Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

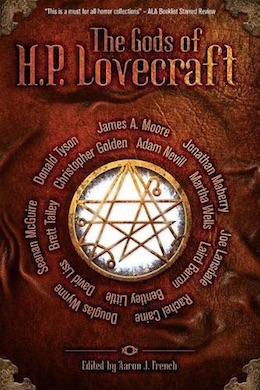

Today we’re looking at Rachel Caine’s “A Dying of the Light,” first published in Aaron J. French’s 2015 collection, The Gods of H.P. Lovecraft. Spoilers ahead.

“I turned back to the bed, and the frail little woman dying on it, and another inexplicable feeling swept over me. A hot flash of utter horror, as if I was starting at something that should not be, then I blinked and it was over, except for the incredibly fast pulse of my heart and the sickening taste at the back of my throat. Acanthus Porter sat up in bed and looked at me with cold, shining blue eyes.”

Summary

Rose Hartman is an aide at Shady Grove, an Arkham nursing home. Never “squeamish about bodily fluids,” she doesn’t mind the job. Sure, it’s hard to watch Alzheimer’s patients “struggling to climb out of whatever pit they’d fallen into inside their skulls,” but she enjoys making “their dark days a little brighter.” She’s gotten a reputation as an “Alzheimer’s whisperer,” and her nursing supervisor calls her “Saint Rose” as he assigns her to a new patient who requested her by name.

Or whose people requested her, for Acanthus Porter is an end stage sufferer, unresponsive and wasted. It’s tough to reimagine the movie star she once was. Rose is settling the old woman in when a hot, clammy wind envelops them out of nowhere. It smothers Rose. She covers her face, fighting the urge to vomit. And Acanthus reacts still more strongly. She sits, stares with cold blue eyes at Rose, then emits an inhuman metallic shriek. Rose’s answering scream is all the nursing supervisor hears. She doesn’t tell him what happened—she can’t afford to get fired for sounding crazy.

Acanthus’s condition unaccountably improves. She stands and walks, albeit like a creature who’s never done it before. She struggles to talk, studies Rose’s every movement as if trying to learn how to be human again—or for the first time. Rose can’t shake the sense Acanthus isn’t really Acanthus anymore. She is… some stranger.

The former star becomes a media sensation. Doctors study her case without uncovering answers. Rose gets some of the spotlight, which she dislikes. Over a year, Acanthus learns to walk, talk, read and write, rehabbing into “something that was almost normal, but never quite… human.” Her adult children finally visit. Both are shocked and insist this woman isn’t their mother. The son walks out; the daughter lingers until Acanthus speaks in her strange, oddly accented lilt. Then she too flees in horror. Acanthus is unconcerned. She’s busy writing in a weird script and illustrating the manuscript with weirder plants. It’s a history, Acanthus explains, but she won’t say in what language and scowls when Rose snaps a picture.

Rose does a reverse image search on Google and learns the script matches cryptic writing in the Voynich manuscript, a 15th century document kept at Yale. How could Acanthus reproduce it so perfectly? Further research unearths a Miskatonic University lead. Professor Wingate Peaslee II posits the Voynich manuscript is connected to his grandfather’s famous amnesia. After a nightmare about alien towers and inhuman shadows, Rose consults him.

When Rose asks to see Nathaniel’s papers, Wingate hesitates. She has a subtle look that he associates with people who met Nathaniel during his “alienated” phase. He asks if Rose has started to dream yet, and describes his own near-identical dreams. Is she sure she wants to plunge into Nathaniel’s story?

Rose persists. She reads Nathaniel’s account of an alien race (the Yith) who mind-traveled through time and space, studying other sapients and periodically avoiding extinction by possessing their bodies. Nathaniel had elaborate dreams about inhuman cities and cone-shaped creatures among whom he lived, body-switched. The account of his Australian trip is even more unbelievable. Wingate shares pages Nathaniel drew late in life, similar to Acanthus’s. Nathaniel’s obsession, sadly, ended with his death in the Arkham Sanitarium.

Rose doesn’t tell Wingate about Acanthus. Soon after, Acanthus consults with a lawyer. Her children appear, demanding to know why she’s cancelled their power of attorney. Acanthus calmly says she’s taking her affairs back into her own hands. She will need the freedom and money to travel. She doesn’t need her family any more, but she does need Rose. Rose’s protests are met with the offer of a million dollars. By phone, Acanthus’s lawyer confirms she has more than enough money to pay, but says he wouldn’t accept for any amount.

The lawyer probably has more than a couple hundred in the bank; for Rose the million’s too great a temptation. During a long disorienting trip to Australia, she weakens, as if drained by her employer’s proximity. At last they reach Melbourne; from there, they journey into the great desert, stopping at last among wind-eroded stone blocks. At night four other people emerge from the swirling sands: a South American man, an African man, a Chinese woman and her visibly anxious young male companion. They speak of people who “sacrificed” too soon, and Rose has visions of three men who took poison and died, ritualistically. At least one made it to Australia and still “echoes” here among the tumbled ruins. Rose feels the energy of those echoes, of a former city. The young Chinese man runs in panic, stumbles over a dark stone, screams as if consumed. He dies with oily blackness covering his eyes.

Acanthus and the other three turn to Rose. Somehow they send her under the sand, into the buried ruins. A sucking wind and tendrils like those Acanthus drew on her plants suck her down. Something whispers, Rose, the time is here.

She runs toward blue light, finds a massive library of metal-encased tomes. One case lies on the floor, and she reads the Voynich script inside. Acanthus whispers that she, Rose, has been chosen to finish the work of the Yith on Earth, to imprison the darkness at the heart of the planet and save her race. She must close the doors Nathaniel Peaslee unknowingly opened during his visit decades before.

Pursued by rogue wind, Rose discovers a yawning trapdoor. She can’t budge its massive lid. Conical Yith, or their ghostly memories, appear, and she tells them to send her to a time when the trapdoor was closed.

Rose falls back a hundred years. The door’s now closed but bulging from the evil that scrapes on the opposite side. But the Cyclopean archway above is crumbling. Rose climbs, pushes out the keystone, brings millions of blocks down on the door. She’ll be buried along with it, but as Acanthus whispers in her ear, everything dies, even time, even the Yith, the four above who can flee no more.

Rose falls, the light dies, she laughs.

She wakes in a chitinous body with jointed legs and a hundred eyes. Similar beings are trying to comfort her. She’s in a nursing home for monsters, to which Acanthus has sent her as a final gift of life. Rose is now last of the Great Race. One day she’ll write a manuscript about the vanished humanity her sacrifice couldn’t save forever. In an opening of the burrow where she struggles, she sees a red and feeble sun. She’s there, at the dying of the light. And she laughs.

What’s Cyclopean: The lost library of Pnakotus, though not described in such precise terminology here, is definitely cyclopean.

The Degenerate Dutch: The Great Race does not deign to notice petty distinctions among humans.

Mythos Making: The Yith are one of Lovecraft’s last and greatest creations. Not only do they feature centrally in “Dying of the Light,” but our narrator actually gets to sit down with Professor Peaslee’s grandson (Prof Peaslee the 3rd?) and… read “The Shadow Out of Time.”

Libronomicon: The Voynich Manuscript is legit pretty weird. “It’s probably Enochian or something” is one of the more sensible possible explanations.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Alzheimer’s sucks. Exchanging minds with a cold and calculating alien intelligence from beyond the stars is honestly much nicer.

Anne’s Commentary

In her author’s afterword, Rachel Caine confides she has an intimate acquaintance with that modern scourge of long life, Alzheimer’s disease: Her mother is among those afflicted. Reading “Shadow Out of Time,” Caine recognized similarities between Nathaniel Peaslee’s alienation and Alzheimer’s, which she develops here with compelling emotional intensity. I was blown away by the opening, the unfolding of the Acanthus riddle, and that far-future close. Rose is a believable and sympathetic character, while Acanthus simultaneously fascinates and chills as an alien in stolen human form.

The trip to Australia, though.

“A Dying of the Light” runs about 10,000 words. To accomplish all it sets out to do, I think it could use an extra 40,000-90,000 words, that is, novel length. The Voynich manuscript, the Lead Masks and Taman Shub, all real mysteries, are incorporated into the central plotline too sketchily for the “oh wow” effect elaboration might have supplied. The suicide cases are especially confusing, curious strands that never quite braid with the narrative.

The Australian climax also feels cramped by insufficient story space. The set-up at Shady Grove takes 15 pages, the desert sequence about 6 and a half. This section reads to me more like afterthought than destination, an effort to give the dedicated fans more Lovecraftian action. The dedicated fans are likely the only ones who’ll understand what’s going on with Acanthus. They’re definitely the only ones who’ll recognize the threat under the trapdoors, and the calamity a resurgence of flying polyps would precipitate.

Mythos readers, on the other hand, may quibble with such details as the noncanon Yithian power of projecting Rose into the past in her own body. They may puzzle over the suggestion that Nathaniel Peaslee opened doors for the polyps—didn’t he find the traps already open? Then there’s the unanswered mystery of Rose. Why is she the Chosen One? [RE: Two words—bad wolf.] And if Acanthus and friends still have the power to send her into the past, then into the future, into a Coleopteran body, why can’t they close the traps themselves? Rose, satisfyingly credible as an Elder Care Technician, becomes a less credible rock climber and keystone shifter when so suddenly endowed with this athleticism and engineering acumen. And how is she the last of the Great Race? Was she a Yith sleeper agent? Could be, but where’s the set-up for that? And why do the Yith care if humanity perishes? Because human extinction is premature, now Peaslee’s screwed up the universal timeline? Could be. Again, the set-up?

Oh, I wish this story had stayed at Shady Grove. I would have loved to see Rose and Acanthus’s relationship developed further, to have watched Rose struggle through the moral conundrum that would have been hers once she realized what lived in Acanthus’s body, wresting away the last of the host’s mind for its own cold purposes. Would she try to stop the Yith usurper? Find a reason to go on caring for it?

Yeah, that would be a much different tale, and how unfair is it for me to do this kind of Monday Morning Mythos-Expansion? Offense admitted. And I would hate to see that sweet epilogue cut. It creates such a perfect symmetry, with Rose the caregiver now Rose the cared for, Rose the grounded now Rose the (at least temporarily) alienated and incomprehensible, in a body running on autopilot toward world’s end and the dying of the light, against which we may all rage along with Caine.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

The Yith are, as I may have mentioned a time or two, my very favorite Lovecraftian creations. I’m not actually hugely picky about how they’re portrayed. All I require of the cone-shaped, body-snatching keepers of the Archives is that they be awesome, creepy as hell, and trying to save the world. Caine takes some serious liberties with the original version, but keeps that core that gives “Shadow Out of Time” its power.

Part of that core is the combination of inhuman aloofness with almost inconceivably high stakes. We were talking a couple of weeks ago, yet again, about the difficulty of selling human sacrifice in a cosmic horror context. For the most part, either you’re hungry for mortal hearts on an altar, or you have motivations beyond human comprehension. If Cthulhu just wants to eat you, what really separates him from a killer tomato? The Yith transcend this type of pedestrian sacrifice. Lovecraft’s version won’t even kill you, only steal a few years and destroy your personal and professional life. Why? Oh, just to preserve the history of the planet. Caine’s Yith are willing to actually kill you—and make you pretty miserable on the way—to better serve that ultimate goal of preservation.

And then give you a bonus Kafkaesque afterlife, because they’re nice like that. I love that the Yith here are good, in their own way, in spite of how horrific and repulsive they are to humans. And unlike Lovecraft’s critters, they can sympathise with humanity in shared mortality. They’re not jumping forward to inhabit the beetles en masse, rebuilding the Great Library in a safely post-elder-thing world, but planting seeds in a garden they won’t get to see.

Perhaps that desire for continued legacy, as much as any feeling of quid pro quo, is why they toss Rose’s mind forward. There’s a nightmare-fuel-snuffing fanfic to be written after the story ends, about her calming down and getting accustomed to life among the beetle people. I would read that.

Right, let’s talk about Rose. Rose, who gives a whole new meaning to being an elder care technician. Rose, who with the absolute one-foot-in-front-of-the-other laugh-so-you-don’t-cry pragmatism required for nursing home work, is as far from a traditional Lovecraft narrator as you can get. Unlike Peaslee, she doesn’t run from Yithian ephipanies. Even terrified. Even while making/being made the ultimate sacrifice. She chooses, as much as she can when backed into a corner by an inherently terror-inducing telepath.

Starting off in a nursing home is also an interesting choice—again, not a setting Lovecraft would have been comfortable writing. It’s interesting, isn’t it, that in spite of the endless references to madness, he never wrote a scene in one of Arkham’s asylums, or anything like one. I don’t blame him for not wanting to cut that close to home. But Caine does, and gets it right, from the black humor and secret pride of the caregivers to the achingly clear-eyed descriptions of the patients. (I never held that job—I don’t have the physical or emotional stamina. But my wife put me through grad school doing nursing home medical transport. Ask her some time about the woman who thought she was Bill Clinton, and how/why to say “Let go of me” in Spanish.)

For all we worry about existential threats like climate change and nuclear war and the rise of the elder gods, Alzheimer’s is the most cosmically horrible thing most of us are likely to face directly. Piece by piece, forgetting the things that make you human. At least the Yith replace you, or your loved ones, with something. With them around, there’s a purpose to the loss.

There’s a case to be made, sometimes, that cosmic horror is actually pretty darned optimistic.

Next week, “Cement Surroundings” provides a taste of Brian Lumley’s longer underground adventures. You can read it in the Haggopian and Other Stories collection—or if you’re fortunate in your book collection, in August Derleth’s Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos anthology.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.