At the dawn of the ’90s, a film was released that was so quirky, so weird, and so darkly philosophical that people who turned up expecting a typical romantic comedy were left confused and dismayed. That film was Joe Versus the Volcano, and it is a near-masterpiece of cinema.

There are a number of ways one could approach Joe Versus the Volcano. You could look at it in terms of writer and director John Patrick Shanley’s career, or Tom Hanks’. You could analyze the film’s recurring duck and lightning imagery. You could look at it as a self-help text, or apply Campbell’s Hero Arc to it. I’m going to try to look at it a little differently. JVtV is actually an examination of morality, death, and more particularly the preparation for death that most people in the West do their best to avoid. The film celebrates and then subverts movie clichés to create a pointed commentary on what people value, and what they choose to ignore. Plus it’s also really funny!

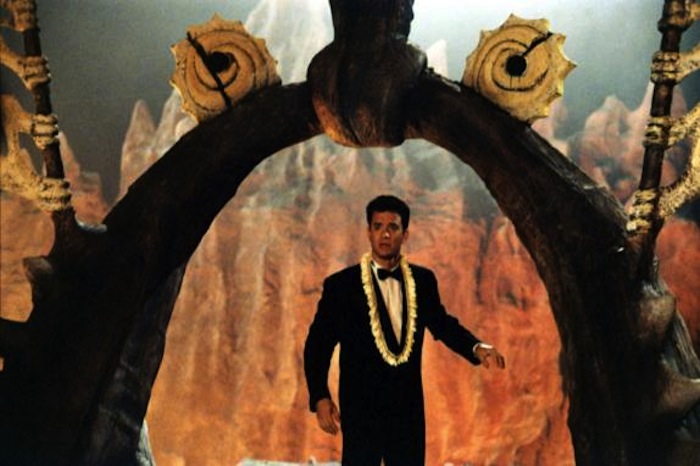

The plot of JVtV is simple: sad sack learns he has a terminal illness. Sad sack is wasting away, broke and depressed on Staten Island, when an eccentric billionaire offers him a chance to jump into a volcano. Caught between a lonely demise in an Outer Borough and a noble (if lava-y) death, sad sack chooses the volcano. (Wouldn’t you?) Along the way he encounters three women: his coworker DeDe, and the billionaire’s two daughters, Angelica and Patricia. All three are played by Meg Ryan. The closer he gets to the volcano the more wackiness ensues, and the film culminates on the island of Waponi-Wu, where the Big Wu bubbles with lava and destiny. Will he jump? Will he chicken out? Will love conquer all? The trailer outlines the entire plot of the film, so that the only surprise awaiting theatergoers was…well, the film’s soul, which is nowhere to be seen here:

See? First it makes it look like the whole film is about a tropical paradise, and it looks silly. It looks like a movie you can take your kids to. Most of all, it looks like a by-the-numbers rom-com. At this point, Meg Ryan was coming off of When Harry Met Sally, and was America’s biggest sweetheart since Mary Pickford. Tom Hanks had mostly appeared in light comedies like Big and Splash, with occasional poignant performances in Punchline and Nothing In Common hinting at the multi-Oscar-winner within. The two of them teaming up for what looked like a silly rom-com, directed by the guy who wrote Moonstruck? This was a sure bet for date night. In actuality, Joe Versus the Volcano is a work of profound crypto-philosophy, more on par with Groundhog Day than You’ve Got Mail. It’s also a fascinating critique of the capitalism celebrated in ’80s movie clichés. Let’s start by looking at the film’s unique, convention-defying depiction of work.

16 Tons… of Capitalism!

Most movie jobs were glamorous in the ’80s: Beverly Hills Cop and Lethal Weapon made being a cop look like a constant action montage; Broadcast News made journalism look like nail-biting excitement; Working Girl and Ghostbusters both make being a secretary look fun as hell. In When Harry Met Sally, a journalist and a political consultant apparently work 20 hours a week (tops) while pursuing love and banter in a New York City devoid of crime, overcrowding, or pollution. In Shanley’s previous script, Moonstruck, Nic Cage is a baker who is passionate about his work, Cher is an accountant we never see doing math, and both are able to throw together glamorous opera-going evening wear on a day’s notice. And going a little further into the future, Pretty Woman gives Mergers & Acquisitions—and prostitution—the exact same sheen. What I’m getting at here is that in most of the popular films of the era, jobs were fun, fluffy, a thing you did effortlessly for a few hours before you got to the real work of being gorgeous and witty on dates.

“Leah!” I hear you scream. “Why are you such a buzzkill? Who in their right mind wants to watch a comedy about the tedium of work?” And I see your point. But! I think it’s also worth noting that at a certain point, the economic unreality of an escapist film can undermine your pleasure in watching it. It’s nice to see a movie that acknowledges the reality that most of us live in, where we get up earlier than we want to, and sit at a desk or a cash register (or stand at an assembly line or in front of a classroom) for far longer than we’d like to, all to collect money that still won’t cover the fancy dinners and immaculately tailored clothing that are paraded through these films. So I think it’s important to note that Joe Versus the Volcano gives 20 minutes of its hour-and-42-minute runtime to the horrors of Joe’s job at American Panascope (Home of the Rectal Probe). And it’s significant that the first thing we see as people trudge to their jobs is Joe literally losing his sole.

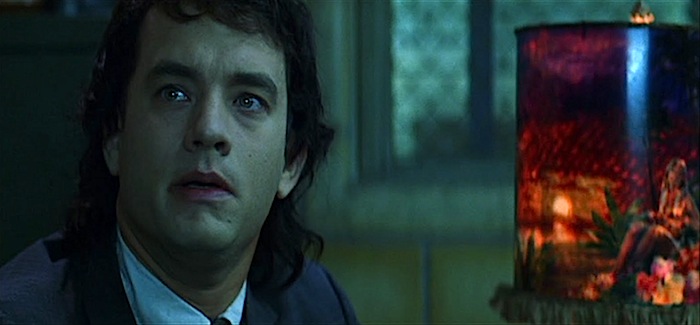

I’ve never seen the soul-sucking despair of a bad job summed up better than in this scene. And as if that hellish circular conversation isn’t enough, there’s the green light, the buzzing flourescents, the coffee that can best be described as ‘lumpy’, and the coworkers, who are just as sad and defeated as Joe. Watching this, I’m reminded of all the crap jobs I’ve taken to pay my bills, which I can only assume was the point: rather than the fairytale careers of most rom-coms, JVtV was trying to dig closer to the exhaustion that lies at the heart of American capitalism. Against this despair, Joe makes only a single palliative gesture: bringing a musical lamp in as a Band-Aid to a gushing wound.

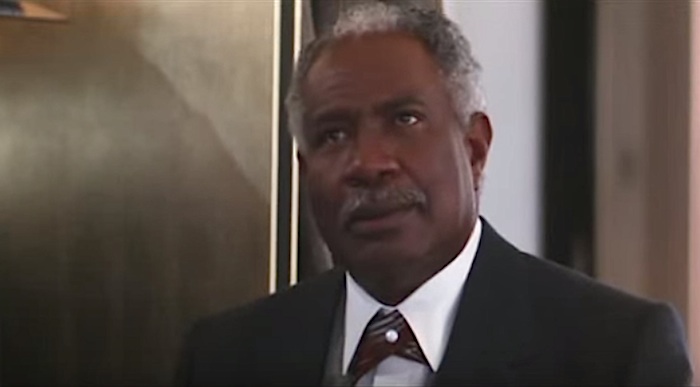

This lamp is promptly banned by his awful boss, Mr. Waturi, not for any logical reason—it isn’t distracting Joe or his coworkers, it certainly doesn’t detract from his work—but because Waturi thinks it’s frivolous. Work isn’t supposed to be fun in Mr. Waturi’s mind, and since he’s the boss he’s allowed to humiliate his worker by treating him like a child, at the same moment that he demands his worker put away childish things. Waturi is a walking Catch-22. But there’s something else at work here… Waturi is choosing to turn this office into a circle of hell. And Joe chose to leave his old job at the fire department, as he chooses each day not to look for better work. They’re all accepting that life is supposed to be nothing but toil and the grave, and that anything beyond that is somehow wrong. Waturi even mocks the idea that a normal adult could feel “good”—”I don’t feel good! Nobody feels good! After childhood, it’s a fact of life.”

The first 20 minutes of the film are so bleak, in fact, that when Joe is finally diagnosed with a terminal ‘braincloud’ his impending death comes as a relief. This moment is even coded as comforting in the film: where Mr. Waturi’s basement is a hideously green, fluorescent dungeon, the doctor’s office is warm and wood paneled, lit by small glowing lamps and a roaring fire. It’s the first inviting space we’ve seen in the film, and we’re only there, with Joe, to learn that he’s going to die. Then we’re shunted back to the office, where we have to confront the realities of capitalism again. Joe doesn’t have any savings, he can’t afford to go on a final trip, there’s a hole in the bucket list, but Joe has to quit. Even with that horror written on his face, he uses his last moments at American Panascope to appeal to his boss and coworkers. Surely they can see that life in this office is actually a living death?

When Waturi, sneers at him, “I promise you, you’ll be easy to replace!” Joe snaps, pushes Waturi against the wall, and yells, “And why, I ask myself, why have I put up with you? I can’t imagine, but now I know. Fear. Yellow freakin’ fear. I’ve been too chicken shit afraid to live my life so I sold it to you for three hundred freakin’ dollars a week! My life! I sold it to you for three hundred dollars a week! You’re lucky I don’t kill you!” This is the first time it becomes explicit: Joe has been selling his life without questioning the transaction (the way most of us do), and only now that he sees an endpoint does he realize how much more he was worth. This distillation of life into money is made even more explicit the next morning, when Samuel Graynamore shows up at his door.

Graynamore is the ultimate capitalist: he makes giant sums of money by owning a manufacturing plant that uses a substance called “bubaru”. He doesn’t know what the hell bubaru is, only that he needs it, and it’s expensive. He can get it from a Celtic/Jewish/Roman/South Pacific tribe called the Waponi-Wu, and he doesn’t know anything about them either—just that they’ll give him their bubaru in exchange for a human sacrifice to their volcano. He stresses that the life must be “freely given”, and promptly offers Joe an enormous sum of money to go jump in the volcano. Graynamore lays his credit cards out like a poker hand for Joe to consider: an American Express Gold, a Diner’s Club card, a Visa Gold and a Gold MasterCard, and says, “These are yours—if you take the job.” He also rattles off the perks, including a first class plane trip and hotel stays, and then finally tries for a slightly more inspiring line, “Live like a king, die like a man, that’s what I say!” (Which obviously begs the question: Why isn’t he doing it?) Joe, who has already discussed the fact that he has no savings, looks around his bleak, ramshackle apartment, picks up the MasterCard and examines it. He says, “All right I’ll do it,” in the tone of a man agreeing to run to the store for more beer, but really, what choice does he have? If we want to look at this scene positively, he’s trading 5 months of life with no money and a painless death for a few weeks of extreme money, adventure, and a death that will be terrifying and extremely painful, but also intentional. Of course, we can also see this is a horrifyingly bleak business transaction, in which Joe is literally selling his life now that he’s gotten a better offer than $300 a week.

Of Blue Moons and Pretty Women

Before Joe can make his journey, he needs to prepare himself, which leads to one of the best shopping montages of the era. (This is weird, because don’t people facing death shed their material goods, normally?) But what’s more interesting is that, just as the first 20 minutes of the film skewers the typical career paths of rom-com heroes, the shopping montage turns into a critique of the aggressively capitalist movies of the ’80s. Think about it, in Die Hard Hans Gruber pretends to have lofty political ideals in order to pull off a heist, and his entire view of the world comes from magazines; Back to the Future is largely about Marty wanting the trappings of upper middle class life; any John Hughes’ movie could be retitled #firstworldproblems with no loss of emotional resonance. Here things are a little more complicated, but we’ll need to take a closer look at one of cinema’s most iconic shoppers to tease out what JVtV is doing.

Pretty Woman premiered two weeks after JVtV, to much better box office numbers, went on to become a staple of cable television, and references to Pretty Woman have dotted the TV and movie landscape ever since the mid-90s. For those who don’t remember: a sex worker named Vivian is given a credit card by her john-for-the-week, Edward. He asks her to buy some suitable clothes so she can act as his date for various rich-guy events (the opera, polo matches, the usual). She goes to Rodeo Drive, where her appearance is mocked by snooty saleswomen. She realizes that without an aura of class, Edward’s money will get her nowhere. Luckily, the hotel’s concierge sets her up with an older, female tailor, and then Edward takes her shopping again the next day, and finally leaves her with multiple credit cards so she can go on a spending spree.

This is presented in the film as a triumph; Vivian sticks it to the man by buying clothes with another man’s money, and the snotty saleswomen are punished for being… small-minded? I guess? And of course they are punished specifically by being taunted over their lost commission. Which again, snobbiness does indeed suck, but perhaps I’m just not seeing a feminist victory in a broke sex worker celebrating capitalism, but only after two older men help her, and only at the expense of two other women (who probably can’t afford to buy any of the stuff they sell). This celebratory spending spree is the scene set to Roy Orbison’s Pretty Woman. Not the opera scene, or Richard Gere’s declaration of love, no—the emotional peak of this film comes on Rodeo Drive. Even more tellingly, it only comes after Edward has ordered the workers out of a hotel bar, so he can have sex with Vivian on top of the bar’s (very public) grand piano. There is no way to ignore the financial transaction happening here.

In JVtV, the shopping trip unwinds a little differently. Joe is also given a spending spree by an older man, and he does splurge on extravagant things after a life of being a have-not. Unlike in Pretty Woman, however, Joe is never humiliated by any of the shop people, even though his initial appearance borders on slovenly (and even though, in my experience at least, Manhattan is a far snottier place than L.A.) Even more importantly: Joe is not being paid for his sex—he’s being paid for his death. Which casts the whole spree in a desperate, absurdist light, rather than a triumphant one.

Yes, he gets an Armani tux, but we later learn it’s the suit he plans to die in. Yes, he gets a haircut, but when he does it’s not a huge reveal of a new beauty—rather Marshall, the chauffeur who’s been driving him around (more on him in a sec) says, “You’re coming into focus, now”. This underscores the idea that it isn’t the money that’s transforming Joe. Joe has been lazy, and since he left the fire department he’s been letting life knock him down, and allowing others to define him rather than defining himself. Faced with the end of his life, he’s finally trying to figure out who he wants to be. The post-makeover shopping spree follows Joe as he buys absurd, frivolous things: ginormous umbrellas? A mini-bar inside a violin case? A mini putting green? Four steamer trunks? And yet, like someone in a Resident Evil game or a D&D campaign, he uses each item during the rest of his adventure. And where Vivian saves Edward’s elitist cred by wearing that brown polka dotted dress to the polo match, Joe saves Patricia Graynamore’s life with the ridiculous umbrella and the mini-bar. On the surface, the shopping sequence is essentially the fun, boy version of Pretty Woman, or the even-more-whimsical version of Big.

Except.

At the end of the spree he asks Marshall to come out to dinner with him, and Marshall refuses. He has a family to go home to. And Joe quickly admits that this is for the best. He’s changed his outward appearance, but that hasn’t really touched his interior life, and he still needs to prepare himself to die. After all, as Joe realizes, “There are certain doors you gotta go through alone.”

Now, about Marshall. The timing is slightly off on this, but I choose to assert that the whole sequence with Marshall is a critique of the Magical Negro crap in general, and Driving Miss Daisy in particular. (DMD was a stage show prior to becoming a movie, so the critique could be based on that…) Marshall picks Joe up, things seem perfectly pleasant, but then Joe starts asking Marshall, the older black man, for help in picking out a suit…. but the suit is, of course, metaphorical. Marshall calls him out on this, saying “They just hired me to drive the car, sir. I’m not here to tell you who you are… clothes make the man, I believe that. I don’t know who you are. I don’t want to know. It’s taken me all my life to find out who I am, and I am tired. You hear what I’m saying?” Even though Marshall takes pity on him and takes him shopping, he doesn’t offer any mystical wisdom, and Joe doesn’t ask him for life advice or tell him he’s dying. At the end of the day when Joe asks Marshall to dinner, Marshall refuses. I remember watching this as a kid and being confused. You see, I watched a lot of movies, so I expected a smash cut to Joe sitting at a dining table with Marshall and his warm, loving family. This would be how Joe spent his last night before his journey, welcomed into a family that wasn’t his, fortified by their love for the difficult task ahead of him. Perhaps he’d even have some sort of rooftop heart-to-heart with the youngest child? At some point, surely, he’d confess that he was dying, and Marshall’s family would offer some sort of solace? But no. The point of this is that Marshall has his own life. He’s not just there as a prop to Joe’s spiritual enlightenment, and Joe isn’t going to become some surrogate son to him after a few hours—Marshall has his own children, his own style, and a job he seems to enjoy. He’s chosen to build a life for himself, while Joe has held life at arm’s length. Small Leah was baffled.

Even better, the film avoids the other obvious plot twist: the minute Joe bought Marshall the tux, my childhood brain began unspooling a montage of the two hitting the town together for a super fancy boys’ night out. But again, nope. Joe is alone for his last night in New York, which is really his last night in his old life. The movie doesn’t have him engage with anyone, he simply eats dinner (alone), drinks a martini (alone), and goes to bed in his posh hotel room (alone) where we see him lying awake. This sequence is set to “Blue Moon”, which is all about solitude, but as the song echoes and the camera fixes on Joe’s sad, desperate eyes, we’re reminded that while this spree has been fun, its entire point is to prepare him for his final journey.

All You Need Is Lovin’?

There is a trio of women in the film who are all, in what I’m assuming is a nod to Nikos Kazantzakis, played by Meg Ryan. This was Ryan’s first film after When Harry Met Sally, and Shanley’s first after Moonstruck, so (especially given the quirky trailer) audiences probably expected a fun movie bursting with colorful locations, swoony romance, and neuroses that serve to strengthen relationships. What they got instead were three variations on women whose neuroses were too real to be endearing.

DeDe seems like she could have walked in off the set of Moonstruck, actually. She nursing a constant sniffle, cowed by Mr. Waturi, overwhelmed by Joe’s new enthusiasm for life, but when she learns that Joe is dying she’s scared off—she has her own life, and is not ready to attach herself to someone who will leave her in a few months. Each time I watch the film, I vacillate: Is DeDe a jerk for abandoning Joe? Or is Joe the jerk for laying his terminal diagnosis on her just as they’re about to take things to a different level? Or is Joe a jerk for asking her out at all, when he know he only has six months to live?

Then we meet the Graynamore sisters. Back in 2007, AV Club writer Nathan Rabin coined the phrase Manic Pixie Dream Girl to sum up a type of character common to rom-coms, and JVtV’s Angelica Graynamore seems to be a prescient critique of that stock character. She’s a poet and artist, she has the bright red hair and unnaturally green eyes of romance heroine, her clothes are ridiculously colorful, and she drives a convertible that matches her hair. To top it all off, she refers to herself as a “flibbertigibbet” (giving her about an 8 on the MPDG scale, in which 1 = “wearing a helmet and loving The Shins” and 10 = “actually being Zooey Deschanel”) but we soon learn that she can only afford all this quirkiness and spontaneity on her father’s dime. Her failures as an adult and an artist eat away at her soul, and within a few hours she’s asking Joe is he ever thinks about killing himself.

Joe: What… Why would you do that?

Angelica: Why shouldn’t I?

Joe: Because some things take care of themselves. They’re not your job; maybe they’re not even your business.

But… Joe is killing himself. Sure, he’s going to die in a few months anyway, but he’s choosing to go leap into a volcano. That’s certainly not letting his death take care of itself. But he doesn’t offer that information, and she lashes out at him:

Angelica: You must be tired.

Joe: I don’t mind talking.

Angelica: Well, I do! This is one of those typical conversations where we’re all open and sharing our innermost thoughts and it’s all bullshit and a lie and it doesn’t cost you anything!

Again he’s being given a pretty open shot to talk about the purpose of his trip, but he chooses not to, and when Angelica offers to come up to his room he refuses physical intimacy just as she has rejected emotional intimacy. Joe decides to ignore the fancy suite Graynamore bought him, and instead spends another night alone, sitting on a beach, gazing at the Pacific Ocean.

Finally Patricia, Graynamore’s other daughter, seems like the tough-minded, independent woman who will be softened by love, but no: she describes herself as “soul sick”:

I’ve always kept clear of my father’s stuff ever since I got out on my own. And now he’s pulling me back in. He knew I wanted this boat and he used it and he got me working for him, which I swore I would never do. I feel ashamed because I had a price. He named it and now I know that about myself. And I could treat you like I did back out on the dock, but that would be me kicking myself for selling out, which isn’t fair to you. Doesn’t make me feel any better. I don’t know what your situation is but I wanted you to know what mine is not just to explain some rude behavior, but because we’re on a little boat for a while and… I’m soul sick. And you’re going to see that.

Patricia isn’t the antidote to Angelica’s darkness, and she’s not just a sounding board for Joe’s problems. She has her own struggles. When, in the end, she chooses to join Joe at the lip of the volcano, she makes it clear that she’s not doing this for him, she’s making her own choice to jump. Like Angelica, she is drawn to darker questions, but where her sister, and Joe, see only an ending, Patricia embraces the mysteriousness of existence, and says of the volcano: “Joe, nobody knows anything. We’ll take this leap and we’ll see. We’ll jump and we’ll see. That’s life.”

A Brief Note About DEATH

The two people who learn that Joe is dying, DeDe and Patricia, recoil in fear. Again, this is 1991, and this might be a stretch—but how many AIDS patients witnessed exactly that panic when they told their friends and family members? How many went from being loved ones to being objects of fear and pity? One of the through lines of the film is that, from the moment Joe gets his diagnosis, he’s alone. He alone in the hotel after Marshall leaves. He’s alone on the beach after he asks Angelica not to spend the night. He’s essentially alone when he has his moon-based epiphany, because Patricia’s unconscious. And in the end he has to face the volcano alone…until he doesn’t. Patricia, who has talked a good game about being awake and conscious of life, makes the choice to stand next to him. She grabs his hand, and says that since “no one knows anything”, she might as well take the leap with him.

A Brief Note About LUGGAGE

Joe has no family, and seemingly no friends. He has no one to say goodbye to as he leaves New York. No one will miss him, no one will mourn him. Before he sets off on his voyage, he acquires THE LUGGAGE, four immaculate Louis Vuitton steamer trunks (that, I assume, directly inspired Wes Anderson’s own spiritual-quest movie The Darjeeling Limited) that become Joe’s home after Patricia’s boat sinks. The luggage-raft serves as a perfect floating master class in metaphor. Joe has a lot of baggage in the form of neuroses and hypochondria, but he has no weight—nothing ties him to life. Once he buys his luggage, he has a physical tether, in the form of ridiculous bags that he has to cart around everywhere. But rather than taking the obvious route and having Joe abandon his baggage as he gets closer to the Big Wu, the movie follows its own crooked path. The luggage is what allows him to float, and becomes the site of ridiculous dance sequences, a mini-golf game, and a spiritual epiphany.

Old Man River Just Keeps Rolling Along

Remember when I said that Pretty Woman‘s emotional high point was a shopping montage? JVtV’s peak comes a few days after the sinking of the Tweedle Dee, when Joe, sun-addled and delirious from dehydration, watches the moon rise. Where John Patrick Shanley’s Moonstruck used the moon as a symbol of true love, here it’s a distant, literally awe-inspiring stand-in for… God? Life? Consciousness itself? Joe is overwhelmed by it as it rises over the horizon. As in his last nights in New York and L.A., he’s alone—Patricia is still unconscious, there are no crewmates or friends, it’s just him and the moon. After all of his preparations, Joe is able to face the fact that he’s alive, but that he won’t be for much longer.

I’ve been trying to write about this scene for a while now, and I always dance around it. There are a few reasons for that. One of them is personal: going with my mother to my grandparents’ house, watching as she washed and fed them; as my 1950s beauty school graduate mother clipped her hair short and neat, and then held a hand mirror up to show my grandmother the nape of her neck, as though my grandmother would have an opinion, or be able to voice it. I studied the way my mother engaged with her mom’s nonsense, or backed away from it. I recoiled from the utter dehumanization of my grandfather, lying in a hospital bed under glaring fluorescent lights, as his children discussed his body’s will to live. The moment I, without fully realizing it, jerked my partner by the shoulder to turn both of us away when I realized the nurse was about to change my grandfather’s gown in front of us, as though this stranger was a harried mother with a baby.

Joe will be prepared for his death, too, but only in the lightest, most absurd manner. He will retain his agency, his appearance, his dignity. As a child I couldn’t accept that. Death was not a flower-strewn path, or a marshaling of one’s self. It was a slow degradation under flickering pale light. Death was the beginning of the movie, it was the “life” that Joe had escaped. Joe had already cheated death, I thought. If they still could, my grandparents would choose to be that person under the moon, arms raised, accepting and alive. Why was Joe throwing it away?

I think I can answer that question now, as an Older, Grizzled Leah. The version of JVtV that’s a wacky rom-com doesn’t need this scene—it just needs to get to the crazy, orange-soda-guzzling Waponi, and for Joe and Patricia to confess their love for each other as fast as possible, so Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan can twinkle their cute little eyes at each other. But the version of JVtV that is a manual on the preparation for death needs this scene.

Joe has acquired and now shed the trappings of a fancy, elite male life. He has tried to woo women, failed, and instead attempted to attain emotional closeness with them. He has spent all of the nights since his terminal diagnosis alone, and has realized that he’d rather learn about other people than meditate on himself. Over the course of the film, Joe goes from having a long, tedious life rolling out in front of him, to knowing he only has six months to live, to believing that he only has a few weeks to live, to, now, facing his death from dehydration within a few days. As his time shrinks, Joe allows himself to open up to the enormity of life itself. Now that he knows exactly what he’s been wasting, and what he’ll be losing, he’s ready to go.

But what’s most significant in this scene is that Joe doesn’t ask for anything. He just says thank you, and while Joe addresses his gratitude to “God”, he also qualifies this address by saying “whose name I do not know”—which maintains the movie’s denominational agnosticism. I know I keep harping on Groundhog Day, but I think it’s important to note that we never learn why Phil Connors is repeating February the 2nd. Phil and Rita both have Catholic backgrounds but there’s no indication they still practice that faith, and there’s certainly no invoking of Jesus, Mary, Ganesha, L. Ron Hubbard, or any other avatar that would drive people screaming from the theater or couch—they only mention God in passing. As a result, the film can be as meaningful for hardcore atheists as for Buddhists as for Christians. In the same way, Joe Versus the Volcano talks about people losing their souls, but not to sin or hell, just to the grind of everyday life. When Joe directly asks Patricia if she believes in God she replies that she believes in herself, and when he directly thanks “God” he sidesteps what that word means to him.

Take Me! To! The VOLCANO!

After the shocking sincerity of this scene, we are thrown into the full-bore silliness of the Waponi. They are the descendants of a contingent of Druids, Jews, and Romans who shipwrecked at the base of the Big Wu and married into the native families of the island. Thus, Shanley removes the Waponis from the horrors of colonialism, sidesteps the possible fetishizing of the island people, and allows Abe Vigoda and Nathan Lane to be credible tribespeople. (I just wish they’d found a second role for Carol Kane…)

Of course the sojourn with the luggage means that all of the sand has run out of Joe’s hourglass. He has to jump into the Big Wu as soon as possible. He and the Chief discuss this, with the Chief showing Joe and Patricia his “Toby”—his soul—which looks like a small palm husk doll. The Chief once again asks his people if any of them are willing to make the sacrifice for the rest of the tribe, but they all shuffle their feet and stare awkwardly at the ground. Joe is given several outs here: the Chief doesn’t want him to jump, he wants one of the tribespeople to do it. Patricia confesses her love for him, insists they get married, and then tries to talk him out of it. As a kid, I kept waiting or some sort of deus ex machina to swoop in and provide a loophole. Surely the hero wouldn’t have to go through with this insanity?

I’ve always been drawn to narratives about death. My family suffered losses in its past that shaped my own life. I spent high school tensing every time the phone rang, knowing that the voice on the other end might be telling me that my mentally-troubled friend was gone. I studied religion at least in part because learning about those systems of belief, and their varying attitudes toward death, calmed me, and also forced me to face my fears on a nearly daily basis. Maybe because of my past, or maybe because of chemistry, I spent a few years in my early 20s waking up each morning with death on my chest.

So I’ve also always sought out narratives to help me process that fact. I love that Harry Potter has to walk into the Forbidden Forest to face Voldemort, that Luke goes to the second Death Star knowing that the Emperor will kill him, that Meg Murry walks back into Camazotz knowing that she can’t defeat IT, and that Atreyu battles Gmork rather than just sitting back and waiting for The Nothing. But the thing about JVtV that sets it apart from those stories, the thing that bothered me so much as a child, is the same thing that makes me love it even more now. All of those other narratives? They are all fundamentally about control. The hero faces death, yes, but they also triumph over their fear. In JVtV, Joe has his moment on the luggage-raft, but then he still has to walk up the volcano… and he’s still openly terrified of jumping. This made Small Leah squirm and back away from the TV. Shouldn’t he and Patricia at least be brave and quippy? Heroes are supposed to be brave and quippy. If this fictional character couldn’t face death with dignity, how could I? And then he and Patricia jump but get blown back out of the volcano, and this mortified me. WTF was this shit? Noble sacrifices are supposed to be noble, duh. This was ridiculous. Insulting.

But of course Joe’s death in the volcano is absurd, and the miracle that blows him back out is ridiculous. Life is ridiculous, random, violent, and frequently more trouble than it’s worth. We are all being manipulated by billionaires right this minute, and we all have brain clouds.

I have never jumped into a volcano. But I am on the lip of one all the time, and so are you, reading this right now. Rather than lying to us and making that somber and orderly, the movie embraces the absurdity by throwing Waponis and luggage salesmen at us, but also giving us that raft scene, and also making us walk up the mountain with Joe. There is no control here (possibly this is why audiences rejected it?) and all of Small Leah’s attempts to plan, and High School Leah’s attempts to manage her friend’s care, and College Leah’s attempts to commit theological systems to memory, cannot even make a dent in that. But throwing myself into the silliness still helps.

If the movie is a meditation on death, the preparation for death, and society’s reaction to it, then that arc culminates in that scene on the luggage-raft. But the film is also making a point about life, and the need to avoid losing your soul/Toby/humanity. We need to see the joyful silliness of the Waponis balanced with the real fear that Joe has in the face of the volcano. This sequence is perfectly complicated: Joe has come to terms with his death, but wants to live, but has made a promise to the Waponis that he needs to honor. The Waponis are silly and hilarious, but to fulfill the film’s critique of capitalism, we also see that they’ve allowed themselves to become spiritually bankrupt by trading bubaru for orange soda (gosh that was fun to type) and more importantly by refusing to make a larger sacrifice for their community. The life that goes into the volcano is supposed to be freely given, right? But Joe’s life (and, to an extent, Patricia’s) was bought by Samuel Graynamore. The moment that Small Leah found unbearably cheesy now plays as a necessary fairy tale ending, with the adult twists that the Waponis are wiped out, the crew of the Tweedle Dee is dead, Joe and Patricia are now married and need to make that relationship work for longer than five minutes, it seems likely that Joe’s new father-in-law almost murdered him… and that’s all before we address the fact that the newlyweds are drifting through the South Pacific on luggage, with no land in sight.

I’ve often wondered about this in the years since I did that college rewatch: would JVtV be a hit today? When the “Cynical Sincerity” of Venture Brothers, Community, Rick & Morty, and Bojack Horseman can create cults, the blindingly pure sincerity of Steven Universe can inspire a giant fandom, and both a square like Captain America and the snark-dispensing machine that is Deadpool are embraced with box office love—would JVtV find an audience? Would people welcome its mix of silliness and gut-wrenching soul? Because here’s the most important bit: the silliness is necessary. As in Groundhog Day, which balances its irony and sincerity with perfect precision, JVtV is as much about the sheer joy of dancing on a luggage-raft as it is about the numb depression of Mr. Waturi’s office. The film’s point is that the most important goal in life is simply to remain aware of, to borrow a phrase from Neutral Milk Hotel, “how strange it is to be anything at all.” The point of the journey is to make thoughtful choices about how to live, and the volcano is life itself.

Leah Schnelbach had no idea she has so many thoughts about Joe Versus the Volcano? Man, nobody get her started on The ‘Burbs. Come memento her mori on Twitter!