefit from rereading several times, but I think benefit particularly from reading, as we’re doing here, immediately after immersion in the rest of Lovecraft’s oeuvre. They’re deeply embedded in those stories, both the preceding ones and those following. Although the poems were first published separately, and some people [ETA: like Anne, it turns out] question whether they are really meant to be read as a unit, they seem to me not only to create an arc in themselves, but to fit very clearly in the story-writing timeline. Lovecraft penned them just after “Dunwich Horror,” and just before the remarkable run of masterpieces that starts with “Whisperer in Darkness” and stretches to the end of his career.

If I had to take a wild guess, “Fungi” is the point where Lovecraft admitted to himself that he wasn’t just repeating references to Azathoth and nightgaunts and Kingsport and Arkham, but was creating a Mythos. “Whisperer” is where his stories start to take worldbuilding really seriously, where the connections between species and magical techniques and locations become overt and consistent. There are hints earlier, and light continuity, but from this point onward only “The Book” doesn’t tie tightly to his preceding work.

“Fungi” plays with these connections, and lays out sketches for the central conceits of the next several years. All change somewhat between poem and story—but here are Outer Ones kidnapping whole towns and bringing them Underhill, Innsmouth flashing messages to unspecified monsters, astral travel in witch-haunted houses, and of course Yuggoth itself in glimpses of wonder and fear. Seen in this context of Mythosian rehearsal, the dreadful tome and the summoned daemon create a framing sequence—that allows visions of tales to come.

There’s more going on than iambic story notes, though. There are only hints in the first third (I’m trying to be good), but

The daemon said that he would take me home

To the pale, shadowy land I half recalled

Yuggoth is alien and terrifying—and simultaneously an archetypal longed-for homeland, of a piece with Randolph Carter’s sunset city. Lovecraft to the core, and a very personal take on knowledge’s mixed temptation and repulsion—the narrator’s visions disturb him, but he yearns for their fulfillment.

Mind you, narrator yearns for Yuggoth even though strange beasts ate his body the last time he was there. I guess home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.

Anne’s Commentary

Like many a tome of forbidden lore, the sonnet has endured from its development in 13th century Italy even unto the present day. Endured, indeed, and prospered, and evolved. Despite a certain modernist disdain, there probably aren’t many aspiring poets who haven’t given the form a try. Its structure is sturdily compact, neither so short that it produces mere aphorism nor so long that the poet is tempted toward rambling. The formal break between the first eight lines (the octave) and the last six lines (the sestet) cries out for statement and counter-statement, for mood switches, for mind changes, for set-up and crisis: the turn or volta which is a prime feature of the sonnet.

It’s not surprising that Lovecraft was attracted to the sonnet. It is surprising (and impressive) to realize that he wrote most of the poems in the Fungi from Yuggoth sequence in little more than a week over the 1929-1930 holiday season. In addition to exercising himself in the venerable form, he appears to have made a conscious effort to avoid the floweriness of some earlier poems, replacing it with straightforward diction.

Lovecraft uses both major forms of the sonnet, the Italian or Petrarchan and the English or Shakespearian. Both adhere to the octave-sestet structure but the basic rhyme schemes differ. The Italian sonnet typically uses the abbaabba scheme in the octave, with variations on c-d or c-d-e in the sestet. As English is more “rhyme-poor” than Italian, the English sonnet typically uses an ababcdcd octave and an efefgg sestet. The rhyming couplet (gg) that closes so many English sonnets is rare in the Italian sonnet. Lovecraft likes the rhyming couplet so much that he uses it in all twelve poems we’re considering today, even the Italianate ones. Four poems (II, III, VI and VII) are standard English sonnets. Six (I, IV, V, VIII, IX and XII) are more or less standard Italian sonnets. Two (X and XI) appear to be Italian-English hybrids, with X (The Pigeon-Flyers) the most idiosyncratic of this group (ababcddc effegg.)

Lovecraft’s scansion is flexible, no strict plodding of iambs (unstressed/stressed syllable pairs) through the five feet of every line. Both meter and rhyme scheme bend to what he wants to say and serve that direct diction he claimed to be trying for.

Overall, some pretty good sonnets here! Especially since they’re also weird and eerie as hell, a rare thing in sonnets and poetry in general. Lovecraft’s usual (thematic) suspects are well-represented. We’ve got tomes and tottering semi-animate buildings and pursuit by things that don’t bear thinking of. We’ve got voids and extra-dimensional worlds. We’ve got sunset spires beyond the mundane waking world. Ancient alien invasions and human sacrifices. Maddening artifacts. Eldritch New England, including Arkham and Innsmouth and the Dunwich area (implied by the near vicinity of Aylesbury.) Unfathomable depths. Howling semi-bestial remnants of executed witches. Evil mongrel throngs in decaying cities. The first three sonnets are obviously connected. The rest can stand alone—they’re like captured fragments of dream polished into suggestive little gems of micro-story.

My favorites are, in fact, the most straightforward of the sonnets, each of which could have been expanded into full-length shorts or even something on the novelette-novella-novel spectrum. “The Lamp,” cousin to “The Nameless City” and other archaeological horrors. “Zaman’s Hill” with that wonderful image of the hungry earth (or what poses as earth.) “The Courtyard,” where “a man” is to be met—the same man who’s absconded with all the dancers’ heads and hands? “The Well,” one of those homely tales that tear the sleepily bovine veil from rural life. “The Howler,” which may look forward to Keziah Mason and Brown Jenkins. And, most unsettling of all to us urban bird watchers and a tiny masterpiece of xenophobic paranoia, “The Pigeon-Flyers.”

Oh, and here’s my favorite set of rhymes, from “The Key”:

At last the key was mine to those vague visions

Of sunset spires and twilight woods that brood

Dim in the gulfs beyond this earth’s precisions,

Lurking as memories of infinitude.

Earth’s precisions! Infinitude! Nice little jolts out of the expected, which is the sort of jolting poetry ought to deliver.

Next week, we continue with sonnets XIII-XXIV of the “Fungi From Yuggoth” cycle. Will they answer our questions? No. Will they feature elder things? Very likely.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint in Spring 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.