Over the years, just about every form of media has been translated into prose. There have been novels and short stories written about composers, classical and jazz musicians, rock bands, films, plays, paintings, and sculpture. Some accurately and deftly channel the artistic discipline at their heart; others come up short, resorting to clichés or revealing a fundamental flaw in the author’s understanding of how the medium in question works. Novels that incorporate comic books into their plotlines are no different. At their best, they can make readers long for a creative work that never existed in the real world. When they’re less successful, they come off as discordant—the superhero or science fiction or fantasy narratives that they recount read like works that would never have been published in the real world.

In recent years, Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay has set a high standard for other books to follow. In telling the story of two cousins who create a World War II-era superhero, Chabon was also able to touch on questions of religion, culture, inspiration, family, sexuality, and more. A key question for any fictional comic book is that of plausibility. Some writers opt to create thinly disguised analogues of iconic superheroes—and given that homages to the likes of Superman and Batman are already widespread in many a comic book continuity, this isn’t exactly an unheard-of narrative move. But it can also be problematic: if your fictional superhero seems like Wolverine or The Flash with a slightly different costume, the effect can be one of pastiche, diminishing the creative work done in the novel as a whole.

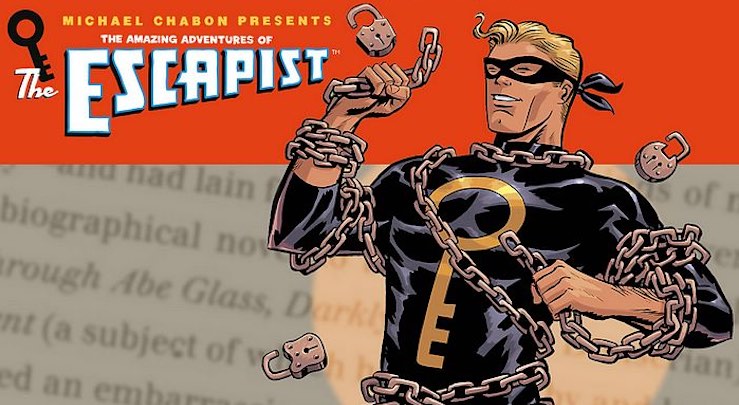

Chabon opted for something trickier: a superhero who would be believable as a product of the same time period wherein pulp heroes like The Shadow gave way to the likes of Batman, but would also not feel like too overt an homage. Thus, the character of The Escapist was born—a superhero with a talent for escaping from dangerous situations. And in Chabon’s telling, this felt just about right: The Escapist seems like a product of that era; if one somehow produced an issue of The Escapist from the early 1940s, many readers would not be shocked. The Portland-based publisher Dark Horse Comics, in fact, ran a series of comics featuring The Escapist, along with The Escapists, a spinoff about comics creators in the present day tasked with reviving and revising the character.

A different approach is taken by Bob Proehl in his novel A Hundred Thousand Worlds. Among the characters that populate his novel are a number of writers and artists, some working on critically lauded and creator-owned titles, others working for one of two rival publishers of superhero comics. There’s plenty to chew on here, including riffs on Marvel and DC’s rotating creative teams on different books, sexist narrative tropes in superhero comics, and the often-predictable way that certain creators move from creator-owned titles to flagship superhero ones. One of the two rival companies is called Timely, which readers with some knowledge of publishing history might recognize as the predecessor to Marvel Comics; another smaller company is called Black Sheep, which reads like a riff on Dark Horse.

These riffs on existing companies fit into part of a larger structure: the tale of drama amidst comics creators is established as parallel to the story of Valerie Torrey, an actress, and her son Alex. Previously, Valerie was one of the stars of a cult science fiction television show, Anomaly, whose stories of time travel, long-running mysteries, and unresolved sexual tension echo Fringe, Quantum Leap, and, most especially, The X-Files. (Valerie’s co-star, also Alex’s father, followed that up with a show that sounds not unlike Californication.) That larger structure makes a particular corner of storytelling one of the main subjects of this book: Valerie recounts the plots of Anomaly episodes to Alex, and Alex in turn talks with one of the artists in the novel’s supporting cast about making a comic. And one acclaimed independent title, Lady Stardust, about a woman whose beloved is cycling through a series of alternate identities, who must be killed one by one, sounds weird and strange and deeply compelling–if Proehl ever followed Chabon’s lead and turned his fictional comic into a real one, I’d be eager to read it.

There are other nods to comic narrative devices found throughout the novel: the phrase “Secret Origin” turns up in a few chapter titles, the structure of the book name-checks different eras of comics, and one of the book’s epigraphs comes from Grant Morrison’s metafictional Flex Mentallo: Man of Muscle Mystery. (Another comes from Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, which is also referenced frequently.) Proehl’s novel is saturated with adventure comics, but it’s also interested in how those comics fit into a larger cultural context.

Comics play a very different role in Benjamin Wood’s The Ecliptic, the story of a troubled artist, Elspeth Conroy, making avant-garde work in 1960s London. Late in the novel, Elspeth encounters a number of issues of a comic of unclear origin, focusing on a character trapped on a mysterious vessel. “[T]here’s no way off it, not that I’ve ever found,” the villain tells him at one point. This comic is intentionally oblique: the issues that Elspeth discovers have been damaged, and thus she’s working from an incomplete version of the story. But given that this fragmented, surreal story is nestled within a fragmented, surreal story, that seems appropriate. It’s also a telling flipside of Elspeth’s own background in fine art–though some figures do overlap in those worlds (Gary Panter comes to mind), pulp comics and conceptual art are generally far removed from one another.

Comics as artifacts turn up in a more fleshed-out form in Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven. The novel is largely set in a North America several years after a devastating plague has decimated civilization as we know it. Much of Mandel’s novel focuses on how aspects of culture are preserved: many of the novel’s characters are connected to a traveling theater group that performs the works of Shakespeare. The novel’s title, however, comes from a different source: a comic book about a scientist who, a thousand years from now, evades the aliens that have taken control of Earth “in the uncharted reaches of deep space.” His home is Station Eleven, and the story of how this comic came to be, and how it survived the downfall of life as we know it, is one of several narrative threads in Mandel’s book.

There’s a sense of the holistic to Mandel’s novel, which is meticulously structured as it nimbly moves through several perspectives and points in time. As in both Wood’s novel and Proehl’s, an adventure comic is juxtaposed with a more traditional idea of high art. (The same is true of Chabon’s, where Salvador Dalí makes a brief appearance.) In the case of Station Eleven, perhaps the most aesthetically expansive of all, the comic within the novel becomes something to hold on to: the reader sees its creation, and thus feels a sort of kinship with it, just as the characters fixated on it do.

The comic books featured in these novels occupy a wide stylistic range, from familiar-sounding superheroes to excursions into intentionally ambiguous spaces. But these fictional comics also tell compelling stories in their own right, and add another layer as well: echoing the ways in which we as readers find ourselves drawn in to this particular form of storytelling.

Top image from Dark Horse Comics’ The Escapist #1; art by Eric Wright.

Tobias Carroll is the managing editor of Vol.1 Brooklyn. He is the author of the short story collectionTransitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the novel Reel (Rare Bird Books).