Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

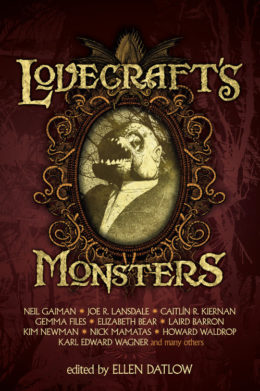

Today we’re looking at John Langan’s “Children of the Fang,” first published in 2014 in Ellen Datlow’s Lovecraft’s Monsters collection. Spoilers ahead.

“When they were kids, Josh had convinced her that there were secret doors concealed in the walls, through which she might stumble while making her way along one of them. If she did, she would find herself in a huge, black, underground cavern full of mole-men. The prospect of utter darkness had not troubled her as much as her younger brother had intended, but the mole-men and the endless caves to which he promised they would drag her had more than made up for that.”

Summary

NOW (in story time): Rachel enters her grandfather’s basement. The remembered smells of mildew, mothballs and earth linger. The sounds of furnace and settling house, the feeling the basement is larger than the house above, the same. As for the look of the place, it’s a dark blur that Rachel navigates with a cane. Considering her mission, could be just as well she can’t see.

THEN: Rachel and younger brother Josh live in Grandpa’s house with their parents. The second floor’s exclusively Grandpa’s, all entrances locked. Also locked is a huge freezer in the basement. Did Grandpa bring back treasure from the Arabian oil fields? If so, why does it have to stay frozen? And why does Grandpa, long retired, still travel extensively to China, Iceland, Morocco, Antarctica?

Teen-aged Rachel and Josh discover audio tapes in an unlocked attic trunk: recorded conversations between Grandpa and his son Jim, who disappeared before they were born. Jim’s quizzing Grandpa about Iram, a mythical city in Saudi Arabia’s Empty Quarter. There Grandpa and partner Jerry discovered a cavern supported by pillars. Smaller caves contained clay jars, metal pots, folds of ancient cloth. Tunnels led off the main chamber, two rough-hewn, two lower-ceilinged but smooth as glass and covered with unknown curvilinear writing. The pair crawled through a low tunnel to a cylindrical chamber. Bas reliefs showed a city of buildings like fangs; another the city destroyed by meteor; still others depicted people (?) migrating across a barren plain, only to be met later with catastrophic flood. The most interesting featured a person (?) surrounded by four smaller persons. Maybe it represented gods or ancestors or a caste system, Jerry speculated. A second cylindrical chamber held sarcophagi full of speckled oblong stones. No, of eggs, most empty shell, one containing a reptilian mummy with paws like human hands. Grandpa filled his backpack with shells, mummies and a single intact egg covered in sticky gel.

Grandpa and Jerry planned on returning with a well-supplied expedition, but back at camp Grandpa came down with rash and fever. Allergic reaction to the egg-gel? Poison? The camp doc was puzzled, but Grandpa lapsed into a coma during which he “dreamt” the whole history of the Iram creatures, more like serpents or crocodiles than humans. The dreams, he believes, were racial and social memory passed on to new-hatched offspring via a virus in the egg-gel. Grandpa learned the serpent-men were masters of controlled evolution, eventually shaping themselves into four castes. Soldiers, farmers and scientists were subject to the mental control of leaders. They spread across the earth, surviving cataclysms by hibernating. After a final battle with humankind, they retreated to Iram to sleep again.

When Grandpa woke he recovered his backpack, and the intact egg. Meanwhile sandstorms had reburied Iram. Grandpa debated to whom to show the egg, never expecting it to—hatch.

The last tape’s damaged. Comprehensible sections suggest that Grandpa’s egg birthed a serpent-man soldier, which Grandpa (conditioned by the gel-virus) could psychically control, though at the cost of flu-like debilitation. He usually kept the creature frozen—dormant. That explains the freezer, Josh insists. Rachel’s more skeptical about Grandpa’s story, especially how the US government recruited him and his soldier for Cold War service. Then there’s Grandpa’s final recorded pondering, on whether his virus-obtained abilities are heritable….

Josh has much evidence to marshal. What about the time they found the freezer open, defrosting, the stench and that bit of skin like a reptile’s shed? What about Grandpa’s travels, maybe on behalf of the government? And Rachel can’t say Grandpa’s naturally mild-mannered. Remember how he avenged a cousin who was wrongly accused of rape, institutionalized, and castrated? He maimed a whole herd of cattle! How about the “hippies” who bedeviled his Kentucky kin? He took care of them, but never said how. With his serpent-soldier? And remember Grandpa’s pride when Josh defended Rachel from bullies: you always redress injury to your own. Even if one of your own is the culprit, because someone who harms his own blood must be the worst offender.

What about vanished Uncle Jim? What if Grandpa let Jim try to control the serpent-soldier, but Jim failed? Or Jim tackled it alone, and failed? Or Grandpa turned the creature on Jim because Jim threatened to reveal the family secret?

Paranoid fantasies, Rachel contends.

Then one Thanksgiving, Josh confronts Grandpa about what’s in the freezer. Ordered to leave, he returns to graduate school. Or does he? Christmas comes, no Josh. Grandpa has a stroke. No response to the news from Josh. In fact, no word from Josh since Thanksgiving. Rachel and Mom find his apartment abandoned, no note. The cops, who’ve found pot, think Josh ran afoul of drug dealers.

NOW: Rachel goes home and picks the basement freezer locks. Digging into ice, she touches not Josh’s corpse but pebbled skin, a clawed hand. Sudden fever overcomes her. She falls to the floor, yet she’s in the freezer too, struggling free, seeing colors for the first time, seeing herself beside the freezer.

She understands.

In her (borrowed? co-opted? shared?) body, she staggers upstairs. The health aide’s left Grandpa alone. Memories of earlier kills besiege her, including the slaughter of a young man who must be Uncle Jim, with Grandpa wailing. Then a young man who must be Josh, Grandpa screaming “Is this what you wanted?”

Grandpa sits helpless in his bedroom. He’s unsurprised to see Rachel/Soldier, confesses to Jim and Josh’s deaths. Did he experiment with both or just kill Josh? It doesn’t matter. Rage sinks Rachel deeper into the creature she inhabits. She brandishes claws, fangs. She hisses.

Something like satisfaction crosses Grandpa’s face. “That’s…my girl,” he says.

What’s Cyclopean: Langan nobly resists the temptation of truly Lovecraftian language, though his city is as deserving of the “cyclopean” descriptor as Howard’s version. Spare but precise descriptors are more his style, and we get to know Grandpa’s cinnamon-and-vanilla scent very well.

The Degenerate Dutch: The lizard person caste system doesn’t seem like something you’d want to emulate. Fans of Babylon 5 may never look at the Minbari the same way again.

Mythos Making: The lizard people of the nameless city aren’t at the top of most people’s Lovecraftian monster list, but their aeons-old, not-quite-dead civilization and (in the original) surprisingly simple-to-interpret bas reliefs presage the Elder Things. The similarities are particularly noticeable here.

Libronomicon: The Hawthorne quote at the end of the story is… on point. The original work itself appears to be primarily nature observations and story notes, though there is an edition put out by Eldritch Press.

Madness Takes Its Toll: However easy it is to mistake an infusion of lizard person knowledge for delirium initially, it seems likely to have serious long-term mental consequences later.

Anne’s Commentary

Synchronistic event: After finishing this story, I checked the author’s website and found he’d be reading this weekend at the H.P. Lovecraft Film Festival in Providence. I’m hoping to go and pick up his novels, because I am impressed, most impressed. I was also tickled to read a story partially set in my old stomping grounds of Albany, New York. Like Josh, I went to the State University of New York (SUNY) at Albany! I had a friend who was a philosophy major (like Josh) there! I had other friends at Albany Law (like Rachel)! I don’t know, I sense strange stars aligning out there….

The nonlinear, “multi-media” structure serves “Children’s” novella length well, getting a lot done in relatively few pages. The present time opening introduces central character Rachel via her unusually sharp senses of smell, hearing and touch, then subtly reveals the blindness that makes them essential. Grandpa’s huge old freezer, “squatting” in a corner, is not reassuring. Nor is Rachel’s thought that with what she’s come to do, it’s better she’s blind than sighted.

The “multi-media” aspect is introduced in the next section. We get the dope on Grandpa’s discovery of lost Iram through a series of audio tapes. Given how so much in Grandpa’s house is kept locked—that freezer, his second floor domain—it’s highly significant that the trunk holding the tapes is unlocked. Josh is right to take this as an invitation to snoop, er, obliquely learn some family history. The freezer is the focal point of Rachel and Josh’s curiosity and appears in several sections. Three more center on Grandpa’s history, with an emphasis on his capacity for vindictiveness in the service of family and clan.

The reader may wonder why Langan spends so much of his limited time recounting the “hippie wars” and the sad tale of Cousin Julius and the Charolais cattle. In retrospect, it’s clear that Grandpa wasn’t just rambling aimlessly, like one of those old fellows on the general store porch with whom we’ve grown familiar. Nothing Grandpa does is aimless or uncalculated. By telling Rachel and Josh these stories, he’s gauging their capacities to take over his job one day. To control the Serpent-Soldier, one must be strong-willed and (in a particular, rather narrow sense) righteous. One must not be squeamish or averse to violence in the cause of justice. Josh looks like a good prospect, for a while. He smacks mean girls upside the head with his bookbag to avenge a cruelly teased Rachel. He’s excited by Grandpa’s present of a buck knife. Now, a buck knife was Grandpa’s weapon of choice in maiming his villainous uncle’s cattle. He does not give it to Josh as an afterthought.

But Josh misuses the knife, not keeping it secret but showing it off at school. When his father takes it away for a time, he forgets to reclaim it. Whereas the only time Rachel gets to handle the knife, she does so with a certain wonder and relish. It’s the same sort of gusto she displayed in root beer-toasting Josh for his attacks on her tormenters. “Knife wants to cut,” she says, echoing Grandpa, even imitating his voice.

Other nice details: Josh goes on to study philosophy, Rachel law. To Grandpa’s mind, which type of student should sooner be trusted with the “keys” to a velociraptor assassin? Josh has no physical handicaps, but Rachel’s blindness may in fact make her more fit as Serpent-Soldier operator. Its vision, presumably not exactly like a human’s, is her only vision. She doesn’t need to adapt to it. She may well find it a reward, an inducement to inhabit the soldier.

And in the end, Rachel succeeds where Uncle Jim and Josh failed. She’s Grandpa’s girl, all right—at the end of his useful life, as he must see it, Grandpa doesn’t mind being her first victim. She both frees him and follows the family code: You always redress an injury to your own.

She is the knife.

About the serpent-people. I’m intrigued by the description of their egg-sarcophagi, in which most of the eggs have already hatched. What’s more, there are only three mummy corpses, three still-births. I assume that whatever crawled out of the empty shells kept crawling. En masse, deeper and deeper into the caves beneath the desert, virus-instructed by their primordial ancestors in the ways of survival, expansion, dominion.

Grandpa, I fear, is gone. But maybe Rachel will switch from law school to archaeology and make a trip to the Empty Quarter one day….

Ruthanna’s Commentary

This, you guys, is what I keep reading these stories for. “Children of the Fang” gets off to a slowish start, but works its way up to deep time and ancient undying civilizations and hints of my favorite Lovecraftian civilization-building data dumps. Humans are forced to take on alien knowledge and perspective and come away changed. But how changed, we can’t tell—how much of Grandpa’s later nastiness comes from the racial memory intended for a lizard warrior, and how much did he always carry? Maybe he gained his symbiosis with the creature because he was already predisposed toward its psychology.

The body-switch at the end is particularly well done. When Lovecraft writes these things, he shows wonder and fear in equal measure, while telling us only of terror. Langan acknowledges both sides of the experience. In an especially nice touch, Rachel’s blindness means that some of what’s shocking new to her is familiar to most readers—which both makes us a little alien from the story’s point of view, and gives us an extra handle to follow the wild perspective in which she’s suddenly immersed.

Langan’s lizard people are, in fact, more alien than Lovecraft’s. No inexplicably easy-to-follow bas reliefs here. Though a couple of carvings are comprehensible, most are at the “maybe it’s a fertility symbol” level that real archaeologists struggle with even when dealing with pedestrian human symbols. The degree to which the memory infusion works—and doesn’t—in Grandpa seems believable to me (assuming memory infusion possible at all). After you hit a certain point in evolution, a neuron is a neuron and a hippocampus is a hippocampus. But bird brains, and presumably therefore saurian, don’t follow quite the same organization as primates. Would a thumb drive for one work in the other? Probably. Would it cause a nasty system crash in process? You bet. And that new OS is going to run a bit buggy, too. But the human brain is remarkably flexible—run it will.

The family dynamics are disturbing and fascinating. They’re also the least Lovecraftian thing about the story—“Children” completely lacks the distance Howard gained through his nameless narrators. The complex characterization adds power to the typical Lovecraftian trope of the 3rd-hand narrative, especially given the mystery around what happens to the listener—and therefore by implication to anyone else who learns the same thing. The lacunae in family stories tell you a lot in most families. It’s just that this gap holds much weirder material than it would in a more literary piece.

“Children of the Fang” also stands out for its treatment of disability. Rachel’s blindness is treated matter-of-factly even while it shapes the story, from the emphasis on vivid non-visual detail throughout up through that final transformation. (And note that rather than the more common literary complete absence of vision, she has the minimal ability to see that’s more common in real life. Langan’s paying attention.) The mentally disabled Julius in Grandpa’s flashback gets his moments as well, however nasty his story. For both of them, we see how their experiences are shaped both by their actual physical condition, and by how their families and society accommodate them—or don’t. One wonders if Rachel’s better experiences and opportunities are shaped, in part, by Grandpa’s memory of what he didn’t do for Julius. Or by some later intimation that “family comes first” while still alive, too.

And after, of course. Grandpa believes firmly that you should get revenge on anyone who hurts your family… and we know what he’s done. “That’s my girl,” indeed. He’s been waiting for this.

Next week, we return to a disturbing play and a peculiar color in Robert Chambers’s “The Yellow Sign.”

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.