Warner Brothers had been trying to develop a Speed Racer film for nearly two decades, but the project never really launched until it was suggested that perhaps the Wachowskis should direct something beneath an R-rating to introduce them to family audiences.

The movie wasn’t very well received, and that’s wrong. Cosmically wrong. Speed Racer is brilliant.

This was the only Wachowski film I hadn’t seen before starting this rewatch (2008 was a busy year). So this was actually a first watch for me, and I had no idea what I was in for. Per instructions from my colleague Leah, I went to Hulu first to watch an episode of the 1960s cartoon for reference. This proved to be useful for a few reasons; I now know the theme song; I had an idea of what I was in for in terms of characters and plots and relationships (the Racer family littlest brother has a pet chimpanzee that he likes to pal around with, for example); I walked in knowing that Speed Racer was an actual name, not some cute nickname or callsign. Having watched that episode, I was considerably more nervous about the film—what about this show could possibly make for entertaining cinema?

About ten minutes in, I found myself shouting: “Why don’t people like this movie? Why don’t I hear anyone talk about it? This movie is AMAZING.” I took to Facebook to demand an explanation, and found that many of my friends love Speed Racer, which gives me hope that it will enter the realm of cult classic sooner rather than later. My most profound reaction was, explicitly: I want to eat this movie.

And when I say that, I don’t just mean wow it’s full of pretty colors and everything looks like candy om nom nom. I mean I literally want to ingest this film and somehow incorporate it into my being, have it leak out through my pores, and then coat the world in its light. I want to feel the way that movie makes me feel every damn day.

I’m pretty sure that’s the highest compliment I can give a movie.

That isn’t to say that Speed Racer is the paragon of cinema, or that it is the greatest piece of art ever produced. But in the realm of uniqueness, there is absolutely nothing like it in American cinema, nothing that even tries. It is cheeseball and violently colorful and blatantly anti-capitalist and so very eager it makes me want to cry. And like every other Wachowski film, it is about love and family and supporting one another and making the world a better place.

Look, I’m not a race car person. I’m also not a sports movie person because they all feel roughly the same to me—the emotional beats all add up to the same peaks and valleys every time. But Speed Racer is a race car movie and a sports movie, and I would watch every sports movie in the world if they were all like this.

Did I mention that the villain was capitalism? Yup.

For the uninitiated, the Racer family is in the car business (through their small independent company Racer Motors), and Speed’s older brother Rex used to be the one who raced family cars in various tournaments. He died in a dangerous race, the Casa Cristo 5000, and Speed took up the family mantle—driving his brother’s old cars, clearly every bit as talented as his brother was. His success prompts E.P. Arnold Royalton of Royalton Industries to take interest in sponsoring Speed, promising to take him all the way to Grand Prix in style and privilege. Speed decides not to take the spot, and Royalton reveals that the Grand Prix has always been a fixed race to help corporate interests, then vows to destroy Speed’s racing career and his family for turning down the offer. Speed is contacted by Inspector Detector of the corporate crimes division, who wants Speed to help him expose criminal activity in Royalton Indutries. Speed agrees, but Royalton does as promised and wipes him out during an important qualifying race, shortly after suing Speed’s father for intellectual property infringement and dragging their family business through the mud.

Speed decides to join the dangerous rally that his brother died racing in because Inspector Detector says it could get him to the Grand Prix—Taejo Togokahn wants him and the mysterious Racer X (who Speed suspects is truly his brother, Rex) on his team for the Casa Cristo 5000 to prevent his family’s business from being bought out by Royalton. Speed’s family is horrified that he’s entered the rally, but choose to stand by him and help. Their team wins the race, but the Togokahn family turns around and simply sells their company to Royalton at a higher price, their true plan all along. Taejo’s sister feels this is wrong, so she gives Speed her brother’s invitation to race in the Grand Prix. Speed wins the race against all odds, exposing Royalton’s racer for cheating in the process and ruining his company.

It sounds simple as can be, but this film is startlingly bright for such a hammer-heavy premise. A lot of that comes down to the cast, who are so earnest in their cartoonish roles that it’s hard to be bothered by how over-the-top everything is. Speed’s parents (whose first names are literally Mom and Pops) are Susan Sarandon and John Goodman, for crying out loud, so there’s really no way that the movie was aiming for jovial mediocrity. Emile Hirsch plays Speed with such a serious brand of goodness that you can’t help but like him even when his character is as Stock Hero as they come. Christina Ricci is so forcefully wide-eyed as his girlfriend Trixie that the strangeness of the character loops back around into a completely enjoyable figure.

This is not a film for the faint of concentration. I can’t help but wonder if this movie didn’t do well initially because it was billed as a family affair, something fun and easy that required little investment. In reality, the plot is awfully complex and so is the timeline. (The very first race we witness flashes back and forth between Speed’s race and one of Rex’s old races, and the integration is so seamless that it can be hard to track, if gorgeous.) If you’re only in the market for mindless action, Speed Racer will not fit the bill.

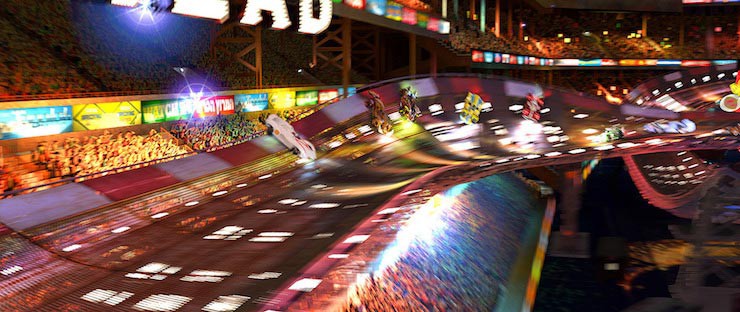

But if you are in the mood for some of the most glorious car racing sequences in film history, go no further. The action in Speed Racer is top notch in every sense, as though everything the Wachowskis worked on in the Matrix trilogy was simply a warm up. The hand-to-hand combat scenes are also a treat for fully absorbing anime stylization into a live-action setting. (I’d argue that it’s better than Tarantino’s work in Kill Bill, if only because the choice to go full camp is beautiful.) This is even more pronounced whenever Speed’s little brother Spritle wants to join the fray—all fights essentially occur in his head, where he can emulate his favorite television heroes. The film also does an excellent job of showing the world from a child’s perspective on more than one occasion, and it prevents Spritle and his pal chimpanzee Chim Chim from becoming an irritating kiddie distraction throughout the movie.

The anti-capitalist commentary is just plain scathing, and it’s great fun to watch. Royalton (Roger Allam, back from V for Vendetta) lands in front of the Racer home in a helicopter, basically invites himself in, and when he tastes Mom Racer’s pancakes, he insists that he wants to buy her recipe. Mom tells him that she’d be happy to give it to him for free, but Royalton is adamant, talking about getting his lawyer to draw up the paperwork. The meaning here is clear—Mom’s cherished, comforting family recipes, willingly given out to appreciative guests, mean nothing to Royalton but capital. He tells her “pancakes are love,” but everything is meant to be exploited, everything exists for potential gain, even that love. When he tries to woo Speed over to his company for sponsorship, Pops makes a point of saying that Racer Motors has always run as a small independent in these races. He gives a sharp line about how the bigger a company gets, the more power it amasses, the more the people in charge of it seem to think that rules don’t apply to them. And Speed, being a good kid, listens to his Pops.

Royalton is every inch the mustache-twirling cardboard cut-out that he needs to be. In a world where we’ve seen how well money and power corrupts on a corporate level, it’s far more enjoyable to view it from the distance that such a comical portrayal provides. But more to the point, it’s jarring when you finally realize that this is an anti-capitalist blockbuster film bankrolled by Hollywood. While it’s doubtful that the studio execs failed to notice, everyone involved still ultimately voted in favor of this angle, and that all by itself is weirdly heartening to see.

The theme of the day is family, and while that is a constant in all Wachowski works, here it is showcased on a more fundamental level. Rather than dealing with the concept of created or found families, Speed Racer is primarily concerned with given ones. This is a story about relationships between parents and children, between siblings and significant others. But rather than making a single-room drama showcasing the complexities of those family networks, the Wachowskis cut it down to essence, to an ideal, and blow it up to marquee size—family are the people who are there for you no matter what. Family doesn’t put you down, family doesn’t make you feel small or less than you are, family doesn’t walk away when you need their support. Family is capable of articulating their failures and working on past mistakes. Family is all you need to succeed.

On the other hand, with parents named “Mom” and “Pops,” these characters are clearly meant as stand-ins for everyone’s family, and they enact those roles at every turn, extending themselves to Sparky the team mechanic, and Trixie as well. It doesn’t come without any struggle whatsoever—Pops takes Speed aside halfway through the film to acknowledge his failings with Rex, and how he plants to do better by giving Speed the space he needs to take his own journey—but this crew never gives up on one another. The Togokahn family is meant as a juxtaposition to this. Yu Nan, Taejo’s sister, has her opinion and efforts repeatedly ignored by the brother and father, resulting in her betrayal when she gives Speed the Grand Prix invitation. She tells him that she suspects he won’t need luck with all the wonderful people surrounding him, continuing to highlight the importance of the support Speed receives from those closest to him.

The film is largely affirming on the theme of identity. The entire plot revolves around Speed coming to understand his legacy as a racer, one that heralds from his family and has defined him his entire life—the opening sequence features Speed as a little boy, unable to concentrate on a test in school as he imagines himself behind the wheel of a race car in his own technicolor cartoon world. We come to understand that the death of Speed’s brother has ultimately held him back from his destiny—a desire to respect Rex’s career as a racer has made Speed hesitant but also humble. He needs a push to recognize that he deserves to embrace this part of himself. But the best part of this legacy? There is no true “greater” meaning behind it. Speed simply loves to race. It makes him happy, it drives him, it means something more than track and wheels and awards. That’s good enough.

But there is one place where the question of identity takes a sharp and sad turn, particularly for a film filled with so much color and joy. Racer X is eventually revealed to be Rex after all; in an effort to protect his family while he took on the corrupt racing world, he staged his own death and had massive plastic surgery. When Speed finally confronts Racer X about his suspicions regarding his identity, he cannot recognize the man, and Racer X tells him that his brother is definitely dead. By the end of the film, Inspector Detector asks him he made a mistake, leaving his family, never telling them that he’s still alive. Rex’s reply is simply: “If I did, it’s a mistake I’ll have to live with.”

It’s hard to dismiss the idea of Rex’s changed physical appearance being something that bars him from returning to his family. It’s hard to dismiss that although they win the race and expose the corruption, although they win the day, Rex still doesn’t believe that he can return to the people who love him. It’s the one true moment of pain in the entire film, and it’s impossible to ignore the fact that it deals with a character who has essentially transitioned into a new person.

All of these themes and thoughts come together in the no-holds-barred phantasmic explosion that is the Grand Prix. Like I said, I’m not a fan of sports films in general, and the “final game” is a thing with very specific beats and shifts—I expected to get bored at this point. But as the race commenced, my eyes only grew wider and wider.

The theme song suddenly wove its way into the soundtrack:

Go, Speed Racer!

Go, Speed Racer!

Go, Speed Racer, go!

I could feel myself grinning hard enough to make my cheeks ache. Big bang action sequences that make up the end of movies are anxiety-filled affairs; we love to watch them, but the experience isn’t typically pleasant in the truest sense of the word. We endure them. It’s what we pay for enjoying those sorts of high-octane thrills.

Go, Speed Racer, go!

That anxiety was completely missing as I watched the end of this film. Instead I felt the strangest emotion come over me in its place: Delight.

It doesn’t matter that you know Speed has to win, it doesn’t matter that that you’ve seen dozens of car chases and races in all across the big screen, it doesn’t matter that you’re accustomed to feeling cynical at these sorts of stories. Like I said, I want to eat this movie. I want it pumping through my veins at all times. I want to feel exhilarated just by walking down the street, like I’m driving the Mach 5.

Who wants to live in a perfect rainbow with me?

Emmet Asher-Perrin will be singing that theme all week. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.