On a cool evening in Kolkata, India, beneath a full moon, as the whirling rhythms of traveling musicians fill the night, college professor Alok encounters a mysterious stranger with a bizarre confession and an extraordinary story. Tantalized by the man’s unfinished tale, Alok will do anything to hear its completion. So Alok agrees, at the stranger’s behest, to transcribe a collection of battered notebooks, weathered parchments, and once-living skins.

From these documents spills the chronicle of a race of people at once more than human yet kin to beasts, ruled by instincts and desires blood-deep and ages-old. The tale features a rough wanderer in seventeenth-century Mughal India who finds himself irrevocably drawn to a defiant woman—and destined to be torn asunder by two clashing worlds. With every passing chapter of beauty and brutality, Alok’s interest in the stranger grows and evolves into something darker and more urgent.

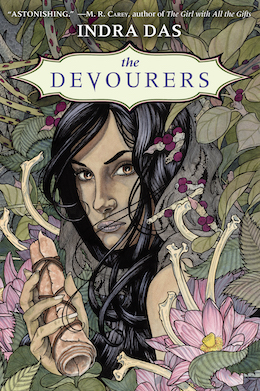

Shifting dreamlike between present and past with intoxicating language, visceral action, compelling characters, and stark emotion, Indra Das’ The Devourers offers a reading experience quite unlike any other novel. Available July 12th from Del Rey.

A new day. I take the metro, emerge at Park Street station, and walk down the street to Oly. Park Street is the Times Square of Kolkata. Any devout Kolkatan will tell you this. That doesn’t mean it’s anything like Times Square, of course. But for a quiet man like me, it’s enough. It’s not as if I have a lot of friends to go bar—hopping and dancing with, or anything like that. So if you haven’t been there already, imagine a wide street (well, compared with the usually narrow streets of this city), adorned with restaurants and stores and coffee shops and stalls and bars that have barnacled the smog—stained remnants of colonial British architecture. Add more recent buildings that stand shoulder—to—shoulder with these reformed mansions, and fill the whole place with people. That’s one thing Park Street does have equal to Times Square—people. On the street walking side by side with passing cars, on the pavement rubbing shoulders like the buildings around them. They’re everywhere, as you would expect in one of the most densely populated areas of the planet.

I am there, on Sunday, in the twilight that forms between the buildings of cities when the sun is too low to shine directly on the asphalt. The streetlights have come alive, but day still clings on. I’ve lived here so long, but meeting someone who claims to be more than human makes me see everything differently, like at the dhaba last night. My eyes linger on every street dog, curled by the passing feet of pedestrians or exploring the footpaths, so different from their predatory nocturnal incarnations. But more than the dogs, it’s the people, the city that suddenly seems strange, yet not strange enough. Everything feels like a comedown from a trip, an intense high—so much so that it’s physical, a headache growing behind my skull and promising to break at the notes of the stranger’s voice.

I keep to the footpath, avoid the streaks of odorous water and garbage clotting the gutters. Steamy food—shacks offer passing clouds of warmth from winter’s chill, the heat of open—air cooking trapped under blue plastic tarpaulins stretched over the sidewalks to shelter their customers. I pass hawkers selling snacks, sachets of supari, cigarettes, perfumes and colognes, pirated movies, discounted books and magazines, condoms both imported and not—all operating right beside less ephemeral retail outlets and eateries with glass walls that look into different worlds.

Everywhere, the behavior of our different packs and clans and tribes on display. Beggars hover close to the transparency of storefront windows in the hope of absorbing some of the opulence within. I pass the well—lit glitz that hovers around the entrance to Park Hotel and its fashionable discos and restaurants, edging by young men and women emerging from chauffeured cars, bodies musked with cologne. I’m careful not to touch any of the girls by accident (I hesitate to call them women), as I don’t want to attract the ire of their well—groomed male companions. A pimp, probably on the lookout for hotel patrons, asks me in flamboyant English if I’d like to spend the night with a college girl, and I shake my head and keep walking. Not too far from there, I reach the popular refuge of the firmly middle classes, Oly Pub. It looks plain and weathered next to the higher—profile stretch of pavement real estate by the hotel, though the building does hint at a faded grandeur. I make a quick supper of a chicken and egg roll at Kusum’s Rolls and Kebabs right next door, and head into the pub.

I nod to the doorman who probably recognizes me, and duck into the fluorescent—lit gloom. I go upstairs to the windowless sanctum of the air—conditioned section, hoping that the stranger will also go there. A cigarette haze hangs over the Formica tables, as if the winter mist has followed me inside.

I search the faces in the room till a waiter gives me a grumpy glance, pointing out the fact that I’m standing in the middle of the carpeted thoroughfare without saying a word. The stranger isn’t here. My aching head feels heavier at his absence. Though it’s still light out, Oly is already crowded. I find a table in the corner and order a whiskey double with water, hoping it will calm the headache. The same waiter brings me the drink and takes a while doing it. I bide my time, sipping my watered whiskey and nibbling at the pile of dirty—yellow daalmoot in the little plastic plate by my glass, feeling more and more guilty for taking up an entire table all by myself while the pub fills up.

But he does show up.

He appears by my table without warning, half an hour later. It looks like he’s wearing the same flimsy kurta and worn jeans he wore yesterday, and his hair tumbles down to his shoulders again, the ponytail he left with last night abandoned. He’s carrying a dusty blue—and—black JanSport backpack that makes him look younger. Like one of my students, except for those quivers of gray in his hair.

“Professor. I trust you weren’t waiting long?” He takes off the backpack and slides it under the table with one foot. He’s still wearing those sandals.

“Oh no. I was just, you know,” I say.

“Waiting?”

“Yes. No, I mean, it hasn’t been that long. Please, sit. Thanks for coming.”

He pulls up the chair opposite and sits down. I blush, and am thankful for the smoke and dim lighting. I get the feeling that he knows I’ve been waiting a long time and likes it. Nervous sipping has almost emptied my glass of whiskey, so I feel tipsy and inclined to forgive him. I’m just glad that he actually showed up, and more grateful than I feel comfortable being. The sound of his voice is an uncanny placebo for the throb behind my eyes.

“Would you like a drink?” I ask.

He nods and waves his arm. To my amazement, the waiter shows up immediately. He isn’t any less grumpy, but I’ve never been able to make a waiter at Oly Pub show up in fewer than five minutes. The stranger orders two whiskey doubles. I feel flattered, both by his taking the liberty to order me another and by his appropriation of my choice for his own drink. I have to stop myself from thanking him again.

“The haunt of heroes,” he says, leaning back and looking around. I assume he’s referring to the pub’s original—now truncated—name, Olympia.

I wonder how to respond. The stranger folds his hands on the table and looks straight at me, making eye contact. I have no idea what to say to him, what we’re going to talk about, how to start a conversation with him, why in hell I even wanted to meet him again.

“Did you keep the kitten?” I ask him.

“I ate it.”

I stare at him.

“A poor joke. Forgive me and pull down your eyebrows. The kitten’s safe, with a saucer of milk all her own. She’s taken quite a liking to me. Or perhaps just to not being terrorized by stray dogs.”

“I’m glad you kept her.”

“So here we are, and you still haven’t told me your name.”

“Oh. I’m sorry. I’m Alok. Alok Mukherjee.”

“I’m very pleased to meet you, Alok,” he says and licks his teeth. There’s something fidgety about him today, not like the calm of that old half werewolf I met yesterday.

“What’s your name?” I ask, after waiting awkwardly.

“Professor—you don’t mind if I still call you Professor, I hope—my name hardly matters.”

“Why’s that?”

“You haven’t been listening.” The refusal to play his part in this human ritual disturbs me. The waiter appears with his bottle of Royal Stag, a glass, and his bronze peg measure, and pours us both doubles. I wait.

“What should I call you, then?” I ask the stranger once the waiter’s gone. The rims of our glasses meet sharply.

“You can call me anything you want. Anything at all.”

I find this an unwieldy suggestion. “Are you still saying you’re part werewolf?”

“Isn’t that why you wanted to meet me again? To find out more? Alok,” he lilts. “What do you want to know?”

“I—I don’t know.”

“I’m aware of that. I’m asking what you do want to know.”

“I know what you’re asking,” I tell him, irritated. For all his effort to project immortal wisdom, there’s something childish about his way of engaging with me. I look into my glass. “You’re interesting. That’s why I—” I clear my throat. “That’s why I agreed to meet you again.”

“How kind,” he says.

“I want you to finish the story you started yesterday.”

“Ah. Professor.” He leans forward, placing his elbows on the table.

“You’re clearly an intelligent man. I want you to know that. I’m not trying to best your intellect with an elaborate prank here.”

“That’s good, I guess. You don’t have to keep calling me Professor.”

He smiles. “I find you interesting, too, though you might not believe it. We’re not the same at all. We’re not even close to the same age. But if we’re to talk like adults, you’re going to have to take a leap of faith that quite frankly isn’t possible for a human being in this day and age, not one in your social and environmental circumstances.”

“You’re telling me I’m going to have to believe whatever you say,” I say.

“You don’t have to believe me. But you’re going to have to act like you do. For the sake of this play we’ve both walked into. You agreed to be in it, yesterday night. If you abide by that agreement, we can talk.”

“And why do you think I’ll do that?” I ask.

“Because you followed me out of the mela. Because you came here today,” he says.

I nod slowly, unable to refute that. “Okay. Why are you here, then?”

The stranger takes a drink. “Yesterday I told you stories. You called it hypnotism. Say it is that. Say I’m hypnotizing you. That it’s an illusion. A magician still needs an audience, doesn’t he.”

“If you’re that good a magician, why find one person in a crowd. Why not charge people, fill an auditorium.”

“Because that would be tawdry. Sometimes intimacy is the only way real magic works.”

“Intimacy,” I say, and rub my forehead. “I don’t know your name.”

“Get out of here, then,” he says. I look up. “You’re not my prisoner, Professor Mukherjee, and don’t pretend that you are. Leave, if you think the only way to achieve intimacy is dry custom, the exchange of facts and labels, names and professions. Intimacy lies in the body and the soul, in scent, in touch and taste and sound. A man whose name you don’t know can tell you a tale to move you to tears, just by filling and emptying his lungs, by moving his tongue and lips, his fingers. Even after, you might never know him.”

His voice doesn’t rise. But I feel my heart beat faster, my headache thumping with it. I look at my unsteady hands, relish the whining note of my headache.

“Tell me something. Are you going to ask me for money after the evening’s done?” I ask.

“No. I’m not a hawker.”

I put the glass of whiskey and melting ice against my forehead.

“Magicians don’t work for free.”

“Metaphors only go so far. I’m not a magician, either. Just tell me, Alok. Do you want to hear more? You wanted to, last night. Do you still want to?”

I close my eyes, feel moisture trickling off the glass and down my head. I nod.

“You’re more open—minded than most historians, then?” he asks. I open my eyes.

“Again with the generalizations. I’m not even sure where you got that one from.”

“Very well. For one thing, I’m not going to finish the story I told you yesterday.”

“Why not?” I ask.

“Because it’s not important right now. It did what it was supposed to, and it’ll come back when and if it needs to.”

His face goes vacant as he looks at one of the resident rats of this dank Olympia. It scampers between the tables, darting over the crimson carpet and looking for crumbs to scavenge, unafraid of the many human feet around it. I remember the dead rat by the stranger’s feet last night. The stranger looks young again, unlike yesterday night after he finished the stories. The unruly hair, the smirk. The familiar combo of jeans and kurta. For a second I think that maybe he actually is one of my students, playing an elaborate joke to humiliate me once it gets out on campus. That I’ve somehow failed to notice him in my classes, or failed him, and this is some kind of revenge.

“What did you do to me yesterday?” I ask, if just to stifle this thought.

“What you saw or felt has its provenance in your own head.”

“It’s absurd that you would even say that, after introducing yourself in the way you did. And it’s not like I’ve never been told a story before. I felt something else. Like—” I stumble on the word, but force it out. “Like magic. Like you said.”

He waits, as if for me to make a point.

“I’ve honestly never felt anything like it in my life. It felt like you shared a bit of lost time with me, shared the memories of something that can’t—shouldn’t—exist, like you had it hidden under that kurta of yours and just, I don’t know, gave it to me.”

A flash of teeth. “How eloquent.”

“You’re being facetious, but it’s true. The more I think about it, the more I feel that you did something impossible yesterday night. If it’s a trick, it’s one I’ve never seen or heard of before.”

He is silent for a moment.

“Well, Professor, I’m glad you liked my ‘trick.’ I have something to give you,” he tells me.

He takes a gulp of his drink and pulls a large, mustard—yellow manila envelope out of his backpack. He places it on the table. I notice that his glass is almost empty already.

“You want to know more. Here is something more,” he tells me, one hand on the envelope.

“What is this?”

“This is history. History most people—humans—aren’t aware of, in particular. As a professor of history, I thought you might appreciate that.”

“Can I open it?”

“Of course. I brought it here for you.” He removes his hand from the envelope. I take it and open the flap to look inside. It’s a plain black hardbound notebook, filled with slanted handwriting. Black ink and the smudged gray of pencils. From the first to the last, the pages (which have no lines on which to write, though the penmanship is straight and true) are crammed full. I catch fragments, written in English. In the middle, I find the skeleton of a leaf, which wisps out to float to my lap. I pick it up and put it back in the notebook.

“You want me to read this?” I ask.

“Yes. Take it with you,” he says.

“What is it?”

“I suppose you could call it a journal, from another time. A voice from the past.”

“Whose voice?” I ask.

“You’ll find out when you read it.”

“This is because you say you’ve—because you’ve lived a long time. That’s why you have access to this?”

“Yes,” he agrees.

“This doesn’t look very old.”

He smiles. “Very observant. I translated them from the original source. I doubt you can read the languages the source contains. Either way, I can’t just go around giving historical artifacts to strangers, can I?”

I’ve tended to think of him as the stranger. I am a stranger to him. But I can’t shake the feeling that he somehow already knows more about me from two conversations than many of my alleged friends do. Even family, why not. More than I could ever hope to know about him.

“You’re a translator? Is that your job?” I ask him.

“I translated what’s in that notebook you’re holding. That doesn’t make me a full—time translator.”

“So I take your word that this notebook contains a journal from another time. Because, for some reason, you took up translating as a hobby.”

“Lord above. You don’t have to take my word for anything. Just pretend if it’s easier. Read what I’ve given you and see what you think. Decide for yourself. No humans—well, that’s not true. Very few humans have read what you’re going to in those pages. This is just a part of what I can give you. There’s more.”

“So why are you giving me this?”

“I want to hire you. To transcribe these documents, type them out.”

“But I’m not a transcriber. I just teach history. I write essays. Nothing like this. You should get a professional.”

“Do I look like I want a professional? You’re a student and teacher of history, Alok. That is enough. I’m giving you an opportunity that very few historians could even dream of. It’s a simple request. Type out what you read. That’s all. I’ll pay you.”

“And the sources? Do I get to see them? The actual historical documents. Surely you realize that if you actually have such things, I’d be very interested in seeing them, rather than this. I am a historian, after all. What period is this from? My specialization is late modern, colonial India mainly, but obviously, I’d be interested in any kind of text from the past.”

“You might well see the original texts. If you prove yourself interested enough. Worthy of it. Just read the translation first. It might tell you a little more about what you want to know about what I am.”

“A werewolf,” I say, to pin him down a bit.

He licks the rim of his glass. I clench my jaw and look away, catching a glimpse of his tongue sliding wet from between his lips.

“Half,” he says. He drains the last of his drink. I have much of my glass still left, despite drinking fast to keep up with him. He hasn’t denied what he claimed yesterday, but he hasn’t been embracing it, either. And now he’s hired me to do a job. It feels odd, even mundane. But I can hardly forget what he’s proven himself capable of. The thought of historical journals describing werewolves in the past does excite me, coming from this particular man.

“I’ll do it,” I say, and take too large a gulp of whiskey.

He wipes his mouth with the back of his hand. “Good,” he says, and tosses some hundred—rupee notes on the table. Enough for both our drinks and tip. The opposite of demanding payment from me.

“You’re leaving?” I ask.

“We will meet again,” he says, snatching the backpack from under the table and slinging it onto his shoulders.

“Right. But. Where will we meet again?” I ask before he can hurry off.

He gets up and stops, looking distracted by my question.

“Do you have a phone number or an email address? Some way we can get in touch?” I suggest, to help things along.

“No. But I will see you again. Goodbye, Professor Alok Mukherjee. Thank you for accepting this task.”

He walks away so quickly that I’d assume that he has an emergency to get to, if not for his calm. I don’t have the time to ask how he’s going to get in touch with me. I suppose I can call out before he disappears through the new patrons standing and waiting by the stairwell door for tables. But I don’t.

I feel both excited and disappointed. I had expected more. To be hypnotized again like last night, away and out of my current body in this present. The headache remains.

Perhaps what he’s given me will do as a substitute, for now. I double—check the pages of his notebook, to make sure that they actually have words on them, that they’re not just a bunch of scribbles on paper. There is a line of poetry written on the inside of the front cover in pencil, small but visible. It’s Blake, though I’ve forgotten what it’s from. Seeing it reassures me. I feel drunk. Confident despite it all that I will see him again, just like he said. I shake my head and look around, to see if anyone has noticed what’s transpired. But nothing has transpired, nothing that can be seen by anyone other than me. No one is looking at me. I have a whiskey to finish, alone. I start reading.

First Fragment[i]

This new parchment I write on is fresh skin:

Taken from the back of a boy we found wandering alone near the dusty walls of Lahore, weeks after we crossed the borders of the Mughal Empire and days after we swam across the silt—clouded waters of the Indus. I took the child by his warm brown arm and spoke into his ear in Punjabi, asking him, “Where are your parents?” and he answered in a wet voice, “They have sickened and died,” and I slipped my thumbs under the curve of his jaw to feel him live before I bent his neck and broke it so he cried no longer (some have said I take to pity too easily). I hold him now in my hands, his skin toughened under the sun of his empire that forgot him and over the smoke of our campfires burning earth—fed wood.

Not a league from the child’s killing we found his mother lying on the ground, clothed in flies. There was a newborn babe clutched in her arms snaked in purple umbilicus. The woman’s thighs were scabbed in the sun—dried crust of the infant’s birth, her stomach still flaccid from its expelled weight. The babe sucked at her cold nipple. It hurt me to see the bravery of this female, striving to feed her offspring moments before her death. I did not tell my companions my thoughts. I lingered a moment longer, to bless the female and her babe with remembrance. How many times have I witnessed such sights across the centuries, and willfully ignored them?

Makedon dashed that cherub’s head with a rock. A small mercy that he did not play with it. Gévaudan stared at the pitiful sight with a grimace of disdain. We did not eat of mother or infant, for our fardels[ii] were full at the time, and we were in no mood to scavenge like wild dogs, having trekked long to reach Lahore. We went on, to let them rot or become food for lesser creatures than us. I sought some comfort on her behalf, for the fact that her older son lived on in some way inside us, in the weird metabolisms of our shifting selves, in our dreams of his young life.

I test the scroll I made from him here, this dried skin to clothe the flesh of a story, or many. It holds under the bone of the nib.

In Mumtazabad:[iii]

I saw you. You of human men and women, you of one self and one soul. I cannot tell you that you shone out to me first. There were many men and women and children who kindled my appetites in Mum-tazabad, where the workmen dwell and the travelers in Shah Jahan’s empire may rest in caravanserais and barter in bazaars. I saw them everywhere, these virgins and sodomites, scented with dusty sweat and the stains of their exploits. Men with gray eyes and drought—cracked lips who prostrate themselves to their Allah, unaware of wolfish eyes that fall upon their upraised buttocks. Peasants male and female, naked but for plain loincloths grown damp, dark skin glazed with sweat from their toil, even in winter’s chill. Noblemen lounging in shaded palanquins, mouths red with chewed betel, their salwars and breeches threaded with winter sun. Noblewomen in peshwaz robes, muslin waves that ripple like curtains at their windows, their veils brushing lips only glimpsed through fabric, powdered talc clinging like frosts on the downy slopes of their cheeks. So many succulent lives, churning with diverse energies, waiting to be tasted.

Yet I chose you. The sun was at its zenith when we entered the caravanserai, walking behind the odorous camels of a traveling merchant, and as the bleating animals parted and we came into the open courtyard, I saw you leaning against a pillar playing with your oiled curls, mouth sliced by the shadow of your nose. You looked at me, stared at me and my companions clad in strange furs and tunics so foreign, and your eyes seemed to me like no eyes I had ever seen north of the Indus. Yes, you looked at me and I wished you were not human, that I could cleave your soul in two and watch your second self emerge, a beast as lovely as your first.

I walked up to you and you stared still, chipped nails grasping those curls and twining them ’round your fingers. Your eyes, planets of shallow sea shaded by your unpowdered brow, eluding all colors, so gray and blue that they ceased to be either and seemed to me green, as the eyes of our second selves often are.

“What do you want, foreigner?” you asked me.

“As a foreigner, I want to talk to one who isn’t foreign to this land,” I said, and relished the surprise on your face as I spoke back to you in Pashto. But even as surprise sweetened your expression, you did not avert your gaze.

“Then keep moving. I wasn’t born here but in Persia, and some here might think me a foreigner, though my mother brought me here in her arms when I was little.”

“Would you believe it if I told you that I can’t remember where I was born?” I asked you.

“I would not.”

“Fairly answered. Still, it’s true. That would make me a foreigner the world over, wouldn’t it?”

“It would.”

“Then it matters little where I am and where you are, because wherever I might meet you, I’ll still be a foreigner and you less so.”

“A feeble argument based on an impossibility,” you said, fiddling with your hair again. You looked around, peering behind me.

“Where are your foreign friends, then? We don’t often see men so heathen in appearance, no one can tell which part of the world they’re from or what gods they hold true. And such devilish—looking folk even less so.”

“Each of us is from a different place, and many places. I apologize, my lady, for our raiment, which is made from wild beasts and might lend us a disposition similar to them.”

“I’m not so easily offended. There are more frightening men than you and your companions here in this sinkhole of a bazaar, not to mention this empire, despite your looks.”

“You might be surprised,” I said, and you seemed off—put by what seemed like a boast, but was merely the truth.

“So where have your friends gone?” you asked.

“To wash themselves in the baths.”

“And you alone among them thinks keeping the stink of travel on you is attractive?”

“Your tongue is sharp. You might be thankful that I don’t follow the customs of man in treating his woman.”

“I’m not so easily thankful, either, traveler. If I offend you, take your leave.”

“Like you, I’m not so easily offended, my lady.”

“And you shouldn’t be, looking like you do. It’s sensible that you should look like a beast, if you don’t follow the customs of man as you claim. Where are you from?”

“I don’t remember. And I have ranged far and wide since that unremembered birth. But I came here with my companions from the gates of a city called Nürnberg. From another empire, like this one, but for the people of Europe, known sometimes as the Holy Roman Empire.”

The mask of your wariness seemed to slip a little. “You’ve traveled far for one with no camels or horses. You must be very tired.”

“I’ve had enough rest. Tell me, why is a young woman sitting here alone in the middle of a caravanserai? Why is your husband or suitor right now not at my neck with a blade for talking with you?”

“I let whatever suitors come my way pay for my travels, after which they slip from my sight and are never seen again,” you said.

“And if you are not wed, why are you not in the company of other women, and covered? Surely you are Muslim, if you are from Persia,” I said.

“Muslim I may be, yes, but I’ve no husband, nor family, nor home to stay in. My modesty matters little to anyone—I’ve as little need for covering myself as any Hindu commoner you see on the streets.”

“That is unusual.”

“Is it? Would that I were lucky enough for the privilege of purdah. Sounds like paradise to me. If you like, you can call Shah Jahan’s guards to drag me to the nearest harem for your pleasure. Perhaps that would suit the eyes of a white man better than seeing a Muslim woman uncovered?”

“I’m merely curious, my lady. Even with the vast knowledge I’ve gathered of your kind and its various peoples, I sometimes get confused.”

“My kind.”

“Khr—that is, humans,” I told you, strangely unafraid of revealing myself.

“It’s told white men are arrogant, but this is new,” you said, puzzled.

“And where are you traveling?” I asked.

“Your fellow white men land on our shores to the west, and now to the east as well. Perhaps they’ll have work, or ships to carry me to other lands,” you said.

“See the worlds.”

“The world. Yes,” you said.

“A strange inclination, for one of your position and sex.”

“Is it?”

“So I supposed. My friends will return soon, and we’ll be leaving here, once I’ve washed myself also at the bathhouse.”

“Then what is it you want, if you’re not staying? Get to it.”

“These are gold coins from Europe, and more currency from this empire,” I said, and gave you two crowns from a dead Frenchman’s pocket, two silver rupiyas, and two golden mohurs.

“What do you want for this, if not to lie with me?” you asked.

“I want a lock of your hair.”

“Why?”

“A jewel, if you will, for me to wear around my neck for the rest of my journey. This is a town of bazaars, and you offer your body, for a night or a span of noon, to travelers who yearn for the company of women. I ask for a minute portion of your body to keep for my own forever, rather than the whole for an hour.”

“You want only bits of my hair for these coins?”

“I swear it.”

“It’s done,” you said, and pulled a cascade of curls from behind your ear, and before I could offer you my Pesh—kabz,[iv] you took a thin thread of hairs and placed it between your teeth, and with a wrench of your neck you severed three inches from yourself, deft as a seamstress dividing the string. Quick in my shadow, so no one would see. Your teeth were sharp stones dulled by civilization. You tied the lock into a circle and gave it to me, a knot of yourself in my hand, damp still from your strong bite. In my hand, your dead self, your spit, your skin, for a few coins in yours.

“One question, foreigner. How do you speak my language so well?” you asked.

“A dead man taught me, after I ate him, just as the Christ taught his disciples the love of their God after they ate him.”

“You’re a strange people, you white folk. But your dead man taught you well.”

“Yes. He had little else to do, once he was in my stomach. I thank him every day for making my travels through your land easier.”

“And I thank you for the coins. Farewell, foreigner,” you said and walked away, unaware of the value of our transaction, unaware that I held you in my hand as a wolf holds a crippled hare under its great paw.

[i] The stranger divides the translation into two fragments, which I assume are pieces of the original scroll mentioned within the text. His handwritten text has no real divisions, though I’ve remained faithful to his paragraph and line breaks. I attempted some formatting of my own by dividing the two fragments further into sections where it seemed appropriate.

[ii] Archaic term for a bag or bundle.

[iii] A town built during Mughal emperor Shah Jahan’s reign to house the large number of workers building the Taj Mahal. Later it was also called Taj Ganji.

[iv] A type of dagger originating in the region now known as Iran, in the seventeenth century.

From the forthcoming book The Devourers by Indra Das. Copyright © 2015 by Indrapramit Das. Reprinted by arrangement with Del Rey, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.