“Return to Tomorrow”

Written by John Kingsbridge

Directed by Ralph Senensky

Season 2, Episode 22

Production episode 60351

Original air date: February 9, 1968

Stardate: 4768.3

Captain’s log. The Enterprise has picked up some kind of reading. Sulu has traced it to a planet and they head there, with Spock reporting that it used to be Class-M until the atmosphere was ripped away in a cataclysm. When they achieve orbit, the disembodied voice of Sargon is heard by everyone—he directed the ship to the planet with his thoughts, and is now speaking to everyone telepathically. He also says that he’s as dead as the planet, and he wants Kirk to rescue him from oblivion. Spock does detect energy readings deep beneath the surface, inside a chamber that is suitable for humanoid life support. Kirk beams down along with Spock, McCoy, and Dr. Anne Mulhall of astrosciences. Kirk doesn’t intend initially to take Spock or Mulhall, but Sargon makes it clear that he wants them both there. He also operates the transporter himself, and refuses to transport the two security guards.

Spock reports that the chamber was constructed around the same time the atmosphere was ripped away. The landing party is greeted by what looks like a giant glowing ping-pong ball—it’s a receptacle that contains Sargon’s essence. His people colonized the galaxy long ago, and later faced an ultimate crisis that wiped out the entire planet—their minds became so powerful they thought they were gods. Only a few survived as energy beings.

Sargon possesses Kirk, and he’s overwhelmed by the physical sensations that he hasn’t felt in half a million years. McCoy is not thrilled with this, especially since Kirk’s heart rate and body temperature are spiking. Kirk’s own mind is in Sargon’s receptacle, but his mind doesn’t have sufficient energy to communicate.

Sargon brings the landing party to another chamber, which has ten more receptacles—the eleven strongest minds were preserved even as the planet was destroyed. But after half a million years, only three survive—besides Sargon, there’s Thalassa (Sargon’s wife) and Henoch (who was on the other side). The plan is for the three of them to borrow Kirk’s, Mulhall’s, and Spock’s bodies temporarily to construct mechanical bodies to transfer their consciousnesses into. They can’t just give instructions to Enterprise engineers, their methods are far too sophisticated.

Kirk’s body is being overworked by Sargon’s possession, and so Sargon exchanges again. Kirk briefly touched minds with him, so he knows the plan, too. Sargon allows them to discuss it—and if they refuse, Sargon will allow them to leave if they wish.

Spock and Mulhall are cool with it, as is Kirk, but McCoy and Scotty are reluctant—McCoy is particularly dubious about the fact that they want the captain and second-in-command to be possessed. And McCoy also wants to know why Kirk wants to do this.

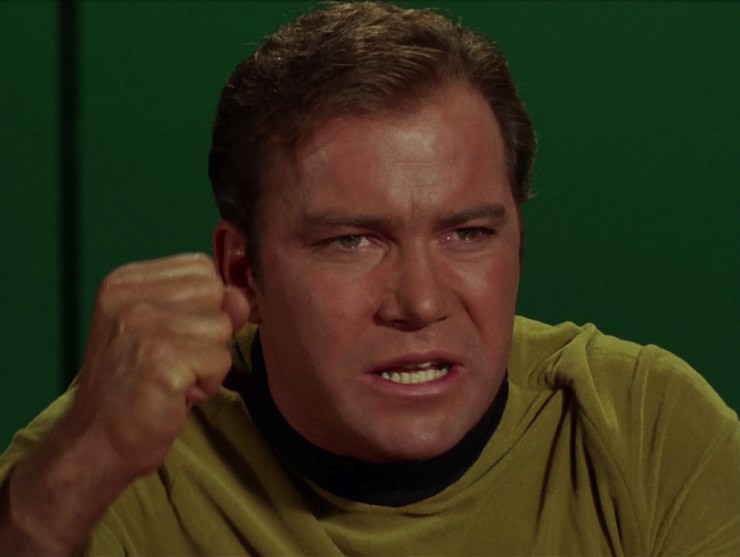

Kirk gives a lengthy and passionate speech, insisting that he won’t order everyone to go along with it, even though he could, but he also believes that the potential rewards are as great as the risks—and that risk is their business.

McCoy and Scotty are moved by the speech and agree to go along. Scotty beams the three receptacles up and the minds of the three survivors are transferred. McCoy tasks Chapel with keeping an eye on their metabolic rate.

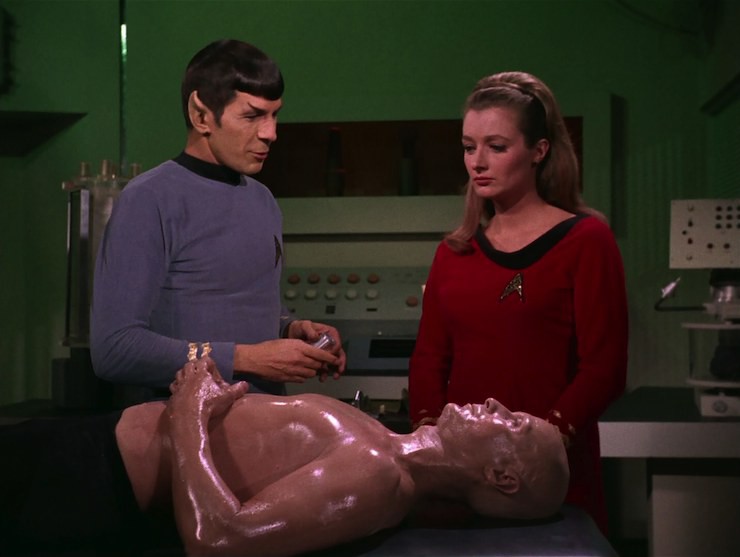

Henoch is thrilled to see a hot chick (Chapel) upon awakening, while Sargon and Thalassa are even more thrilled to be able to touch each other again. Both Kirk’s and Mulhall’s bodies are having trouble adjusting to the higher metabolism, but Spock’s body is more accustomed to it. Sargon asks Henoch to synthesize a metabolic reducer, which he does, with Chapel’s help. Henoch creates three hypos, one each for Sargon, Thalassa, and Henoch, but Sargon’s is different—which Chapel notices, but Henoch uses telepathy to brainwash Chapel. He wishes to keep Spock’s body, so Sargon (and Kirk) must die.

Sargon, Thalassa, and Henoch get to work constructing the mechanical bodies, though the former two are distracted by nostalgia for when they were alive and corporeal. Chapel is also acting a bit weird, as Henoch’s brainwashing isn’t as perfect as it might be.

But Henoch’s also working on Thalassa, trying to convince her that they should keep the bodies they’re in, which can actually feel, as opposed to the mechanical unfeeling ones they’re constructing. Thalassa goes to Sargon—only to find that he’s feeling ill. She tries to convince Sargon of what Henoch said, insisting that their minds in robot bodies can’t have mad passionate nookie-nookie—but then Sargon collapses. McCoy and Chapel arrive and he declares Kirk to be dead.

McCoy brings Kirk’s body to sickbay and is able to revive the bodily functions, but they have no means of transferring Kirk’s consciousness out of Sargon’s receptacle.

Henoch finishes Thalassa’s robot body, but she refuses to put her mind there. She goes to McCoy and offers to save Kirk in exchange for letting Thalassa keep Mulhall’s body. McCoy makes it clear that he will not peddle flesh. Angry, Thalassa starts torturing McCoy—and then she realizes what she’s doing and stops. And only then does Sargon’s voice sound in the sickbay. Sargon has placed himself inside the ship itself. He enacts a plan with Thalassa and Chapel, kicking McCoy out of sickbay. When he finally is let back in, Kirk is alive and well, and Mulhall is back in her own body as well. Sargon and Thalassa are now both together inside the ship, and the three receptacles have been destroyed. McCoy is devastated, as Spock’s consciousness was in one of them, but Kirk’s only reply is to have McCoy prepare the deadliest Vulcan poison he can concoct.

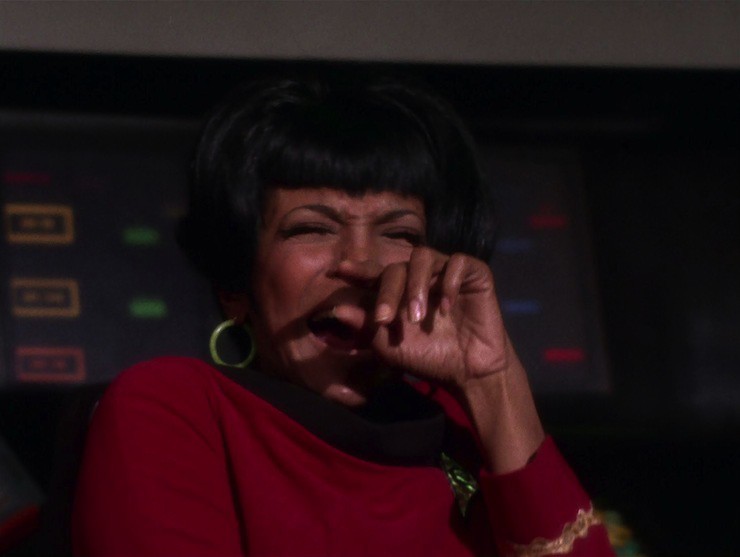

They arrive on the bridge—where Henoch is torturing Uhura and threatening to do the same to Sulu. McCoy tries to inject Spock, but Henoch stops him. He orders Chapel to give the poison to McCoy—but she sticks it in Spock’s arm instead.

Spock collapses, and Henoch abandons Spock’s body, fading into oblivion. But Sargon fooled McCoy into thinking he’d made a poison when, in fact, he just made something that would render a Vulcan unconscious. But Henoch believed it would kill him, because he read it in McCoy’s thoughts, so he fled. Spock’s consciousness, meanwhile, was in Chapel, which is how she was able to resist Henoch’s mind control, and is transferred back to Spock’s body.

Kirk and Mulhall give Sargon and Thalassa one last smooch before they fade into oblivion together.

Can’t we just reverse the polarity? Scotty is dismissive of the robot bodies, insisting that there be gears and pulleys—which honestly sounds hilariously primitive now, much less by the standards of the billions-of-years-advanced aliens…

Fascinating. Leonard Nimoy gets to laugh and smile and giggle and sneer and just generally be as not-Spock as it’s possible to be while Henoch possesses him.

I’m a doctor not an escalator. McCoy is against the plan from jump because of the physical consequences to the crew’s bodies as well as the other attendant risks, and his refusal to go along with Thalassa’s rather awful plan is a crowning moment of awesome matched only by his standing up to Khan.

Ahead warp one, aye. Sulu’s back! George Takei finally finished filming The Green Berets and is back to piloting the ship, though he really only gets two scenes.

Hailing frequencies open. Uhura gets to scream rather loudly when Henoch tortures her for defiance, and it’s a scream that makes it clear how much pain she’s in. (Honestly, Nichelle Nichols does a lot better than William Shatner or Diana Muldaur, who mostly just look like they have indigestion when Henoch goes after them a few minutes later.)

I cannot change the laws of physics! Scotty gets to play skeptic for the whole episode—he’s dubious about transporting through so much solid rock to get to the underground chamber, he’s dubious about the plan, he’s dubious about the robot bodies.

Go put on a red shirt. Two security guards are supposed to beam down with the landing party, but Sargon doesn’t transport them. I guess he didn’t need any dead bodies…

No sex, please, we’re Starfleet. Sargon and Thalassa are all over each other as soon as they’re corporeal again. Meanwhile, Chapel gets her long-standing wish of having Spock inside her. (Cough.)

Channel open. “I’m surprised the Vulcans never conquered your race.”

“Vulcans worship peace above all, Henoch.”

“Of course, Doctor, as do we.”

Henoch grooving on his awesome new bod, McCoy schooling him in Vulcan history, and Henoch providing a totally unconvincing rejoinder.

Welcome aboard. We’ve got the first of three Trek roles for Diana Muldaur as Mulhall (and as Thalassa possessing Mulhall). Muldaur will return in the third season’s “Is There in Truth No Beauty?” as Miranda Jones, and in the second season of TNG as Katherine Pulaski. (Amusingly, all three of Muldaur’s Trek roles are characters with doctorates.)

Plus, we’ve got both William Shatner and James Doohan doubling as Sargon, the former while possessing Kirk, the latter as Sargon’s disembodied voice, Leonard Nimoy doubling as Henoch possessing Spock, and other recurring regulars George Takei, Nichelle Nichols, and Majel Barrett.

Trivial matters: The episode received an uncredited rewrite by Gene Roddenberry, which led John Dugan to use the “John Kingsbridge” pseudonym. The specific rewrite that led to the pseudonym was the change to the ending, that Sargon and Thalassa were consigned to oblivion. A devout Catholic, Dugan wanted the pair of them to continue floating disembodied together in the universe, and he felt strongly enough about it to remove his real name from the script.

The script provides the very unsubtle name of the planet as “Arret,” which is “Terra” (an alternate name for Earth) spelled backwards. The name is never spoken aloud.

The 45th issue of DC’s first monthly Star Trek comic established that the supercomputer Vaal from “The Apple” was actually built by Sargon’s people. Sargon’s people were also referenced in Greg Cox’s The Q-Continuum trilogy and Christopher L. Bennett’s Department of Temporal Investigations novel Watching the Clock.

Kirk mentions the “first Apollo mission” that went to the moon, which accurately predicted that eventually NASA’s Apollo program would be successful and reach the moon, though it was not the first, but rather the eleventh Apollo mission that would do so a year and a half after this episode aired.

Your humble rewatcher taught a writing workshop for tie-in writing in 2004. One of the exercises I had the class do was to take the famous “risk is our business” speech Kirk delivers in the briefing room and rewrite it for one of the other Trek captains. It was meant as an exercise in doing different character voices.

To boldly go. “Risk is our business!” I always loved this episode as a kid, and I still enjoy it as an adult, though I can see its flaws much more so now.

As a kid I enjoyed the fun of watching Shatner and Nimoy play different people, I enjoyed watching McCoy stand up for his friends (“I will not peddle flesh” remains one of McCoy’s four or five best moments), and I enjoyed the whole concept of the minds in giant ping-pong balls.

As an adult, I see a lot more. The first two things I listed are still the main appeal here. DeForest Kelley is magnificent here, and his skepticism is well stated, sensible, and, as we see, totally justified. (Having said that, you also buy that he was moved by Kirk’s speech.) Shatner is far more focused and stentorian as Sargon, which makes the histrionics of the “risk is our business” speech that much more annoying. It’s in that speech in particular that Shatner’s reputation for overacting really started to grow its roots. Meanwhile, Nimoy is delightfully evil as Henoch, though the downside of that is that there’s no real surprise that Henoch turns out to be a bastard. That’s due in part to the episode running out of time for it. So much time is spent in the early going on drawn-out mystery and pointless misdirection (Sargon declaring that they must have their bodies in order to make the commercial break more dramatic, with him not explaining that they’re just borrowing until after the ads are done), that they have to rush through the actual plot.

Another problem is that they felt the need to drag in a woman we’ve never seen before to be the receptacle for Thalassa for no good reason, though there were plenty of bad ones. Honestly, this should have been a vehicle for Uhura, as the most prominent woman in the cast, but I’m sure that NBC would have had a conniption at the notion of an interracial kiss, something they would eventually try the next season, and that only got through barely and because Uhura and Kirk were forced to kiss (we’ll get into that in more depth when we slog through “Plato’s Stepchildren”). Here, Sargon and Thalassa going all kissy-face was necessary to the plot—so let’s cast a white woman we’ve never seen before! (To the script’s credit, Mulhall’s obscurity was used as a plot point when Thalassa tries to talk McCoy into letting her keep Mulhall’s body.) But Muldaur doesn’t really have enough time to make Mulhall into a person, and she doesn’t do enough to distinguish Mulhall from Thalassa, which takes the wind out of the sails of the plot.

I hadn’t realized how many times second-season Trek dipped into the well of aliens achieving human form and being overwhelmed by the sensory impressions, but unlike in “Catspaw” and “By Any Other Name,” it works well here, because Sargon, Thalassa, and Henoch have had humanoid forms in the past, but have been denied those feelings for half a million years, so of course it would be overwhelming, and lead both Henoch and Thalassa down the garden path of murder.

It also feels like far too many options were never brought up or explored. What about cloned bodies? Heck, how come these all-powerful super-scientific beings couldn’t manage to make a robot body that could feel? Why destroy the receptacles? (Besides, there were eight more intact ones down on the planet…) If they’re so telepathically powerful, why didn’t Henoch just take over from jump? And if Sargon was so much more powerful than Henoch that the latter had to be subtle, how did Sargon not know (after hanging out with his disembodied self for half a million years) that Henoch would betray them? I mean, I figured it out after he said all of three sentences…

Still, this is fun as an acting exercise for Shatner and Nimoy and for McCoy’s general awesomeness.

Warp factor rating: 6

Next week: “Patterns of Force”

Keith R.A. DeCandido feels real loose like a long-necked goose.

This episode is notable as the first of Star Trek‘s three attempts to explain the abundance of humanoid aliens in the universe, the others being the Preservers in “The Paradise Syndrome” (though that’s a belated attempt to explain Earth-parallel cultures specifically, and one that doesn’t really work for most of the previous Earth parallels we’ve seen anyway) and the First Humanoids from TNG’s “The Chase” (which everyone confuses with the Preservers even though they’re completely unlike each other in every other respect). Mercifully, “Return to Tomorrow” backs away from the annoying sci-fi trope of humanity being seeded on Earth by aliens, with Mulhall pointing out correctly that the scientific evidence overwhelmingly affirms that humans evolved on Earth. But the prospect that they’re the ancestors of Vulcans is left open.

As I probably remarked in my comments on Keith’s review of “The Chase,” my preferred breakdown is that the First Humanoids are the original source of all humanoid life, the Arretians are the source of Vulcanoids and various near-human species like Betazoids, Deltans, Fabrini, and Bajorans, and the Preservers just explain some duplicate cultures (perhaps including the “Bread and Circus” Romans, and maybe the Talarians from TNG’s “Suddenly Human,” who strike me as a possible Klingon offshoot — really, why should humans be the only ones they transplant?). I also posited in Watching the Clock that the Arretians were two species that shared a culture for a long time before turning on each other, with Henoch’s race being the ancestors of Vulcanoids and Sargon and Thalassa’s race being the ancestors of the near-humans.

I doubt that Muldaur’s casting was strictly about avoiding an interracial romance. TV of the ’50s through the ’70s was strongly guest-star-driven, with stories often written to center on the guest characters and have the regulars in a supporting role. Note that TOS’s end credits tended to bill the main guest stars above Doohan, Nichols, Takei, and Koenig. The show had become more centered on Kirk and Spock by this point, but it would still have probably been considered preferable to include at least one major guest star role to feature in the story, rather than keeping it strictly limited to the regulars. Diana Muldaur was a pretty well-known actress by this point, having established herself in The Secret Storm, Dr. Kildare, and assorted episodic guest roles, so she wouldn’t have been just an afterthought.

As for Shatner’s “overacting” in the big speech, what strikes me, on the contrary, is how understated and conversational he is at the start of it. He begins very naturalistically and then gets bigger as he grows more impassioned. I think it’s a very good performance. The parts of his performance I found excessive were when Sargon took him over, like in that last photo.

And of course credit has to be given to composer George Duning, who does a fantastic job underscoring Kirk’s speech and a good job with the rest of the episode. It’s the last full original score of the season, though we’ll have a few minutes of Nazi marches from Duning in “Patterns of Force” and a bit of “The Star-Spangled Banner” arranged by Fred Steiner in “The Omega Glory.”

Does anyone have a theory what the episode title means? I’ve never quite gotten it. “Return to Tomorrow” sounds like it should be the title of a time-travel story. Is it Sargon and the others who are returning to their own tomorrow, i.e. coming back hundreds of millennia after their time? If that’s it, it’s kind of labored. Or is it “tomorrow” in the sense of our evolutionary future, a civilization like us but far more advanced, having reached the ultimate crisis that makes our nuclear arms race look like a pillow fight? (By the way, the DC storyline that credited the Arretians with building Vaal also mistakenly assumed that their final war was a nuclear war, disregarding the clear dialogue from the episode.)

I wish they left ‘tomorrow’ out of the title. I always confuse this with Tomorrow is Yesterday. Had the series gone another season, I wonder if they’d gone to that well again and try to confuse me further — Yesterday’s Tomorrow is Today.

The part where McCoy declares Kirk/Sargon “dead”, and then in the very next scene he’s actually not dead (of course) reminds me of Kent Brockman’s report when Mr. Burns was shot: “He was taken to a hospital where he was pronounced dead. He was then taken to a better hospital where his condition was upgraded to alive.”

Here’s a link to Ralph Senensky’s blog entry about directing this episode:

senensky.com/return-to-tomorrow

I too am confused about the title, so much that it never rings any bells when I see it mentioned. No connection at all.

I like the first half of this episode, before they start the transfer, and of course McCoy is great here. Both his objections to Kirk’s plan and his scene with Thalassa were a great character show. But I don’t like the ending, all this musical chairs game with different bodies got boring and pointless really quick.

@1/ChristopherLBennett Agree about Kirk’s speech. I actually liked how it was done.

(But then, from my point of view, the worst case of overacting in entire series is Nimoy in Naked Time which is a scene considered great by everyone, so what do I know…)

The line that cracked me up today while rewatching is Sargon complimenting McCoy and Spock on keeping Kirk’s body in good state. Somehow never noticed it before.

@4/Darr: When Sargon says “I compliment you both” on the condition of Kirk’s body, he means Kirk and McCoy, not Spock and McCoy.

My bad :) Guess I just read it as Sargon talking to those present, Kirk being in the sphere and all.

Diana Muldaur really has the most beautiful eyes.

@6/Darr: The line was, “Your captain has an excellent body, Doctor McCoy. I compliment you both on the condition in which you maintained it.” So it’s “both” as in “both individuals mentioned in the previous sentence.”

At the end when Sargon tells everyone that he realizes that it’s too dangerous for the two of them to coexist with the Federation (or anyone else) I didn’t think anything of it the first few times I saw the episode, but when I got older and read more Star Trek novels I got to thinking, wasn’t it a bit irresponsible of Sargon to even try? After all, they destroyed themselves as a race and while it sounds noble to try to teach the rest of the galaxy not to make the mistakes they did, it’s kind of like the Prime Directive in reverse, where it is the beings on the planet that presents the danger of being the contamination rather than the ones contaminated..

And something that was never addressed: Since Henoch finished Thalassa’s robot body, that implies it was functional. So what happened to that robot after the episode? Did they just disassemble it and recycle the parts? Or did a family member somewhere between Arik and Noonien Soong somehow obtain it and study it?

And for that matter, speaking of robots/androids, could there have been some connection between Exo III (“What Are Little Girls Made Of?”) and Sargon’s people? That was pretty sophisticated android equipment, and sometimes the androids it made were very hard to distinguish from humans. I’m wondering if they could have inhabited an android like that without losing the ability to feel.

@9/richf: I think the implication of “What Are Little Girls Made Of?” was that android Korby had lost the ability to feel, even if he believed he retained some version of it.

Regarding the above quote from the episode – it is, simply, badly stated. Apollo 1 was never intended to reach the moon, even Apollo 8 was just for lunar orbit. There’s a lot of steps involved in getting to the moon, and I suspect this line was just misstated and would have been better as “Do you wish that the Apollo missions had never reached the moon” or words to that effect – I don’t think they meant to suggest a specific mission had done it. (After all, by the time this episode aired in February 1968, Apollo 1 was more than a year ago, and Apollo 5 had recently launched.)

MeredithP: Indeed…..

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

Maybe the future will see another space program called “Apollo”? Either a new Apollo project returning to the moon, or something entirely different which just shares the name.

If so, then I would make sense to refer to the ’60s project as “The first Apollo missions”.

Maybe Kirk was just clumsily saying that the Apollo missions were the first to reach the Moon. In his impassioned enthusiasm, he stumbled over his word choice a bit. It happens to the best of us.

Re: Kirk and Apollo – don’t forget, too, that from his perspective Apollo happened 300 years ago. If you were off the cuff talking about a voyage of discovery that happened in the early 18th century, you might flub a few details, too….

I remember this episode mostly for having Diana Muldaur in it. Though a worn premise, it’s reasonably well executed and it pays off. I do like it that for once we’re not stuck with a standard ship in jeopardy plot. This works as well as it does because it lets the characters dictate the plot rather than the other way around. No doubt this episode is miles ahead of Catspaw and By any Other Name. And that’s because Sargon, Thalassa and Henoch were well developed characters to begin with. And we get to see Shatner and Nimoy play outside their comfort zone, which definitely helps.

I remember Nichelle Nichols venting some frustration implying that the story always favored the female guest star, while Uhura was stuck on the bridge.

I never really understood why Roddenberry didn’t keep John Meredyth Lucas as producer/showrunner for the following season. Coon recommended him, and he was clearly adept at the job.

I can see her point. I think that in the first season, you could say the same about some of the male guest stars supplanting regulars like Scott or Sulu. Imagine if Scotty had been the one bigoted against Romulans in “Balance of Terror,” or if Sulu had been the other Tarsus IV survivor in “The Conscience of the King.” As I said, ’60s TV was very guest-driven, so building stories around guest players rather than regulars was commonplace. But as time went on, the writers did tend to rely more on the main male semi-regulars. When Kirk didn’t get the love interest, it usually went to Scotty or Chekov. Scotty was the one accused of murder in “Wolf in the Fold,” when a guest crewmember might’ve worked better as a plausible suspect. Chekov often carried the subplots in episodes like “The Deadly Years” and “The Gamesters of Triskelion.” And “The City on the Edge of Forever” was actually rewritten to put McCoy in place of a guest character. We didn’t get that many prominent male guest crewmembers after season 1 — M’Benga and Garrovick are the only ones that stand out. (D’Amato was fairly prominent, but he was there to be killed off, and he was alongside Sulu anyway.) Meanwhile, we continued to get a lot of featured female guests while Uhura remained mostly in the background except in a few cases like “Mirror, Mirror” and “Gamesters” (where she was still overshadowed by a female guest anyway).

Yeah, that’s a puzzler. It would’ve helped season 3 a lot if it had been produced by someone with experience on the show.

One thing no one has mentioned that I always liked was the way they used different levels of light to indicate whether an alien or one of the crew is in the globe. It could even be viewed as being symbolic, the crew is dim compared to the super advanced aliens. Low tech but effective.

I remember seeing other glimpses of the android in the closing credit stills and a quick Google search indicates that A Piece of the Action and By Any Other Name are the episodes where they appear.

@1/Christopher: “…and maybe the Talarians from TNG’s “Suddenly Human,” who strike me as a possible Klingon offshoot — really, why should humans be the only ones they transplant?”

One thing I loved about the Errand trilogy of novels is they explicitly had a Klingon transplant colony (I think they even credited it to the Preservers?) as a major part of the story, similar to all the basically-human colonies throughout TOS.

As much as I would have liked to see more Uhura, I also love all the female guest characters. They kind of make up for the predominantly male main cast. And Diana Muldaur is one of the best.

I actually like all the guest stars in TOS, because they make the show feel more realistic. I watched the first season of “Enterprise” a couple of months ago, and it really bothered me that they have a crew of one hundred or so, but the only ones who ever do anything are the seven or eight main characters. It’s so implausible.

Shouldn’t Mulhall wear blue? Did they only give her a red uniform to have people wearing all three colours in the landing party?

As for Shatner’s acting, I think he had a difficult job here, because Kirk and Sargon have a lot in common – both are leading men, both are responsible and nice guys, and Kirk can be quite calm and serious too when he isn’t being playful. So Sargon is old and wise, but how do you play that? Nimoy’s job was much easier.

@20/Jana: “I also love all the female guest characters. They kind of make up for the predominantly male main cast.”

That’s an interesting point. It reminds me of the predominance of female guest characters in Trek fanfiction and tie-in fiction in the ’70s and ’80s. A lot of people today dismiss them all as “Mary Sues,” but that’s overlooking that “Mary Sue” was meant to be a parody of the worst examples of the practice, not the entire practice. The overwhelming majority of early fan authors were female, and I believe they tended to introduce strong, central female guest characters in order to balance out the male-dominated core cast. Your comment reminds me that there was some precedent for that in the show itself.

“Shouldn’t Mulhall wear blue?”

You could ask the same about Marla McGivers — surely a historian should be in the science department, not ship’s services. But I guess Roddenberry or whoever thought women looked better in red. Or maybe they just had more red female uniforms available because of all the yeomen-of-the-week.

And I’d say Muldaur had the hardest job when it came to differentiating her characters, since she only had a few minutes to establish Mulhall’s personality. I’m not sure she really did manage to differentiate Mulhall and Thalassa all that much.

Yay, Sulu’s back, even if he does say all of two sentences.

Another bit for Trivial Matters: at lieutenant commander, Mulhall is the highest-ranking female officer seen in the original series.

I always liked this episode. It definitely should have been a vehicle for Uhura, 60s conventions of favoring guest characters be damned. That aside, its still a good story, with Leonard Nimoy’s Henoch as the highlight.

One thing I never understood about this episode… Why is Henoch building Thalassa’s android? I thought they were each making android bodies for themselves, so wouldn’t she already have one of her own anyway? I don’t see how Henoch’s plan to keep Spock’s body would involve Thalassa transferring into Henoch’s android instead of her own. That just never made sense to me.

cScott @@@@@ 23 – I’m pretty sure Henoch’s point was not to have Thalassa transfer into his android body, but to convince her not to abandon the human body she was using at the time.

A few other thoughts, though not much original from what has been touched on already:

Like CLB @@@@@ 1, I, too wondered about the name of the episode. I was expecting some wibbly wobbly timey wimey stuff, so I was surprised to not see any. I find myself agreeing with Christopher, that it was the Arretans “returning to life” in what was tomorrow for them.

I loved Nimoy’s portrayal as Henoch. It’s always good to see the Vulcan shell come off.

But KRAD – It took you three sentences to figure out Henoch was going to betray them? I frankly assumed it would happen the moment Sargon identified one of the remaining “essences” as being from “the other side.”

According to BJO Trimble’s Star Trek Concordance (1995), the title Return to Tomorrow is a reference to Thomas Heywood’s play A Woman Killed With Kindness (1607), specifically Act IV, Scene 6.

@25/Paladin: Except that the verse quoted in the ’95 Concordance does not actually contain the words “return to tomorrow” in it. I think a lot of those “title references” in the ’95 edition were speculative, based on perceived similarity rather than certain knowledge of the writers’ intent.

(It does, however, contain the line “call back yesterday,” which is the name of my first Star Trek Adventures campaign, though I was quoting Richard II, Act 3 sc. 2.)

@26/CLB: I agree. The reference is not particularly relevant to the title or the episode.

I just love Diane Muldaur on all her Trek incarnations. I especially enjoy the embarrassment she and Shatner show as they return to themselves to find they are romantically embracing a near stranger.

@krad/I cannot change the laws of physics!:

Actually, he wasn’t dubious about engines the size of a walnut!

I’m not the biggest fan of this episode, although having watched it all of yesterday, I found it oddly more enjoyable than I remembered.

A few things of note: Sargon’s benevolence comes across as awfully deceptive. He turns the ship’s power off to disapprove of Spock not joining the landing party and then he transports only who he wants to come down. He hijacks Kirk’s body without even attempting to ask permission. I’m not entirely convinced that he would have taken “no” for an answer to all his ‘proposals’.

McCoy has the awesome, “I won’t peddle flesh!” line and is generally awesome in showing the appropriate medical concern throughout the episode. But I found it totally out of character when he whips out his phaser when Sargon takes control of Captain Kirk and demands Sargon leave the body. It’s awfully knee jerk even for McCoy.

I have to admit, I roll my eyes now everytime TOS drastically changes up the music for a dramatic introduction of a female guest star like they do in this episode. It’s like: “OMG, A BEAUTIFUL WOMAN!” In this day and age, it’s kind of wince inducing.

One interesting thing about Sargon’s chamber is the triangular red alcoves in the semicircle behind his pedestal. In TNG‘s “Contagion”, the Iconian ‘transporter room’ had diamond windows arranged in a similar manner. I’m betting that wasn’t coincidence.

And I always mix this episode up with Tomorrow is Yesterday, haha!

A class for writing tie-in fiction? That’s so cool! I’d like to take one of those.

A cool episode with a lot of issues. Just like KRAD, I was questioning why there were so few alternatives for Sargon and the rest. That speech by Kirk though! Easily one of my favorite moments in the series so far. Really, I loved how it gave the main players interesting things to do and act.

@30 – That tie-in fiction class does sound great, doesn’t it? KRAD, if you ever do anything like that online, count me in!

Just a quick note about the “Risk is our business” speech: if you ever get the chance to see the Shatner-starring comedy Free Enterprise, future Will & Grace star Eric McCormack does a fantastic version of that speech. He gets the tone and the pacing exactly right (and the movie’s a great deal of fun, period).

Free Enterprise is one of my absolute favorite movies.Mostly because it reminded me of me and all my friends (many of whom who were also all turning 30 in 1999, including me) and how we all behave.

And it led to one of my favorite convention stories.

I was at San Diego Comic-Con in 2006, and my friend Ashley Edward Miller — a screenwriter whose credits include Gene Roddenberry’s Andromeda, Fringe, Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles, Thor, and X-Men: First Class, among many others — introduced me to another of his friends, Robert Meyer Burnett, the director of Free Enterprise (and the template for Rafer Weigel’s Bob). I immediately fangoobered Robert because I love the movie so much, but Robert wasn’t really paying attention because he was so busy fangoobering me because he loved my Trek novel Articles of the Federation. So basically we were just each totally feeding the other’s ego. Meanwhile, Ash was just standing there with a shit-eating grin on his face……..

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

I have long marveled at how ‘Star Trek’ (TOS) was able to cast so many extremely beautiful women as guest stars (from the actresses who played Dr Helen Noel to Yeoman Martha Landon to Miramanee to android Andrea to dozens of others). However, it would appear that being on TOS did not really help their acting careers very much. Aside from Diana Muldaur (in this episode), Mariette Hartley (Zarabeth) and maybe Terri Garr (Roberta Lincoln), most of these actresses are not that successful. I wonder, did Trek hurt their careers?

@33/Palash Ghosh: Trek would’ve been just one of the many TV series that these actresses were doing guest spots on — a gig they did for a week before moving on to the next gig and the next and the next. It makes no sense to single it out as having more influence than all the rest. It’s just common sense that the majority of people in any profession will have average or unsuccessful careers and only a limited number will have great success.

However, you’re overlooking that Sherry Jackson (Andrea) had already had a successful career as a child actress well before appearing in Trek, noted for several movie appearances and a regular role in the first 5 seasons of The Danny Thomas Show. Once she grew up, she was pretty much ubiquitous in sexpot roles in ’60s and ’70s TV shows and B-movies, with Andrea being just one of many.