Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

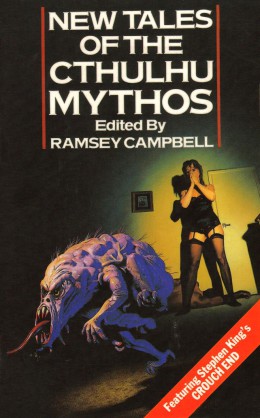

Today we’re looking at Stephen King’s “Crouch End,” first published in New Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (Edited by Ramsey Campbell) in 1980.

Spoilers ahead.

“Sometimes,” Vetter said, stealing another of Farnham’s Silk Cuts, “I wonder about Dimensions.”

Summary

American tourist Doris Freeman totters into a police station just outside the London suburb of Crouch End. To constables Vetter and Farnham, she describes the disappearance of her husband, Lonnie.

They came to Crouch End to dine with Lonnie’s colleague John Squales, but Lonnie lost the address. Their cab driver stops at a phone box so he can call for directions. Doris spots a strange headline in a newsagent’s window: “60 Lost in Underground Horror.” Leaving the cab to stretch her legs, she spots more weirdness: momentarily rat-headed bikers, a cat with a mutilated face, two children (the boy with a claw-like hand) who taunt them and then run away.

Worse, their cab unaccountably deserts them. They start to walk toward Squales’s house. At first Crouch End looks like a modestly affluent suburb. Then they hear moaning from behind a hedge. It encloses a lawn, bright green except for the black, vaguely man-shaped hole from which the moans issue. Lonnie pushes through to investigate. The moans become mocking, gleeful. Lonnie screams, struggles with something sloshing, returns with torn and black-stained jacket. When Doris stares transfixed at a black (sloshing) bulk behind the hedge, he shrieks for her to run.

She does. They both do, until exhausted. Whatever Lonnie saw, he can’t or won’t describe it. He’s shocked, nearly babbling. Screw dinner, Doris says. They’re getting out of Crouch End.

They pass up a street of deserted shops. In one window is the mutilated cat Doris saw earlier. They brave an unlit underpass over which bone-white trains hurtle, heading, they hope, toward sounds of normal traffic. Lonnie makes it through. But a hairy hand seizes Doris. Though the shape in the shadows asks for a cigarette in Cockney accent, she sees slit cat eyes and a mangled face!

She wrenches free and stumbles out of the underpass, but Lonnie’s gone and the street’s grown stranger. Ancient warehouses bear signs like ALHAZRED, CTHULHU KRYON and NRTESN NYARLATHOTEP. Angles and colors seem off. The very stars in the plum-purple sky are wrong, unfamiliar constellations. And the children reappear, taunting: Lonnie’s gone below to the Goat with a Thousand Young, for he was marked. Doris will go, too. The boy with the claw-hand chants in a high, fluting language. The cobblestoned street bursts open to release braided tentacles thick as tree trunks. Their pink suckers shift to agonized faces, Lonnie’s among them. In the black void below, something like eyes –

Next thing Doris knows she’s in a normal London street, crouching in a doorway. Passersby say they’ll walk her to the police station until they hear her story. Then they hurry off, for she’s been to Crouch End Towen!

A nurse takes Doris away. Veteran constable Vetter tells noob Farnham that the station “back files” are full of stories like hers. Has Farnham ever read Lovecraft? Heard the idea that other dimensions may lie close to ours, and that in some places the “fabric” between them stretches dangerously thin?

Farnham’s not much of a reader. He thinks Vetter’s cracked. It’s funny, though, how other constables at the Crouch End station have gone prematurely white-haired, retired early, even committed suicide. Then there’s Sgt. Raymond, who likes to break shoplifters’ fingers. It’s Raymond who explains that the “Towen” Doris mentioned is an old Druidic word for a place of ritual slaughter.

Vetter goes out for air. After a while Farnham goes looking for him. The streetlights towards Crouch End are out, and he walks off in that direction. Vetter returns from the other direction, and wonders where his partner’s gone.

Farnham, like Lonnie, disappears without a trace. Doris returns home, tries to commit suicide, is institutionalized. After her release, she spends some nights in the back of her closet, writing over and over, “Beware the Goat with a Thousand Young.” It seems to ease her. Vetter retires early, only to die of a heart attack.

People still lose their way in Crouch End. Some of them lose it forever.

What’s Cyclopean: Nothing, but there are “eldritch bulking buildings.” Someone should do a survey of which adjectives neo-Lovecraftians most often use to honor the master.

The Degenerate Dutch: King’s working class casts are prone to racism, sexism, and a general background buzz of other isms. Ambiguously gay characters like Sergeant Raymond tend to be Not Nice. And like many of King’s stories, “Crouch End” walks the fine line between body horror and ablism and falls off the wrong side—if you’re scarred or have a birth defect, then congratulations, you’re a servant of the elder gods.

Mythos Making: The Goat With a Thousand Young takes her sacrifices from the London suburbs; Cthulhu owns a warehouse.

Libronomicon: Aside from Lovecraft himself, the only book mentioned is a “Victorian pastiche” called Two Gentlemen in Silk Knickers. Unclear whether it’s a pastiche or a pastiche ifyouknowwhatImean.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Farnham assumes Doris is crazy. And Lonnie, in the brief period between initial encounter and consumption, is working hard on a nice case of traumatic dissociation.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

A good horror writer is more frightened than you, and manages both to make that fear contagious and project it onto something worth being afraid of. King is very, very good at this. His descriptions of terror are visceral. They range from the hyperfamiliar—who hasn’t had moments of I can’t I can’t I can’t?—to ultraspecific mirror neuron triggers, the fear-dried mouth tasting sharply of mouthwash.

Lovecraft sometimes manages this, but frequently lacks the needed self-consciousness. He doesn’t entirely realize what parts of his experience are universal, so you get odd moments when he assumes you’ll have the same visceral reaction he does, and doesn’t bother to do anything beyond mention the Scary Thing. Which might be angles, or foreigners, or all-devouring entities that care nothing for human existence. King is aware that he’s more frightened than the average person, and has a keen instinct for how to remedy that gap.

“Crouch End” is full of these telling and terrifying details. Some are adapted from Lovecraft. (The warehouse district, incongruity reminding even jaded mythos readers of the strangeness of those names. The bynames of elder gods turned into a child’s street chant.) Some are King’s own. (The unseen horror veiled by a suburban hedge. The thing under the bridge.)

The things that are so effective about “Crouch End” make me even more frustrated by the things that aren’t. King was a staple of my teenage years, when I read him mostly for comfort. Carrie and Firestarter in particular I read as revenge fantasies—high school was not a fun time—while in retrospect they also reflect fear of women’s power, and like Lovecraft fear of what the powerless might do if their state changes. College was a fun time, and as my life has steadily Gotten Better, it’s been a couple of decades since I’ve gone back to this stuff. I regret to report that there have been Fairies.

King’s relationship with sex and sexuality is always odd. I was fine with this in high school, but it doesn’t age well. The ambiguously gay bad cop is particularly jarring, but I could also do without the bouts of intensive male gaze and whining about political correctness. King has narrators who don’t do these things; it’s something he chooses to put in. But all his stories have this background miasma of blue collar resentment, which he writes the same way in rural Maine and urban London. The sameness of the texture, from story to story, grates.

Then there are the things that are less self-conscious, and equally frustrating. Deformity in King’s work always has moral implications, and is always played for maximum body horror. “Crouch End” includes both a cat/demon with a mangled face, and a boy/cultist with a “claw hand.” Surely an author who can make fear taste like mouthwash can make it look like something other than a kid with a malformed limb.

Back to things that work—the degree to which the story’s arc is a movement from disbelief to belief, with belief leading to often fatal vulnerability. This is a more subtly Lovecraftian aspect of the story than the overt Mythos elements. So much of Lovecraft hinges fully on a character moving from ignorance to denial to the ultimate italicized revelation. King’s multiple narrators give us multiple takes on that journey. Farnham resists belief and actively mocks, but is drawn into the “back file” reports and then into the ‘towen’ street. Lonnie has a similar arc, but compressed. Doris survives her vision of reality, but pays it tribute with the little madness of her closet graffiti. And Vetter survives, keeping his head down, right up until he takes that survival for granted by retiring. I guess the Goat With A Thousand Young doesn’t like it when you try to move out of range.

Last thought: Lonnie and Doris’s initial helplessness hinges on the inability to find a cab. Cell phones, of course, disrupt horror; once they’re in place terror depends on lost signal or supernaturally bad cybersecurity. Are smartphone cab apps the next story-challenging technology?

Anne’s Commentary

Stephen King is on the short-short list for writer who best combines contemporary mundanity with fantastic horror. Compared to Lovecraft’s typical protagonists (the scholars, the hunters after the uncanny, the outright revenants or ghouls), King’s characters usually are normal folk. He writes lots of writers, yeah, who might be considered a slightly outre bunch, but plenty of regular folk too, like our unlucky American tourists Lonnie and Doris and our unfortunately stationed constables Vetter and Farnham. Okay, so Vetter’s read SFF. That doesn’t make anyone weird, does it?

Ahem. Of course not.

I wonder how Lovecraft would have written this story. As Doris’s “rest home”-scrawled memorandum or pre-suicide letter, she most likely remaining unnamed? But King isn’t fond of nameless narrators, protagonists or supporting characters. Here we get everyone’s surname at least, except for the weird kiddies (maybe unnameable!), the cab driver (real bit part) and the kitty. We all know the Goat’s real name, right? It’s Shub, for short. My memory may fail me, but King’s also not fond of the found-manuscript form.

Lovecraft might also have centered the story on one of the constables, as he centers it on Detective Malone in “Horror at Red Hook.” King does this in part, using PC Farnham as his law enforcement point of view and ponderer of mysteries. “Red Hook’s” structure is simpler than “Crouch End’s,” for all its plot twists and turns, whereas King’s plot is pretty straightforward, his structure more complex.

We start off in present story time, with the constables after Doris’s departure. King’s omniscient narrator, in the police station sections, stays close to Farnham, preferentially dipping into the younger PC’s thoughts and perceptions. Then we drop back to Doris’s arrival and establishment in the interview room, the beginning of her story, which takes us through “normal” London, where there’s even a McDonald’s. Vetter mentally notes that Doris is in a state of complete recall, which he encourages and which accounts for what’s to follow: Doris’s grisly account, in Doris’s point of view, with lusciously exhaustive detail.

So we have story present, the post-Doris police station starring Farnham. We have story near-past, Doris at the station, where Omniscient Narrator stays close to Doris, with occasional swerves to Farnham and Vetter. And we have story deeper-past, Doris front and center, remembering all that happened in Crouch End. Well, all of it except for her Lovecraftian loss of consciousness and/or memory at the climax of the TERRIBLE THING: She doesn’t know how she got from Crouch End to the “normal” street.

King deftly interweaves story present, story near-past and story deeper-past to heighten suspense and to prevent Doris’s story and Farnham’s puzzlings/fate from becoming two monolithic narrative blocks. Then there’s the epilogue, all Omniscient Narrator, denouement plus ominous closing: It ain’t over at Crouch End, people. It can never really be over at Crouch End. Unless, perhaps, the stars come right and the names on the warehouses manifest to claw the thin spot wide open, unleashing chaos upon the entire planet.

There’s a pleasant thought. Maybe that’s the kind of musing that led to poor Vetter’s heart attack. Imagination’s a bitch. Too little can kill (see Farnham); too much can drive one to debilitating habits, like a daily six (or twelve) of lager.

Strongly implied: Crouch End has a debilitating effect on those who come close. Constables age beyond their years, turn to self-medication, kill themselves. Neighbors shun the place and flee from those who’ve penetrated too deeply, to the Towen. As far off as central London, cab drivers are leery of taking fares to the End, and the one who finally does accommodate the Freemans bails as soon as the weirdness starts manifesting. Unless, to be paranoid, he was IN on the eldritch evil, meant to strand our hapless couple!

And what about this John Squales guy? He LIVES in Crouch End. Could he be unaffected by its alien vibes? “Squale” means “shark” in French. A shark is not only a fish – it’s also a person who swindles or exploits others. Has Lonnie’s work acquaintance set him up to take the place of someone dearer to Squales, a substitute sacrifice to the Towen? The weird kids sure showed up fast when the Freemans arrived in Crouch End. Maybe they were waiting. Maybe they’re the ones who MARKED Lonnie in the first place.

And finally, what about Sgt. Raymond? He breaks pickpockets’ fingers, supposedly because a pickpocket cut his face once. But Farnham thinks Raymond just likes the sound of bone snapping. Raymond scares him. Raymond walks too close to the fence between good guys and bad guys. I bet the boundary between normal London and Crouch End is one of those fences. In the mere line of duty, Raymond must have hopped the fence more than once, absorbing eldritch vibes, exacerbating any natural flaws in his moral temperament, you know, like sadism.

Doris Freeman thinks that the stately manses in Crouch End must have been divided into flats by now. I bet not. I bet there’s not much of a renters’ market in the End, and a high turnover of any renters who might sign leases there. No, you can buy the stately manses cheap and live in them all by yourself. Only caveat: If your lawn starts to moan, ignore it. Also, lay out cigarettes for the cats – don’t make them have to beg. Oh, and if the neighborhood kids wave at you, move out.

Next week, we tackle Joanna Russ’s “My Boat.” [RE: I have no clever quips about this one because I haven’t read it before, and have no intention of spoiling myself for a Russ story just to have a clever quip for the coming attractions.] You can find it in Doizois and Dann’s Sorcerers anthology (available in e-book even), Russ’s own The Zanzibar Cat, and several other anthologies that are mostly out of print.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint in April 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.