A meditation about the evolution and influence of a song written in 1902 over the next 150 plus years.

FREDDIE WEYL IN TORONTO, 1902

Freddie’s head rested on the music rack as he murmured into the piano’s keys possible and probable rhymes, slant or assonant, for moon. He accompanied each syllable with a dull minor chord from his left hand. June. Raccoon. Spoon. Croon. Womb. Harpoon. High noon. Tomb. Gloom. Wound.

The last word stuck and a terrible, irresistible lyric formed. He droned it through his nose: The June moon it is a wound. High noon gloom of my little room, and so the tomb.

How much they loved these loony, crooning vowels. Words that turned all singers into doves, with billing and cooing that sounded to his ear—he, who had lived so much of his life under the eaves of pigeon-infested houses—like an asthmatic climax. Hoon. Hoon. Hooooon.

It was hard to write about the green fields of somewhere-or-other when he heard only infernal pigeons, the clutter of wheels on pavement, the shout of boys, the rage of drivers. Despite the noise, Freddie still conjured moon-drenched country walks in terrible songs published as “F. Wilde” because he could not put his own name to them. Songs all written for a girl in Winnipeg with a quarter to spare and a pianola in the parlour. He’d seen modest cheques so far, which was why he was keen to keep the harvest moon in his heart, and so avoid his natural tendency toward moon-tombs and Cdim7.

If one was to write a song about the moon, he thought, one should think of its true nature: its distance from earth, out there among the meteors and comets; one should consider the luminiferous aether through which it sailed. The number of moons expanded yearly, he had noticed, as telescopes grew more powerful, and the people of Earth more sharp-eyed and watchful. There were multitudinous moons, not just their own, but Phobos and Deimos, accompanying Mars and its canal-scored deserts, Io and Tethys and oceanic Titan.

What they all needed was a song about an observatory, signaling Luna or any of her sister-satellites, how, one day, a light might wink back at them from the dark.

He thought of the canals of Mars and its moons, or the still-unnamed bodies that circled the sun in orbits invisible to the naked eye. He liked that feeling, of distance, an expanse so huge his mind ground to stillness when he tried to imagine it. His fingers found the keyboard, and it seemed that an enormous, empty space formed between the question and the silence of its non-answer—

Where does that water run? he asked, and thought of Schiaparelli’s canals, and the spidery Venusian webs Lowell had seen through his telescope. Where does it run?

Maybe out. Maybe into the black on the other side of the sky.

VOCAMATIC HAND-PLAYED RECORDING, 1904

Six Songs As Sweet As A Garden Stream, including “Where Does That Water Run?” and “Waiting For You, My Dear” by that beloved American tunesmith, F. Wilde.

For best results, choose a Dekalb pianola!

LILY GIBBS, 1898–1980

Vocals and Autoharp. Best known for her signature song, “Where Does that Water Run?,” an Appalachian ballad of uncertain origin, recorded ca. 1929. Advertised by OKeh Records as The weirdest melody that ever stole out of Tennessee.

LILY GIBBS PLAYS THE EXIT CLUB, 1975

The parking lot behind the Exit only fit three cars and it was full, so Pat squeezed her Volkswagen behind the dumpster and knocked on the door to Ken’s office. By the time Ken let her in she’d smoked her second cigarette down to the filter.

His eyes were tiny and red-rimmed. Pissholes, her father would have said, in the snow.

“Thanks, Patty,” Ken said. “You have no idea how grateful I am.” He leaned in close. “The vibes, man, the vibes. The woman is a menace.”

“I’m lending my car to a menace? What is she going to—”

“A reactionary kind of a menace, not the kind who’s gonna wreck your car. She needs to go to church, or buy a new hat or something. She hates me already—hates drunkards, that’s what she called me—and weed, and cocaine too, I assume. Though it hasn’t come up.” He barked, or maybe laughed. “If she wasn’t Lily goddamn Gibbs I’d’ve locked the door.”

That was when she heard Lily on stage. “Where Does That Water Run?” Lily goddamn Gibbs might be past seventy, her voice reedy, but she still possessed that quality Pat had first encountered when she was a kid with a crystal radio set, listening to the air in the middle of the night. Some January evening she had put the little beige earpiece in and slid the spring along the wire until she heard a melody in the static: Where does that water run? Lily had first asked her when she was eleven. She had not yet answered, though the inscrutable question remained in her mind.

On the wall beside the entrance someone had tacked up the poster: an ink-lined Lily Gibbs cradling her Autoharp, a face all tight-stretched skin over sharp bones and hollow shadows, her eyes huge and dark. The Exit Club. $2.50 weekdays. $3 weekends.

Pat wanted so very badly to say something, maybe about the crystal radio set and the beauty of a song emerging from the sheets of static. “It’s really pretty,” was all she could think to say while looking at the poster, her voice a shade too bright.

Lily Gibbs—really, truly Lily Gibbs, of the remarkable voice, of the peculiar Autoharp tunings and the irresistible question—just looked at her.

Ken carried on in the silence. “Yeah, it’s pretty good, I like it a lot. I like his work. She’ll just need the car for the afternoon, is all. I can’t thank you enough, Patty, I really can’t. You’re on the list. Forever. I’ll put you on the list forever,” followed by the humourless bark.

In the alley, Pat unlocked the Volkswagen and handed Lily Gibbs the keys and took in her incongruity, so much more obvious in daylight. She wore a lavender double-knit suit with slightly dingy white buttons and piping. Her hair had been teased into a tower of setting lotion and Final Net. As though she didn’t notice she was being watched, Lily took a rat-tail comb out of her purse and scratched her scalp. Pat thought of the hostess at the first place she’d ever worked banquets, whose elaborate hairstyles were set once weekly, and who was otherwise trapped beneath them, and scratched the same way with her rat-tail comb when she still had a day to go before her shampoo.

For her part, Lily glanced from Pat’s head to her feet and back again to her eyes. It felt a lot like going down to the Legion to collect her father on a Saturday afternoon, with the Legion wives looking over her jeans and her long, undressed hair and her sandals with that same glance, from inside the same lavender double-knit suit and fearsome bouffant. The same oppressive censure, but this time from Lily goddamn Gibbs herself.

Later that night, Pat got the Volkswagen back with an empty gas tank and a strong scent of lily of the valley. She slipped in past the dumpster, along the corridor past the storeroom, and emerged behind the bar, where Ken was standing, his hands pressed flat on the scarred wooden top, his TEAC reel-to-reel beside him.

Lily Gibbs was just taking the stage in her kitten-heeled pumps, accompanied by men in neat ties and dark suits a little shiny at the seams. Pat’s mind went again to the Legion, collecting her father from the smell of stale beer in old carpeting and a still basement room shut up tight against the summer heat.

Then none of that mattered, not her immediate mistrust of middle-aged men in dark suits, nor the disapproval from the woman on stage. None of that mattered because Lily Gibbs opened her mouth and sang for a ninety-minute set that ended the only way it could end, with the terminal question: Where does that water run, poor boy? Where does that water run?

The song began with a fairly conventional bluegrass arrangement, a lot like the 1950 recording, Pat thought, but then the instruments dropped, and their voices rose in a capella discord, the guitarist’s baritone, the bassist’s tenor. A full octave higher, Lily Gibbs carried a lonesome countermelody.

Then the bottom of the stack dropped out as well, and it was only Lily repeating the question: Where does that water run? Where does that water run?

The last long vowel lengthened into a drone, so pretty soon there weren’t any words, just a restless sort of pain. It was like the sound had found some sympathetic resonance inside Pat at a confluence of bone, and so her eardrums shuddered like she was resting her head against an overdriven speaker. The sound conjured darkness, a limitless space on whose edge she perched, and there was nothing but Lily’s half-gone voice, and a feeling inside like a rupture. There might have been a trickle of blood in her ear. Burst vessels in the whites of her eyes. The vertigo of a sudden change in blood pressure as she found herself standing.

She felt like she was looking up into the black. Or maybe it was down into an equally black abyss. It didn’t matter which, because the black surrounded her. She might sense other things—a shitty underground club in Vancouver, the streets around suffused with cut grass, or blooming trees, the cold snap of winter ozone—but it was the black that mattered, empty black with all the tiny windows of the world lit like stars. Above them sailed moon after moon, through the entombing black, a darkness so vast it stilled her beating heart, slowed her mind to a tick like a clock, then slower even than that.

PAT MAKES A MIXTAPE FOR HER DAUGHTER, 1991

There’s the sound of audiotape first, that familiar low hiss. There’s a crackle, then what might be a mandolin. Someone, somewhere, a long time ago, resets the turntable from 45 to 33 ⅓, and there’s the skirl of sound decelerating. Then Lily Gibbs:

Where does tha— tha— tha—

Sometime, long ago, Pat nudged the turntable’s needle.

—that water run?

IN THE BLACK, 31 YEARS AFTER EGRESS, 2068

What do I miss? Gravity, mostly. I miss gravity and oranges and baths. I miss outside, as an operative concept. We’re never outside in any meaningful way.

I miss information, which in retrospect is the biggest surprise. If you’d asked me when I was a kid I’d’ve thought, you know, interstellar travel, generation ships, they must know everything. I miss the old kind of Faustian, compulsive collection of stuff that used to happen because there was always room for more. I’m old enough to remember Google and how many terabytes of data I kept just because I could.

But it’s amazing how vulnerable information is when your resources are limited and the infrastructure is disintegrating around you. It seemed absolute at the time. Like, Wikipedia, you know? How could something so big be so fragile? It would have survived better if it had been written on those clay tablets you read about from Mycenae, the kind that tell you how many bushels of barley they grew. The kind of tablets that got accidentally baked in some apocalyptic fire, and survive because they’re stone.

It’s not that we’ve lost everything. It’s just—there are gaps.

Like, for example, there was this song my mother used to sing. It was just a folk song. I never thought to look for it until it was too late. I don’t even know where she heard it. Maybe some old mixtape from Grandma, the kind you used to sing along with in the car.

Anyway. I still remember part of it: Where does that water run, poor boy, where does that water run? I sang it to my own grandkid and she said that water runs into the purification system. It took her a while to understand that running water meant something different on a planet, where water runs away into the dark somewhere.

Lily Gibbs. That was the singer’s name. Lily Gibbs. I can almost hear her voice. Almost. I can hear Mom singing, too.

When it makes me lonesome, I like to remind myself that it’s still out there, running into the dark. The song would have been broadcast, right? Mom or Grandma heard it on the radio, so the signal isn’t lost, it’s just out of reach, traveling outward in this kind of envelope, a slight disruption of the aether.

So even though my mom is dead, and the audiotape my grandmother played in her car is at the bottom of some flooded city street—even though it’s all gone Lily Gibbs is still careening through space along with every other sound we’ve ever tossed out there. And the basic message, whether it’s Lily or Marconi, is always the same: We are here.

Somewhere out there someone—a sort of person we can’t imagine—could raise their hand or whatever into space and use the same sort of tech to catch the thin, ancient hiss of a human voice, stretched to nothing by distance, but persistent in the darkness. We’re so far gone now, out past the planets, in the emptiness between home and the nearest stars, and it’s comforting to think of that woman, outracing us all into the black. Where, she’s still asking, does that water run? Lily, high and lonesome, spilled out past the dark rim of the solar system, and into the emptiness beyond.

KEN’S NEPHEW REMEMBERS HIS UNCLE, 2026

We found them in the basement exactly where Kenny left them in like 2013, in his place in Richmond. It’s all sand there. You know how bad the floods hit Steveston. We were lucky we recovered any of it, really.

It took me a while to get parts for his old TEAC TASCAM. 60 series. Those were awesome machines. Uncle Kenny took that shit pretty seriously, even if he was kind of a cokehead. He must have got it in ’74 or something. Anyway. I had to source parts from all over, and we finally got it working and you should’ve seen the collection: John Prine, Tim Buckley, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

I was just listening to them, thinking, Oh, this is cool. But then I get to Lily Gibbs. There was some nice work from Jimmy Staples on mandolin, but it all didn’t hit me until the end.

I mean, I knew “Where Does That Water Run?” from when I was a kid messing around with an acoustic guitar. It’s an old song.

You’ve heard it? No? Yeah, a lot of her work was destroyed for the shellac during the Second World War, and the masters were all recycled. But that was pretty standard back in the day. Anyway—this live performance. At first it’s just ordinary stuff, you think. The microphone is a bit wonky, and maybe there was some chunkiness in his gear that night, a rough edge, even though he wasn’t that bad of a tech.

But when she drops the Autoharp, and loses her stack, so it’s just her voice, the drone, then a keen, then a drone, you can’t help but feel something, something physical. I don’t think there’s a word for that sound.

I met a guy doing sound art once in, like, Sweden. The performance he did seemed really familiar, like the tonal qualities he was trying to produce, something rough but kind of like hypnotic, and jarring. I spent the whole night trying to place it, and then afterward I go up to him and say, “Where does that water run?” And his face changed in that way you sort of recognize. Because that’s the question, isn’t it? The closest you can get using words. The closest you can get to Lily Gibbs dropping her Autoharp and singing, because what good are words at that point?

I made .flacs if you want them.

TORRENT DEMONZ, 2018

Lily.Gibbs.11-14-1975.Exit.Club.torrent

Readme.txt

LilyGibbsExitClubPoster1975.jpg

- IWishIWasAMoleintheGround.4.17.flac

[…]

11.WhereDoesThatWaterRun.13.55.flac

Seeders: 0

Leechers: 37

3 comments

Seed pleeeeaaaase!

Seeders? My mom put this on a mixtape for me!! I haven’t heard it in twenty years!

Does this actually even exist?

A CRYSTAL RADIO SET, 1966

It was Chris who got the sixty-five-in-one electronics kit for Christmas, but he didn’t finish making anything, so after New Year’s Pat quietly adopted it. She opened it up on the kitchen table, kneeling on a chair and reading the instructions and tracing her finger over the diagrams, trying to understand capacitor and space age integrated circuit and wondering if she could really truly make a lie detector. She put the radio together that night thinking about how, if you were lucky, you might hear a signal from the moon, maybe. If there was a signal, you might. If you were lucky and could tell the difference between static and aliens.

The first time she put the little beige plug in her ear she held the radio in one hand and put her other hand on her lamp, and it was magical to hear the signal change, until—in among the hushing and hissing sheets of static—she began to hear something like a voice. It got even better when the sun went down. That was okay for a while, but then the lamp wasn’t enough and she thought about the maple tree outside her window, too far for an exit, but she could climb it with a spool of copper wire borrowed from her father’s workbench, and string it in her window.

Many nights she listened to sounds from so far away they had bounced over the ocean and against the upper atmosphere, then ricocheted down from the nighttime sky, and found their way to her ear. Sometimes just a voice saying, Goodnight folks or Looks like another hot one. Sometimes Spanish and Portuguese—so she guessed—and the sounds of Pacific Islanders, the nasal accents of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Stations down the coast in Washington and Oregon that ran The Shadow all night. Once she heard the theme from The Third Man, but static swamped the zither before the radio play began. Sometimes a thin, high tenor. Long interviews and commentaries in Russian and Cantonese and who knew what else.

Then, through the veiling static, a woman’s voice.

At first all she could hear was the melody, but then she could make out the refrain: Where does that water run, poor boy? Where does that water run?

She knew she was listening not to the music alone, but also to the luminiferous aether—the phrase she had seen in the World Book Encyclopaedia entry about space. It was the substance in which planets and radio waves all sailed, the deep and the black.

FREDDIE WEYL IN TORONTO, 1954

Freddie sometimes heard songs he’d written, or songs he might have written. Maybe from the speakers outside a record store. Maybe on the radio set on the windowsill of an apartment overhead as he took his evening walk. They’re often in new and peculiar arrangements: “Waiting For You, My Dear” became the signature song for a local dance band and when they broadcast Saturday Night from the Starlight Room, he sometimes heard it by accident, their closing waltz.

“Where Does That Water Run?” was not so common, but he thought he had heard it on the radio once or twice. Unlike “Waiting for You, My Dear,” which grew more elaborate with each iteration, until it needed a thirty-piece orchestra, “Where Does That Water Run?” seemed to have become a folk song. He heard for the last time while he was sitting in a coffee shop unable to sleep, smoking and eating butter tarts. The kid who worked late Tuesday nights that spring had a taste for folk music, and tuned to a station out of Buffalo, all ballad stanzas and old race music and banjos.

He didn’t recognize it until the first chorus because it seemed to have collected new lyrics, but the song still asked: “Where does that water run?” from the cheap Bakelite setup beside the cash register. It was an unfamiliar arrangement, though as he reached through the composition in his mind and felt the rightness of its discordant harmonies, the thud of a guitar, the manic fiddler with the cheap bow, the woman’s nasal and remarkable voice, Freddie approved.

Paying his bill, he considered telling the kid who worked late Tuesday nights that the song he was singing along with? It was one of his own. Though it wasn’t, really, because it was one of F. Wilde’ compositions. And who was F. Wilde?

“That song, you know,” he began, then he didn’t know what else to say.

“I know, it’s something,” the kid with the beard explained. “I have it at home—it’s a re-release from OKeh Records.”

“Yeah?”

“The thing about folk songs is they always sound,” the kid said, confidentially, as though he’d often rehearsed the thought, “like they’ve always been here, and they’ll always be here. You know?”

And it felt true, even if it wasn’t, so Freddie just said, “Yeah, that’s right,” and left.

LILY GIBBS, AGE SIX, 1904

When she was very old it seemed to Lily Gibbs that she had spent her childhood in a house without lamps, set in the winter dark between narrow hills, where the rain pattered constantly at the little windows in the parlour.

She remembered the parlour most clearly because it was where her adoptive great-aunt kept the pianola—the huge one, flying on the elaborately carved wings of many wooden angels—that sat untouched until she found it. On the walls around it there were pictures made of wool, Lily remembered. Bible verses. Lambs and heartsease and doves.

In the enormous and melancholy dark of the parlour loomed the pianola and she felt her way toward it, following its gleam and hulk in the rainy twilight of November. There were three pieces of music in the parlour, dusted weekly, but which remained otherwise untouched on the music rack: a collection of hymns; a march; and “Where Does That Water Run?” on a huge, ivory sheet dated 1902, illustrated with hollyhocks and willow trees, a stream at inky sunset.

Lily was not allowed into the parlour except on rare and special days, or when—as was the case today—she was alone and slipped in to set her fingers on the untuned keys. Somewhere inside the wheeze and thunk might be music, and on that day she kept playing until Aunty found her and chased her back to the kitchen.

As she played she sensed outside the window a world so huge it slowed her thinking, where lightlessness was a substance in which she seemed to drift, as she drifted in the parlour on the sounds the pianola made. Somewhere the rain was falling, and the drops raced down the panes of glass. Somewhere the water was running, though she did not know where it went. West, she thought, or just—in the manner of a child—to a hazy place called far away, that was emptiness itself. Out in the dark, she thought, where does that water run?

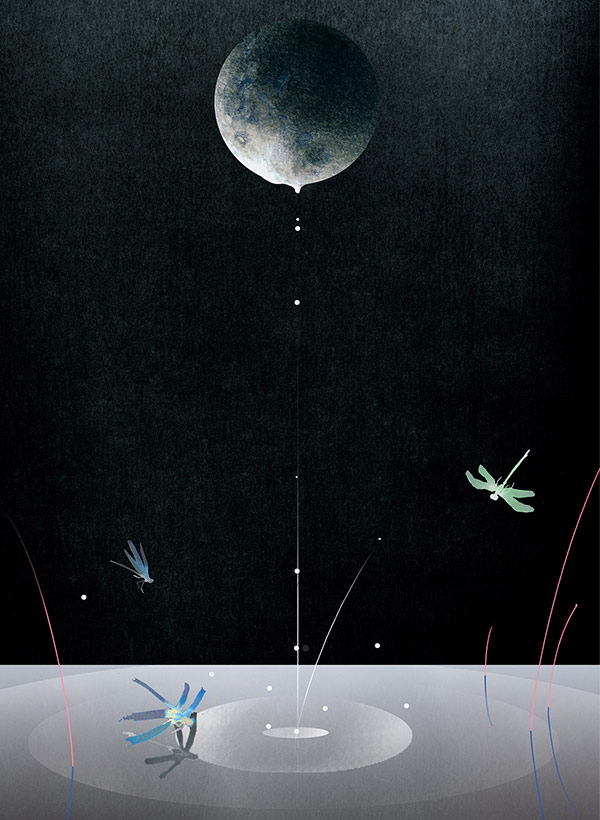

Beyond her ken, in the empty stretches of the sky, rolled all the moons she could not see, filling the deep with light.

“The High Lonesome Frontier” © 2016 by Rebecca Campbell

Illustration © 2016 by Linda Yan

This was so beautiful it brought tears to my eyes.

This was lovely and I shall be pleased to purchase a copy to support the author. :)

Captures a sense of timelessness, no beginning or end just an unending timelessness.

This is a remarkable story which captures so much about music and yet is about so much more. I think it’s the best short story of the year I’ve read.

Wow, I am at a loss for words. Campbell’s story is everything you all have said, and much more. Easily one of the best short stories I’ve ever read!

Brilliant story!

Music, mystery, majesty. Lovely and haunting.